As this week is Student Volunteering Week, we are celebrating our amazing student volunteers: Charlie, Ted, Esme and Mitch!

Volunteers make an invaluable contribution towards Special Collections, enabling us to extend the work that can be done by our team, and making our collections more accessible for people to use and enjoy. Volunteering is unpaid, but can offer a wide range of benefits to those who generously volunteer their time with us, including the opportunity to get hands-on with unique collections, to develop new skills and knowledge, and to gain valuable experience which can improve employability.

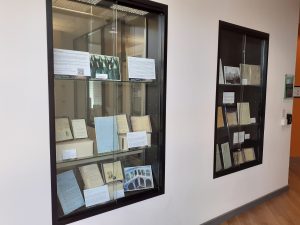

For the academic year 2024-2025, Special Collections has been delighted to welcome four student volunteers to our team: two Exhibitions Volunteers and two Collections Care Volunteers. The Exhibitions Volunteers have been working with a member of Special Collections staff to plan and co-curate an exhibition of Special Collections materials. The Collections Care Volunteers have been working with a member of Special Collections staff to repackage archive materials into new housing suitable for long-term preservation.

Charlie, Ted, Esme and Mitch have kindly agreed to share some of their experiences of volunteering with Special Collections below. The Special Collections team would like to take this opportunity to thank them for their fantastic work, enthusiasm and dedication.

Charlie (Exhibitions Volunteer)

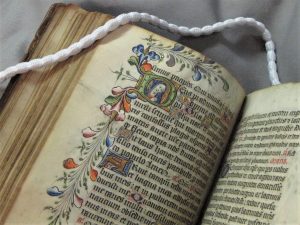

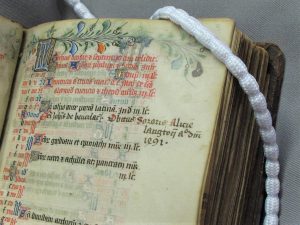

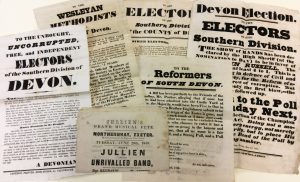

Since October, I have been fortunate enough to work as an Exhibitions Volunteer with the University’s Special Collections. The role involved many happy afternoons sifting through archival materials in the Ronald Duncan Reading Room, selecting several to display and discuss in an upcoming exhibition on magic and law in the Forum Library. The Special Collections house a number of extraordinarily significant items relating to the history of magic, including a personal favourite; a 1588 copy of the Malleus Maleficarum (Baring-Gould Library 0495), a foundational text for the witch-hunt craze in Europe and North America. Copied 102 years after its initial publication, the worn binding bears witness to the respect afforded to the text – and, therefore, is a sharp reminder of the devastating consequences of its contents. Indeed, engaging with the material aspects of manuscripts and learning what this communicates about the owner, the environment, or the cultural significance of the object and others like it has been my favourite experience. It makes history tangible, so learning how to handle archival material has been invaluable. It has also been exciting to use one manuscript to learn about another, connecting the dots between the available items to create a complete historical picture to present. The Malleus, for example, can somehow be mentioned alongside a pamphlet concerning the Bideford witch trials, almost 400 years its junior! In short, creating an exhibition for the Special Collections has been great fun and a massive privilege, and I’m excited to present my findings.

Ted (Exhibitions Volunteer):

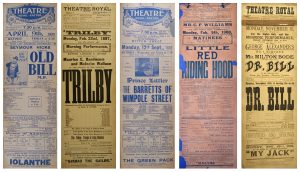

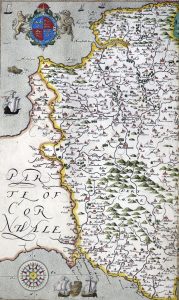

As a Special Collections Exhibitions Volunteer, I am currently creating an exhibition regarding the life of Jack Clemo (1916-1994), utilising the archives’ considerable collection of: letters and diaries, as well as deeply sentimental objects such as love letters and dog fluff. A religious poet, Clemo remains highly praised for visionary writing on mysticism that was noted for its visceral realism. Set within the backdrop of Cornwall’s clay mining pits, Clemo invoked a “clear, fiery vision” and was referred to by A.L. Rowse as the “progeny… of Thomas Hardy”. This realism and clarity of vision are even more remarkable when considering that Clemo was completely deaf and blind for the vast majority of his adult life; although he was quick to point out that he became blind after the release of his early works. Exploring the Clemo archive within Special Collections offers a remarkable insight into the life of a firebrand poet with a fierce spiritual vision, who was able to write with grounded realism even after his senses had been lost.

Esme (Collections Care Volunteer):

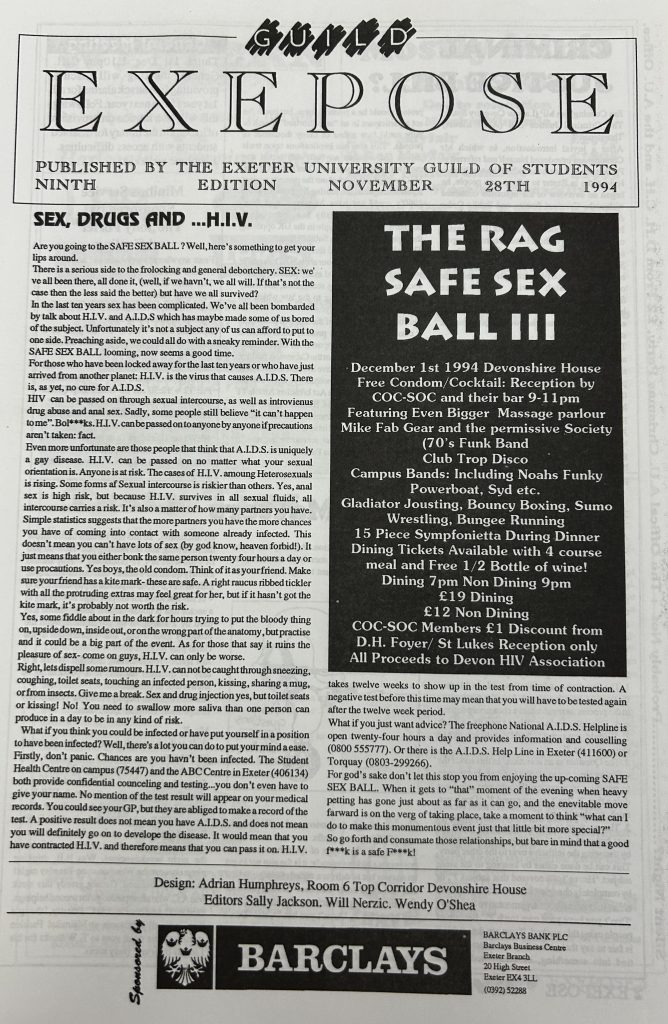

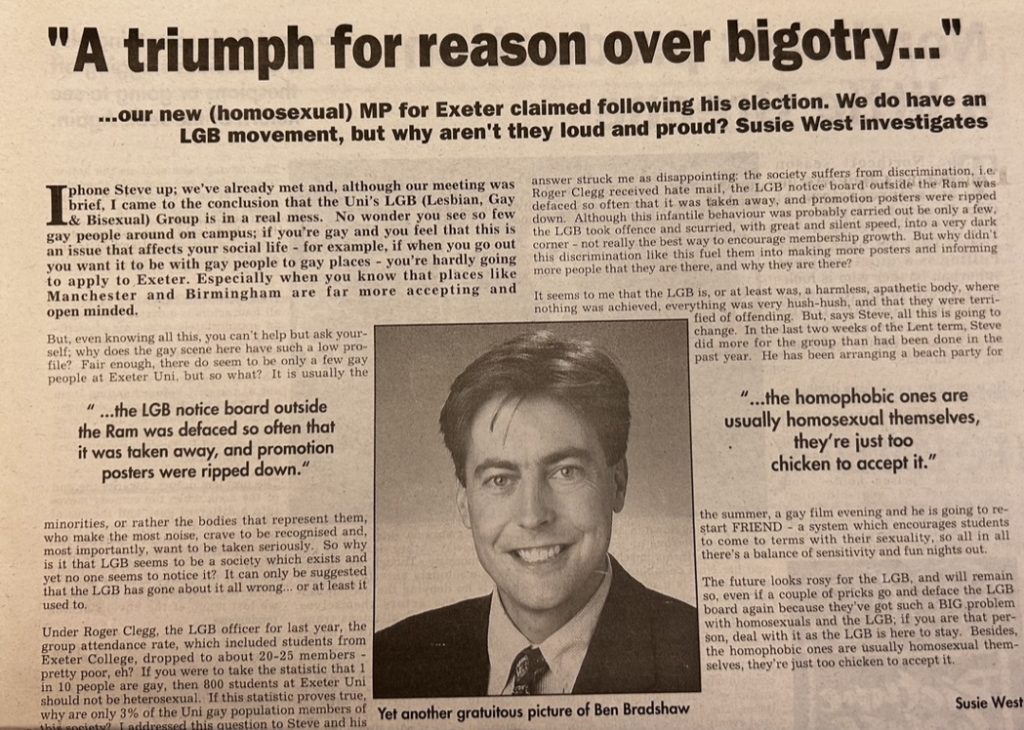

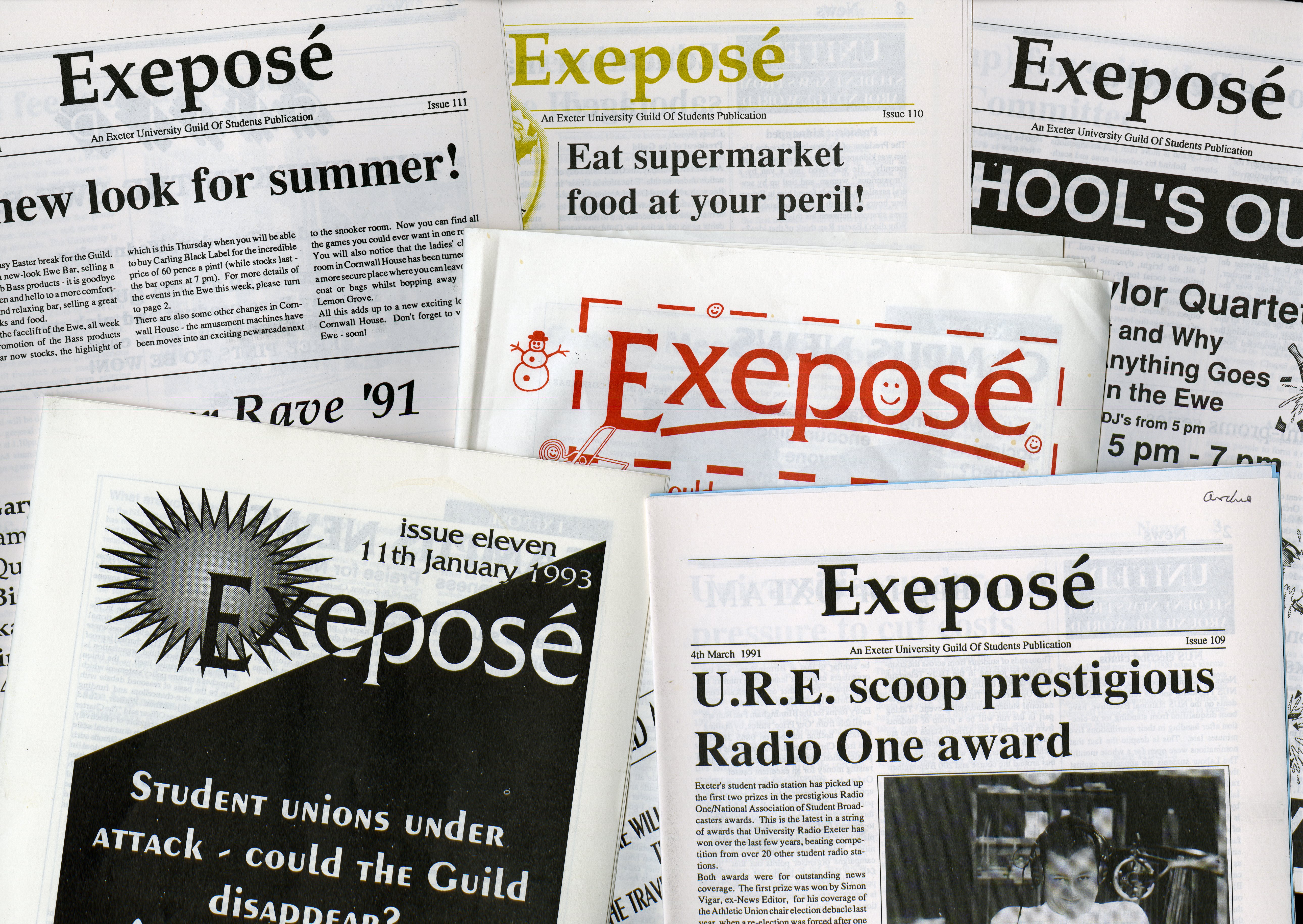

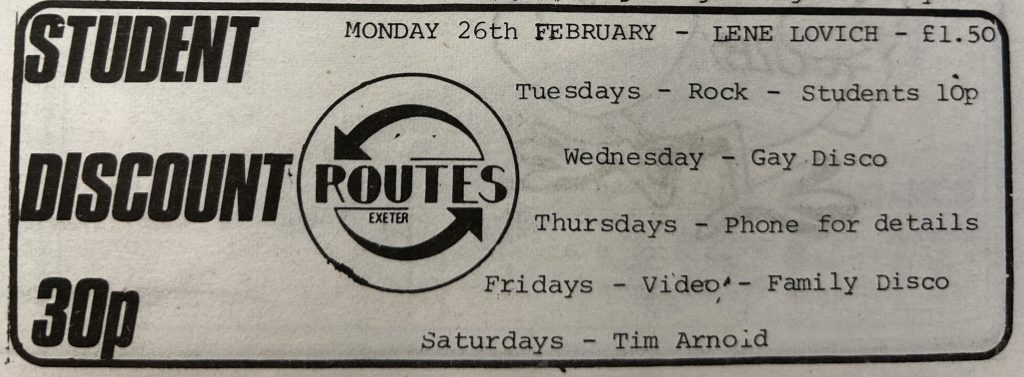

I have loved my experience working as a Collections Care volunteer at the university’s Special Collections. This role has given me a great opportunity to see behind-the-scenes of how an archive operates and the intricacies of managing rare and unique materials. One project I have particularly enjoyed was cleaning and repackaging Alfred William Clapham’s postcard collection, which contained over 2300 postcards of notable landmarks and buildings across Britain. In the process of repackaging, I was also able to read correspondence from as early as 1903, and I enjoyed the detective work of finding the locations of landmarks that Clapham hadn’t been able to locate pre-internet. I was also able to help with the catalogue information for this collection, improving accuracy through counting the postcards and noting dates where they were available. My most recent project has been listing items that were recently collected from the St Luke’s Library, and it has been fascinating to read student periodicals from the 1970s-1990s and gauge their opinions on student life. These items will join the University Archive.

Working in the archives has also allowed me to explore other materials for my own interests, such as Francis James Child’s collection of English and Scottish Ballads, which I enjoyed writing a blog post about. I have also been able to make use of archive resources for my degree, and viewing primary sources in the Special Collections has been invaluable to extending my understanding of material and print cultures and the importance of archives. I would thoroughly recommend volunteering in the Special Collections to anyone interested in these materials, as you get to work with a lovely group of people and gain knowledge about so many different aspects of the work that goes into maintaining these resources.

Mitch (Collections Care Volunteer):

It’s not often that you can approach the curtain of your university programme and peek behind the fabric of journals, articles, and academic excess. The production of knowledge can seem so glossy that you might forget that it must come from somewhere, with brilliant people working tirelessly to categorise, organise, and research the raw materials required for its shine. The University of Exeter’s Special Collections team gave me just that opportunity, and I doubt I’ll ever look at my set-readings in quite the same way.

I applied for the volunteering position because I wanted experience. What experience, exactly? Well, I didn’t quite mind. When studying in the Humanities, job prospects are always in doubt, and so hands get grabby when it comes to opportunities. Of course, I expected the volunteering would give me some experience in archiving, but I hardly knew what that meant. An archive recalls arcane, moss-covered temples with devout robe-wearing scholars meticulously sorting a mine of knowledge, and I’ve largely found that despite a notable lack of moss and robes, that’s not altogether false!

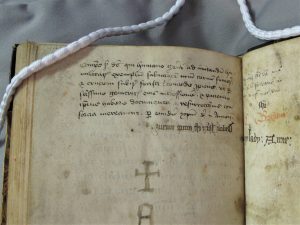

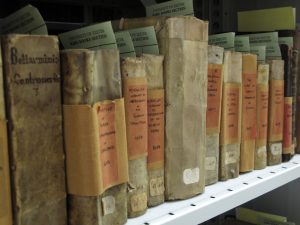

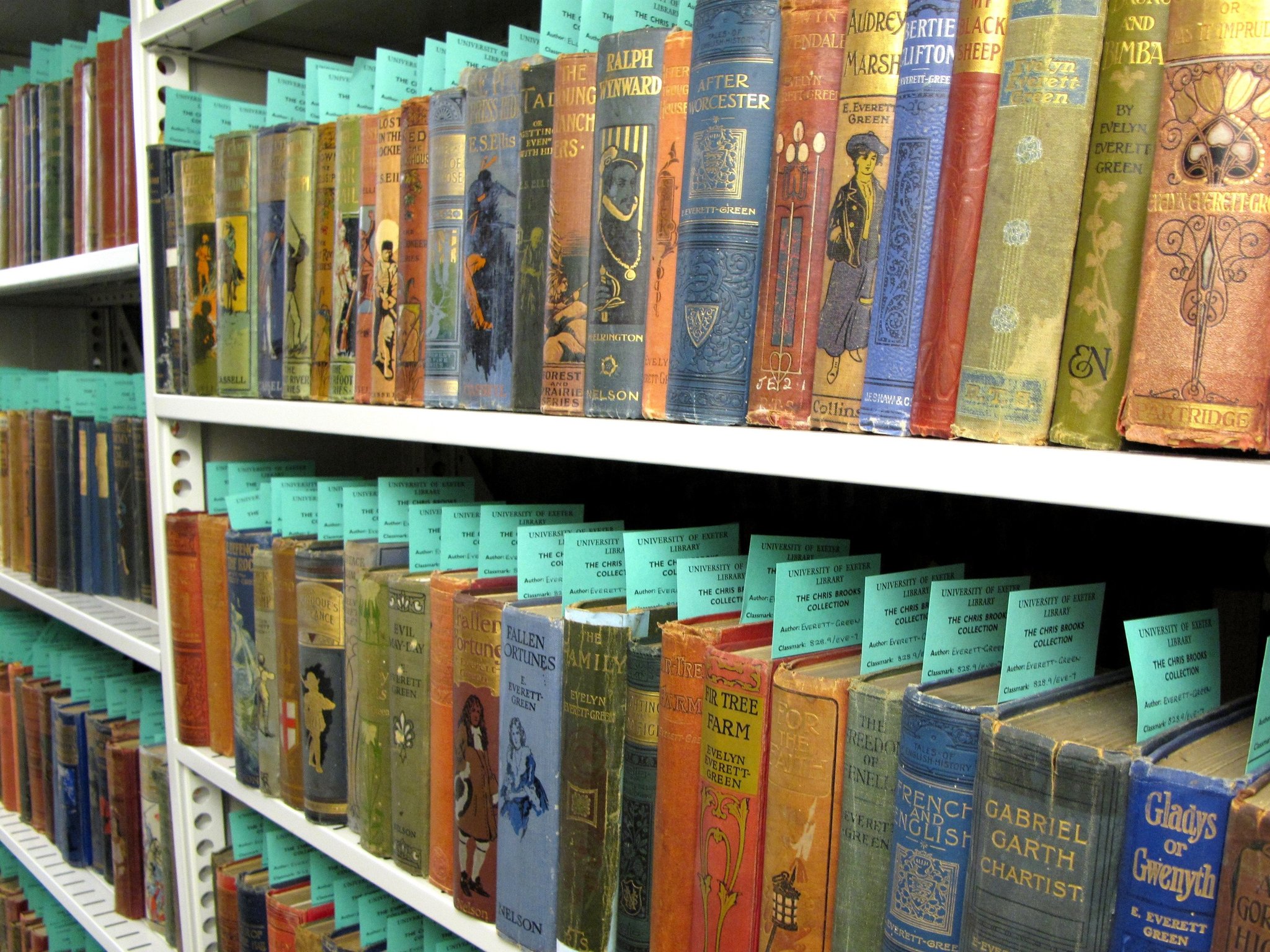

My time with Special Collections has been spent growing familiar with the archive’s wealth of facilities, resources, and rituals. Under the supervision of James, I have developed the skills to handle a range of manuscripts and rare books, repackaging them, and marking them up for storage. My time with James has involved working on the Middle East Collections, becoming not only familiar with the processes of handling and repackaging, but the collection itself. Every step of the way, James talked me through the contexts of manuscripts, and the lives of their predecessors, working to break the sterility of work through an engagement with the cultural artefacts as they passed through my hands.

The Jean Trevor archive has been one of particular interest for me. The opportunity to understand her documents through the context of her life and legacy, and all the while gaining access to her research on rural Nigerian populations and their lived experiences, has been intellectually enriching. Her connection to the University of Exeter was especially attractive, inviting the sense that I was engaging in a localised academic community, albeit in a small way. It has been a pleasure to repackage and sort her notes and research.

Finally, I would recommend the volunteering programme to anyone looking to enrich their engagement with the academy and knowledge studies. The Special Collections archive offers their volunteers the opportunity to see knowledge-production in action, while gaining valuable skills in handling and repackaging fascinating material. Not only that, but I believe the work has clarified potential career choices for me and birthed a wealth of new perspectives on the Culture and Heritage sector. Thank you to both Annie and James for your ongoing support.

Special Collections runs a small volunteering programme, which currently accepts up to four volunteers for time-limited projects (usually three to six months). The volunteering programme is open to university students and staff, as well as members of the public. New volunteering opportunities in Special Collections are advertised at the beginning of the Autumn Term (see University term dates), with any additional spaces being advertised as they become available. Find out more on our Volunteering webpage.

in 1987.

in 1987.