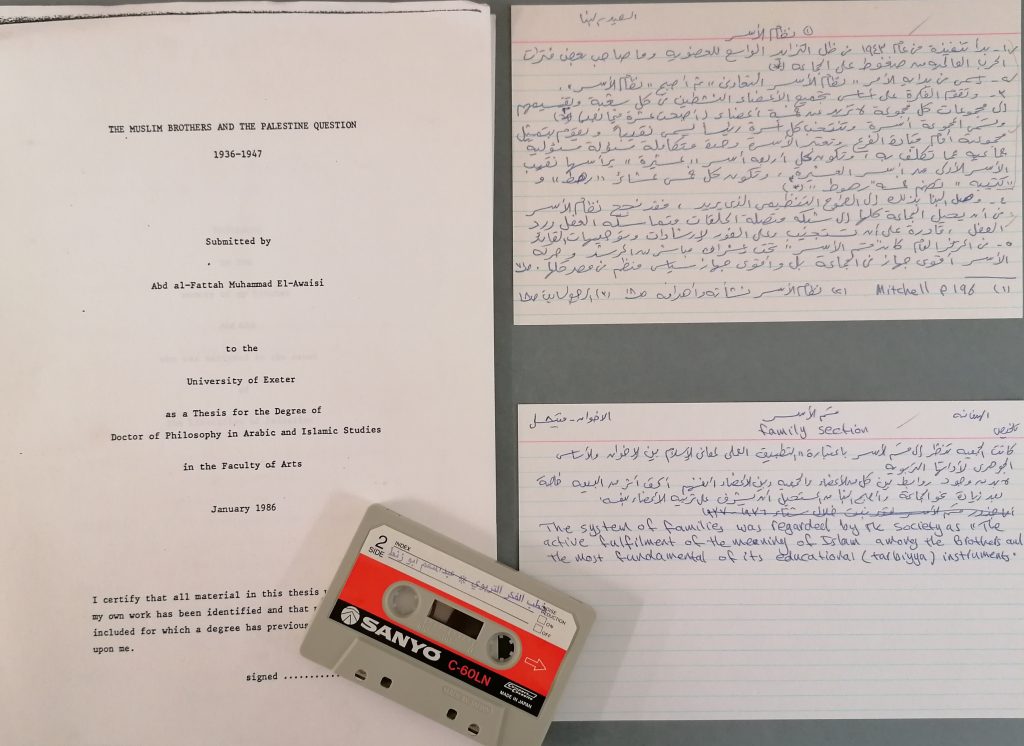

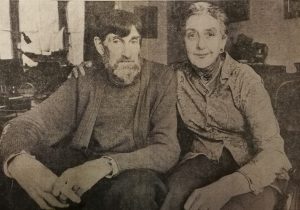

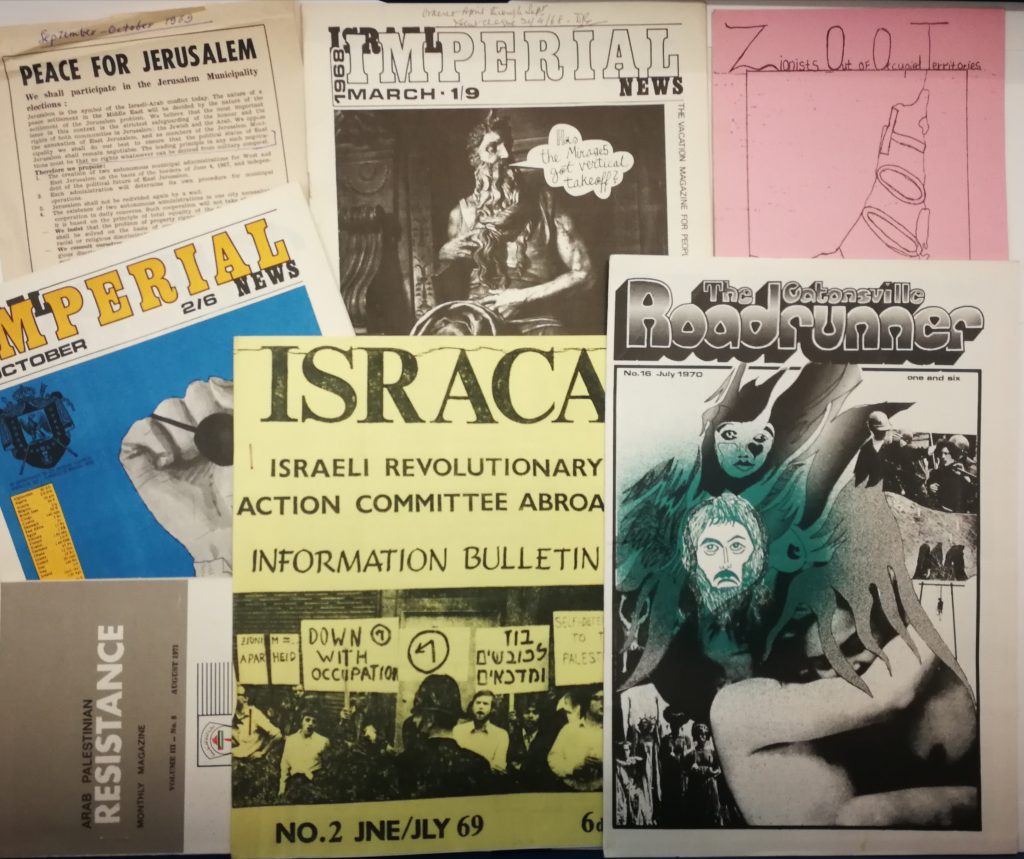

Ethel Edith Mannin (1900-84) was a prolific writer of novels and travel memoirs (many of which we have in our Hypatia collection), as well as a committed Socialist and political activist. She became interested in Palestine during period of the British Mandate, and was a staunch opponent of the Israeli occupation after 1948. Christopher Walker (1942-2017) was working in Sotheby’s department of historical and literary manuscripts when he came into contact with Mannin in the late 1960s through their shared interest in the Palestinian cause. They developed a strong friendship and corresponded regularly for several years, with their letters focussing primarily on Palestinian issues and the politics of the Middle East, Mannin sharing with the young historian her knowledge of people and places built up over decades of travel and political activism. We recently acquired a box of these letters, which have now been catalogued and make for fascinating reading, both for the insights into Mannin’s personality and relationship with Walker, and for what they reveal about Palestinian networks of resistance and communication during this period.

Mannin was born in Clapham in 1900, the eldest of three children of Robert Mannin, a postal worker, and a farmer’s daughter named Edith Gray. She began writing stories as a young girl, and was first published in The Lady’s Companion at the age of ten. When she left school she began working as a typist for Charles Higham’s advertising agency, and was soon promoted to copywriter and editor, as well as producing a monthly magazine called The Pelican in which she published her own articles and stories. In 1919 she married John Porteous, a manager at Higham’s thirty years her senior, and her only child Jean was born shortly after. They separated ten years later by which time Mannin had developed a deep interest in child care and education, especially in the progressive theories of A.S. Neill. She wrote several books on the topic, both novels and non-fiction. Indeed, this was the formula for her prolific output – to travel somewhere or research a subject, and then use the material as the basis for at least two books, one a non-fiction study and the other a novel.

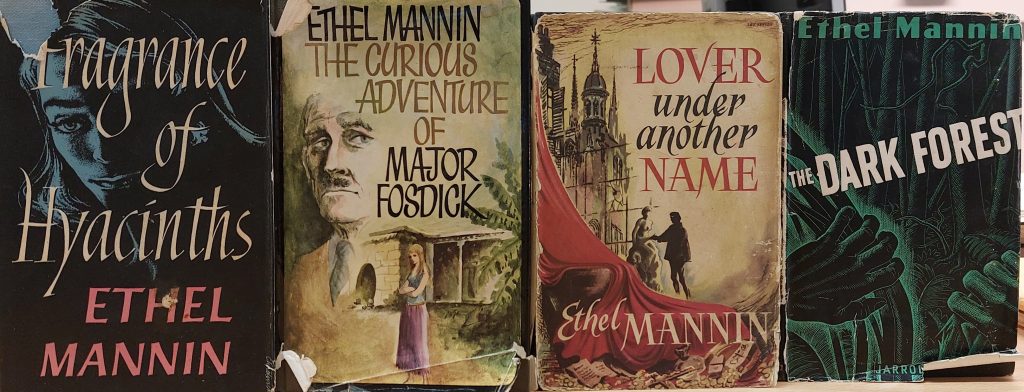

Some of Ethel Mannin’s novels in our Hypatia collection

By the time her marriage broke up she had published seven novels or anthologies, as well as numerous short stories, and was able to buy a house for herself and Jean: Oak Cottage, on Burghley Road in Wimbledon. Inside the ‘cottage’ was painted in riotous colours with a zig-zag patterned gramophone, reflecting Mannin’s modern personality and the zeitgeist of the Jazz Age. Her frank opinions on sexual education and women’s rights, as well as her affairs with celebrities such as W.B. Yeats and Bertrand Russell, earned her something of a reputation – and when she published the first of several volumes of autobiographical memoirs, Confessions and Impressions, in 1930, it proved a best-seller: it was reprinted fifty times over the next six years, and then republished in paperback by Penguin in 1937.

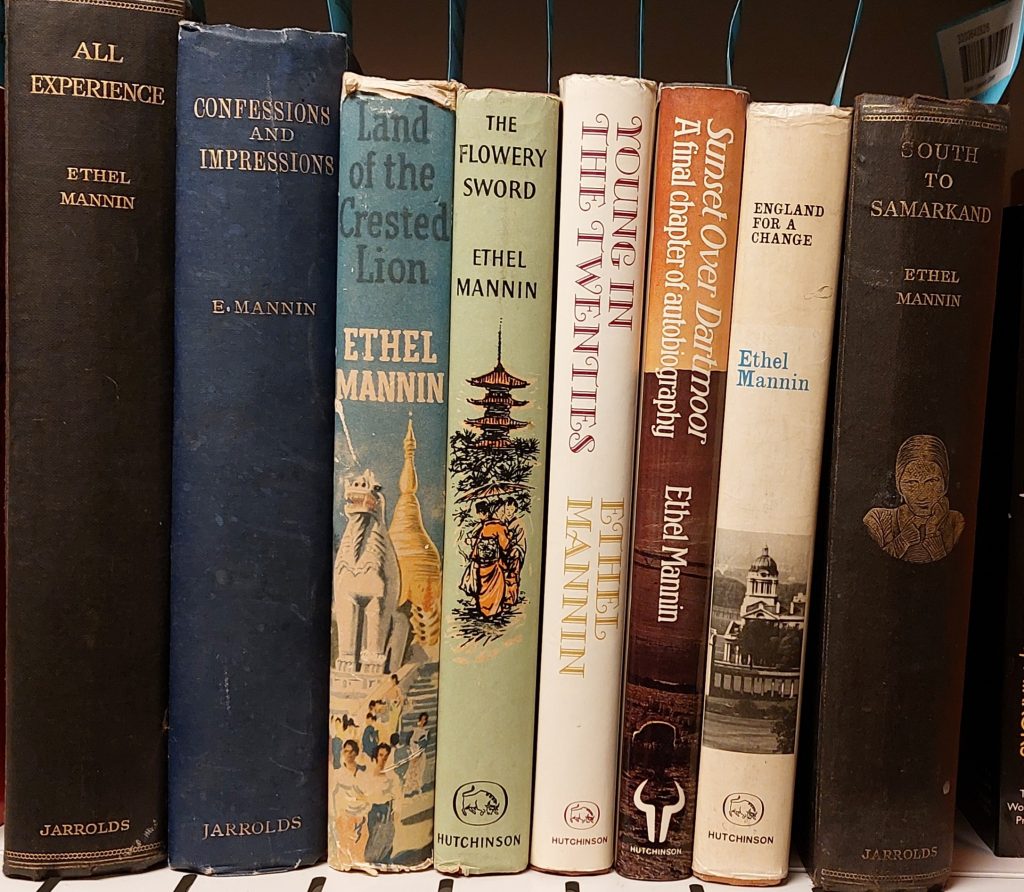

Ethel Mannin’s memoirs and travel writings in our Hypatia collection

If images of the Twenties suggest something of the frivolous ‘flapper’, it should be noted that Mannin was intensely interested in the political developments of the time and her writings took an increasingly strong left-wing bent by the early 1930s. Although initially a supporter of the Labour party, she became disenchanted with the failure of Ramsay Macdonald’s government to help the unemployed, and in 1933 she joined the Independent Labour Party (ILP) in 1933, becoming a frequent contributor to their newspaper, the New Leader. During the Spanish Civil War she was a committed supporter of the POUM (in Spanish, ‘Partido Obrero de Unificación Marxista’, or ‘Workers’ Party of Marxist Unification’), with which George Orwell fought in Catalonia. Upon his return, Orwell became a good friend of Mannin’s, as well as her second husband, the Quaker pacifist Reginald Reynolds (1905-58), whom she married in 1938. She dedicated Women and the Revolution (1938) to her friend Emma Goldman, a Russian-born anarchist who was deeply involved in the struggle against Fascism in Spain, and who provided the inspiration for Mannin’s novel Red Rose (1941).

Mannin’s engagement with Palestine also began in the 1930s, when Reynolds worked with Dr Izzat Tannous at the Arab Information Office in London. (Reynolds wrote about how he got involved in Palestine in his memoir My Life and Crimes, published in 1956.) Tannous, a Palestinian Christian who had qualified as a doctor in Lebanon, had been involved in the Arab nationalist movement during the Mandate period and would later be a founding member of the PLO in 1964. During the 1940s he had worked hard on negotiations with the British government to prevent the partition of Palestine. At first this was only part of her wider campaigning against imperialism, which included her collaborations with black activists such as C.L.R James and George Padmore during the 1930s, and her postwar protests against the British government’s oppression of Kenyan nationalists. However, her support for the Palestinian cause became a personal one following her visits to the Middle East in the early 1960s.

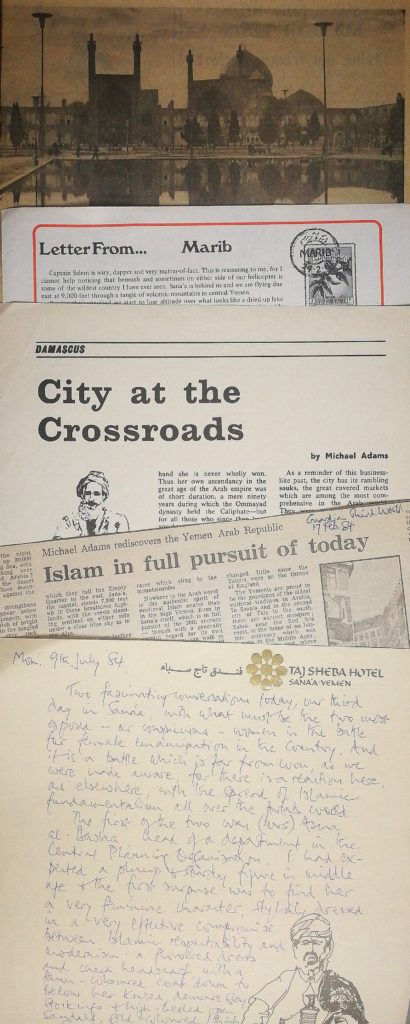

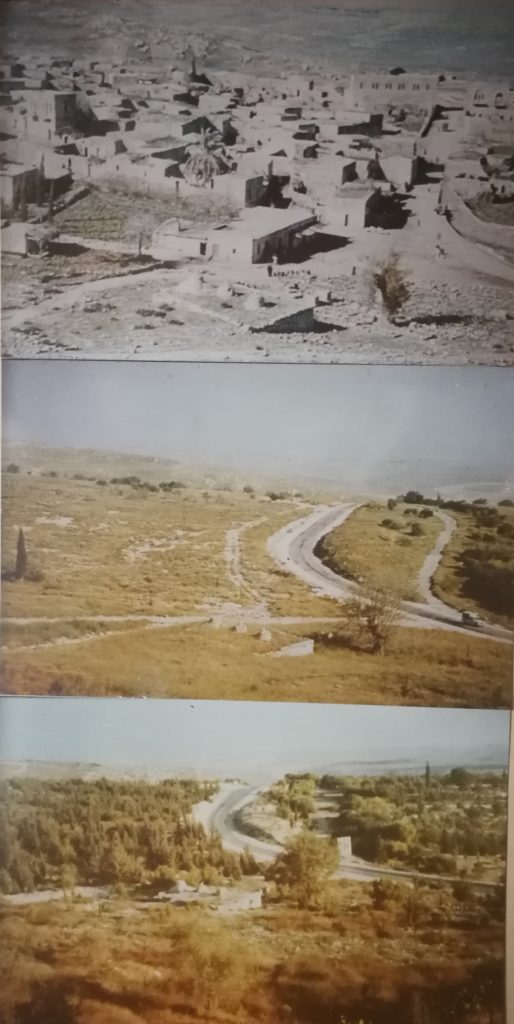

During her travels through Iraq and Kuwait, she met General Abd al-Karim Qasim, who had led the 1958 coup that ended the monarchy in Iraq. She formed a favourable impression of the General, who would be executed during the 1963 Ba’athist Coup, and made him a key character in her novel The Midnight Street (1969). There are photos of Mannin and Qasim together in her travelogue A Lance for the Arabs: A Middle East Journey (1963), which also recounts her sympathetic friendships with a number of Iraqi liberals such as student leader Khalid Ahmed Zaki. The novel that emerged from this visit, The Road to Beersheba (1963), she envisaged as a pro-Palestinian counterpoint to the international bestseller Exodus (1958), written by Leon Uris and presenting a heroic version of the founding of the state of Israel. In The Lovely Land (1965) and the chapter ‘Making a film with the Arabs’ in Stories from my Life (1973) she tells of the King of Jordan’s efforts to have the book adapted into a film. Although this plan eventually fell through, it was translated into Arabic, serialised on ‘Voice of the Arabs’ radio station and published in a Jordanian newspaper.

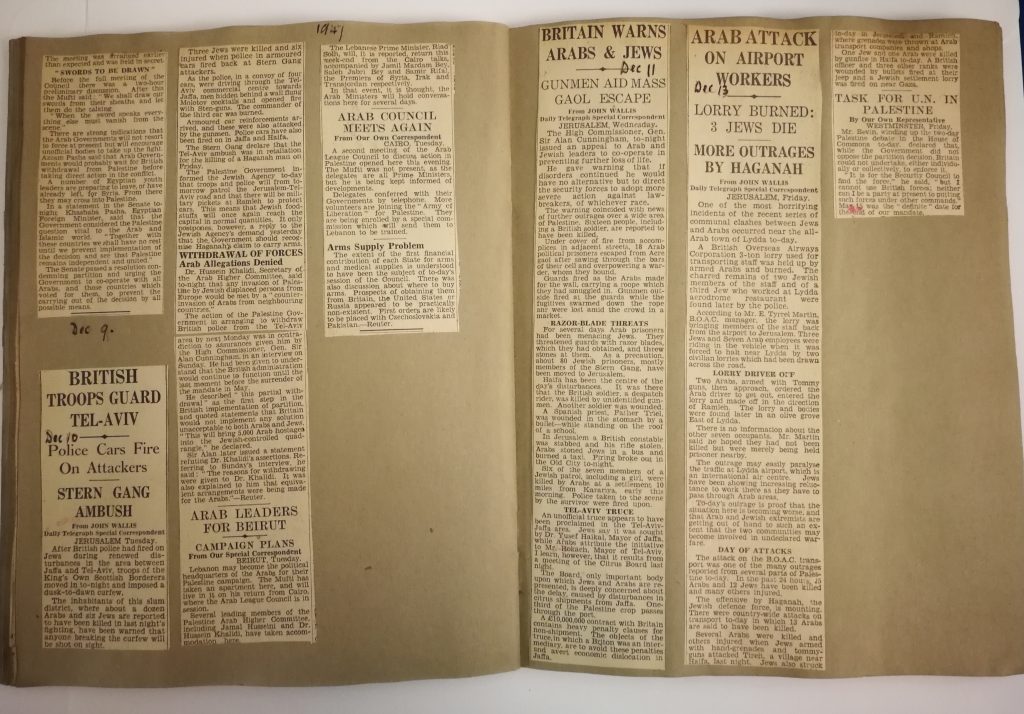

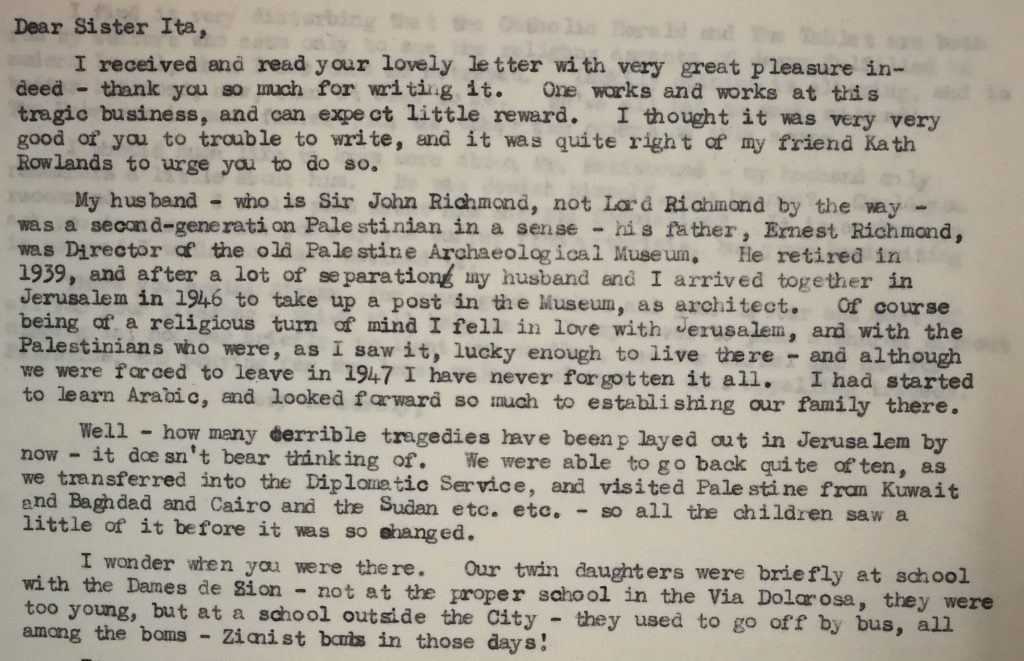

The Road to Beersheba tells the story of the Mansour family, who are violently evicted from their home in Lydda by Haganah militia in 1948 and forced into exile in Jordan. The young son Anton eventually comes to England where he meets other family members and Palestinian exiles. Some of their interactions – such as the scene where Anton’s mother tries to explain to a shopkeeper that her flowers ‘from Israel’ are actually from occupied Palestine – reflect arguments that were being made around the same time by Christopher Walker’s relative Lady Diana Richmond, an early member of CAABU and active campaigner for the Palestinian cause. Mannin’s letters contain numerous references to the Richmonds, as well as Michael Adams and other CAABU members, although she was critical of the organisation for its moderate stance regarding the State of Israel. (Mannin’s own views provide some intriguing insights into the tensions between left-wing politics, pacifism, pragmatic diplomacy and support for various revolutionary movements.) Other novels that focussed on the Palestine were The Night and its Homing (1966) – a sequel to The Road to Beersheba – and Bitter Babylon (1968).

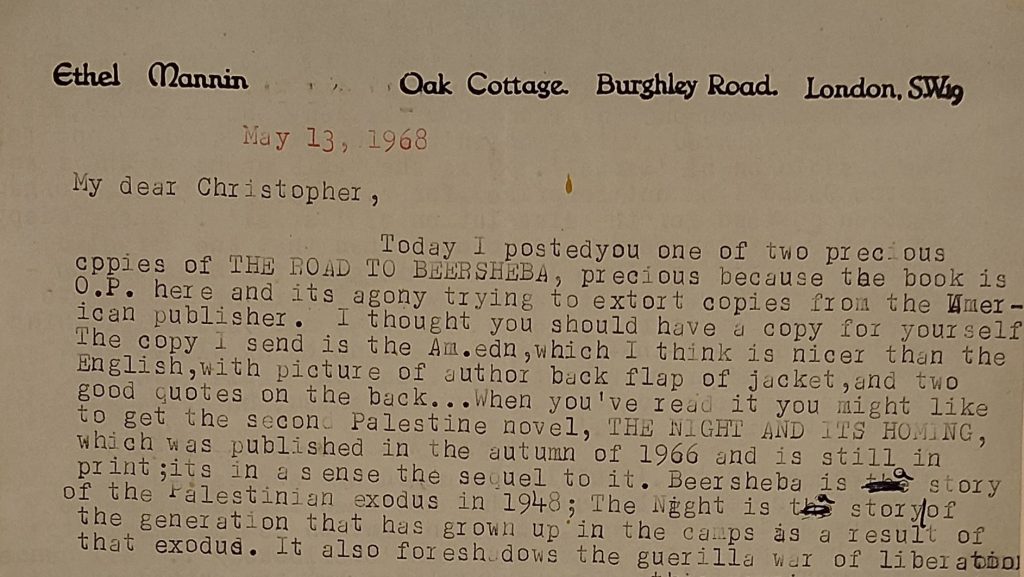

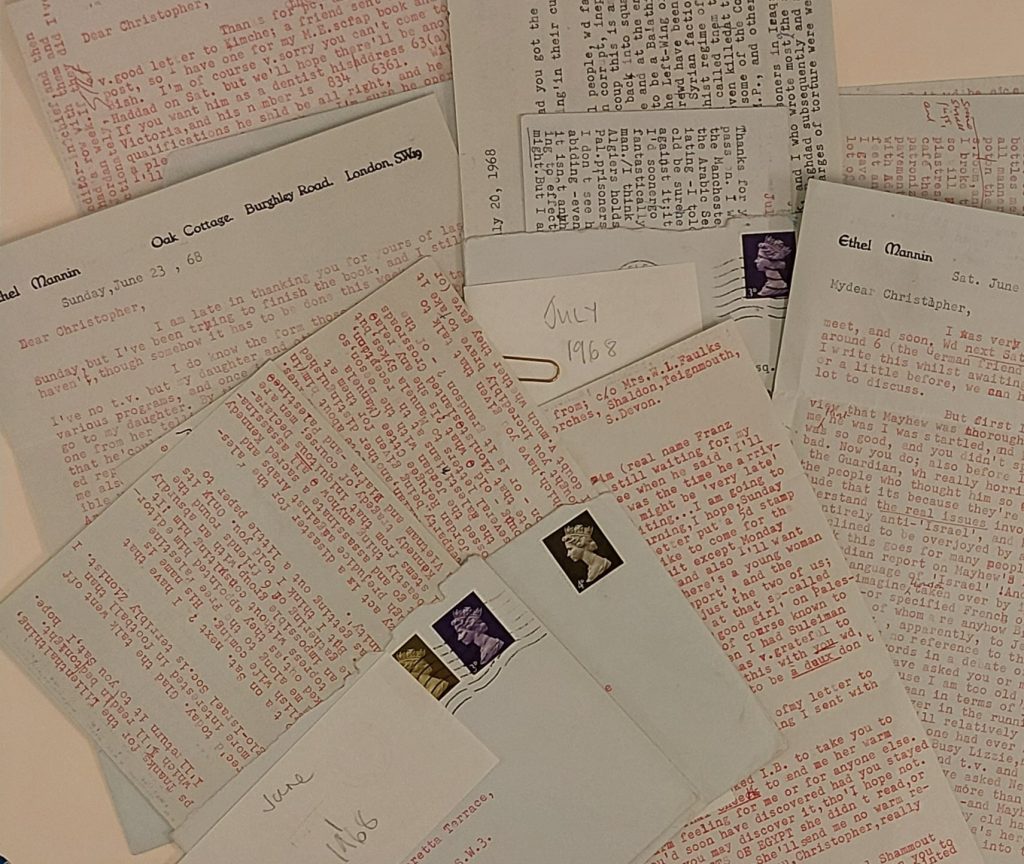

The letters to Walker begin in January 1968, with Mannin contacting him in response to a letter regarding Palestine he had written in The Times. She discussed her novels with him, often sending him copies of her own books and recommending the writings of some of her Palestinian friends. The letters contain many references to – and critical comments about – what was being published on Palestine, both in terms of articles and letters in the press, as well as books. She also comments on the quality of speakers at CAABU meetings, goings on at the Jordanian Embassy (to which she was occasionally invited for receptions) as well as the activities of various friends from Jordan and Palestine who came to her house for dinner. They are peppered with lively comments about people she had met in Palestine, Beirut, Iraq, Jordan and elsewhere in the Middle East, many of whom had become close friends and long-term correspondents. These references could be gossipy, affectionate, full of respect or savagely critical, but she provided Walker with personal introductions to many of her contacts in Palestine, Lebanon and Jordan, which would prove invaluable when the young historian travelled there in the summer of 1969. She also drew vivid pen portraits of many of those in the UK who were involved in media or academic work relating to Palestine, some of whom she met at Committee meetings or public lectures. Names mentioned in her letters include her longstanding friend Rev. Eric Bishop (1891-1980), an ‘old Palestinian hand’ and member of the Church Missionary Society who held Arabic services in London, Musa Alami, Basil Aql, Moshe Menuhin, Musa Mazzawi, Rouhi Khatib – former Mayor of Jerusalem – Suleiman Mousa, Desmond Stewart, Anthony Nutting, Christopher Mayhew, Manuela Sykes, Elizabeth Collard, John Reddaway, Peter Mansfield, John Richmond and Michael Adams, Faris Glubb and his father John Bagot Glubb, Ismael Shammout, Izzat Tannous, Basil Ennab, Jordanian Ambassador Anwar Bey Nuseibeh, Adel Jarrah (Charge d’Affaires at the Kuwait Embassy), Dr. Anis Sayegh and Fayez Sayegh, Egyptian artist Youssef Francis, Fareed Jafri, and Soraya ‘Tutu’ Antonius, with whom she danced ‘the twist’ in Beirut in 1962. (Soraya was the daughter of Lebanese intellectual and Arab nationalist George Antonius, author of The Arab Awakening (1938). There are letters from both Soraya [‘Thurayya’, hence ‘Tutu’] and her mother Katy Antonius in the Richmond archive, EUL MS 115.)

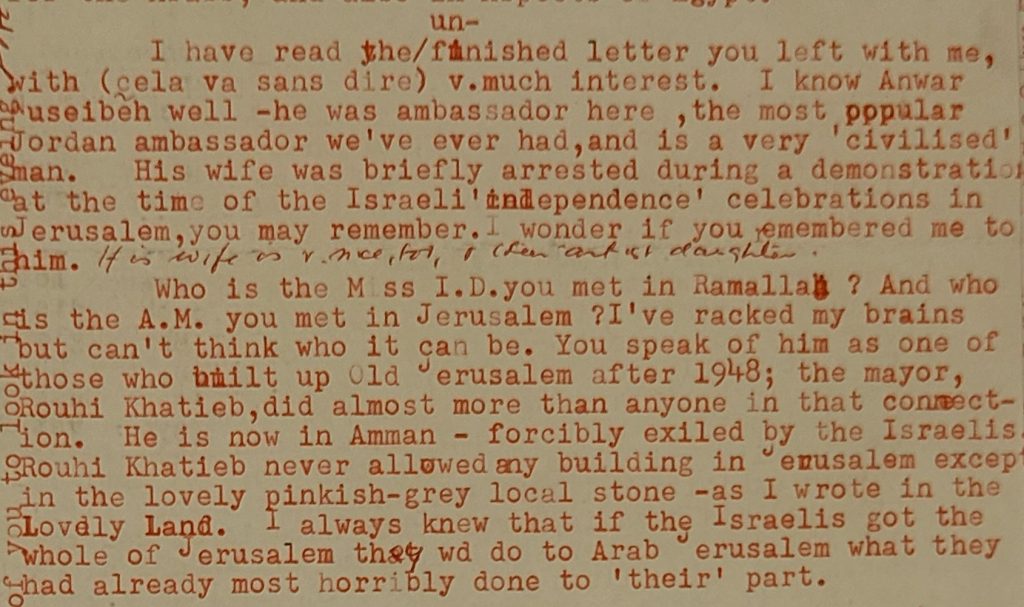

A sample excerpt from one of Mannin’s typed letters, often annotated with additional lines typed around the edges

By this time she was of course almost seventy years old, and admitted frankly to Walker that she found social activities a tiresome chore and really wanted peace to work on her writing, for which she relied in order to make a living. In a letter of 19 September 1970 she told Walker that by the time of her 70th birthday she hoped ‘to bring her annual income up to that of a dustman.’

Over the next few years she managed to finish off various autobiographical writings, some of them charting her travels around England, including England at Large (1970), Free Pass to Nowhere (1970), My Cat Sammy (1971), England My Adventure (1972) and Stories from My Life (1973), as well as what would be her final novel with a Middle East setting – Mission to Beirut (1973), about the murder of a diplomat. She revealed in a letter of 27 January 1972 that the plot was inspired by the ‘inside story’ of the assassination of Jordanian Prime Minister Wasfi Tal a few weeks earlier. As she had not visited Beirut since 1962 she asked Walker to fill her in on some of the recent changes to the city, so that she could ensure the details were all authentic.

In September 1974 she sold Oak Cottage and moved to Overhill, a house in Brook Lane, Shaldon, near Teignmouth in Devon, to be with her daughter. (Jean had married Leslie Faulks, who developed cancer around 1970; they had a daughter named Catherine.) Mannin had a sister in Exeter but they seem to have had little contact. Around this time she and Walker appear to have lost touch, with their letters ceasing in 1976. In their 1972 correspondence they discussed the work he was beginning on writing a book about Armenia, a task that would take him the next eight years. Armenia: survival of a nation was finally published by Croom Helm in 1980. In the meantime, Mannin had finished her final book, an autobiographical memoir entitled Sunset over Dartmoor (1977) which contains two chapters about the Middle East: Chapter 13 ‘Some reflections on Palestine’ and Chapter 14 ‘The Time of My Life’, which recounts highlights and thoughts about her travels to Palestine, Jordan, Egypt and Syria between 1962 and 1966. Her letters to Walker have a similar valedictory feel at this time, as she reflects upon her retirement, how she was no longer in touch with any of her Middle East contacts, and her feelings about her fifty years of involvement in the Palestinian struggle. ‘Being now 80,’ she wrote, ‘I will hardly live to see Palestine liberated – but YOU may, and probably will. Drink a toast to me then, and to all the old campaigners…’

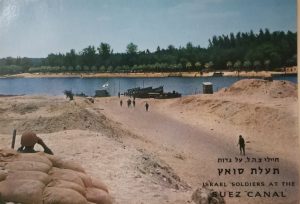

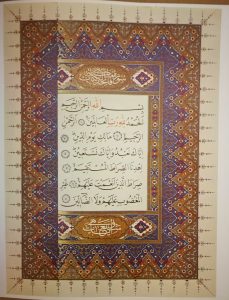

Mannin died four years after her last letter to Walker, who continued to study and lecture on the subject of Armenia. His research on the role of religion in the Ottoman Empire developed into a more comprehensive analysis of the relationship between Islam and the West, which provided the focus for various talks and publications in the 2000s. His Islam and the West: A Dissonant Harmony of Civilizations (Stroud: Sutton, 2005) refuted the ‘clash of civilisations’ narrative that had grown popular around this time, arguing instead that much of the current tension was a result of the west having forgotten its long history of interaction with the Islamic east, the richness of their intellectual and commercial exchanges over many centuries, and the mutual respect and tolerance that had characterised these relationships. He died in 2017, without having seen the liberation of Palestine.

This collection of correspondence supplements other letters from Mannin that we hold in our collections, including those among the papers of Henry Williamson (EUL MS 43) and Malcolm Elwin (EUL MS 423). It also complements other Middle East archives – Christopher Walker’s uncle was Sir John Richmond, and there are numerous references to CAABU and mutual acquaintances in both the Richmond archive (EUL MS 115) and the papers of Michael Adams (EUL MS 241). We have over thirty of Mannin’s novels in the Hypatia Collection too, and the letters between her and Walker could make for a fascinating research project for anyone seeking to explore Mannin’s views and activities supporting Palestinian resistance, the relationship between her literary work and political engagement, British networks of pro- and anti-Zionist advocacy, the interaction between British leftwing politics and support for Palestine (a topic that continues to provoke contentious discussion within the Labour Party) or simply to gain a greater knowledge of the literary and academic circles of the period. Catalogue entries for the correspondence can be found here.

Further Reading

By Ethel Mannin –

Middle East novels:

The Road to Beersheba (London: Hutchinson, 1963)

Bitter Babylon (London: Hutchinson, 1968)

The Midnight Street (London: Hutchinson, 1969)

Mission to Beirut (London: Hutchinson, 1973)

Travel writing:

Moroccan Mosaic (London: Jarrolds, 1953)

A Lance for the Arabs: A Middle East Journey (London: Hutchinson, 1963)

Aspects of Egypt (London: Hutchinson, 1964)

The Lovely Land. The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan (London: Hutchinson, 1965)

By Christopher Walker –

The Armenians (Minority Rights Group Report No.32, 1975), co-authored with Professor David Marshall Lang

Armenia: The Survival of a Nation (Croom Helm, 1980)

Armenia and Karabagh: the struggle for unity (Minority Rights Group, 1991) – editor

Oliver Baldwin: A Life of Dissent (London: Arcadia, 2003)

Visions of Ararat: writings on Armenia (Continuum, 2005)

Islam and the West: A Dissonant Harmony of Civilizations (Stroud: Sutton, 2005)

‘Friends or Foes? The Islamic East and the West’, History Today Volume: 57:3 (Mar 2007) pp.50-7

Other

Sarah Graham Brown, ‘A Lance for the Arabs: Ethel Mannin’, The Middle East No.125 (March 1985) p.62.

Ahmed Al Rawi, ‘The post-colonial novels of Desmond Stewart and Ethel Mannin’, Contemporary Arab Affairs Vol.9:4 (2016) pp.552-64.

Caroline Rooney, ‘The First nakba Novel? on Standing with Palestine,’

Interventions. International Journey of Postcolonial Studies, Vol. 20:1 (2018) pp.80-99.

Christopher J. Walker, Armenia: the survival of a nation (London: Croom Helm, 1980)

Rebecca Jinks, The Uncompromising Facts Of History: Christopher J. Walker’s Writings On Armenia (2021)

Philipp Winkler, ‘Che Guevara of the Middle East’: Remembering Khalid Ahmad Zaki’s Revolutionary Struggle in Iraq’s Southern Marshes’, in The Arab Lefts: Histories and Legacies, 1950s–1970s (Edinburgh University Press, 2020) pp.207-221. [Article on Mannin’s friend, whose death is referred to several times in her letters to Walker.]