An exciting new season of cataloguing is underway here at the University of Exeter Special Collections! Three archival collections are now in the preliminary stages of being catalogued as part of the ‘21st Century Library Project’, due to be completed by July 2020. These include the Middle East Collections, the Northcott Theatre Archive, and the Common Ground Archive. In this blog post, the Common Ground Archive cataloguing project is introduced by Annie, the project archivist.

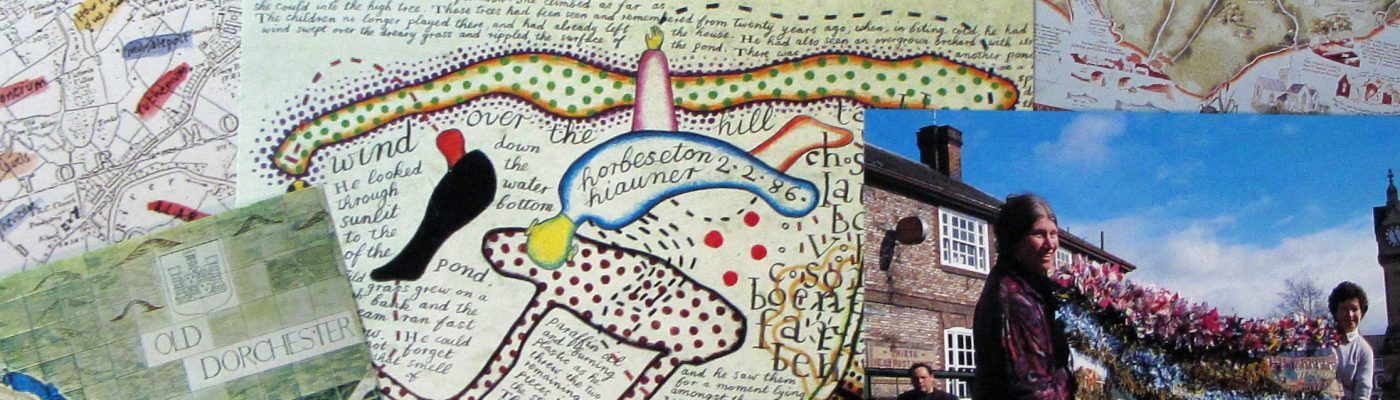

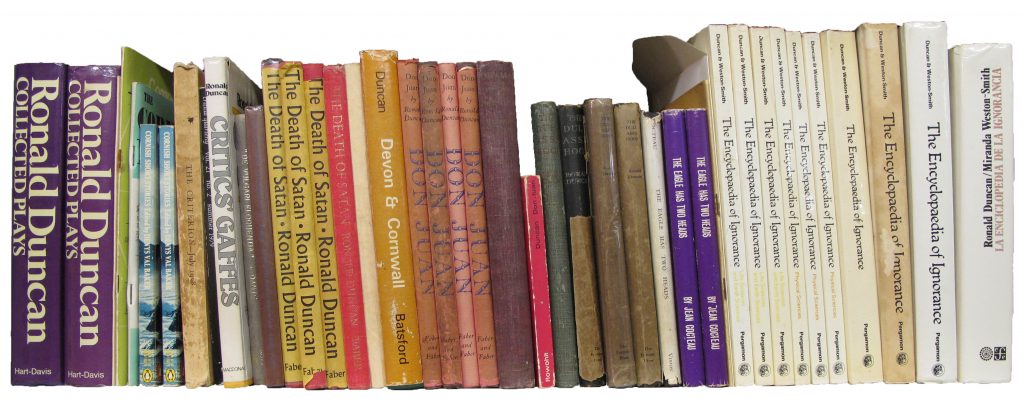

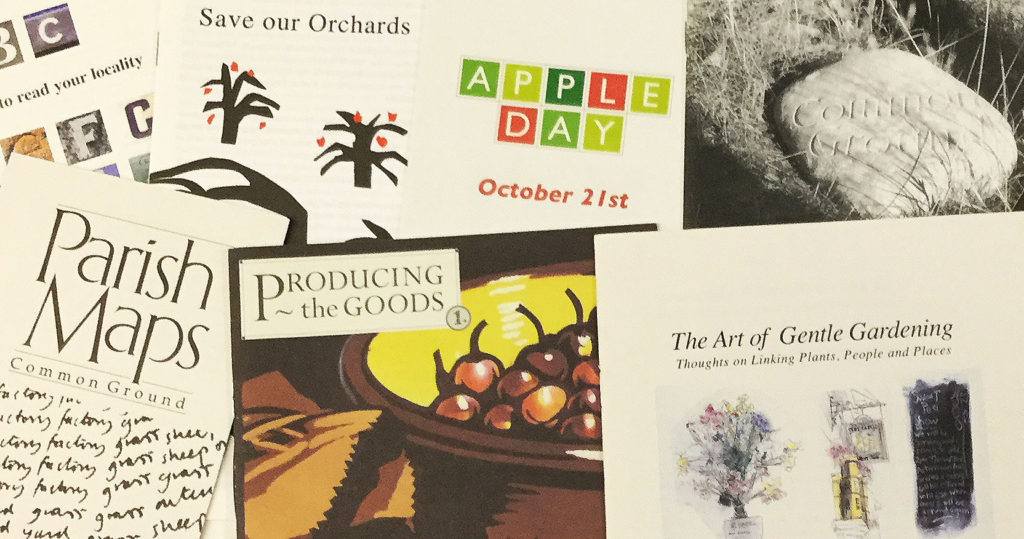

Promotional material in the archive relating to Common Ground projects

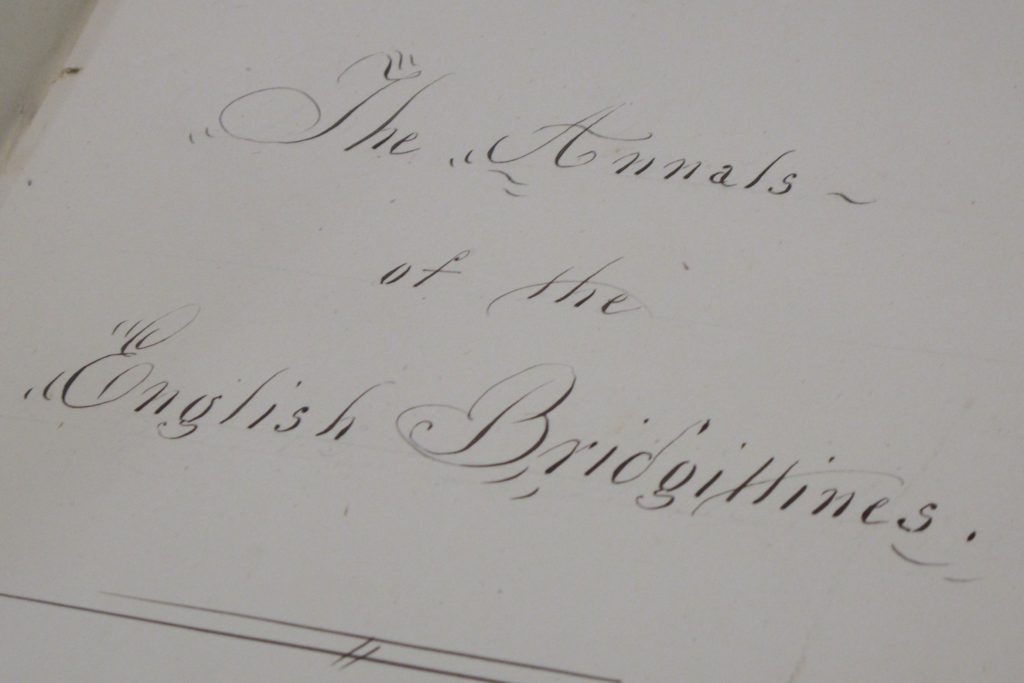

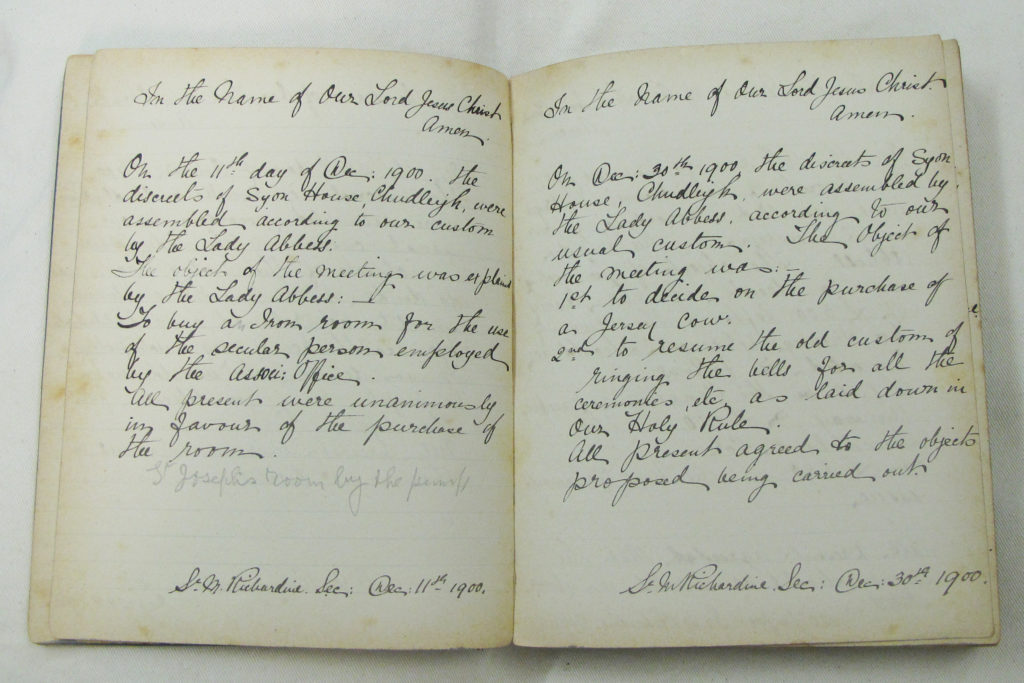

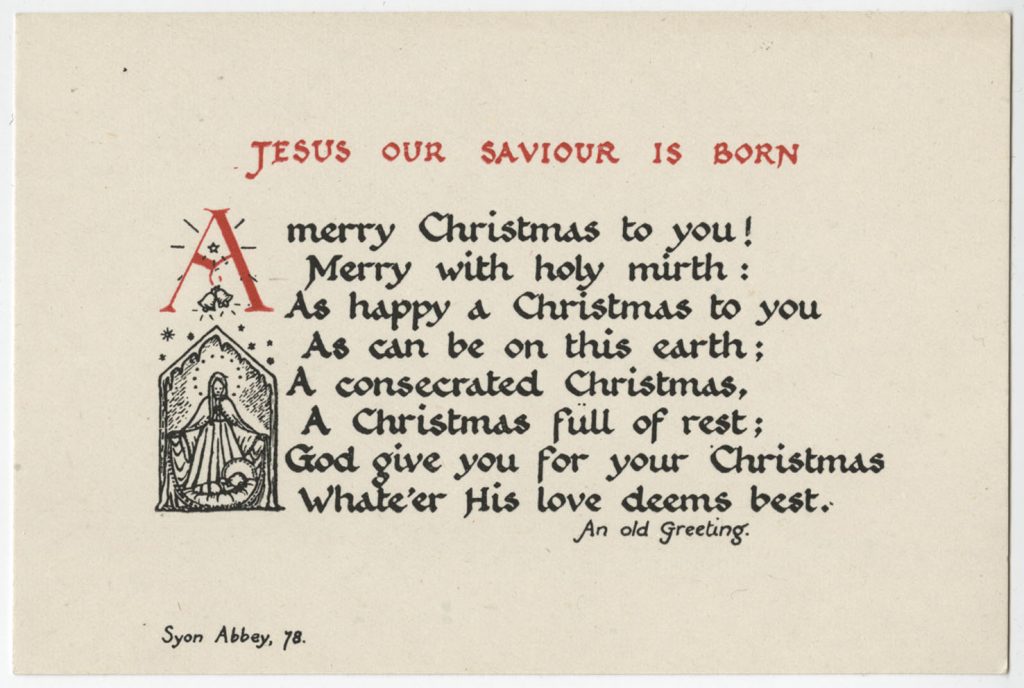

Having fondly waved goodbye to the Syon Abbey archive (now neatly organised into boxes and described in the online catalogue), in August I embarked on a new cataloguing project: to catalogue the archive of Common Ground, an arts and environmental charity (reference number EUL MS 416).

Common Ground is an arts and environmental charity that was founded in 1982 with a mission to encourage people to emotionally engage with their local environment through the arts. For over three decades, Common Ground has been collaborating with local communities, artists, writers and composers to celebrate the ordinary – and not just the extraordinary – in our localities and, in doing so, encourage conservation at a grassroots level. Projects initiated and developed by Common Ground, and which have had a considerable impact on the cultural geography of Britain, include: the Parish Maps project, the Campaign for Local Distinctiveness, and Apple Day. The output from the many projects has included artistic commissions, performances, exhibitions, conferences, and publications.

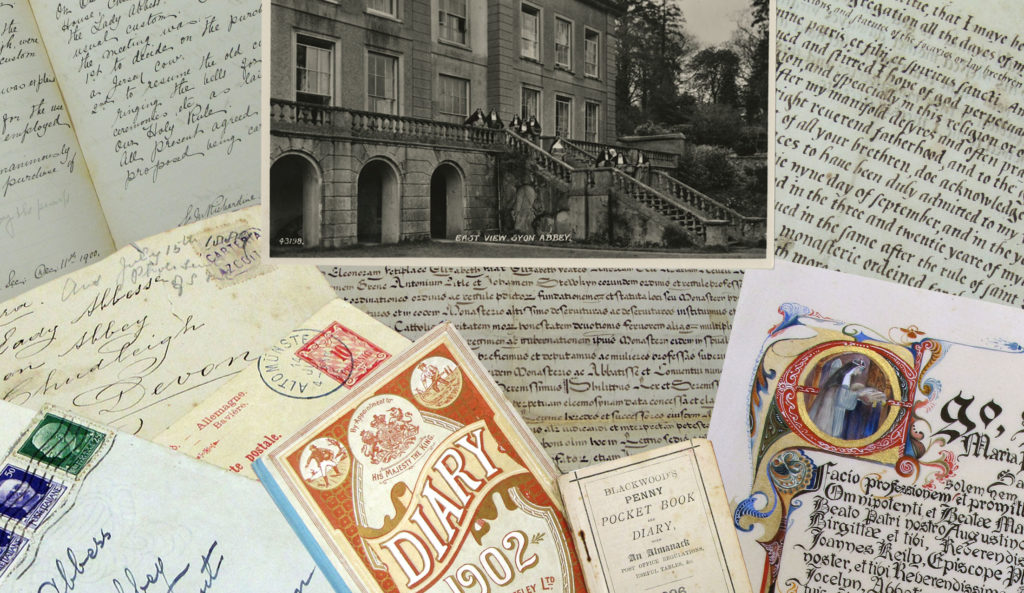

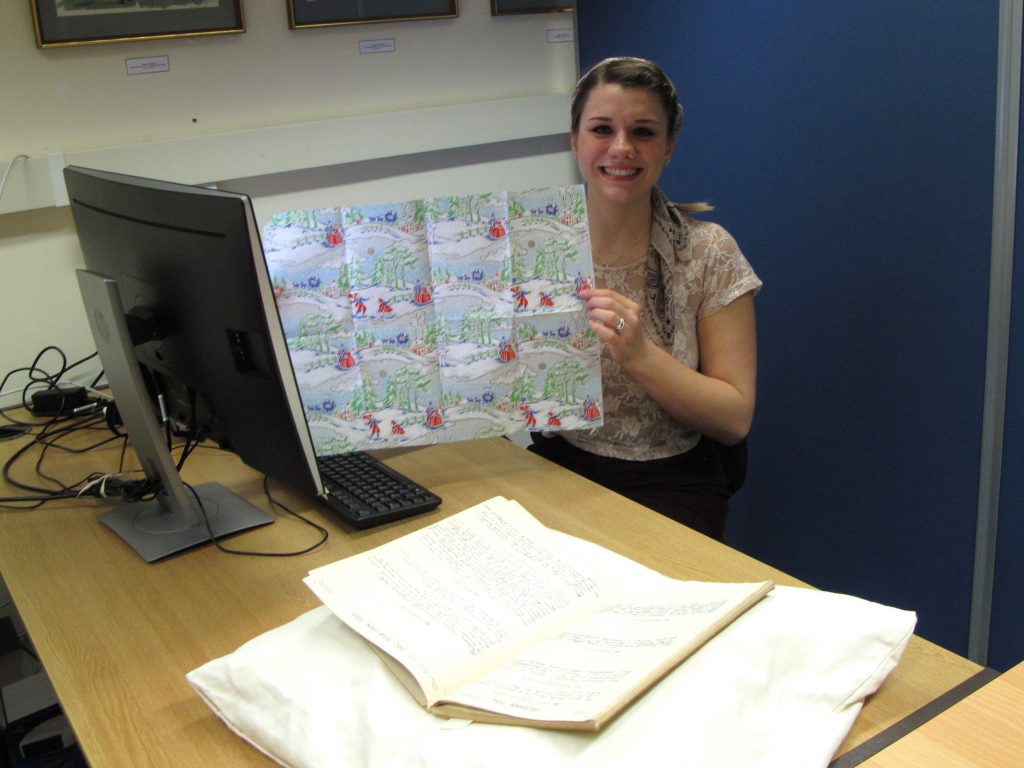

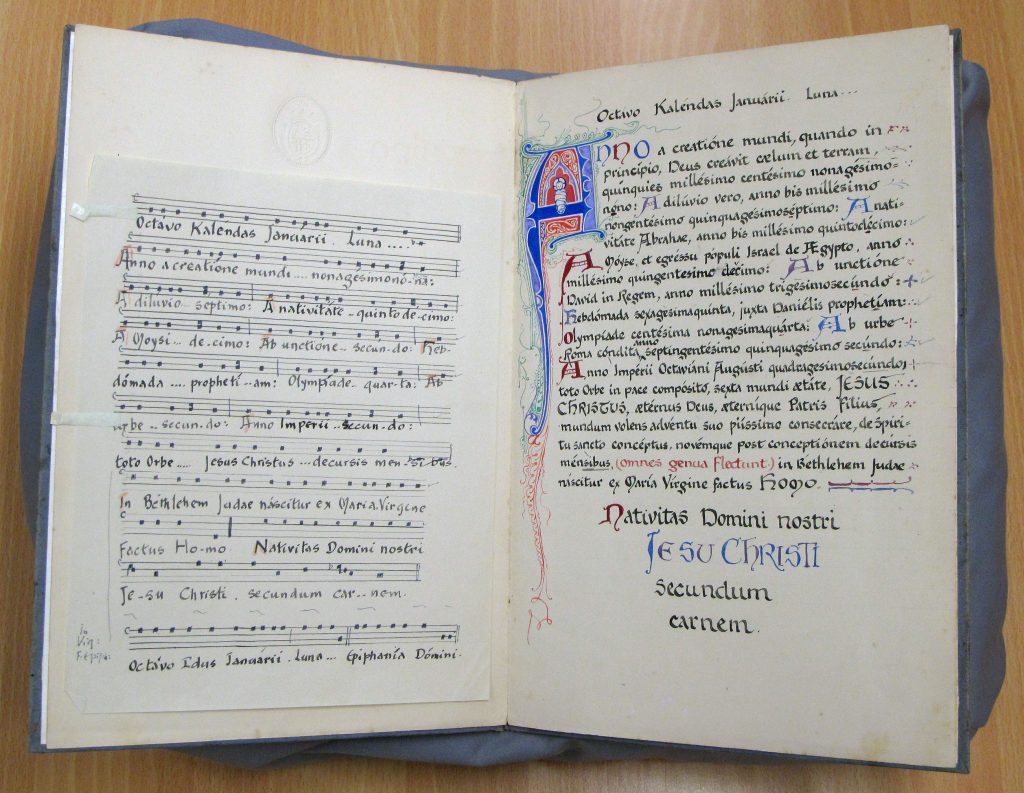

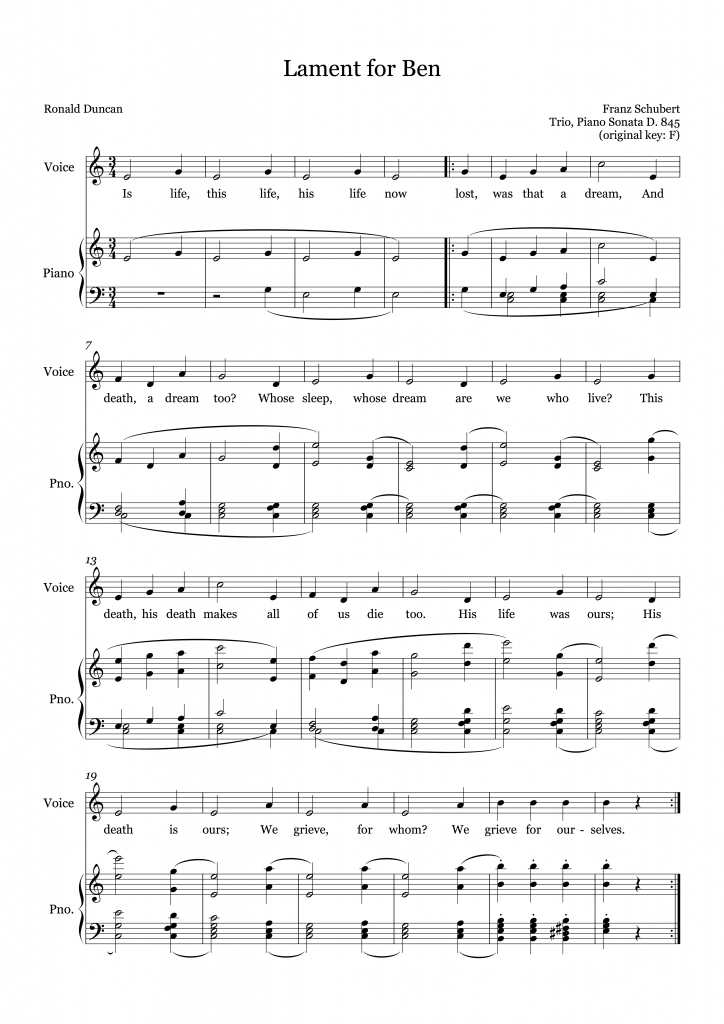

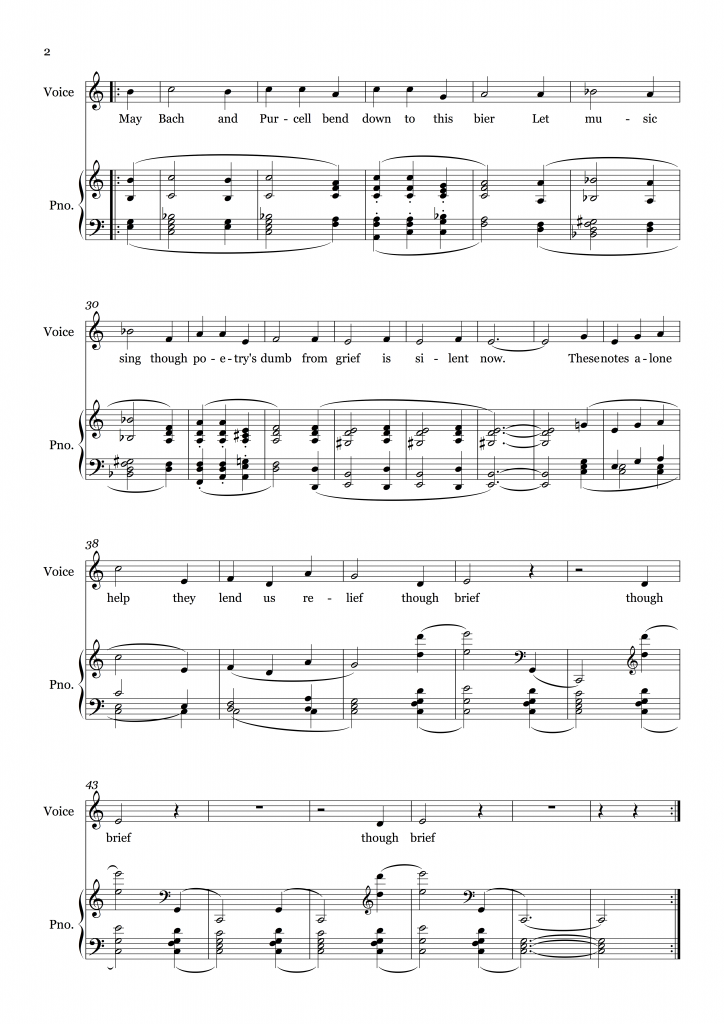

One of the aspects I most enjoy about being an archivist is the opportunity to learn something new and develop expertise in the most unexpected areas. Every archive offers new knowledge as well as new challenges, and I knew the Common Ground archive would be no exception. Over the past month I have been conducting a survey of the archive to gain an understanding of how it was used and organised by Common Ground, and to identify any potential issues. The archive comprises a range of material, from correspondence, notes, financial papers, reports, press clippings, and research material, to photographs, audio recordings, sheet music, publications, and promotional material (which even includes t-shirts and tote bags!). The archive also contains some different types of media such as cassette tapes, CD-ROMs, VHS tapes, and floppy disks. Dealing with these different formats and making them accessible for use now and in the future will be a new and very different kind of challenge to those I faced on my last project, but one that I am looking forward to tackling.

Box files in the Common Ground archive

The Common Ground archive has rich potential for interdisciplinary research on geography, literature, visual arts, sustainability, sense of place, the relationship between nature and culture, and the British landscape and culture. Although the archive is already roughly organised according to the various projects, over the next two years, considerable sorting, repackaging, and basic preservation will be required to ensure the records are in the best condition possible for long-term access. In addition, the archive will be described at least down to file level, and will be searchable via our online archive catalogue. And as with my last project, I look forward to sharing highlights from the archive and keeping you updated on my progress via this blog and our Twitter account.

I hope you’ll join me again soon!

By Annie, Project Archivist