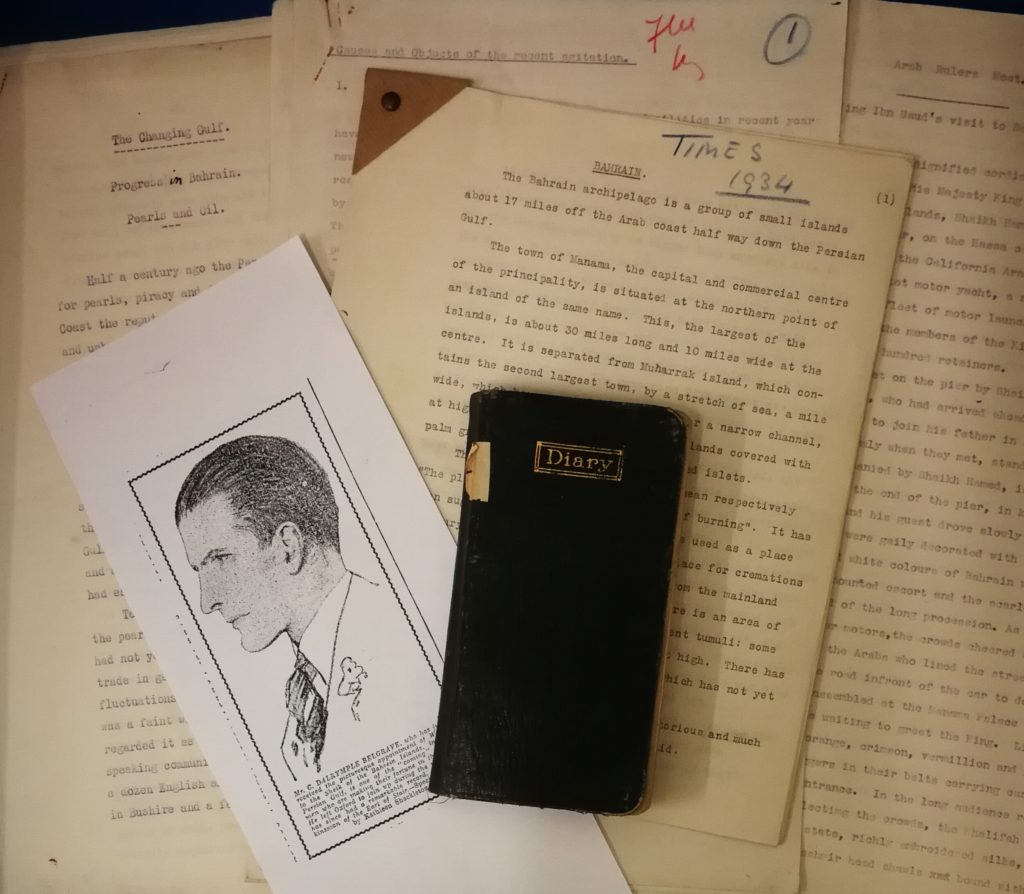

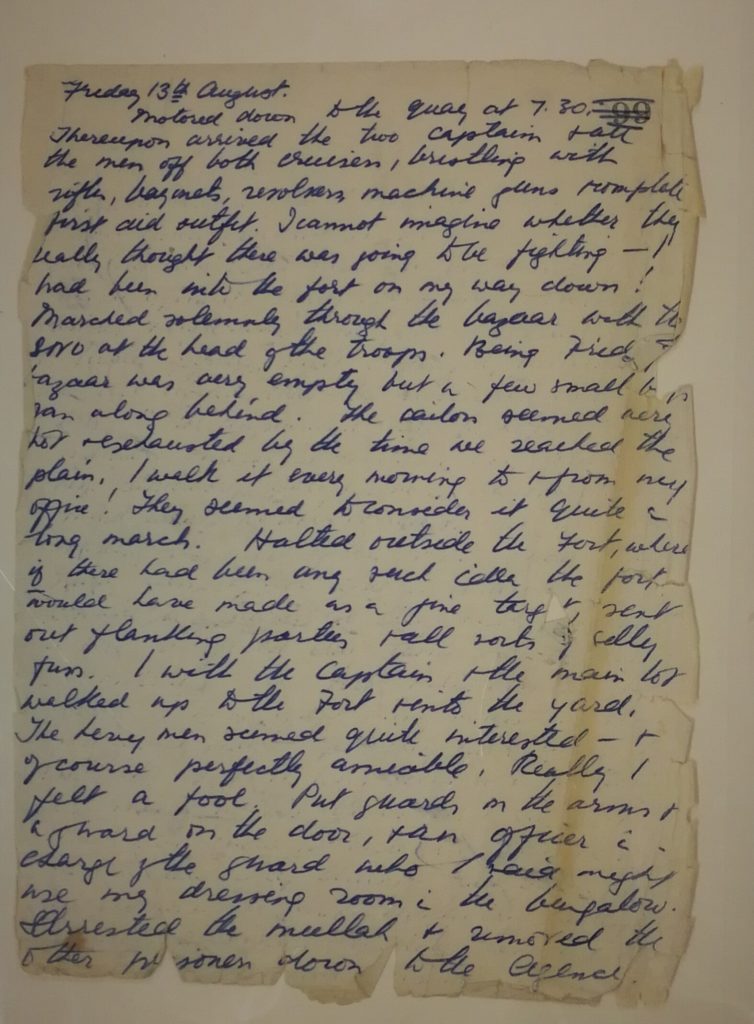

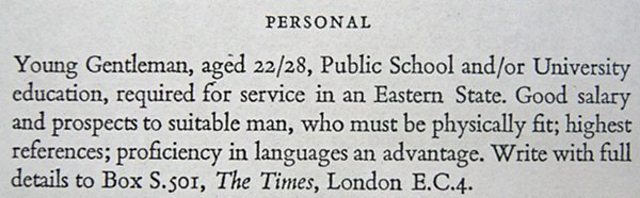

Charles Belgrave was adviser to the Sheikh of Bahrain from 1926 to 1957, and during those thirty years he was an exceptionally busy man. In addition to his duties advising the royal family and steering British policy in the region, he set up the police force, sat in judgement in the law courts, oversaw improvements in the health and education systems on the island and played a key role in supporting the establishment of the petroleum industry in Bahrain after oil was discovered in the early 1930s. He took a hands-on approach to all these activities, taking part in midnight raids on illicit arak stills, interrogating prisoners in the police cells, interviewing applicants for various posts on the island and generally involving himself in the minutiae of everyday life in Bahrain. His personal influence in the region was so extensive that he was referred to not only as المستشار (‘the Adviser’) but also as رئيس الخليج (‘Chief of the Gulf.’)

Despite this he was able to make time for leisure activities, including playing bridge, reading novels and listening to gramophone records. At times it is clear that the constant round of social engagements – integral to his job – could be intensely tedious, and there are countless references to dull dinners with ‘awful’ people and ‘sticky’ conversation. One form of entertainment that does begin to appear more and more regularly in his diary is the cinema. Although his references to picture-going are generally brief, Belgrave’s comments provide an insight not only into his taste in movies, but also into the changing nature of early cinema, different routines and patterns of cinema attendance that developed over these three decades.

The first attempt to set up a cinema in Bahrain was in 1922 when local businessman Mahmood Al Saati began running an impromptu movie house in a cottage on the north coast of Manama using a small imported projector. (Al Saati’s grandson is the filmmaker Bassam Mohammed Al-Thawadi – born 1960 – who directed Bahrain’s first feature film, The Barrier, in 1990.) However, when Belgrave arrived on the island in 1926 there is no reference in his diaries to any cinema being in operation, although he did go and see some films while in India trying to recruit policemen for Bahrain. In Karachi on 8 November 1926 he went to see Dante’s Inferno which he described as ‘rather depressing… dreary performance’. It is likely that this was not the 1911 Italian version but the more recent American adaptation directed by Henry Otto. Eight days later, still in India, he sat through ‘a very bad show called Helen of Troy – most disconnected and badly done.’ It is unclear whether Belgrave was frustrated by the film itself or the manner of its screening; problems with mutilated prints and faulty projectors would be a recurring feature of Bahrain picture-going in its early years.

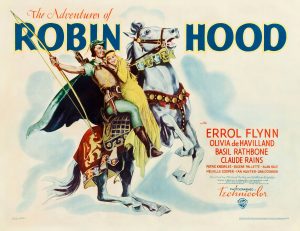

On 2 August 1939 Belgrave went to see ‘Robin Hood’ and wrote in his diary afterward: ‘coloured, rather like a pantomime, very elaborate and some beautiful scenes, but all very juvenile’.

The Yatim cinema venture

On 21 September 1927 Belgrave ‘signed the monopoly of a cinema for three years to Ali Yatim’, adding in his diary ‘Hope he will get a move on with it.’ Belgrave had encountered Ali Yatim before, describing him as a ‘one-eyed English-speaking protégé’ of the American Mission, where he had been educated. He had a brother, Mohamed Katim, who lived away but had a bad reputation for his moral behaviour and lack of adherence to Muslim laws on food and drink. Ali died before the end of the year, however, and according to local custom, Mohamed returned to Bahrain to marry his brother’s widow. Ali’s son Hussein was sent to England to be educated at a school in Brighton (Diary, 1 January 1928). Plans for the cinema continued to be discussed, with Ghaus, the Indian contractor who had accompanied Belgrave to the cinema in Karachi calling about the matter on 14 January 1928; Sheik Hamed, the ruler of Bahrain, agreed to lower the cost of the ground to be used. The following day Ghaus returned for a lengthy talk about the question of censorship, as already strong opposition was being voiced to the proposal on religious grounds: at the council meeting on 31 January there were forceful speeches against the idea of a cinema, while the local Kadis ‘sent letters of protest.’ A wealthy pearl merchant, Ali bin Seggar, came to Belgrave to express his concern that children would be tempted to go to the cinema, ‘spend money on it, and if their parent didn’t give them money, they might steal it’ (Diary, 5 February) and he returned on 11 April to make further protests about the evils of the cinema. It is clear, however, that at least some of this resistance was due to the fierce business rivalry between the Katim family and another influential merchant Yusuf Kanoo, who was leading opposition to the cinema. The dispute seems to have succeeded in stalling any progress with the Yatim cinema. Mohamed Yatim pursued other lines of business, working as an interpreter and assistant for oil contractor Major Frank Holmes, and Belgrave noted in his diary (16 May 1932) that ‘Mohamed Yatim now sells film that fits my camera.’ The following summer, young Hussein Yatim – now returned from school – ‘came to see me to ask if the Govt. would allow a cinema here.’ Belgrave discussed the matter with him but commented privately ‘it is rather a doubtful project financially.’ (Diary, 31 July 1933).

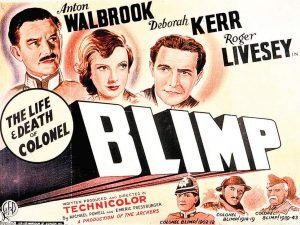

‘After quite a good dinner we went out to Awali to see a film, Col. Blimp, a very good picture, extremely English & Well acted, a long picture.’ (Diary, 17 July 1945)

Other Venues

In the meantime, the number of places where films could be screened was growing. Belgrave recorded seeing a film – ‘a talkie, which I enjoyed enormously’ – on board the naval cruiser HMS Hawkins (9 November 1933), and then another film at the Agency building (18 December 1933). The Political Agent and his staff occupied a two-storey building on the shoreline at the northern tip of Manama town, with a tennis court and pool, although it is not clear precisely when the projector was installed. Belgrave’s diary records occasions when the machine failed to work.

Oil had been discovered on Bahrain in 1932, beginning with a test well at Jebel Dukhan; a settlement of Nissan huts was built here to house the workers of BAPCO (the Bahrain Petroleum Company) which included catering and recreation facilities. Belgrave records a meeting with Percy Loch, the Political Agent, ‘to discuss a cinema at oil camp’ (Diary, 10 January 1935) and a small cinema seems to have begun operating at the Jebel camp soon after. As the oil industry developed with the construction of Sitra refinery, a new town was built on the dry plains of Awali – about twelve miles south of Manama – on a much larger scale. A cinema was also established here in 1937. Running of this cinema was taken over by a formal Club committee two years later, and Belgrave was a regular attendee of screenings here. Following the destruction of this cinema in a fire on Christmas Eve 1943, an open air screen was set up which lasted until a new auditorium was built in 1952.

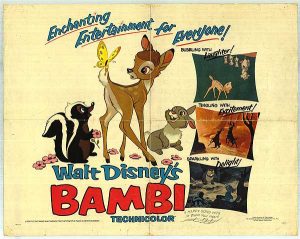

There are potential problems with having screens out in the open, and after watching Bambi here, Belgrave recorded ‘an attractive picture but the moon on the screen took much of the colour from it’ (Diary, 6 March 1944). A third cinema screen was also available at the British naval base at Juffair, on the southern edge of Manama, which was established in April 1935.

Belgrave’s diary entries during the late 1930s show that he went to watch films at Awali, Jefel and Juffair, as well as the Agency, although much of the time he just wrote ‘to cinema’ without recording the location. Many of these occasions were dictated by social engagements, with an invitation to dinner at the Agency or with oil managers followed by a film screening.

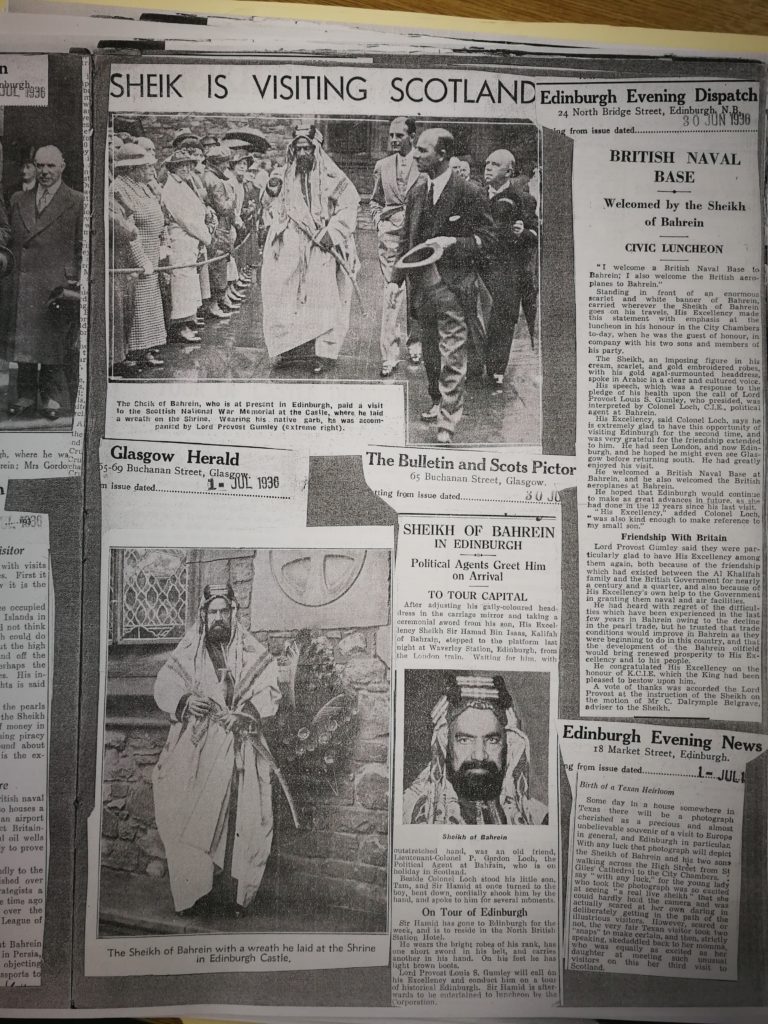

Not all these films were commercial products. The above-mentioned Percy Gordon Loch – Political Agent on Bahrain from 1932 to 1937 – was himself an amateur film-maker, as was his wife Eleanor, and screenings of their home-movies were a regular event on Bahrain’s social calendar, as is evident from Belgrave’s diary entries, for example, on 27 May, 6 November and 25 December 1933, and 8, 17 and 22 February 1934. Some three dozen of these films have been preserved in the Dalyell Collection – see here for more details.

Commercial Cinema in Bahrain

The Agency, BAPCO and naval cinemas were all of course private ventures, accessible only to employees of these particular institutions and their guests. In his Annual Report for Year 1356 (March 1937 to February 1938) Belgrave recorded that ‘Permission was granted by the Government to The Bahrain Theatre Company to open a cinema in Bahrain and a piece of ground on the south side of Manama town was leased to the company on a long lease. The company consists of several of the younger Shaikhs of the Ruling Family as well as two local Arab merchants. Building was begun during the year.’ [The Bahrain Government Annual Reports, 1924-1956. Vol.II: 1937-42. (Gerrards Cross: Archive Editions, 1986) p.24] One of these merchants was almost certainly Hussein Ali Yatim, the other being Abdulla Al Zayed (1894-1945), something of a media entrepreneur: he installed Bahrain’s first modern printing press in 1935 and four years later launched its first newspaper – Al Bahrain – which was published between 1939 and 1944.

The Manama cinema had no air-conditioning, and during the winter season screenings were held outside with the films projected onto the wall. The following year’s Annual Report noted that the cinema, which opened in the summer of 1937, showed a different picture every week, with ‘Indian, Egyptian and American films exhibited in rotation. Films are subject to Government censorship but so far only one has been prohibited as being likely to offend local taste. It is understood that the venture is proving a financial success. [The Bahrain Government Annual Reports, 1924-1956. Vol.II: 1937-42. (Gerrards Cross: Archive Editions, 1986) Year 1357, p.31] The following year saw another innovation, as the cinema began adopting the BAPCO practice of showing newsreels before the main feature, which proved so popular that many local Arabs began flocking to the cinema to see the newsreels and then leaving before the start of the movie. [The Bahrain Government Annual Reports, 1924-1956. Vol.II: 1937-42. (Gerrards Cross: Archive Editions, 1986) Year 1358, p.43]

‘James and I went to the local cinema and saw a very good film Blue Lamp about the Metropolitan police, much enjoyed it. It was quite full, a lot of 14 year old Arabs in the 3/- seats – it is amazing how they have so much money to spend. Rather hot in the cinema.’ (Diary, 18 August 1952.) James was his son, born in 1929.

Belgrave’s tastes were not widely shared among these Bahraini cinemagoers, who much preferred to go and see the latest films from Egypt. Westerners perhaps fail to appreciate that during its ‘golden age’ prior to nationalisation in the 1960s, the Egyptian film industry was the third largest in the world, with around fifty new films being produced every year – a figure that increased after the 1952 revolution led by Nasser that overthrew the monarchy. To a slightly lesser extent, Indian films were also popular, which can be linked both to the presence of a large Indian community on Bahrain and the quality of Indian film-making during the 1940s and 1950s. Egyptian films were the staple at the Pearl Cinema on Government Road, the opening of which was attended by Belgrave (Diary, 22 July 1948), and the Ahali Cinema in Manama, a commercial venture by former pearl merchant Ibrahim Muhammed Al-Zayyani that also opened in 1948. Such entrepreneurship was characteristic of the period of rapid expansion and consumerism that followed the Second World War, with the Pearl Cinema forming just part of a large business empire run by Andulaziz bin Hasan Al Gosaibi and his family, who had links to Saudi Arabia. Cinema going was now increasingly part of a new leisure culture enjoyed by a younger and more affluent Arab population, and no longer the preserve of the small Anglo-American elite as it had been in the 1930s. Belgrave’s diaries provide information not only about the growth of Bahrain’s cinema industry, but also about the cultural development of film screening practices and the changing habits of cinema-goers.

Finally, Belgrave’s diaries also reveal what he thought about dozens of well-known movie classics…

The Great Dictator (Charlie Chaplin, 1940) ‘Disappointing, some good items but it didn’t hang together – bits of slapdash comedy and rather heavy straight stuff which didn’t mix and a long dull propaganda speech to finish. A most disappointing show.’ (29 November 1941)

Jane Eyre (Stevenson, 1943) starring Joan Fontaine: ‘fairly good but too much darkness – the modern tendency in films seems to have them almost black out. I suppose it saves sets.’ (14 July 1945)

The Keys of the Kingdom (Stahl, 1944) starring Gregory Peck: ‘very well acted & close to the story but on the whole somewhat depressing, a good many people sniffed.’ (19 February 1947)

Caesar and Cleopatra (Pascal, 1945) starring Claude Rains and Vivien Leigh: ‘I was disappointed in the film, some good colour shots – but I don’t care for history brought up to date with modern slang & a very flighty Cleopatra. (23 January 1948)

Dark Mirror (Siodmak, 1946) starring Olivia de Havilland: ‘rotten, about two tiresome twins, one of whom did a murder… bored stiff’ (14 August 1948)