The 22nd of November 1963 was the day of John F. Kennedy’s assassination. The first broadcast assassination of a world leader, the murder of the President of the USA at the height of the Cold War, this was the epicentre of a political and media cataclysm the resultant ripples of which are still present in our thinking.

The 22nd of November 1963 was also Benjamin Britten’s 50th birthday – occurring on the feast day of St Cecilia, patron saint of music. Despite some public fanfare, Britten’s birthday must have been all but forgotten in the furore emerging from the USA.

In her diary entry for the day, Rose Marie Duncan, Ronald Duncan’s wife, noted both events:

‘Bunny rang up in evening to say Kennedy had been shot. State of shock and amazement and real sorrow – watched T.V – news etc – and also tribute for B[enjamin] B[ritten]’s 50th birthday – rather boring and sententious – shot of R[onald] in very long floppy shorts, going off to play tennis, flanked by Ben and Peter like warders.’

The next entry continues the connection in the most unexpected of ways:

‘Still upset about Kennedy’s death. Watched 1-0 news on TV – pictures of Mrs K and general mix up – also the assassin – looking like a young Benjamin B[ritten]!’ (Rose Marie Duncan, 1963 Diary, EUL MS 397/18/1/9)

At 50, and a year on from his completion of his seminal War Requiem, Britten was no longer the ‘promising young composer’ to whom Ronald Duncan had been introduced, probably in 1936, by his college friend Nigel Spottiswoode. (Ronald Duncan, All Men Are Islands, Rupert Hart-Davis 1964, p. 130) Facilitated by the interest of all three men in the Peace Pledge Union and by Spottiswoode’s involvement in the production of the GPO Film Unit’s enduringly popular Night Mail (for which Britten wrote the score), the introduction led to a fast friendship between the two writers and instigated a creative exchange that would interest them for the remainder of their careers.

The first buds of this exchange appeared in the form of the Pacifist’s March, a ‘youthful’ work which Britten apparently showed little interest in revisiting later in life; (Duncan, 1964, p. 131) their creative engagement blossomed more fully in the late forties, following Duncan’s intervention in the libretto for Peter Grimes. This period saw the creation of The Rape of Lucretia, which was swiftly followed by works including a wedding anthem (Amo ergo sum) for their mutual friends George Lascelles (Lord Harewood) and Marion Stein, and music for the plays This way to the tomb, Stratton, and The eagle has two heads. Not all of their ideas were to come to fruition, and it is tantalising to know of works that were never realised, including at least one opera (based on Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park), a large work referred to in correspondence as St Peter, and a response to the bombing of Hiroshima (referred to as Mea Culpa), which Duncan lamented as the potential War Requiem that never was. (Humphrey Carpenter, Benjamin Britten: A Biography, Faber and Faber, 1992, pp. 242, 405; correspondence, Benjamin Britten to Ronald Duncan, EUL MS 397/644)

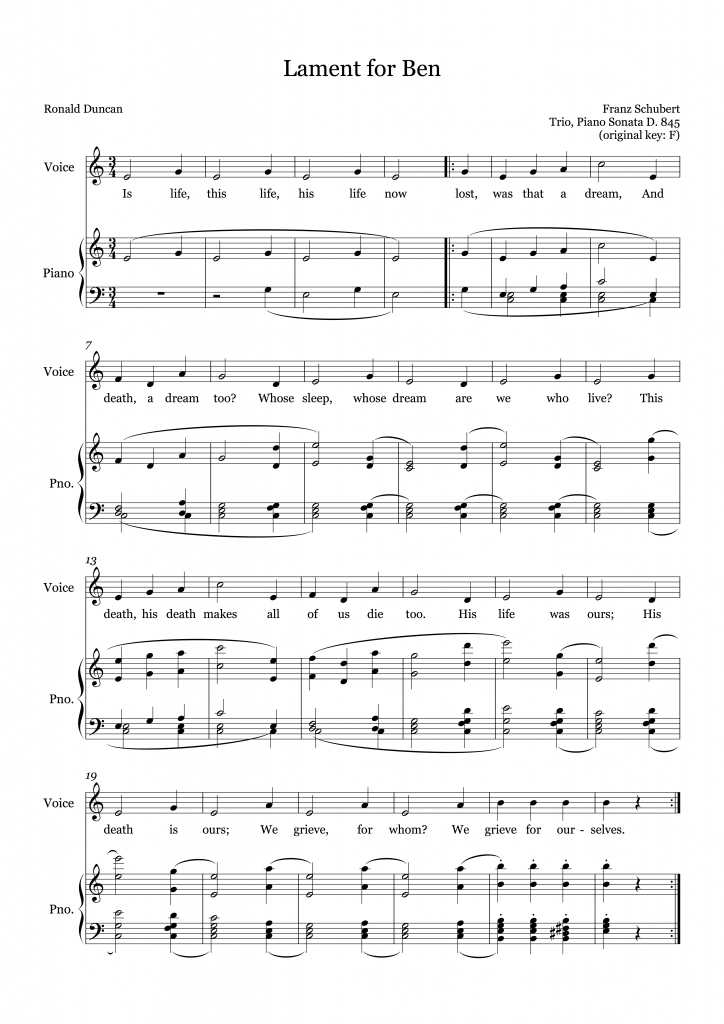

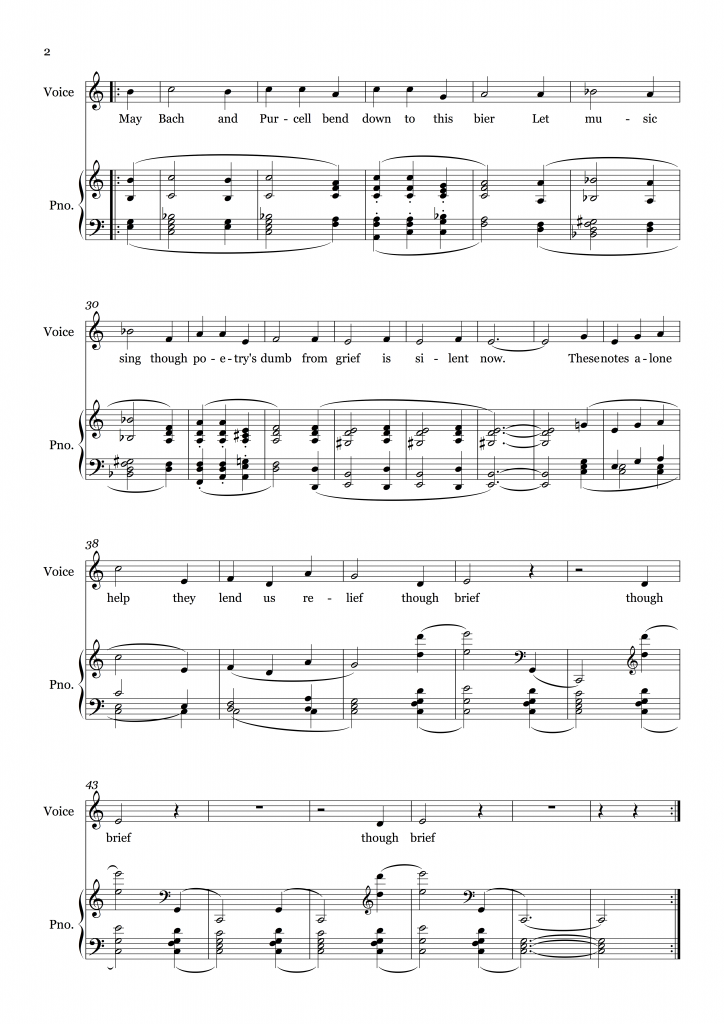

The traces of their friendship and collaboration kept in the Ronald Duncan Collection include photographs, libretti, news-cuttings, programmes, letters, copies of musical scores, and audio recordings including elements of the rehearsals for This way to the tomb. Amongst the more touching items is Lament for Ben (EUL MS 397/1046), a song contrafacted by Duncan from the trio of Schubert’s Piano Sonata in A minor (No. 16, D. 845). Duncan underlaid the score in minute and heavily revised scrawl with a new poem lamenting the passing of his great friend, and signed it at the foot of the page ‘RD. 4.XI.76’ (Britten died on the 4th of December 1976, rather than the indicated November). The choice of Schubert is a poignant one: not only was Schubert Ronald Duncan’s favourite composer, but Britten himself performed and recorded a not inconsiderable number of Schubert’s works, and would play some of them for Duncan in the early days of their friendship. In his autobiography, All men are islands, Duncan wrote: ‘Britten and I were now constant companions. He used to play Schubert to me. I had been looking for Britten for ten years. Sometimes he would play Chopin, but it was Schubert that I would make him play over and over again.’ (Duncan, 1964, p. 132) And so, almost exactly forty years later, Duncan memorialised Britten through a piece that Britten may well have played for him in their youth.

The text of this appropriated song is barely legible in situ, but the poem Lament for Ben appears in the collected poems – albeit in a form that does not quite match the lyric so tortuously worked out under the musical score. Working from both the manuscript and the published poem, I have attempted to reconstruct this very personal tribute. In order to do so, I have blended the printed poem with that of the manuscript, adjusted one or two rhythms and word placements, and transposed the piece into a key more amenable to the average voice. Finally, I have made a recording of myself singing and accompanying the song to give a sense of what Ronald Duncan may have had in mind – possibly its first singing in any public sense.

And so, with apologies for the recording quality and my mid-November cold-filled voice, a musical offering from the Ronald Duncan collection in time for Britten’s birthday on the feast of St Cecilia: a song which, by coincidence, is not wholly inappropriate to the more lamentable events for which the date is sometimes remembered.

This post was written by our Digital Support Officer Andrew Cusworth.

Recorded in the Mary Harries Memorial Chapel, University of Exeter, with thanks to the chaplaincy and director of chapel music for permission for the use of the piano and chapel.

Lament for Ben

(to Schubert’s Trio Opus 42)

Is life, this life, his life

now lost, was that a dream,

And death, a dream too?

Whose sleep, whose dream

Are we who live?

This death, his death

makes all of us die too.

His life was ours;

His death is ours;

We grieve, for whom?

We grieve for ourselves.

May Bach and Purcell

Bend down to this bier

But let music sing

to sing their song

Their song, their song

Though poetry’s dumb.

In this waste, this grief

these notes alone lend us

yields us

give us

some relief

though brief

though brief

(Ronald Duncan, ed. Miranda Weston-Smith, Collected poems, Ronald Duncan Literary Foundation, 2003, pp. 226-7)

An adapted score for Ronald Duncan’s ‘Lament for Benjamin Britten’ set to the Trio from Schubert’s Piano Sonata D845

Why not try playing it for yourself?