Over the last three months, undergraduate students Joelle Cutting and Charlotte Lovell have been working on a volunteering project here at Special Collections to create dissertation guides for students interested in using archives and rare books. The guides aim to highlight under-used archival collections and encourage more students to the breadth of resources held here in the Special Collections. This blog will introduce you to the project and explore some of the highlights of each guide.

You can find the dissertation guides on the Special Collections LibGuides webpage.

Knowing where to start with your dissertation is an incredibly daunting task, but we hope that the English and History Dissertation guides that we have been working on over the past few months will help. These dissertation guides were created in collaboration with staff from the University’s Special Collections to help students access some of the excellent material in our archives here at Exeter.

Joelle:

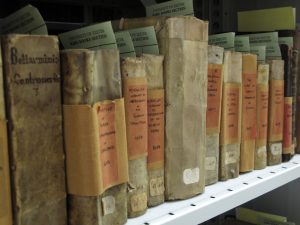

After combing through the online archival catalogue, we have organised collections into categories that cover possible avenues of interest for dissertation topics. For example, in the English Dissertation Guide there is a section that lists all the archives relating to writers from the Southwest. We have an exceptional collection of unique material here at Exeter, and these dissertation guides provide a great starting point for research. It is worth noting that for those doing a creative writing dissertation, or doing a joint honours course that includes a language, there are opportunities discussed in the guide too. Some of the collections offer inspiration for a creative writing dissertation and others are written in other languages, providing the chance for translation. Plenty of the collections have had very little research done about them and provide plenty of scope for a unique and original dissertation topic.

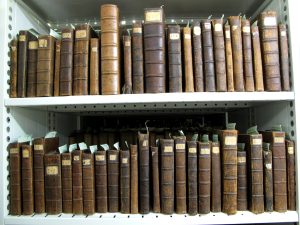

Within the guides, there is introductory information on how to use the guides themselves and how to navigate the online archival catalogue which holds information about all of the archives in our Special Collections. The physical archival material discussed in the guide is kept in the Old Library and can be viewed by booking an appointment on the Special Collections website — the guide contains further details on how to do this.

Charlotte and I have learnt so much about the collections during this project, so we thought we would share some highlights from the collections that we found particularly interesting.

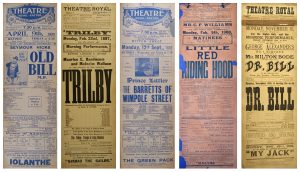

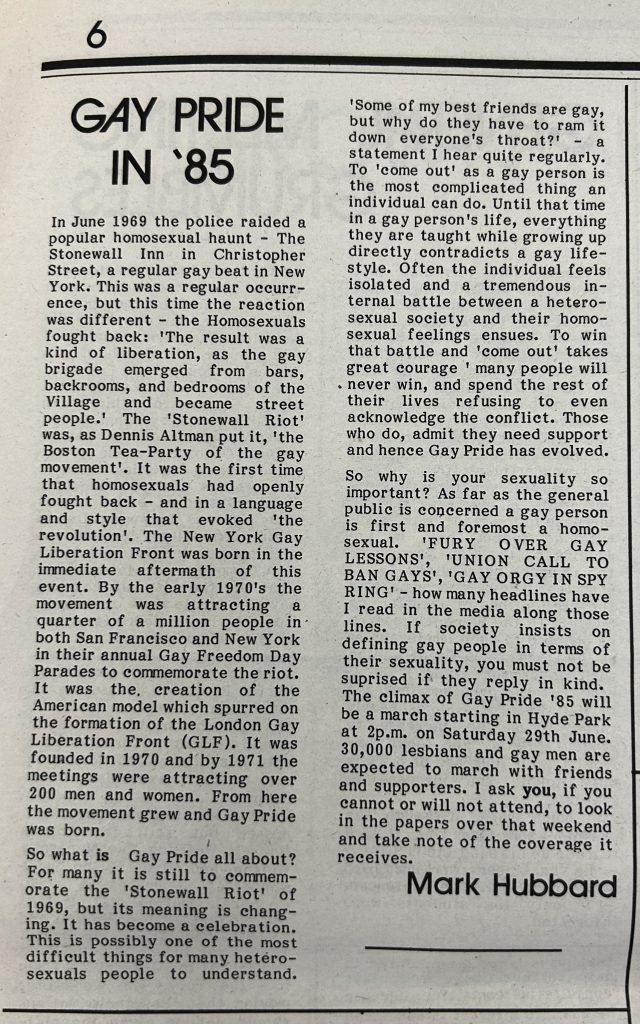

The English Dissertation Guide includes topics such as well-known writers, poetry, theatre, and journalism, but also features more niche topics that you may not have considered. One of the elements of the archival material that we have here at Exeter which surprised me was the amount of biographical writing. After studying the genre of life writing more closely on the Transatlantic Literary Relations module in second year, I was made aware of how this genre of writing has been often overlooked. I think that the wealth of biographical material we have in our archives could inspire an interesting exploration of the life writing genre and its importance.

Another topic in this guide that particularly excited me was the Art and Literature section. Art and literature are both creative outputs that influence culture and oftentimes influence each other. In our collections here at Exeter we have material relating to the collaboration between poet Ted Hughes and artist Leonard Baskin which might prove to be of particular interest to those who studied Modernism and Modernity in their second year. Aside from these two examples there is a real wealth of material to explore in the Special Collections, so if you’re feeling stuck with your dissertation, I really do encourage you to go and have a look for yourself!

Charlotte:

I hope that the history dissertation guide will be helpful, as one of the biggest hurdles when writing any piece of history is locating relevant and reliable primary sources. This guide is organised into thematic categories ranging from politics and government, military and scientific history to religious/folk, education or women’s history and so much more. Each category is then organised into three general period distinctions of medieval, early modern and modern, to make navigation and discovery optimal. Obviously, categorisation is not this clear cut, and it is worth looking through categories you might not be immediately drawn to as these sources will have a plethora of uses not necessarily restricted to the more obvious categories. It is for this reason that the guide will often signpost the collections that can be used very clearly in multiple collections.

The guide intends to highlight underused collections in a way that also encourages creative and interdisciplinary approaches. To do this, each section concludes with a few ideas for how the guides can be used, including comparative methods of research. This was one of my favourite parts of creating the guide. As my degree is only three years, and as there is only so much history one can write in that time, it was very refreshing and thought-provoking to look for ideas and themes within areas of history I wouldn’t normally get to explore. For example, I found the history of education collections fascinating, especially the Margaret Littlewood papers on Ford Manor (a school of music and physical therapy) and how they might connect to the Sue Jennings papers on dramatherapy. Exploring these collections opened my eyes to the innovative educational methods and therapeutic practices from different historical periods, and how they intersected with broader cultural and social trends.

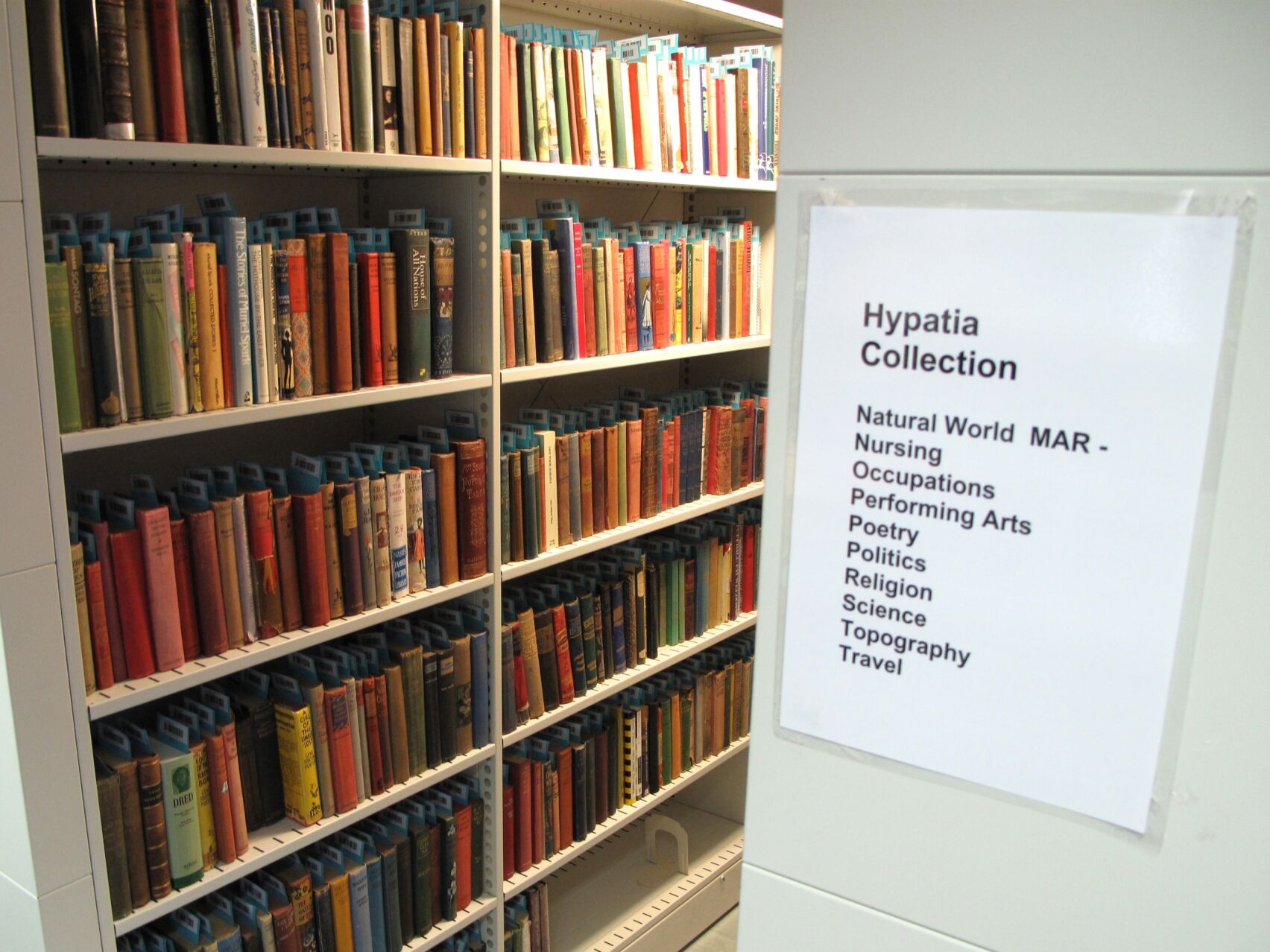

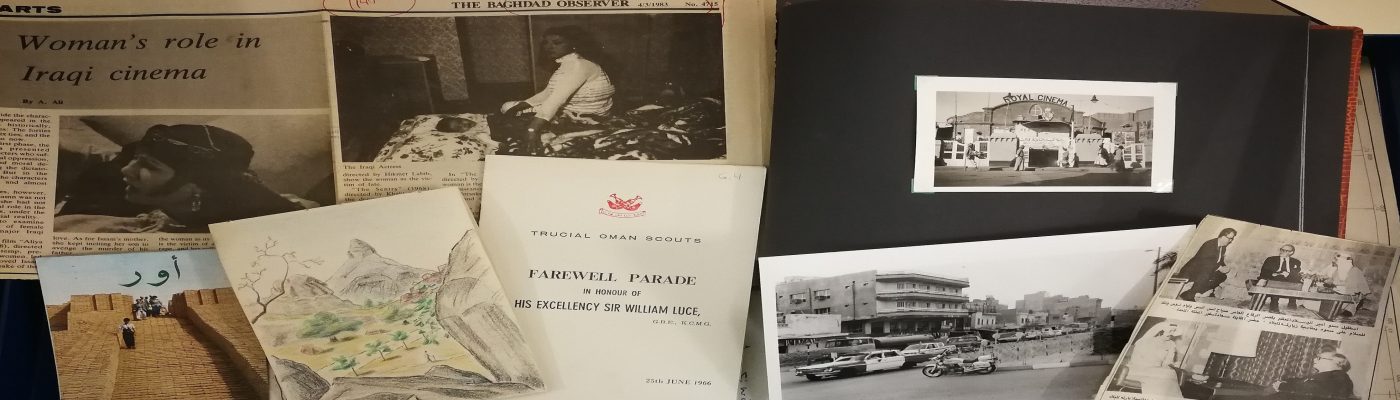

The guide also highlights some important standalone collections, like the Bill Douglas Cinema Museum and the Hypatia collection. The Bill Douglas Cinema Museum is a treasure trove for anyone interested in the history of film and cinema. It houses an extensive range of artefacts, from early cinema apparatus and memorabilia to film posters and personal papers of filmmakers. This collection is perfect for exploring the evolution of cinematic technology and the cultural impact of film through the ages.

The Hypatia collection is dedicated to literature by and about women. It’s a huge collection that covers a wide range of topics, from women’s suffrage and feminist theory to women’s contributions in various fields. This collection is invaluable for understanding the historical and ongoing struggles and achievements of women, providing rich primary sources for research on gender studies. You can find out more about the Hypatia collection on the Special Collections’ LibGuides.

Something that cannot be understated is the wealth of resources available at the University’s archives. This project took over 12 weeks and still will only be able to scratch the surface of the research opportunities available in the University’s archives. I highly encourage, at any part of your degree, to have a look at the guide and begin to think about how the University’s collection can be utilised in your work. And, most importantly, going into the collection and seeing some of the incredible archives you have access to while at the University of Exeter.

in 1987.

in 1987.

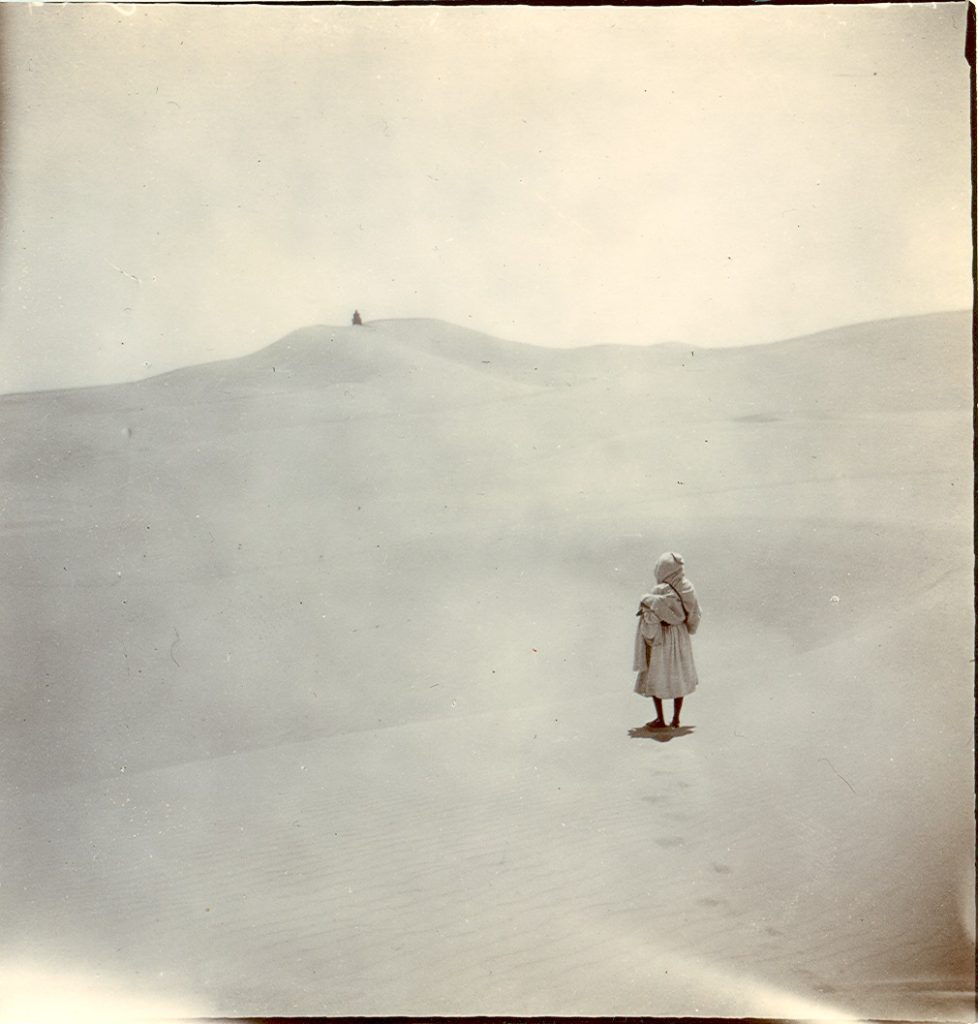

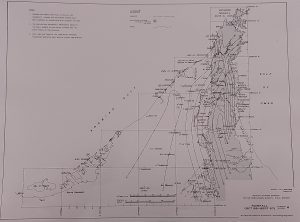

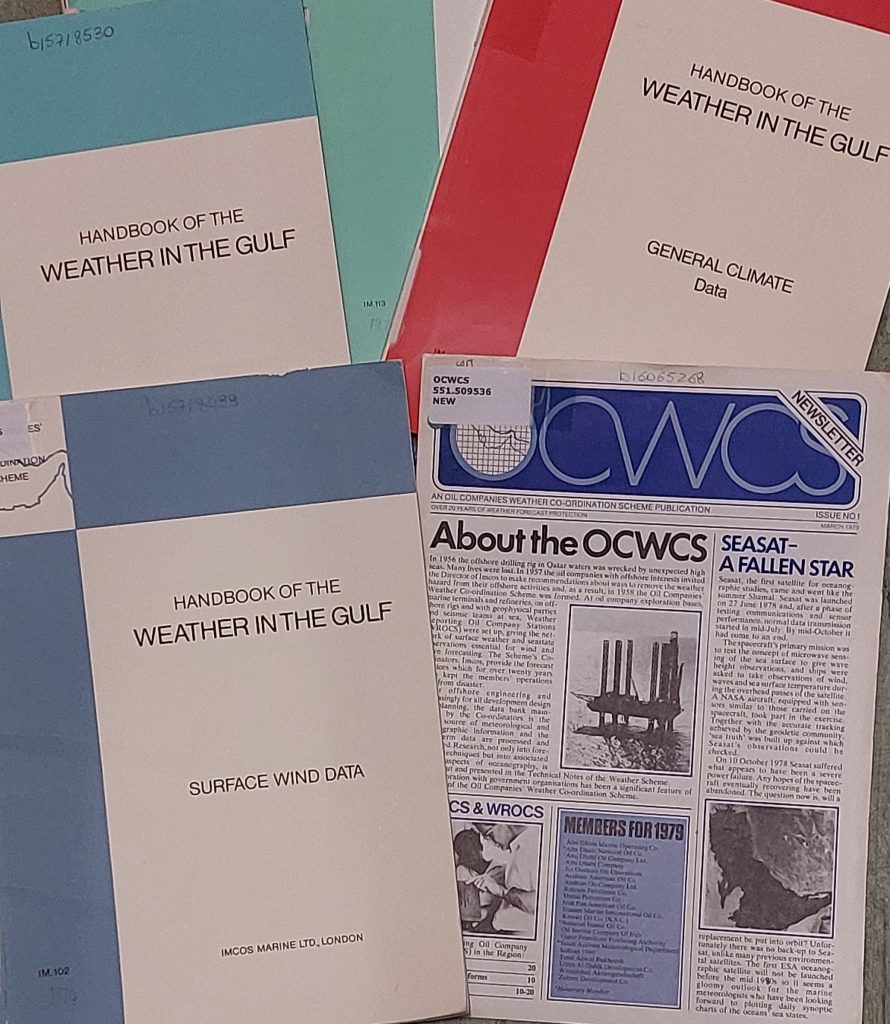

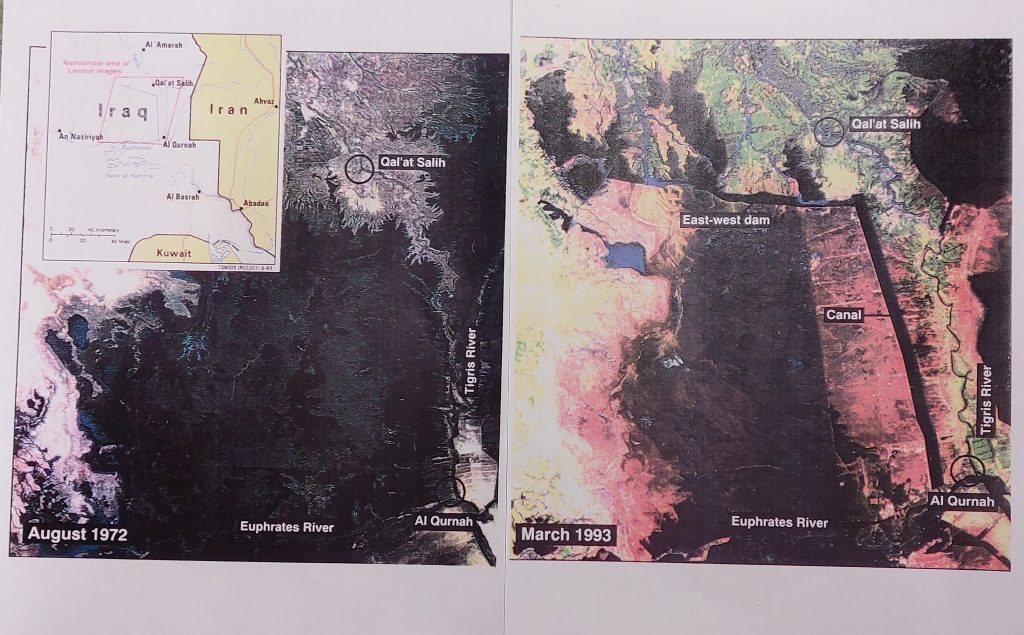

This year marks the 30th anniversary of the opening of the Channel Tunnel and Special Collections is pleased to announce a new exhibition relating to investigations and studies in the 1950s-1960s for a channel crossing. The display case is located on Level 1 of the Forum Library, near the entrance from the staircase. This exhibition has been created by Special Collections staff with the assistance of student volunteer Vanessa Wong and features items from the papers of the civil engineer Sir Harold Harding, including reports, publications, articles and photographs.

This year marks the 30th anniversary of the opening of the Channel Tunnel and Special Collections is pleased to announce a new exhibition relating to investigations and studies in the 1950s-1960s for a channel crossing. The display case is located on Level 1 of the Forum Library, near the entrance from the staircase. This exhibition has been created by Special Collections staff with the assistance of student volunteer Vanessa Wong and features items from the papers of the civil engineer Sir Harold Harding, including reports, publications, articles and photographs.