In the last two blogs, we have looked at what the Omar Sheikhmous archive (EUL MS 403) holds in relation to the activities of both the KDP and the PUK, discussing the collection as an archival record of Omar Sheikhmous’ life and work. In this third blog, we will be looking at the archive within the wider context of Kurdish studies and possible ways in which the Sheikhmous papers might be studied and used.

Part 3: The Omar Sheikhmous archive (EUL MS 403) and Kurdish Studies

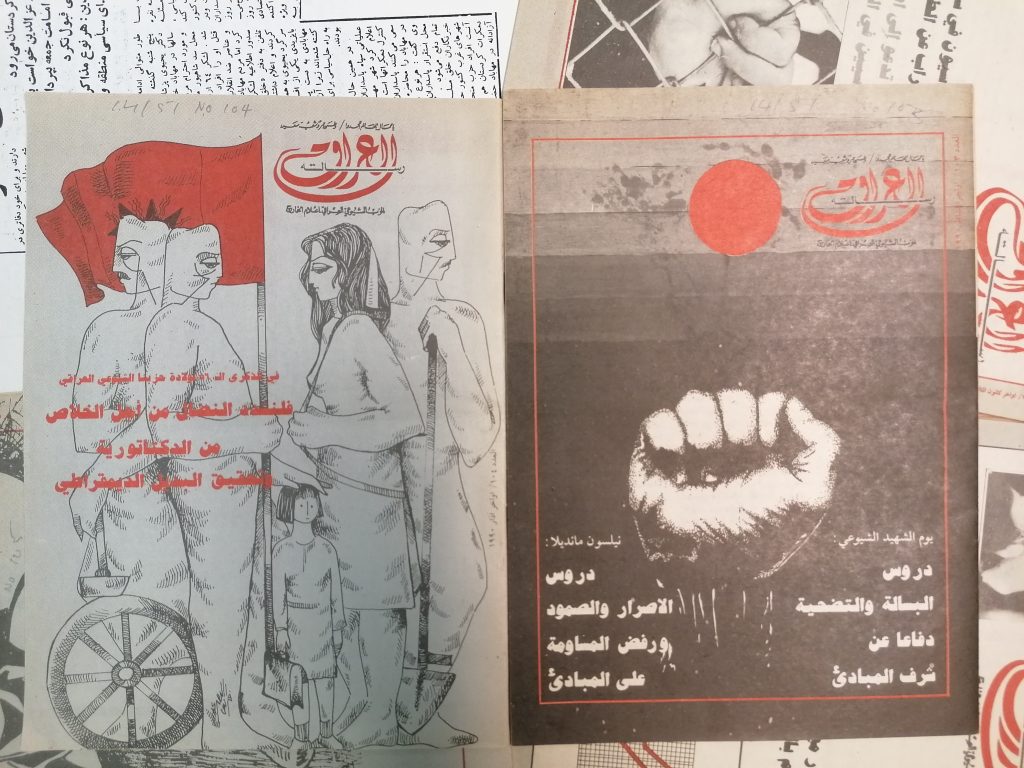

A selection of issues of رسالة اَلْعِرَاق [Risālat al-ʻIrāq] the journal of the Iraqi Communist Party, from 1979 to 1980. EUL MS 403/3/5/5

Kurdish Studies: Where Now?

‘Kurdish Studies’ is a relatively new discipline, but for much of its existence it has (understandably) been shaped by political and nationalist agendas, with the ‘Kurdish Question’ and related issues of Kurdish identity tending to dominate the field. Furthermore, it has faced the additional problem of fragmentation according to the different regions (Iran, Iraq, Turkey and Syria) in which the studies are undertaken. (Clémence Scalbert Yücel and Marie Le Ray provide an excellent explanation of these issues in their article, ‘Knowledge, ideology and power. Deconstructing Kurdish Studies’, European Journal of Turkish Studies No.5, 2006.) Matters are improving, however, with greater awareness of comparative methods and more self-reflective, critical thinking about how to address these challenges and develop a more rigorous, multi-disciplinary and transnational approach to fieldwork and other forms of research. A helpful introduction to recent developments can be found in Baser, Toivanen & Zorlu (eds.), Methodological Approaches in Kurdish Studies: Theoretical and Practical Insights from the Field (Lexington Books, 2019).

There are other challenges too: those with an interest in Kurdish studies who wish to work with original material quickly learn that some knowledge of the Kurdish language is helpful, but it may not be enough – there are significant differences between Sorani and Kurmanji Kurdish for a start, but for the wider context it may be necessary to work with documents in Arabic, Persian and Turkish (including possibly Ottoman Turkish), while the Sheikhmous archive also includes large quantities of material from the Kurdish diaspora in Europe, written in Swedish, German, Italian and French.

Examples of Italian language material in the Sheikhmous archive – an issue of Ajò, a Sardinian journal on Kurdish affairs (1982) and material published by the Italian branch of the PUK (1975). EUL MS 403/3/1/2

This does, of course, provide rich resources for those eager to purse topics across regional and national boundaries. Beyond the ‘Kurdish question’ and the traditional issues of political and diplomatic history, there are a plethora of areas of study that could be explored using the Sheikhmous archive (and some of our related collections) – the economics of the oil industry in Kurdistan for example, the role of music and culture in the Kurdish diaspora, tribalism, political parties and corruption, transnational correspondence networks, gender and feminism, women and employment, refugees and migration, comparative studies of language in print publications, graphic design in Kurdish media, folk art and political protest…. and so on.

Research has tended to focus on the Kurds of Iraq and Turkey, with the Kurdish communities in Iran and Syria receiving much less attention. The Sheikhmous archive contains a considerable amount of rare material on Iran, including copies of early publications from Mahabad, papers relating to several Iranian political parties, documentation of Iranian student movements and other papers that touch upon the political upheaval of the 1979 Islamic revolution. These are written in Kurdish, Arabic and Persian, amongst other languages, and include original documents as well as copies. Iranian Kurdish politician Abdul-Rahman Ghassemlou (1930-1989) – leader of the KDPI from 1973 until his assassination in Vienna – is represented in the archive through correspondence, presscuttings, reports written by political allies and a recorded interview. There are also papers written by and about Iranian cleric and Kurdish leader Sheikh Ezzedin Hosseini (1922-2011), as well as correspondence between Hosseini, Sheikhmous and others, and several files of papers relating to Iranian political parties such as the Democratic Party of Iranian Kurdistan (KDPI)/Ḥizb-i Dimukrāt-i Kurdistān-i Īrān, Komala/Komełey Şorişgêrî Zehmetkêşanî Kurdistan/Revolutionary Workers’ Society of Iranian Kurdistan,

The transnational political life of Omar Sheikhmous

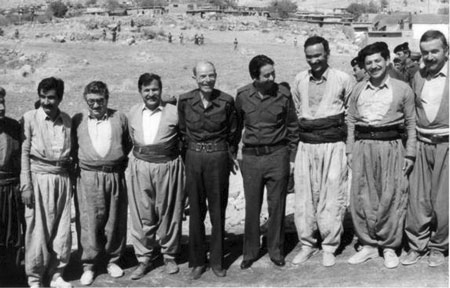

The far-ranging scope of the Sheikhmous archive does of course reflect the trajectory of his life: born in Syria, he fought with the peshmerga in Iraq, lived for a period in both the UK and the US before making his home in Sweden, all the time developing a network of contacts in both Kurdistan and across Europe. As many of the papers have been acquired during this transnational and multi-faceted career, there is the potential here for scholars of Kurdish studies to draw together documents from different countries and pursue much-needed comparative and inter-disciplinary research.

For example, there is a great deal of material (EUL MS 403/4) documenting the activities of the Kurdish community in Sweden, in which Sheikhmous was (and remains) an active member. These includes records and publicity material for cultural activities and political meetings, concerts and literary events, academic seminars and protest marches, to which can be added the files of correspondence with Swedish politicians and journalists (EUL MS 403/2/21). These could be the primary materials for a research project looking at how Kurdish national identities are created and maintained in diasporic settings. How might the experience of Kurds in Sweden compare with those elsewhere in Europe, or in Britain, Australia or the United States? We do have quite a bit of material on Kurdish exiles in Germany and Austria too, and the correspondence between these individuals and associations could provide insight into the workings of diasporic networks. What role to they play in creating and preserving Kurdish national identity?

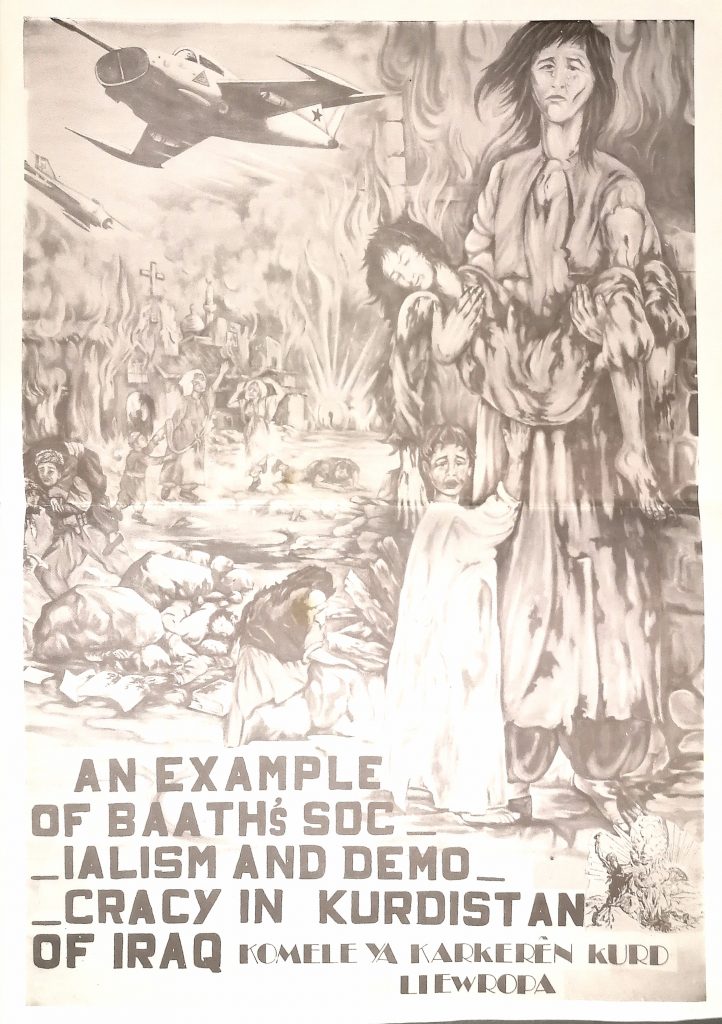

Another large section (EUL MS 403/5) documents the activities of Kurdish students across Europe from the 1960s through to the late 1980s. There are student newsletters, press releases commenting on events in Kurdistan, publications, protest posters and records of political meetings in Britain, France, Germany, America and elsewhere in Europe. It would be fascinating to look at the contrasts between Kurdish students in eastern and western Europe,or examine the relationship between events in Kurdistan and the way they were perceived by Kurdish students abroad.

Omar Sheikhmous and the Development of Kurdish Studies

Our archive also contains some of the extensive correspondence Omar Sheikhmous undertook with scholars and academics around the world, many of whom were key figures in the development of Kurdish studies as a discipline (EUL 403/3/23). These include one of the world’s leading specialists on Kurdistan, Martin van Bruinessen (born 1946), the eminent Italian scholar Professor Mirella Galletti (1949-2012), American researcher, Kurdish specialist and founder in 1988 of the Kurdish Heritage Foundation of America, Vera Marion Beaudin Saeedpour (1930-2010), Italian journalist and campaigner for the Kurds Laura Schrader (born 1938), Austrian historian of the Kurds and humanitarian worker Dr Ferdinand Hennerblicher (born 1946), Norwegian sociologist and pacifist Elise Boulding (1920-2010), Polish ethnographer Leszek Dziegel (1931-2005) and ‘Chris Kutschera’ – the pen-name used jointly by French journalist Paul Maubec (1938-2017) and his photographer wife Edith Kutschera.

Studying this correspondence might provide insights into how Kurdish studies has developed through an international network of writers and researchers, many of whom – as the selection above indicates – have worked in journalism and fields other than academia. Many of these western writers who began showing an interest in Kurdistan during the 1960s and 1970s did so as part of a wider interest in revolutionary struggles against oppression that were taking place across the world. How did their political agendas and outlooks relate to how Kurds saw themselves? Are these relationships reflected in the correspondence between the Kurdish diaspora in Europe – including the Kurdish students’ organisations – and the Kurds who remained living in Kurdistan? How have humanitarian activities and press campaigns helped to influence academic writing on the Kurds? What contribution has been made by institutions such as Vera Beaudin Saeedpour’s Kurdish LIbrary and Museum (New York), the Kurdish Library (Stockholm) and the Kurdish Academy (Ratingen)? There is a mass of original material on all these topics in the Sheikhmous archive that awaits further research.

Vol. 2, no. 3 of the periodical القافلة al-Qāfilah = Karwan, issued by the Kurdish Students’ Society in Europe,Yugoslavia Branch. EUL MS 403, Box 5. There are also press releases from the Czechoslovakian branch and hundreds of other documents produced by Kurdish students across Europe, America and the UK. Comparative studies between different student groups could be illuminating. Some more examples are shown below:

Archives and Institutions

While on the topic of Kurdish libraries and cultural centres, it would be of great value for the development of Kurdish studies if a comprehensive list of important Kurdish archival collections could be established, in order to aid research as well as to ensure the preservation of materials that might be in danger. More work needs to be done in establishing connections between these different archives, so that researchers can easily be made aware of complementary collections, and where the gaps in one archive might be filled by holdings elsewhere.

Recently we were in touch with the University of Toronto, which holds the archive of Kurdish scholar Dr Amir Hassanpour (1943-2017). The catalogue entries are available to browse here, and there is also an excellent multi-lingual finding aid if you open the PDF version). In addition to the personal papers of Dr Hassanpour, the University of Toronto was also bequested his extensive library, which includes numerous Kurdish books and periodicals. Omar Sheikhmous and Amir Hassanpour corresponded with one another, and there are files of their letters held at both Exeter (EUL MS 403/2/8) and Toronto (B2019-0004/005(32) and B2019-0004/004(04).)

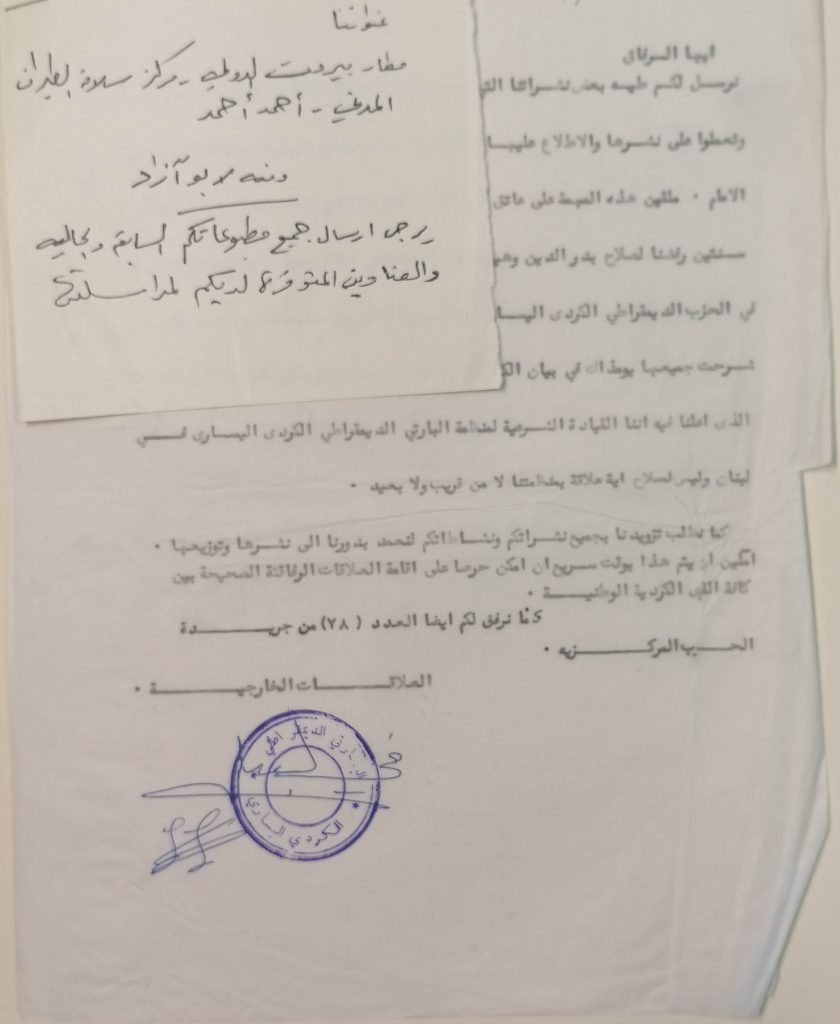

In the Sheikhmous archive at Exeter there is a large section (EUL MS 403/8) dedicated to Kurdish human rights issues, including documentation of the genocidal Anfal campaign undertaken by Saddam Hussein in 1988. Scholars working on this topic should also be aware that Sheikhmous also deposited a large collection of original documents and materials on the Anfal at the Hugo Valentine Centre in Uppsala University. A description of this archive is available here. Related material held at Exeter includes records of Kurdish appeals for humanitarian aid and for recognition of the genocidal nature of the Iraqi campaign, details of medical supplies sent to Kurdistan, documentation of human rights abuses, lists of the names of martyrs and victims of torture, publicity material protesting against the use of chemical weapons, and correspondence between Kurdish activists and western politicians, campaigners and UN officials. This material provides insights into the various strategies used to try and influence public opinion and galvanise international action, as well as the ways in which deaths and pasts sufferings have been commemorated within the Kurdish community.

Records of letters written by condemned Kurdish prisoners in Iraq (1978), EUL MS 403 Box 8.

Art, Music and Dance

While the sufferings of the Kurdish people have often been commemorated through folk songs and literature, it should be emphasised that the Sheikhmous archive also includes much wider material about the celebration and preservation of Kurdish traditions through songs, music, dance, art and literature. There are numerous cassette recordings of traditional Kurdish music, including peshmerga songs and folk music ensembles, posters for concert performances in Sweden and Britain, publicity material for poetry readings, book launches and other literary events, translations of Kurdish poetry, correspondence and other papers by Kurdish writers such as Şerko Bekas (1940-2013), Cegerxwin (1903-84) and Şahînê B. Soreklî [a.k.a. Chahin Baker, born 1946), as well as examples of artwork, advertisements for painting and photographic exhibitions relating to Kurdistan and a number of DVDs, videos and recorded interviews covering various aspects of Kurdish life, culture and political history.

This short blogpost has aimed at revealing the scope and diversity of the Sheikhmous archive, and suggesting possible ways in which its riches could be exploited for the benefit of the developing field of Kurdish studies. Anyone interested in undertaking research on these or any other topics is invited to contact Special Collections – although we are still operating a restricted service due to the current pandemic, hopefully it will not be too long before access is available. Cataloguing of the archive has been held up due to the university being under lockdown for much of the spring and summer, but this should be complete by late autumn.

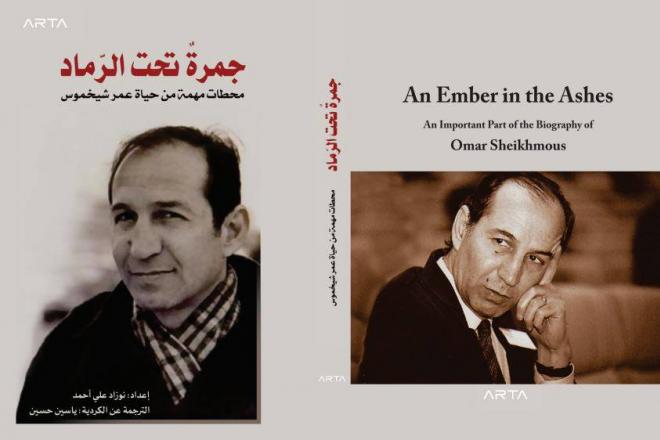

Finally, for those interested in learning more about Omar Sheikhmous, there is an Arabic biography:

جمرة تحت الرماد : محطات مهمة من حياة عمر شيخموس [Jumrah taḥta al-ramād: maḥaṭṭāt muhimmah min ḥayāt ʻUmar Shaykhimūs] is an Arabic translation by Yāsīn Ḥusayn of a text in Kurdish by Newzad ʻElî Eḧmed, based on his interviews with Sheikhmous. It was published in 2017 by the Cairo Centre for Kurdish Studies and an English translation is believed to be in preparation.

This is currently the closest thing we have to a biography of Omar Sheikhmous

In the next blogpost, we will provide a guide to the various Kurdish political parties and organisations with some examples of how each one is represented in the archive.