Written by Chloe Cicely Chandler (MA English Literature)

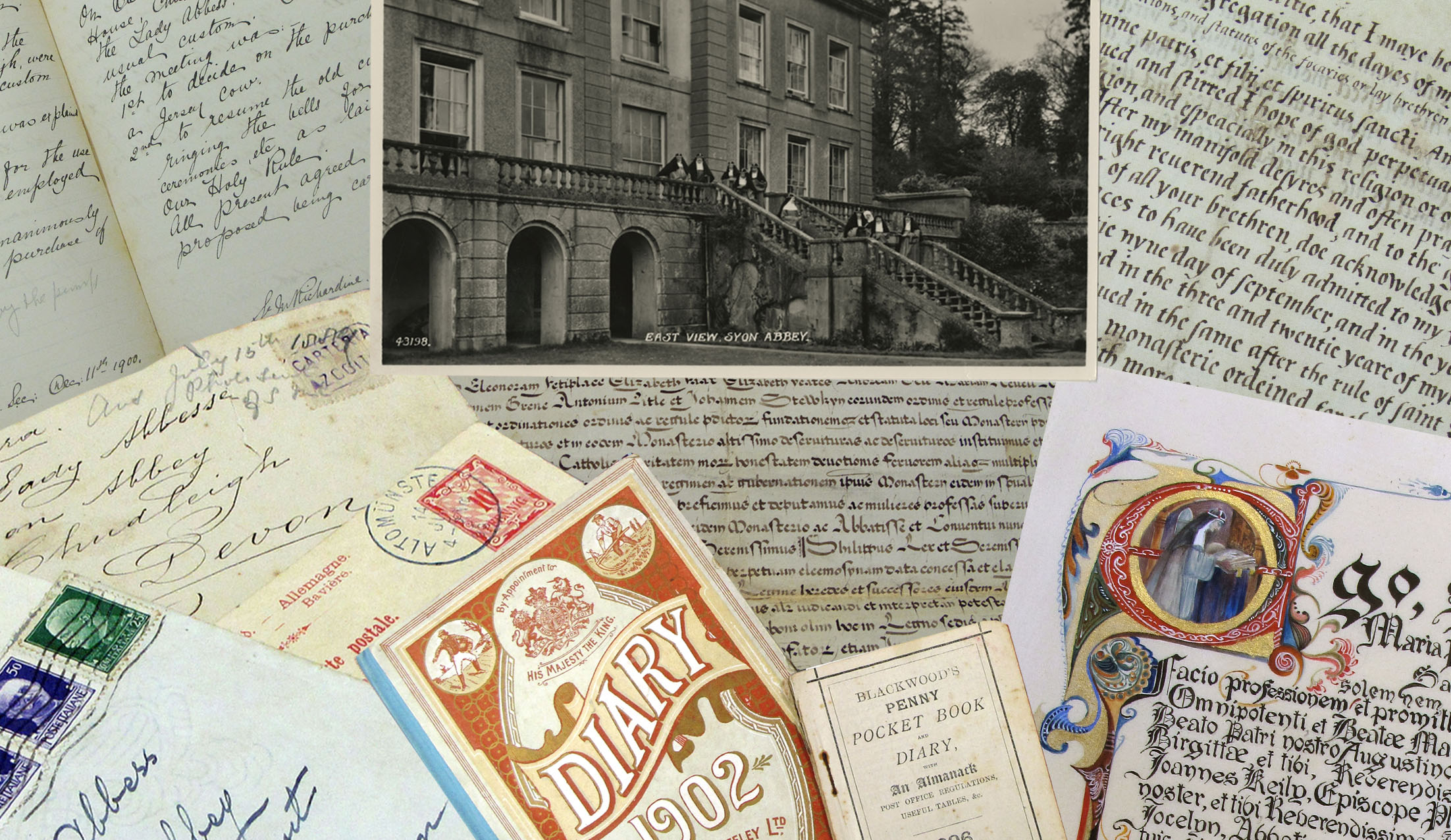

In March of 2019 I somehow found myself within the British Library’s Manuscripts Reading Room with my eyes delighting over the sprawling handwriting within Coleridge’s notebooks. Ever an inspirer of wonder in me, it was magical to see his mind come alive; the thoughts seeming to burst onto the page with frantic imagination. I was especially fixated by Coleridge’s sketches of the Lake District that recorded the walks he had adventured on with his fellow Romantic visionaries: William and Dorothy Wordsworth. I often reflect on the fact that I touched the paper upon which Coleridge had scribed over 200 years ago. Now, it seems as if it were a distant, hazy dream. This was the first ever encounter I had with physical archival research, and one I would never forget. The research was undertaken during my English undergraduate degree for my third-year dissertation on altered states of consciousness in Romantic literature. In addition to Coleridge, I also focused on the writings of Sir Humphry Davy and Thomas De Quincey. This led me to take a separate journey where I also travelled to the Morrab Library in Penzance to learn more about Davy’s poetical and chemical experimentations from the archives in his Cornish hometown.

Both of these experiences were incredibly rewarding and put into perspective what I most enjoyed about studying English literature: that ability to peer into history through the words that individuals have left behind; as if the gap in time between the past and the present has been momentarily suspended. Such opportunities for research were the highlight of my entire degree – they made me feel more connected to the research I was conducting, and encouraged me throughout the difficult process of writing and editing my dissertation – providing my work with a greater sense of purpose.

Out of these explorations, I became very interested in the ways in which I could make the most of being an English MA student at a research-focused university and partake in opportunities to delve into the archives. This academic year, I joined as one of the Library Champions for English. As part of this role, I act as a liaison between library staff and students, passing along feedback, suggestions, and making book requests on behalf of students within my subject area. I had the opportunity to develop a project of my choosing relating to library services. Consequently, I decided it would be valuable to concentrate my project on the Special Collections based at the University of Exeter. Specifically, I wanted to consider the ways in which students could be made more aware of the unique primary resources available to them in order to increase their engagement with the archives during their degree.

Surveying Student Feedback

It was important for me to first gather insight from my fellow peers, so I put together a survey that was open to students from across the disciplines. This survey aimed to get a sense of general student knowledge of the archival services that the university offers, whilst also offering a space to make suggestions for how the Special Collections could be more integrated into the student experience. Although the responses ended up being mainly from Humanities students – with a majority from English undergraduates – their experiential highlights and suggestions were immensely helpful in terms of evaluating the current dialogue between students and the Special Collections.

Of those who had used the archives, their memories were very positive. One student relayed their enthusiasm as such: “I have only accessed the archives as part of a workshop on accessing them and it was really interesting! [The] Staff [were] great and very informative, I will definitely be in touch if there is something I need to access.” Speaking of the online catalogue, a student mentioned how valuable it was for their research: “I loved it, I accessed it almost daily to complete my assignments.” Others recall their use of the archives as: “[an] Intriguing and … exciting experience”; additionally: “I found the archivist very helpful and friendly and enjoyed the experience.”

The main areas that could improve student engagement with the Special Collections, as suggested by those surveyed, related to the following:

– Accessibility: student responses highlighted how the process can appear daunting, whilst other students were less aware of where to begin researching.

– Visibility: students highlighted a need to increase overall awareness of the collections through visual displays and marketing throughout the university. As a fellow student expressed: “I’d love for more people to handle and see these manuscripts.”

Following this initial feedback collection from my student cohort, I wanted to get a more informed perspective of the process behind performing archival research: this required me to find archival works of interest from the catalogue and then arrange a viewing of them.

The Process

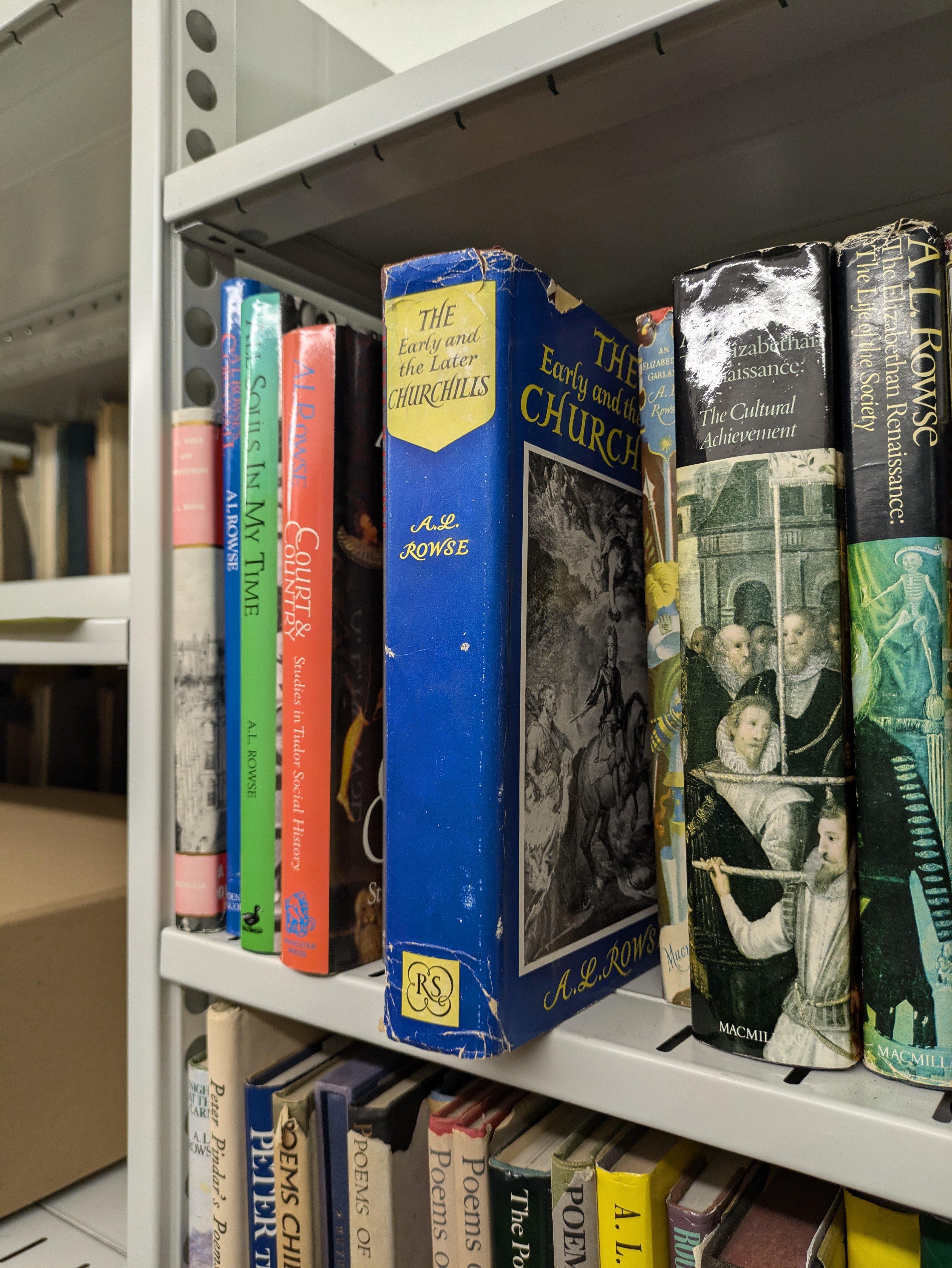

As a starting place, the Collection Highlights page is especially helpful as it presents intriguing items within the university’s collection which you can then search for on the Archives catalogue, or use as a springboard for other research ideas. My personal interests for my MA dissertation relate to Romantic and Gothic literature of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. I am also interested in kindred areas such as the supernatural and folkloric. From our discussions, the Special Collections team gave me some fantastic suggestions to consider based on these research topics.

Of particular interest to me was the Theo Brown Collection that comes with its own helpful collection guide. Brown was a renowned folklore researcher and Research Fellow within the Philosophy and History Departments at the University of Exeter. Her immense research collection has been in the university’s archive since her death in 1993. Brown had a particular focus on folklore rooted in the South West of England, and, as an individual born and raised here, this sparked my interest. From within the vast collection, I needed to specify particular items, each of which is given a name relating to the overarching topics they contain. I finally decided upon the boxes that covered ‘Fringe Lore and UFOs’, ‘Guising and Hobby Horse’, and ‘Devon and West Country witches and witchcraft’. In addition, there was a fascinating object under the Rare books and maps section that I felt compelled to see as a Gothic researcher: a 1st issue, 1st edition of Bram Stoker’s legendary Gothic novel Dracula from 1897 housed within the Lloyd Collection. This edition is renowned for its strikingly coloured cover. As one of my favourite literary works, I was delighted to hear that the university had such an item available for viewing.

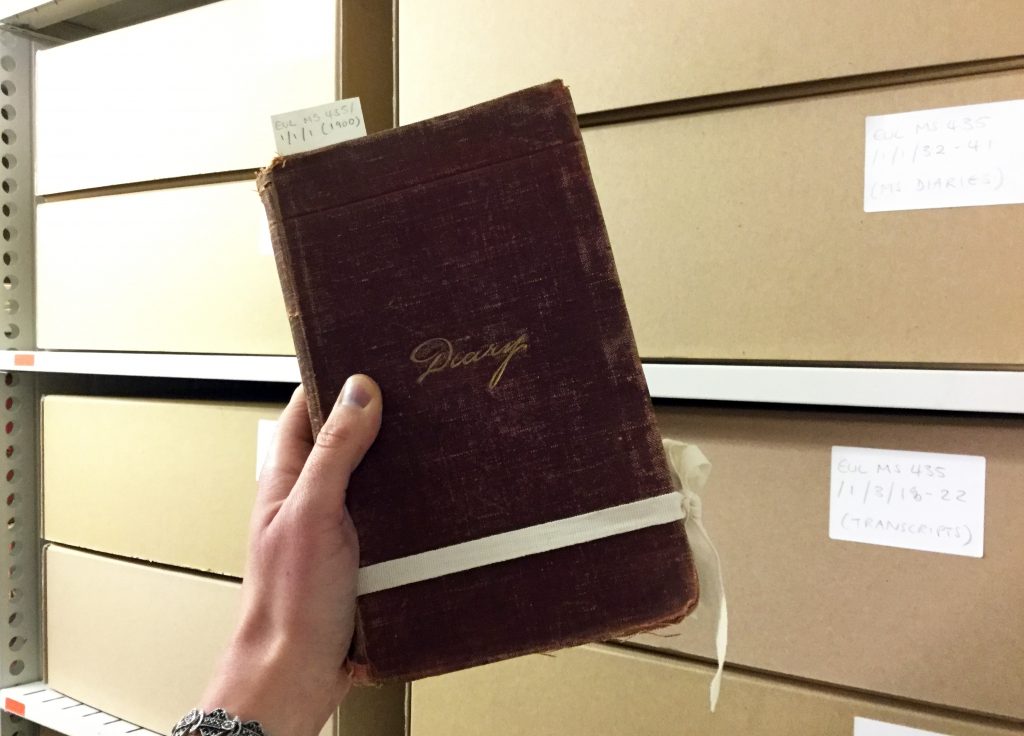

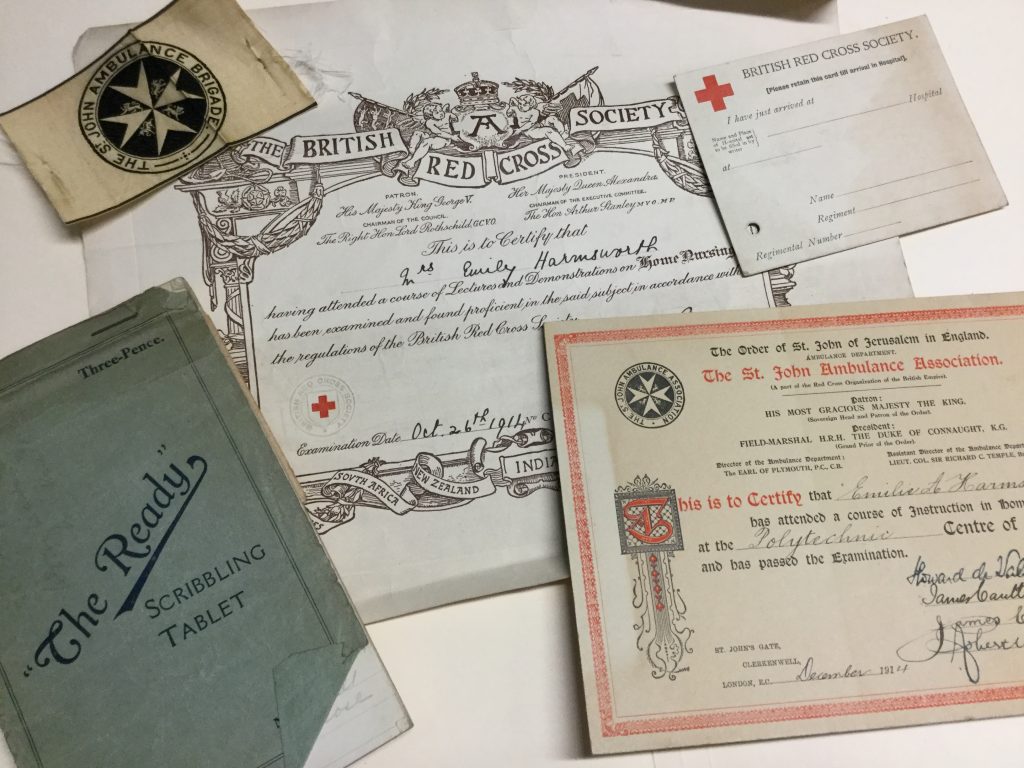

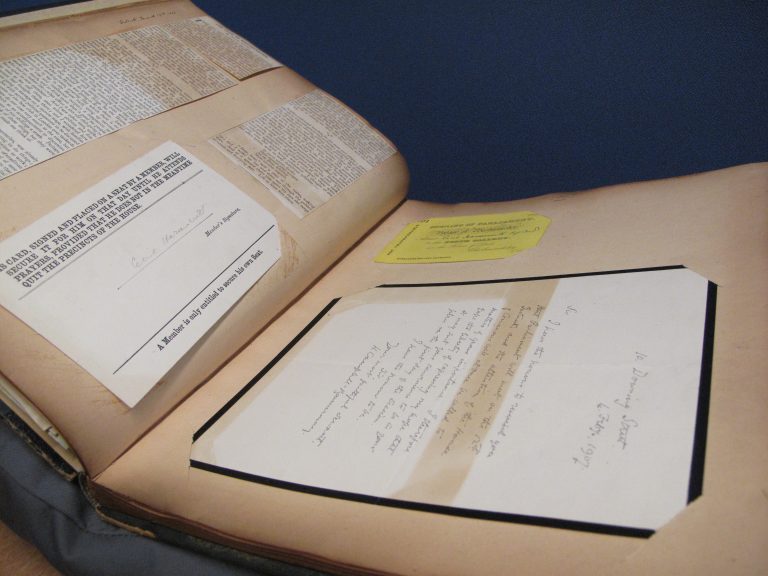

When I went about making my request via the Visiting Heritage Collections webpage, I first had to find the necessary codes for the Collections, which you can search for on the archive database: archival works have a title and MS number; books have a title and call number; journals have a title and volume/issue number. After making my request, I received an email promptly confirming my reading room booking. Before attending my booking, I read up on the handling procedures laid out in the Special Collections handling guide which provided some really useful information about how different types of materials are to be treated. This was practically helpful when I was searching through Brown’s archive as it included an array of different materials, including many pictures, for which I needed gloves. One interesting piece of information which often surprises people is that, in most cases, when handling rare books, it is preferable for you to not wear gloves as this decreases your physical sensitivity to the material itself, making it more likely that you might damage it.

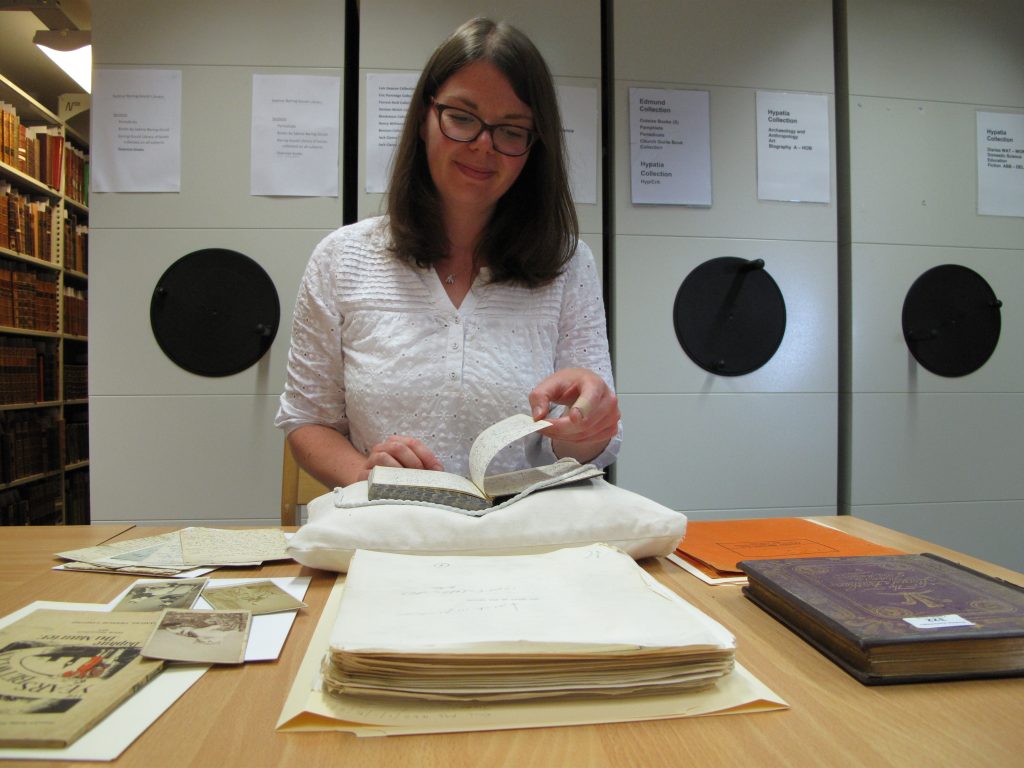

When I arrived at the Old Library on the day, I went over to the Special Collections desk to inform of my arrival. My selected items had already been prepared behind the desk for viewing and were promptly brought out. The items displayed within the Ronald Duncan Reading Room itself were instantly engaging. To one side was a writing desk that had belonged to the much-beloved author Daphne Du Maurier, which came as a wonderful surprise as I was able to sit near it whilst I researched. I had seen one of her writing desks only once before at the Jamaica Inn’s Smugglers Museum on Bodmin Moor. I was also particularly fond of the artworks on the back wall by the artist Leonard Baskin which depicted various birds, including a variety of crows – a favourite Gothic symbol of mine!

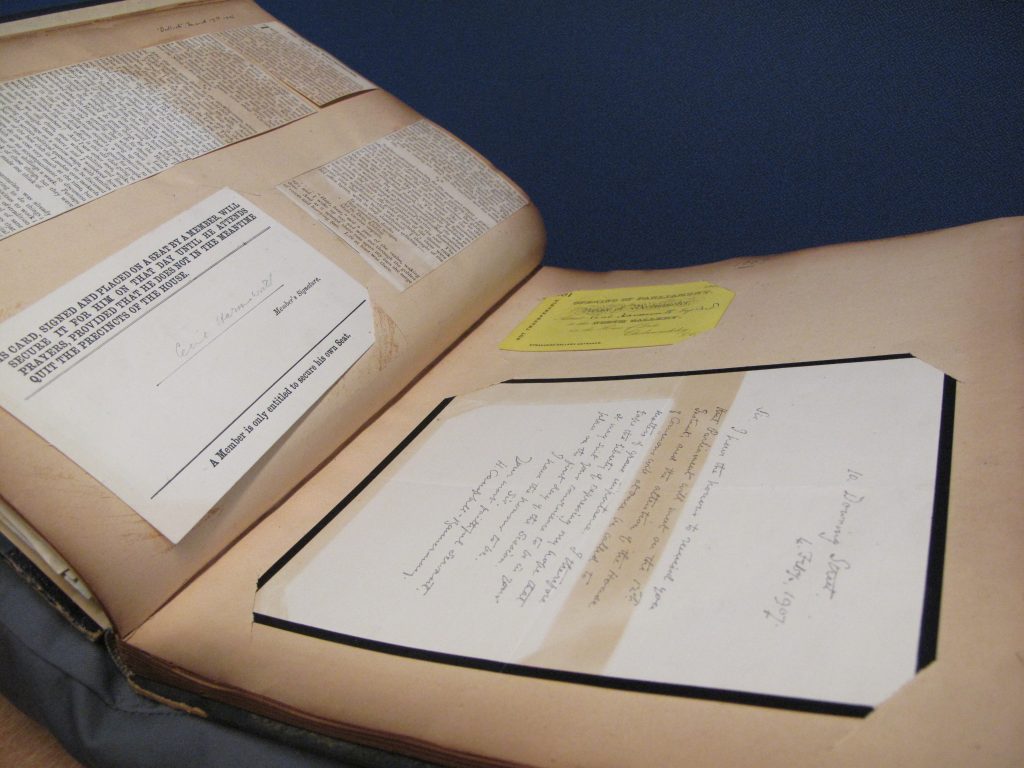

I first went about exploring Brown’s items: from memory, a news story she had collected that was immensely intriguing was about a so-called ‘witch bottle’ that had been discovered in a basement. The bottle, under examination, turned out to be filled with a concoction of items that suggested its use in a baneful, magical working, containing nails, human urine, and thorns, amongst other items. Although I had only engaged with a small part of the entire Theo Brown collection, I was amazed by how much was contained within each box and managed to spend the entire afternoon slot searching through an amalgam of pictures, newspaper clippings, and letters – how the time flew by! In light of this, I would suggest to potential Special Collection users to allow themselves ample time to view resources and not try to cram too much into one visit. Rather, take the time to enjoy researching and making notes. And, if needed, return for another visit.

Following this, I handled the 1st edition of Dracula, for which I was given a book snake weight and cushion to use, so that the spine and fragile pages would be supported. I was instantly amazed by the vivid yellow cover that adorned the book. The cover was made even more pronounced by the red lettering that spelt out the book’s title, as if written in blood; very befitting given the contents. There was something strangely modern about the book’s palette of colours that made it feel out of place for the time period in which it was written. The aesthetic choices made about the design seemed to highlight the very alluring nature of the work, presenting the book itself as a kind of fantastical object. I feel incredibly lucky to have been given the opportunity to handle these items from the Special Collection and shall remember the experience fondly.

Call For Archival Research

In recent years, I have found that research of both primary and secondary sources for assignments tends to be confined to online databases. And, although this is undeniably helpful in terms of providing greater access to works from other institutions and aiding in the search for specific terms, I find there is something inherently missing from this experience of research. When you are there in person, there is a certain magic and fascination that can be kindled, which is more difficult to attain through a digitised source. It puts you back in touch with the physical history of these sources – the feel and sensation of them – such things are often lost when searching purely within digitised collections. Whilst at university, we have the unique chance to use these resources which might otherwise be unavailable or more difficult to access were we not students.

I highly recommend my fellow students give the archives a go! You may not have a particular text or subject in mind for your research, which is completely fine; using the archives is actually a fantastic way to discover an area you might be interested in. It also incentivises you to produce more distinctly original research to present to your subject area. The archivists, with their expertise in the collection items, are also on hand to provide helpful suggestions, as they did in my case.

Future Prospects

In response to student feedback, the Special Collections team have been putting these suggestions into practice, such as, updating the website pages to make them more accessible and user-friendly. We are also planning some further collaborative projects to improve accessibility and visibility over the next academic year – so make sure to watch this space!

I would be delighted to hear from my peers: if you have any feedback or suggestions you would like to make with regards to the library services, including the Special Collections or book requests for English, please feel free to contact me at cc725@exeter.ac.uk. For more Library Champion information visit: Find your Library Champion – Library Champions – LibGuides at University of Exeter

Helpful Special Collection links

Main website: Special Collections | Special Collections | University of Exeter

Special Collection Highlights: Highlights | Special Collections | University of Exeter

LibGuides: Home – Archives and Special Collections – LibGuides at University of Exeter

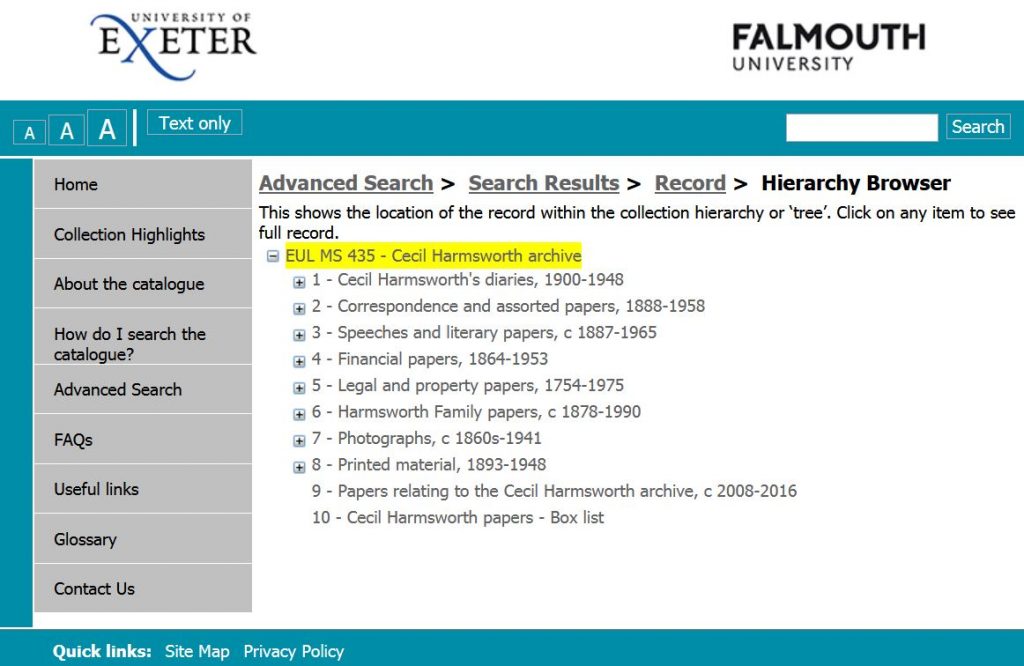

Special Collections catalogue: Home Page (ex.ac.uk)

Handling Guide: Handling Materials – Archives and Special Collections – LibGuides at University of Exeter

Bill Douglas Cinema Museum: http://www.bdcmuseum.org.uk/

Digital Collections: http://specialcollectionsarchive.exeter.ac.uk/collections/

Twitter: https://twitter.com/UoEHeritageColl

in 1987.

in 1987.

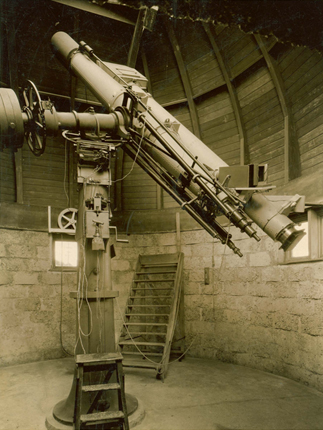

This year marks the 30th anniversary of the opening of the Channel Tunnel and Special Collections is pleased to announce a new exhibition relating to investigations and studies in the 1950s-1960s for a channel crossing. The display case is located on Level 1 of the Forum Library, near the entrance from the staircase. This exhibition has been created by Special Collections staff with the assistance of student volunteer Vanessa Wong and features items from the papers of the civil engineer Sir Harold Harding, including reports, publications, articles and photographs.

This year marks the 30th anniversary of the opening of the Channel Tunnel and Special Collections is pleased to announce a new exhibition relating to investigations and studies in the 1950s-1960s for a channel crossing. The display case is located on Level 1 of the Forum Library, near the entrance from the staircase. This exhibition has been created by Special Collections staff with the assistance of student volunteer Vanessa Wong and features items from the papers of the civil engineer Sir Harold Harding, including reports, publications, articles and photographs.