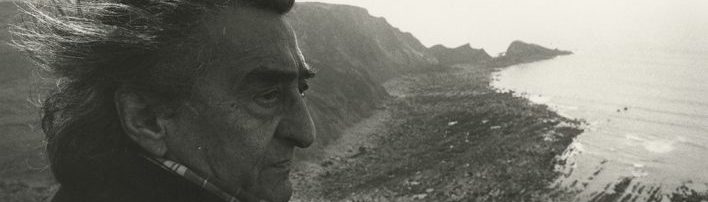

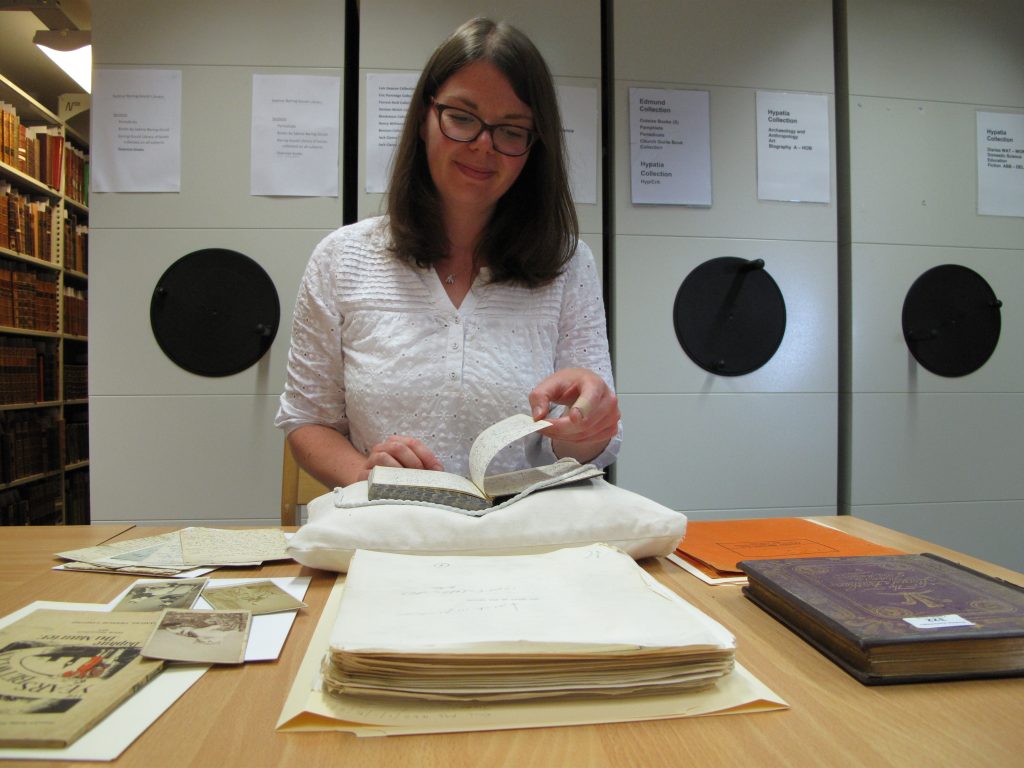

Any scholar in the UK involved in Middle East research during the second half of the 20th century would almost certainly have come across Robin Bidwell’s name. From 1968 until his retirement in 1990 he was Secretary and Librarian of the Middle East Centre at the University of Cambridge, and from 1974 he was editor of the journal Arabian Studies, which transformed into New Arabian Studies in the early 1990s. Although active as an author, researcher, correspondent, editor and PhD supervisor, he never held a formal academic post during his career and much of his work was written for a general audience rather than for specialist scholars. His papers have recently been catalogued and are now available for consultation in Special Collections, so this would be a good time to look back on Bidwell’s life and highlight areas of his work that are represented in our archives.

Robin Bidwell was born on 27 August 1927 and educated at Downside Abbey school and Pembroke College, Cambridge, where he graduated with a first in History. While a student, he took part in some elaborate pranks, such as composing ‘Letters to Anglican Divines’ that purported to be from an imaginary monk of Downside, as well as collaborating with Humphrey Berkeley in the writing of a series of fictitious letters from a headmaster named ‘H. Rochester Sneath’ that were sent out to the heads of various private schools in 1948 and – despite the absurdity of some of their contents – were taken seriously and elicited replies.

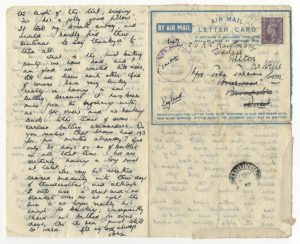

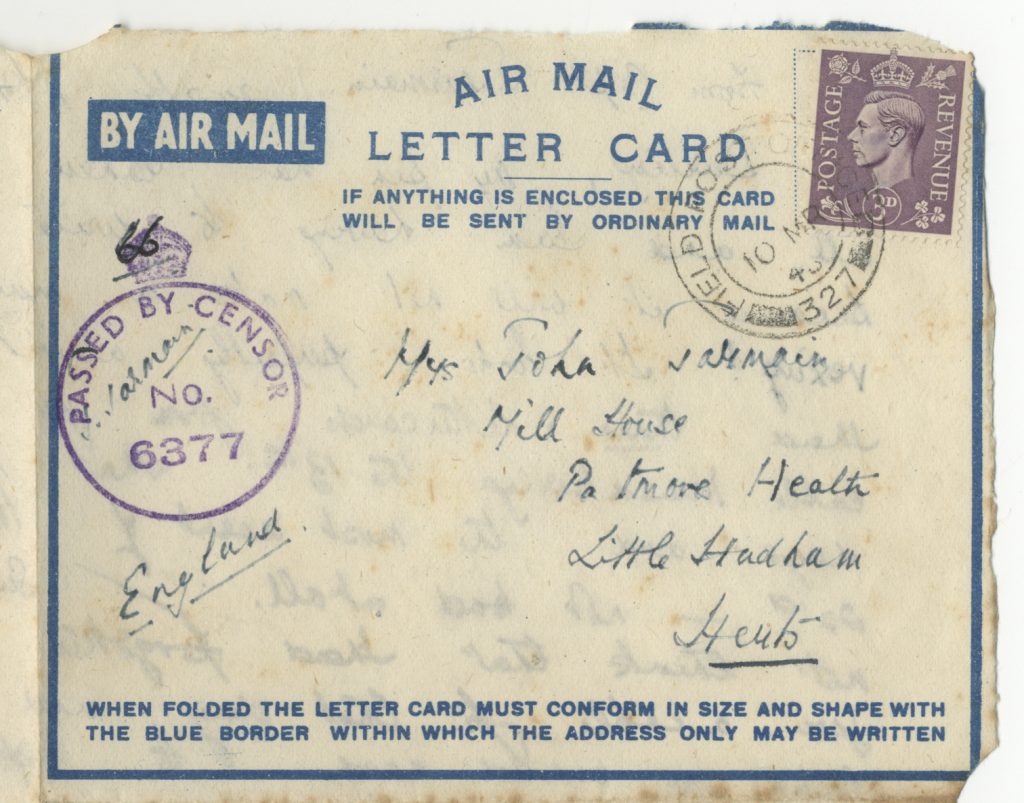

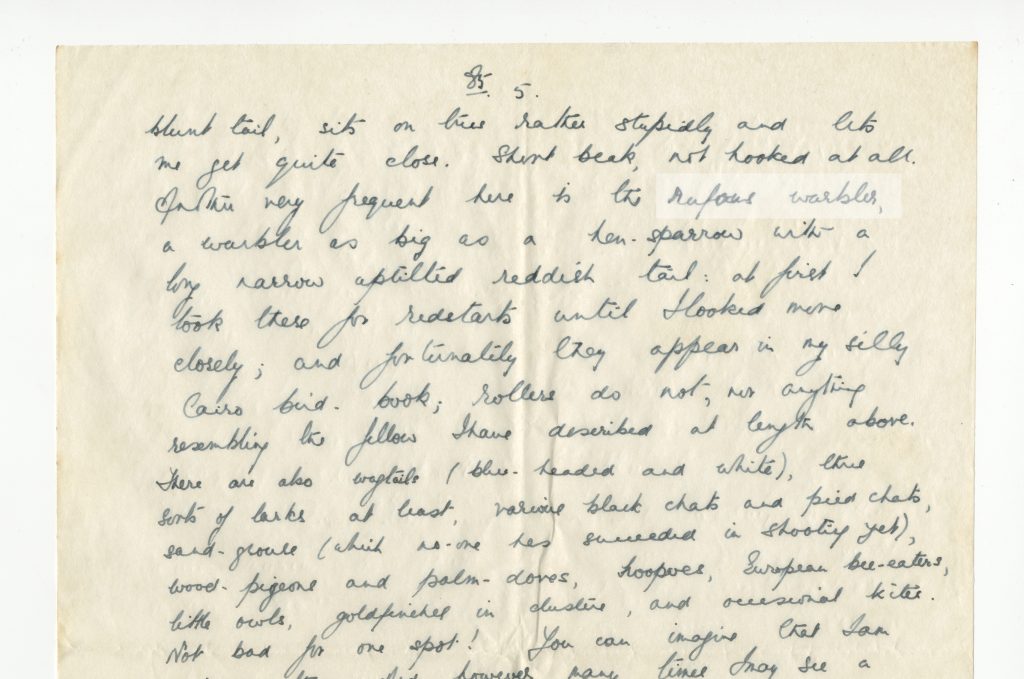

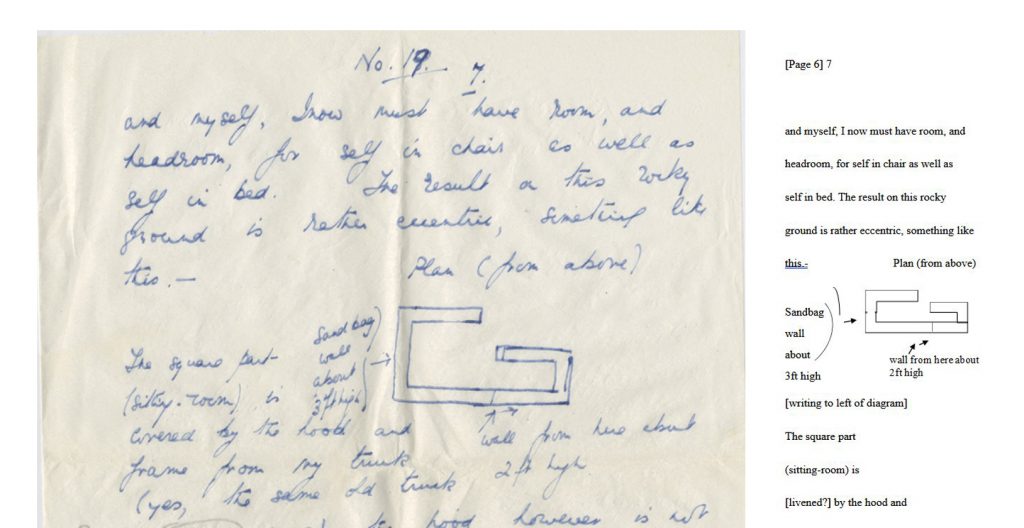

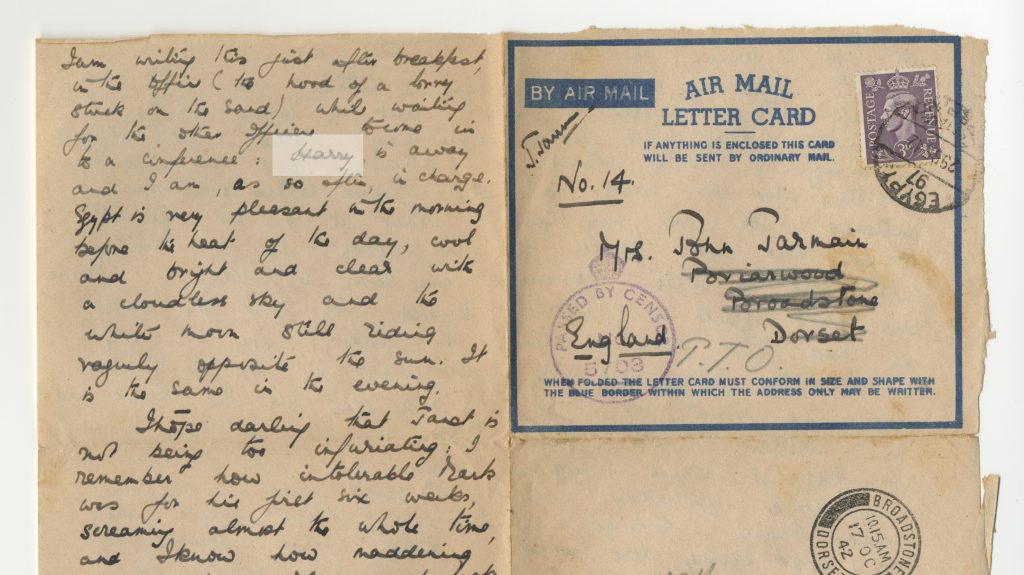

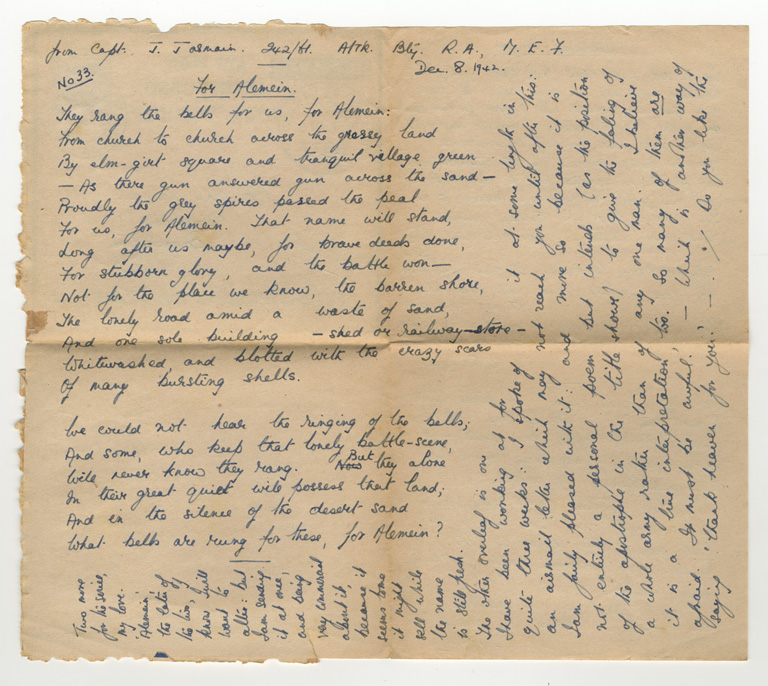

After leaving university, Bidwell was posted to Egypt as a sergeant in the Intelligence Corps serving in the Suez Canal Zone. From 1955 to 1959 he was a political officer in the Western Aden Protectorate, which began his lifelong interest in Aden, Yemen and the region of Southern Arabia. The archive contains eight letters written by Bidwell to his younger sister Dafne (who later worked for MI6) that contain some vivid descriptions of his activities in the region, including dealings with local Bedouin and tribal leaders, his appointment as adviser to the Audhali Sultan, armed skirmishes with militia, meetings with Sharif Hussein bin Ahmad Al-Habieli, the Sultan of Beihan, placements in Ahwar and Zara, visits from the Governor of Aden and from Duncan Sandys, then UK Minister for Defence, and journalist Randolph Churchill, as well as celebrations for Eid. (EUL MS 377/1/2).

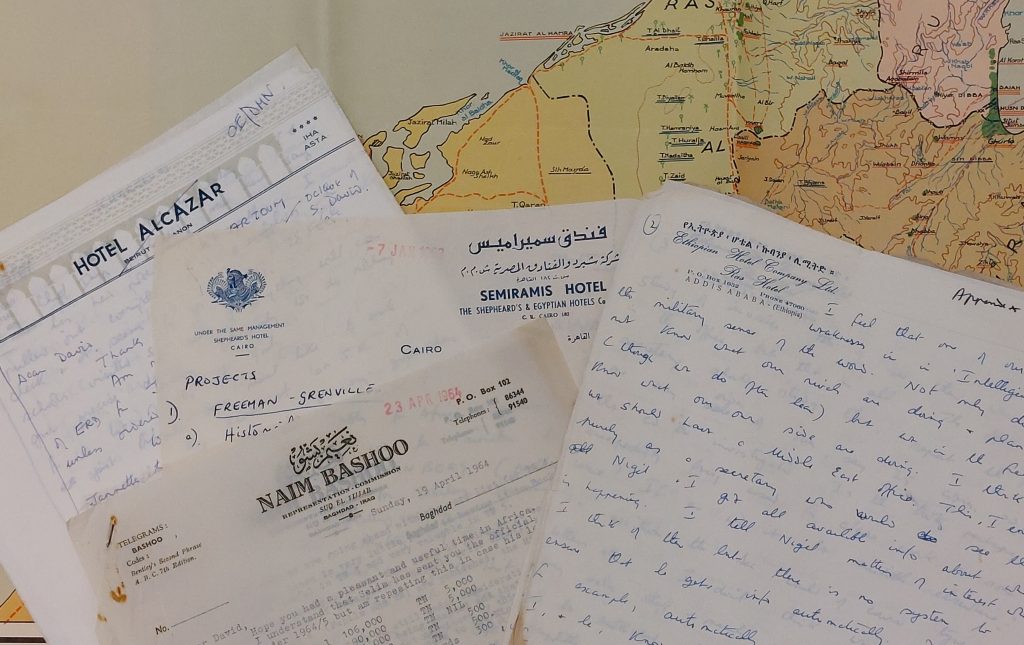

Travelling Editor for the Oxford University Press, 1962-64

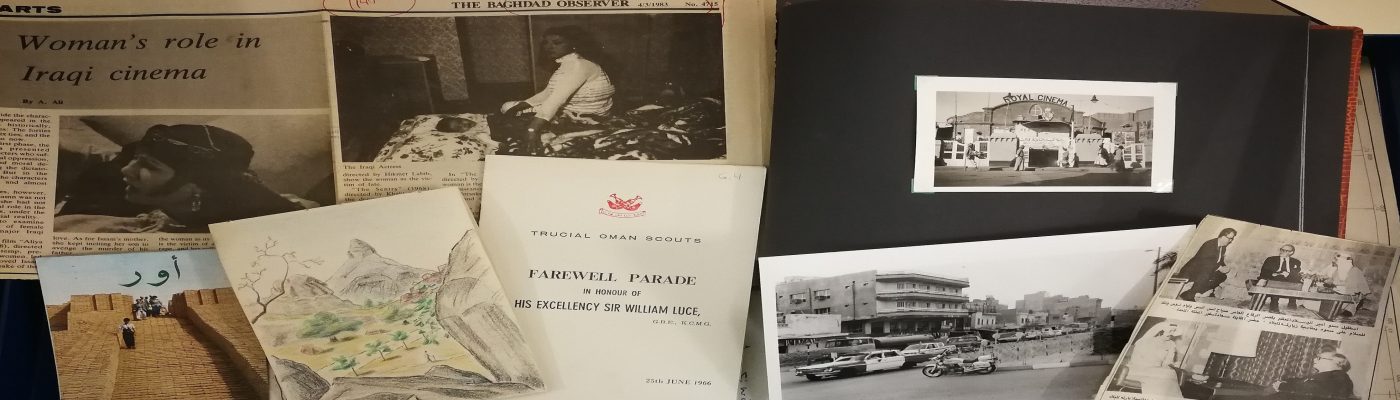

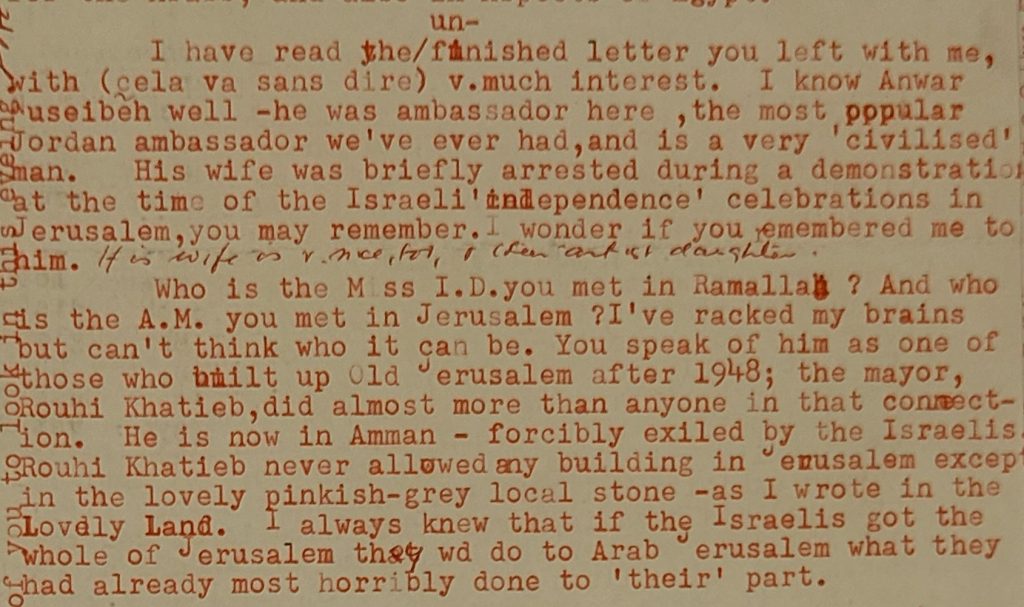

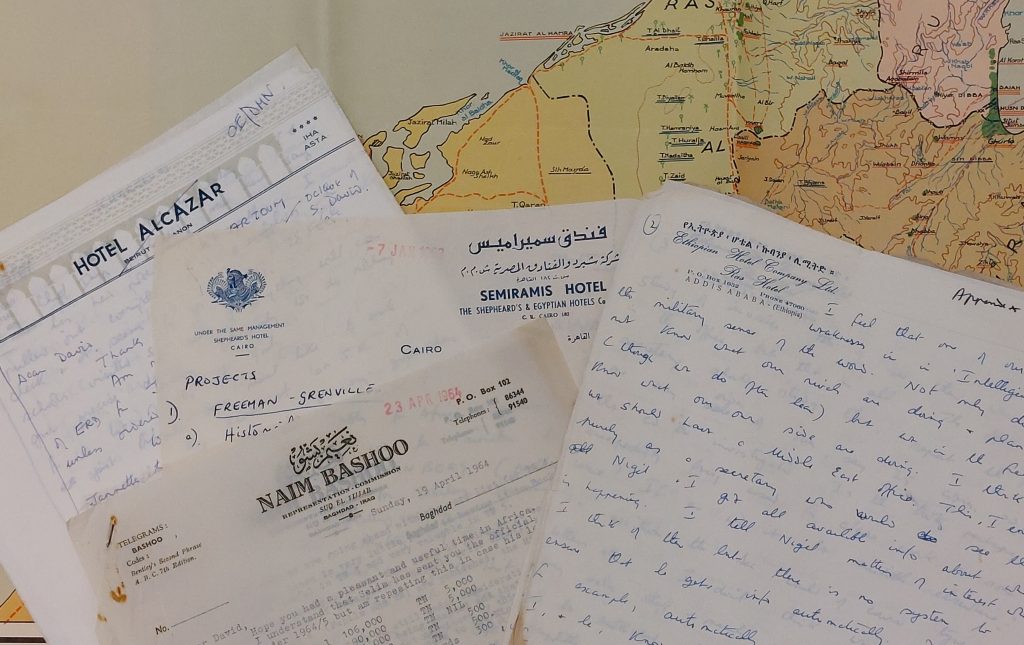

After leaving the political service, Bidwell began working for Oxford University Press and was subsequently appointed travelling editor for the Middle East market. Much of his work involved pent visiting educational institutions and reporting back on text books required for teaching, looking into issues with distribution, and exploring potential for new books and authors. During the course of his work for OUP, he travelled extensively around the Middle East and by the time he returned to the UK he claimed that he had visited every single country in the region without exception. The archive has three folders of letters – mainly to his boss, David Neale – written from hotels in places such as Accra, Aden, Amman, Baghdad, Beirut, Cairo, Damascus, Gondar, Istanbul, Jeddah, Khartoum, Rabat, Thessaloniki and Tunis, as well as a transcript of radio broadcasts in Baghdad during the coup on 18 November 1963, at which Bidwell was present, given to him by the British Embassy there (EUL MS 377/1/3). Among the many topics discussed is a possible blackmail attempt against lexicographer A.S. Hornby, whose Advanced Learner’s Dictionary of Current English (ALDCE) was one of the books Bidwell was distributing widely in the Middle East.

Cambridge University

Bidwell returned to Cambridge in 1965, where he began studying for a PhD on the French administration in Morocco under Professor Bob Serjeant, who became a mentor, lifelong friend and collaborator. He completed his PhD in 1968, and that same year was appointed Secretary and Librarian of the Middle East Centre, which had been established in 1960 by the famous orientalist Professor Arthur John Arberry. He was a key player in the development of Middle Eastern studies at Cambridge, building up the Centre’s library collections, teaching a popular undergraduate course on modern Arab history and organising a successful programme of seminars.

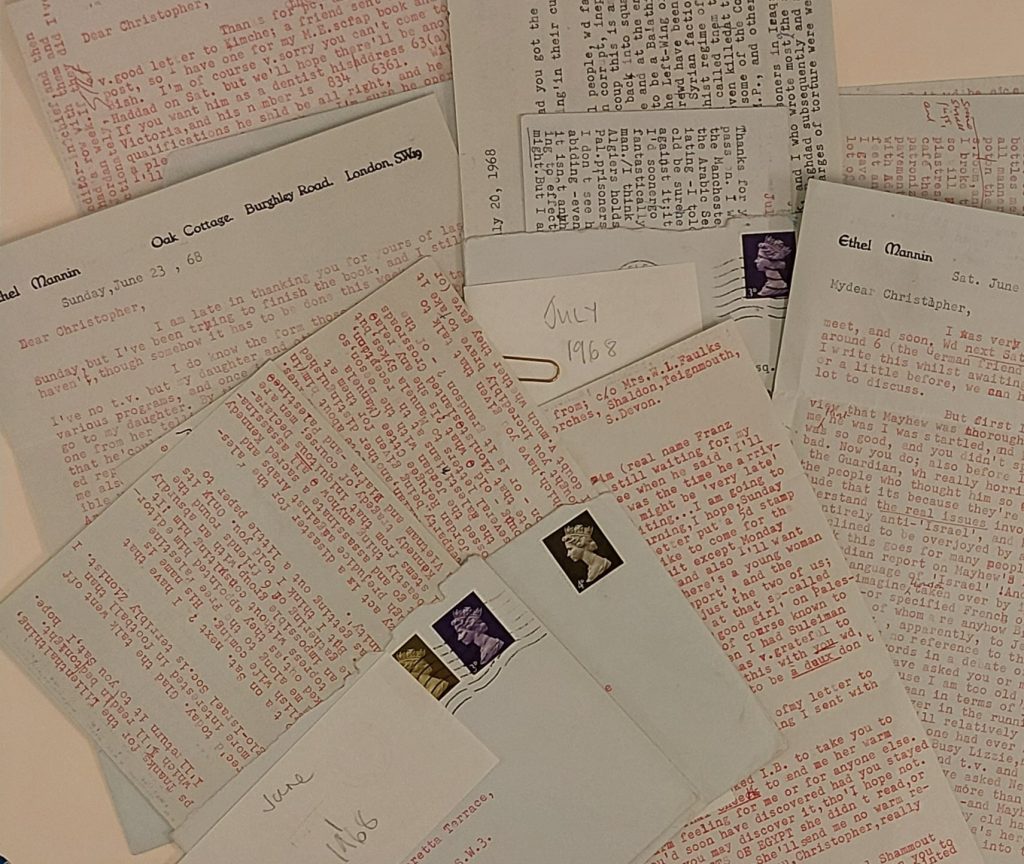

There are many letters and documents relating to his work at Cambridge, including correspondence with a wide range of scholars and researchers such as Albert Hourani, Henry St John Basil Armitage (1924-2004), Lebanese scholar on Persia and Islam, Victor El-Kik (1936-2017), Gerald de Gaury (1897-1984), Tim Mackintosh-Smith and Professor G. Rex Smith, Jordanian historian Suleiman Mousa (1919-2008), Sir Ronald Wingate (1889-1978), as well as diplomats and political officials including the British ambassadors to North and South Yemen, the Kuwaiti Ambassador to the UK, Salem al-Sabah, and Qatari minister Ali Al-Ansari. There are also administrative documents, letters and reports on PhD matters, folders of teaching and lecture notes, as well as an amusing compilation of jokes, comic verse, newspaper misprints and other examples of ‘college humour’.

In the early part of his research career Bidwell became frustrated at the amount of work needed to calculate the past values of currencies, and decided to draw up his own conversion tables and publish them for the benefit of other scholars. His first published book was therefore, unusually for a Middle East scholar, Currency conversion tables: a hundred years of change (London: Rex Collings, 1970). In a similar way, his recognition of the difficulties faced in obtaining information about minor government officials resulted in the publication of his four-volume work, A Guide to Government Ministers, published in four volumes between 1973 and 1978, and covering the UK, western governments, the Arab World and Africa. If you needed to know who the Minister for the Interior in Egypt was in 1920, or the succession of Defence Ministers in Burma in the 1950s, Bidwell’s Guide probably had the answer. The internet may now provide some of this information, but Bidwell’s labours remain a valuable resource.

Although Bidwell learned some Arabic while working in the Western Aden Protectorate, he never progressed beyond a fairly basic knowledge of the language, which meant that most of his research focussed upon either English language or translated sources.

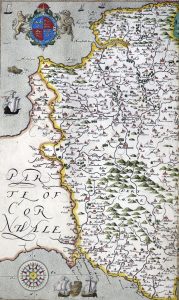

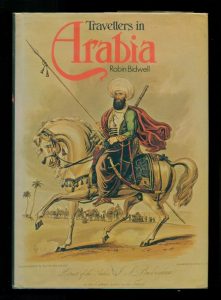

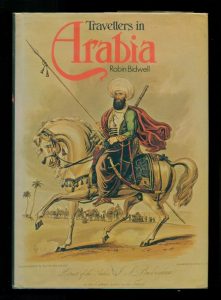

For this reason, he was particularly interested in the history of European engagement with the Middle East, which was the subject of his book Travellers in Arabia (1976). Covering the period from the 16th to the mid-20th centuries, Bidwell provided portraits of the explorers, soldiers, archaeologists and writers who had travelled around the Arabian peninsula, such as Carsten Niebuhr, Richard Burton, Charles Montagu Doughty, Wilfred Thesiger and Freya Stark. Written with a light, irreverent touch, Travellers in Arabia was nonetheless underpinned by Bidwell’s solid knowledge of the region’s history and topography. During the course of his career, Bidwell read widely and prolifically on the Middle East, recording each book with a sheet or two of typed notes on which he picked out the salient points or summarised arguments with a short quote or two. We have hundreds of these sheets of typed notes, which include 19th century biographies in English and French, academic studies and meticulously annotated archival sources from the Public Record Office and other archival institutions in the UK and France. A large proportion of the books relate to the subject of European travel and were clearly the raw research for Travellers in Arabia. Although the organisation of these typed notes is not very user-friendly, they could be useful for students or researchers seeking an introduction to the historical literature on some of these topics.

Morocco and North Africa

Bidwell had not forgotten about Morocco, the subject of his Ph.D, which was published by Cass as a monograph as Morocco under colonial rule: French administration of tribal areas 1912-1956 (London: Cass, 1973) and began working on a history of Morocco that drew extensively upon the accounts of European travellers, rather like his book on Arabia. Its working title was Morocco through Western Eyes, but during the 1980s – partly in response to correspondence with publishers and editors (which is also preserved in the archive) – he reshaped the material into a more thematic structure, and the book was eventually published in 1992 as Morocco: The Traveller’s Companion. There are two boxes of notes, drafts, research material and other papers relating to this project, including typed summaries of travel accounts and extensive notes from Foreign Office records.

Other material on Morocco and the neighbouring countries in North Africa include documentation relating to the 1970 Constitutional Referendum, five folders of press-cuttings (1988-92) that cover events such as the Polisario Front conflict with Morocco, the violent protests in Algeria’s ‘Black October’, reforms and protests in Tunisia, and Libya’s international relations. These are interleaved with Bidwell’s typed notes, summarising and commenting on political events, and there are also a series of typescripts by Bidwell that provide a chronological account of events in Algeria between 1989 and 1992, covering such topics as the impact of the Gulf War, the resignation of President Chadli and the assassination of Mohammed Boudiaf. There is also an envelope containing 69 commercial postcards of Algeria and Morocco, dating from the 1920s through to the 1990s and showing street scenes and views of Algiers and Fez, Meknes, Moulay-Idriss and Tetuan, Marrakesh and Casablanca, the Botanical Gardens in Algiers, traditional costumes and crafts such as basket-making, musicians, markets, festivities and rituals.

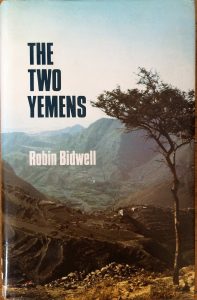

Yemen and Aden

There is even more material on the history of Yemen and Aden, much of it relating to Bidwell’s research for his book The Two Yemens (1981), which was a detailed history of both North and South Yemen from the 19th century down to the present.

Like many of Bidwell’s books it was written for a general reader, for which reason he deliberately omitted source references and kept the bibliography to a minimum. At times the book perhaps veers into an overly romanticised and orientalist depiction of the region, and it is at its strongest in its analysis of postwar political developments, and the complex relations between the various factions in North and South Yemen during this period. This was of course something of which he had direct experience, as the area of the Aden Protectorate had largely fallen under the auspices of The Federation of South Arabia, which merged with the Protectorate of South Arabia to form the People’s Republic of Southern Yemen in 1967, despite tensions and rivalry between the National Liberation Front (NLF) and FLOSY (Front for the Liberation of Occupied South Yemen). In the North, the old Kingdom of Yemen became the Yemen Arab Republic in 1962, and the ‘two Yemens’ retained an occasionally troubled relationship until their unification in 1990. Bidwell’s account of their history is enlivened by his views on British diplomatic, political and military personalities, many of whom he knew.

In addition to numerous folder of notes and typescripts, there are annorated presscuttings documenting events in the two Yemens throughout the 1980s, a folder of PDRY publications, annotated copies of the Western Aden Protectorate Handbook from the 1950s, as well as a mass of secondary material, articles, essays, offprints, official records and reports. There is also a set of three large black bound folders containing photocopies articles and documents on the Hadhramaut region of South Arabia (now in eastern Yemen) with some other travel narratives concerning Aden and Yemen, including writings by J.T. Bent, Majid Khadduri, St John Philby, W.H. Ingrams (six articles, comprising the whole of Folder 2), Freya Stark, Elizabeth Monroe and D. van der Meulen.

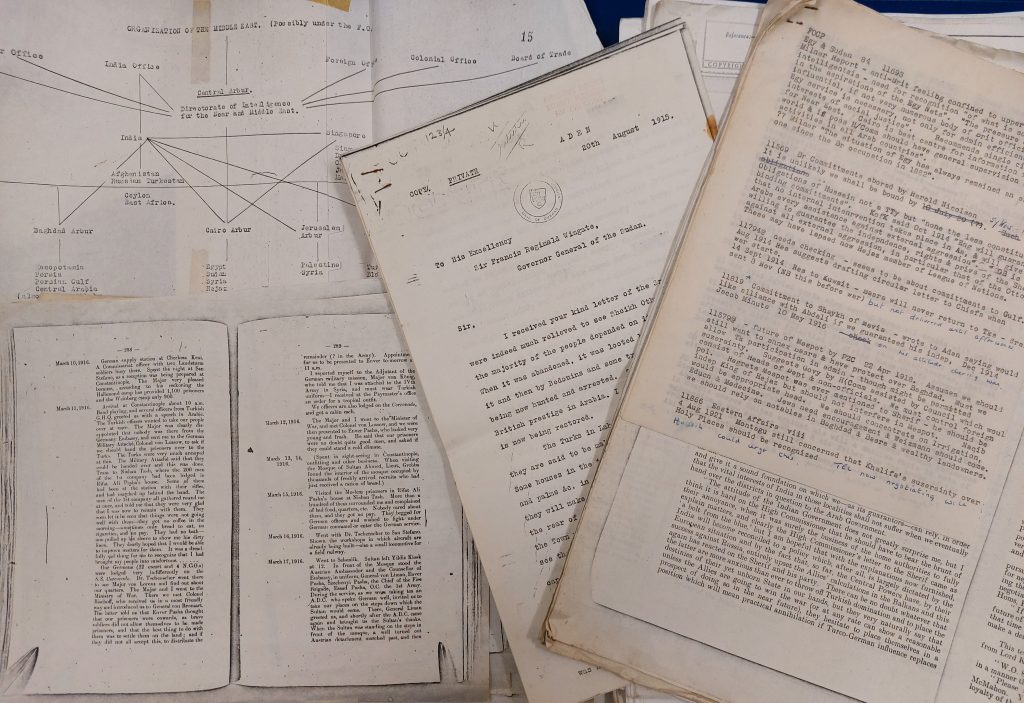

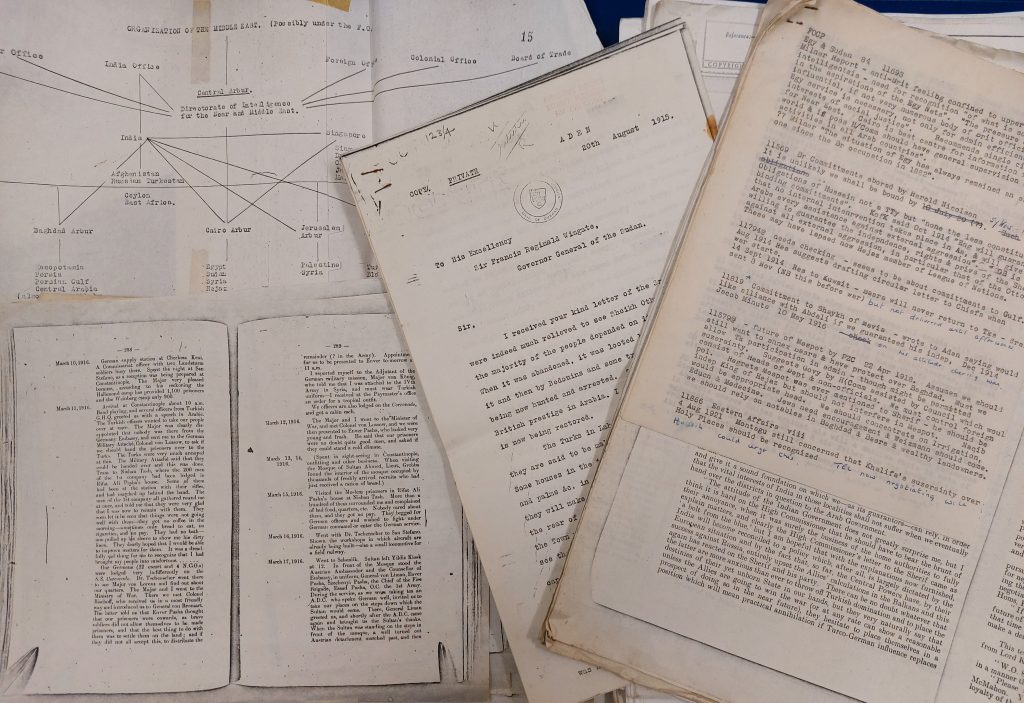

Archival and Editing Work: the Arab Bureau and the Ottoman Empire

Much of Bidwell’s research was carried out in archives in the UK, France and further afield, and he made particularly extensive use of Foreign Office Confidential Print (FOCP) sources. These were printed copies of telegrams, despatches and other documents that were reproduced and circulated to officials in the Foreign Office from the 1820s through to 1914. He carried out important work editing publications for the Foreign Office, such as the The affairs of Arabia, 1905-1906 (2 vols, 1971) and The affairs of Kuwait, 1896-1905 (1971), and he also edited 28 volumes of British documents on foreign affairs: reports and papers from the Foreign Office confidential print. Part 2, From the First to the Second World War. Series B, Turkey, Iran, and the Middle East, 1918-1939 (Frederick, Md.: University Publications of America, 1985-97.)

He amassed a large collection of documents for this work, many of which were not selected for inclusion in the published volumes, and which now offer researchers a wealth of information on British foreign policy during the closing years of the Ottoman Empire.

For many years Bidwell was particularly interested in the Arab Bureau, which was founded in 1916 on the initiative of Mark Sykes with the aim of collecting intelligence information and disseminating propaganda. Headed by Brigadier-General Gilbert Clayton, David Hogarth, and Kinahan Cornwallis, staff of the Bureau included Gertrude Bell, T.E. Lawrence, Aubrey Herbert, George Ambrose Lloyd and William Ormsby-Gore. Moving away from the traditionally harmonious relations between Britain and Turkey (as exemplified by papers in the Whittall archive, EUL MS 259), the Bureau began demonising the Ottoman Turks and pushing a narrative of an Arab nationalist revival that would supporting the Arab Revolt against their Ottoman rulers. As subsequent events would show, however, British assurances to the Arab leaders turned out to be worthless, and the post-war era would see much of the former Ottoman Empire come under the control of the British Empire.

Bidwell acquired a large collection of documents relating to the history of the Bureau and also corresponded with surviving members or their descendants – these letters are among the large box of research papers on the topic (EUL MS 377/2/1/.) Although he went on to edit The Arab bulletin: bulletin of the Arab Bureau in Cairo, 1916-1919 (4 vols, 1986), for which he provided an introduction and notes, it appears that he intended to write a larger monograph on the Arab Bureau – something that has since been done by Bruce Westrate, author of The Arab Bureau: British Policy in the Middle East, 1916-1920 (2010). There is still a great deal of intriguing and unused material in Bidwell’s papers however.

Later career, marriage and the Dictionary of the Modern Arab World

Robin Bidwell was over fifty when he married educational psychologist Margaret Luft. They lived in the Suffolk village of Coney Weston where they were soon joined by a daughter, Leila. He retired from his role as Secretary of the Middle East Centre in 1990 and was therefore able to devote more time to the project that had been his main focus attention for several years, the creation of a Dictionary of the Modern Arab World. He was seated at his desk at home working on this when he died of a heart attack on 10 June 1994.

The Dictionary is a monumental achievement that contains over 2000 entries, selected and written in Bidwell’s own idiosyncratic style, with pithy statements and lively opinions on personalities (many of whom were still alive) as well as lengthier, perceptive essays on a range of topics and historical events, informed by Bidwell’s firsthand knowledge. It is not a conventional encyclopedia by any means, and in its unfinished state created some challenges for the publishers, who finally got it into print in 1998. We have fifteen boxes containing Bidwell’s typed entries for the Dictionary, many of which were not used in the published version.

His other great work was the journal Arabian Studies, eight volumes of which he co-edited with Bob Serjeant: Vol. I (1974), Vol. II (1975), Vol. III (1976), Vol. IV (1978), Vol. V (1979), Vol. VI (1982), Vol. VII (1985) and Vol. VIII (1990.) Problems arose regarding funding for the publication, which led to the editors deciding to break away from its association with the Middle East Centre at Cambridge and start a new journal, New Arabian Studies, the first volume of which was published by Exeter University Press in February 1994, shortly before his death. Sadly, Bob Serjeant never lived to see this, having died in 1993. The dispute over control of the journal is recorded in detail in the correspondence files, as is Bidwell’s editorial work and communications with authors.

Catalogue entries for the Bidwell papers can be found here.

Publications by Robin Bidwell

Currency conversion tables: a hundred years of change.

London : Rex Collings, 1970

The affairs of Arabia, 1905-1906 / edited with extensive new material and a new introduction by Robin Bidwell.

London: Frank Cass, 1971

The affairs of Kuwait, 1896-1905 / edited with extensive new material and a new introduction by Robin Bidwell.

London: Frank Cass, 1971

Morocco under colonial rule: French administration of tribal areas 1912-1956

London: Frank Cass, 1973.

Bidwell’s Guide to Government Ministers (London: Frank Cass, 1973-74. 3 vols.)

Volume 1: The major Powers and Western Europe 1900-1971 (1973)

Volume 2: The Arab world 1900-1972 (1973)

Volume 3: The British Empire and Successor States, 1900-1972 (1974)

Volume 4: Guide to African ministers

London: Rex Collings, 1978.

Travellers in Arabia

London: Hamlyn, 1976

The two Yemens

Harlow: Longman, 1983

Arabian and Islamic studies: articles presented to R.B. Serjeant on the occasion of his retirement from the Sir Thomas Adams’s Chair of Arabic at the University of Cambridge. Edited by R.L. Bidwell and G. Rex Smith.

London: Longman, 1983

British documents on foreign affairs: reports and papers from the Foreign Office confidential print. Part 2, From the First to the Second World War. Series B, Turkey, Iran, and the Middle East, 1918-1939 / editor: Robin Bidwell [and Bülent Gökay]. (Bidwell edited Part II, Series B, Vols.1-28)

Frederick, Md.: University Publications of America, 1985-97.

The Arab bulletin: bulletin of the Arab Bureau in Cairo, 1916-1919 / with a new introduction and explanatory notes by Dr.Robin Bidwell.

Gerrards Cross: Archive Editions, 1986 [4 v.]

Arabian personalities of the early twentieth century

Cambridge: Oleander, 1986.

Morocco: the traveller’s companion. (Co-written with Margaret Bidwell).

London: I.B. Tauris, 1992

The diary kept by T. E. Lawrence while travelling in Arabia during 1911 / [introduction by Robin Bidwell].

Reading: Garnet, 1993

Dictionary of modern Arab history: an A to Z of over 2000 entries from 1798 to the present day / London: Kegan Paul, 1998

Articles

‘Middle Eastern Studies in British Universities’

Bulletin (British Society for Middle Eastern Studies)

Vol. 1, No. 2 (1975), pp. 84-93

‘A French Family in the Yemen, by Louise Fevrier’ ‘Queries for Biographers of T.E. Lawrence’ Arabian Studies Vol.III (1976)

‘Bibliographical Notes on European Accounts of Muscat 1500-1900’

Arabian Studies Vol.IV (1978)

‘The Political Residents of Aden: Biographical Notes’ Arabian Studies Vol.V (1979)

‘T.E. Lawrence in French Military Archives ‘ and ‘The Turkish Attack on Aden 1915-1918’ Arabian Studies Vol.VI (1983)

Robin Bidwell, “The Brémond Mission to the Hijaz, 1916–17: A Study in Inter-Allied Co-operation,” in Arabian and Islamic Studies: Articles Presented to R. B. Serjeant on the Occasion of His Retirement from the Sir Thomas Adam’s Chair of Arabic at the University of Cambridge,

(London: Longman, 1983)

‘A Collection of Texts dealing with the Sultanate of Muscat and Oman and its International Relations, 1790-1970’ Journal of Oman Studies, Vol.6:1 (1983)

‘The Old Moroccan Army’, Mars and Minerva (SAS Regiment Journal) Vol.6:1 (Summer 1983) pp.26-8

‘The Reformed Moroccan Army 1860-1912’, Mars and Minerva (SAS Regiment Journal) Vol.7:1 (Autumn 1985) pp.28-30

‘Visitors to San’a’ Arabian Studies Vol.VIII (1990)

Book reviews

Brian Doe, Socrata (in British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies Vol.19:2, 1992) p.219-220

James Simmons, Passionate Pilgrims (in the Middle East Journal, Vol.42:2, Spring 1988) p.332-333 J.G. Lorimer, Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf, (Geographical Journal, Vol. 138:2, June 1972) pp.233-5

Michael Meeker, Literature and Violence in Northern Arabia (Journal of Arabic Literature, XII, 1981) pp.160-161