You may have seen that the Syon Abbey archive was in the news recently! On Tuesday 12 March 2019, an article was published in The Times concerning a letter written by Sister Catherine ‘Kitty’ Witham to her mother in 1756. The letter, which is part of the Syon Abbey archive, vividly describes the Great Lisbon Earthquake of 1755 and its consequences for the nuns of Syon Abbey. The University of Exeter’s press release about the letter can be read here.

There were several reasons why we wanted to raise awareness of Sister Kitty’s letter in the archive. Extracts from the letter have been published before, so it is not a new discovery as such, but until now it appears to have only been examined as an account of the earthquake. What we thought made this letter doubly interesting is the vivid description of the earthquake and the information we can glean from it about the lives of Sister Kitty and the Syon nuns.

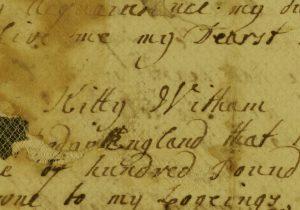

Signature of Sister Kitty Witham from a letter (EUL MS 389/PERS/WITHAM)

Sister Kitty seemed a particularly interesting nun to focus on. In 1749, at the age of about 32, Sister Catherine Witham made her vow of profession as a choir nun at Syon Abbey in Lisbon, where she died 44 years later in 1793. Apart from these bare facts, we would know very little of Sister Kitty, had she not written the letter about the earthquake, inscribed six manuscripts, and added her notes in several of the printed books in the library. Not only do we learn details of her religious and personal life from these records, but also an indication that she enjoyed (and I would argue, had a talent for) writing. As Sister Kitty’s presence can be found across the three main parts of the Syon Abbey Collection – the archive, the library, and the medieval and modern manuscript collection – she seemed the ideal person through which to highlight and raise awareness of the wider collection.

This blog post will explore some of the items in the Syon Abbey Collection that relate to Sister Kitty, allowing us to discover more about this remarkable woman and her life at Syon Abbey. It also includes details about a second letter from Sister Kitty, a copy of which surprisingly found its way to us following the publication of the article in The Times – so do keep reading for more information!

Sister Kitty in the Archive

The first item to explore is, of course, the letter of Sister Kitty Witham regarding the Great Lisbon Earthquake. Dated 27 January 1756 – almost two months after the initial earthquake on 1 November 1755 – Sister Kitty writes to her ‘dear[e]st Mama’ from ‘Poor Sion Houes‘, with a paragraph at the end of the letter addressed to her ‘Dear[e]st Aunt Ashmall’. In the letter, Sister Kitty describes the earthquake which ‘began like the rattleing of Coaches‘ and resulted in the walls ‘A Shakeing, & a falling down‘. She also gives an account of the destruction of the city of Lisbon – ‘them that has seen Lisbon befor this dreadfull Calammety & to see itt Now would be greatly Shockt the Citty is Nothing but a heep of Stones‘ – and the fates of various of its inhabitants, including the President of the English College.

But what do we learn about the nuns of Syon Abbey? Firstly, we gain insight into their morning routine. Sister Kitty sets the scene: ‘that Morning we had all been att Communion, I had done the quire & then went to gett Our Breakfasts, which is tea & bread & butter when tis not fasting time, we was all in diferent places in the Convent, some in the Refectory, some in there Cells, Others hear & there; my Lady Abbyss her two Nices Sis[te]r Clark & my Self was att Breakfast in a little Rome by the Common which when they had done they went to prepair for Hye Mass, which was to be gin att ten a Clock. I was washing up the tea things, when the Dreadfull Afaire hapend‘. We also learn that all the nuns of Syon Abbey survived the earthquake, which killed thousands of others in Lisbon, as Sister Kitty writes, ‘so Blessed be his holy Name we all mett together, & run no further neither had we Any thoughts of runing Aney futher, we was all as glad to See One another Alive & well as Can be Expresst‘. Describing the aftermath of the earthquake and the many aftershocks, Sister Kitty explains that the community first slept under a pear tree (‘for Eeight days, I & some Others being so vere frighted Every time the wind blode the tree, I thought we was A going‘), then later a ‘little place with Sticks & Coverd with Matts‘, before moving into a ‘Woden houes Made in the garden‘.

And what do we find out about Sister Kitty? One of the most powerful features of the letter is Sister Kitty’s honesty about her feelings of anxiety following the earthquake. Aftershocks from the earthquake appear to have continued for several months, leaving the nuns ‘with agreat deell of fear, & Aprehension‘, and uncertain of their fates. Sister Kitty is clearly aware of her own mortality (‘if the Earthquake had hapend in the Night as itt did not thank God, we should all or Most of us been Killd in Our Beds‘) and seems convinced the end of the world is nigh, writing ‘Only God knows how long we have [to?] live for I belive this World will not last long‘. We also discover that Sister Kitty had a very close relationship with her family and friends in England, and that she appears to have remained in regular contact with them. Throughout the letter she frequently refers to and enquires after friends and family, and towards the end of the letter she sends her regards to her father, promising ‘not to be so troublesom as I have been‘.

The letter from Sister Kitty is very fragile, with some damage and evidence of historic conservation efforts. It is also slightly mysterious, as it remains unclear how this letter addressed to her mother found its way to the community and into the Syon Abbey archive. However, there are a number of early to mid-twentieth-century transcripts of the letter in the archive, suggesting the letter was in possession of the community for at least 50 years before Syon Abbey closed in 2011. What we do know is that the letter was kept in the safe at Syon Abbey, indicating how special it was to the community.

[slideshow_deploy id=’1256’]

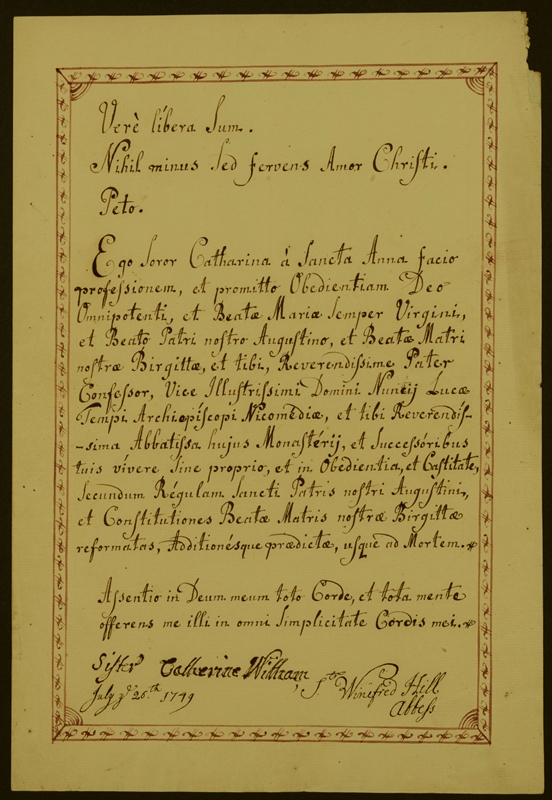

Another trace of Sister Kitty in the archive is her vow of profession. One of the great highlights of the Syon Abbey archive are the 296 vows of sisters recorded between 1607 and 2010 – and Sister Kitty is amongst them. Her vow is recorded in Latin in a document dated 26 July 1749, signed by ‘Sister Catherine Witham‘ and the abbess ‘S[is]ter Winifred Hill’, and decorated with a red border.

EUL MS 389/COM/2/1/4/23 – Vow of Sister Catherine Witham, dated 26 July 1749. Provided for research and reference only. Permission to publish, copy, or otherwise use this work must be obtained from University of Exeter Special Collections (http://as.exeter.ac.uk/heritage-collections/) and all copyright holders.

More than 150 years after the Great Lisbon Earthquake, Sister Kitty’s name reappears in the archive. Correspondence dated 1911 from a relation of Sister Kitty mentions a painting of the nun in their possession [ref: EUL MS 389/COR/1/1/19]. However, there is no other trace of this painting in the archive, and its whereabouts remain unknown.

Sister Kitty in the Manuscript Collection

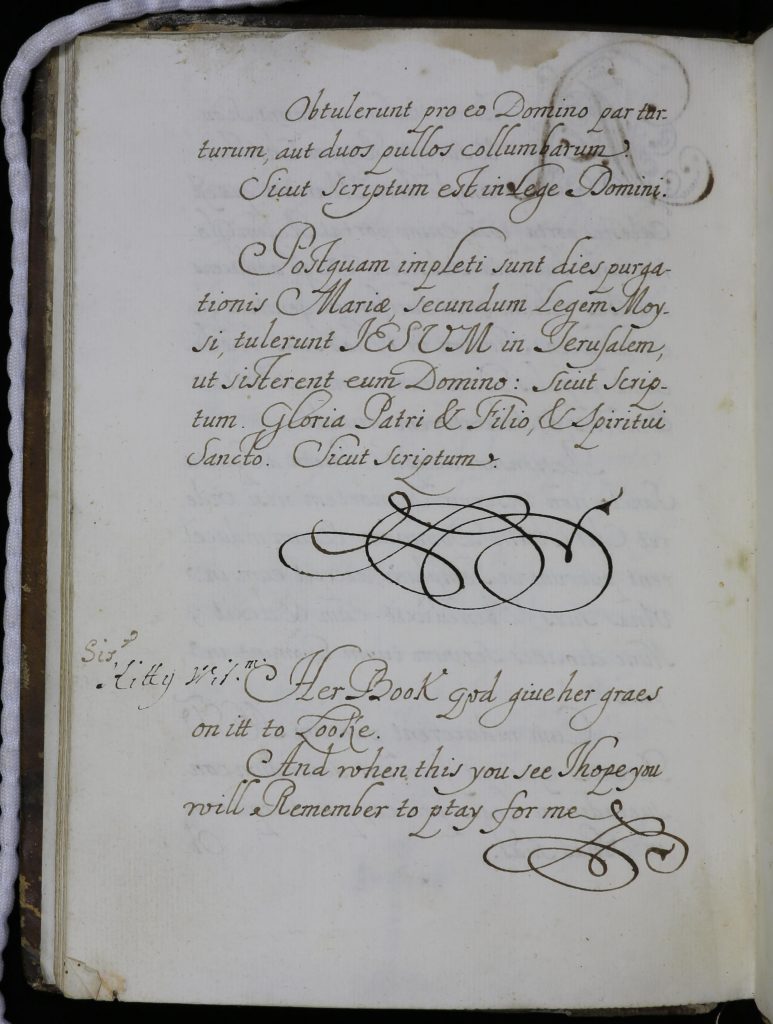

Sister Kitty’s name appears in several of the modern manuscripts in the collection. The collection includes six manuscripts either completely transcribed by Sister Kitty, or containing inscriptions by her. Some examples of inscriptions by her include: ‘ ‘Sis[te]r Catherine de S[an]ta. Anna Witham her Book with leave‘ [EUL MS 262/add2/14] and ‘Sister Catherine Witham de S[an]ta. Anna her Book of Delight, given her by the good Sister Monica Hodgson in 1753‘ [EUL MS 262/add1/31]. The image below is from a manuscript containing a transcript of the Stations of the Cross by Sister Kitty, entitled ‘Estacao’ [EUL MS 262/add2/25]. It includes the note:

‘Sis[te]r Kitty Wit[ha]m

Her Book god giue her graes

on itt to Looke.

And when this you see I hope you

will Remember to pray for me’

EUL MS 262/add2/25 – Manuscript volume entitled ‘Estacao’. Provided for research and reference only. Permission to publish, copy, or otherwise use this work must be obtained from University of Exeter Special Collections (http://as.exeter.ac.uk/heritage-collections/) and all copyright holders.

Sister Kitty in the Library Collection

Not only has Sister Kitty inscribed six manuscripts, but her notes can also be found in several printed books in the Syon Abbey Library Collection. However, there has not yet been a survey undertaken to identify all the volumes containing inscriptions by Sister Kitty. A recently-catalogued book in the library was found to have some particularly interesting notes by Sister Kitty in its flyleaves [Syon Abbey 17–/CAT]. Entitled ‘Officium B. Mariae‘, it includes several pages of Sister Kitty’s notes, as well inscriptions of names of other nuns. Sister Kitty signs the first flyleaf ‘Sis[te]r Catherine de Santa Anna Witham her Book of Consolation‘, and the following pages contain prayers and notes. In light of the letter concerning the Lisbon Earthquake, the second flyleaf is particularly interesting: a transcript of a prayer entitled ‘in time of Earthquakes‘. The same page includes a note of the marriage of her ‘Nephew & Nece Frankell‘, again indicating a close relationship with her family in England. Images of the flyleaves of this book can be viewed in the slideshow below.

[slideshow_deploy id=’1266’]

A surprise letter from Sister Kitty!

We received a wonderful surprise in the week following the publication of the article in The Times! A copy of a second letter by Sister Kitty was kindly donated to our collections by her five-times-great-nephew. Dated 1763, eight years after the Great Lisbon Earthquake, it is once again addressed to ‘My Dear Mama‘. The contrast between the two letters is striking; the second letter finds Sister Kitty noticeably happier, without the uncertainty and fear that had gripped her while she was writing the first letter. Two passages in the letter particularly stood out to me. In the first, she reflects upon her decision to become a nun, and writes: ‘tis Certainly a most happy Life & for my part I like itt every Day better & better & rejoice for haveing made such a happy happy Choice’. In the second, she reports on her role that week as hebdomadary (person appointed for the week to sing the chapter mass and lead the recitation of the canonical hours) in the abbey. She writes: ‘my Duty this week is hebdommadarium which in there weeks Officiates the Devine Office in the quire[.] they rise the first & rings the Bells & give the Nuns Lights[.] this we have in Our turns from the Oldest to the youngest in the convent[.] I darsay was D[ea]r Mama to hear me Sing in the quire she would be much Delighted for they tell me I have a very sweet voice which I thank God for itt as its a good talent for a Nun’. Despite knowing that the convent in Lisbon was rebuilt soon after its destruction and community life continued at Syon Abbey, it is comforting to have this written confirmation that Sister Kitty found happiness and hope in life again after surviving a terrible natural disaster.

Conclusion

I hope you have enjoyed discovering more about Sister Kitty Witham with me! This blog post has focused only one sister in Syon Abbey’s 596-year history; however, the Syon Abbey Collection contains many more stories of the remarkable women who joined this community. The archive, manuscripts and books are now all catalogued and available to access at the University of Exeter. For more information about the wider Syon Abbey Collection, please do take a look at our guide, which you can find here.

I would like to extend my most sincere thanks to Emma Sherriff and Connor Spence in the Digital Humanities Lab at the University of Exeter for creating high-resolution images of the letter, vow, and book of Sister Kitty Witham.

By Annie, Project Archivist

A summary of material relating to Sister Catherine ‘Kitty’ Witham in the Syon Abbey Collection:

EUL MS 389/COM/2/1/4/23 – Vow of Sister Catherine Witham (1749)

EUL MS 389/PERS/WITHAM – Manuscript letter from Sister Kitty Witham to her mother (1756)

EUL MS 389/COR/1/1/19 – Bundle of correspondence, W-Z

EUL MS 459 – Photocopy of a letter from Sister Catherine Witham of Syon Abbey to her mother in 1763

EUL MS 262/add1/29 – Small manuscript volume entitled ‘The Testament of the Sovle Made By S. Charles Borromeus, Card[inal] & Arch Bishop of Milan’ (1749)

EUL MS 262/add1/30 – Manuscript volume of prayers for the use of Sister Catherine [Kitty] Witham (c 1749-1793)

EUL MS 262/add1/31- Manuscript volume entitled ‘The Practice of the Spirituall Exercises of Saint Ignatius. The inscription on the flyleaf reads: ‘Sister Catherine Witham de S[an]ta. Anna her Book of Delight, given her by the good Sister Monica Hodgson in 1753’ (1753)

EUL MS 262/add2/14 – Manuscript volume marked ‘M.S. 14’ and entitled ‘Howe and why our office is to be sayd every day In the Hours’ (c 1749-1793)

EUL MS 262/add2/24 – Manuscript volume marked ‘MS 24’ and entitled ‘A Collection of Small Prayers either Daily Or Frequently said in Community. For the use of Sister Kitty Witham’ (c 1761)

EUL MS 262/add2/25 – Manuscript volume entitled ‘Estacao’ (c 1749-1793)

Please note: the Syon Abbey Library Collection includes a number of books containing inscriptions by Sister Kitty, but a comprehensive survey has not been undertaken.