This year, in collaboration with the Section 28 and Its Afterlives project, Special Collections was pleased to welcome Chloë Edwards on an internship to explore student publications in the University Archive to find out what they can tell us about LGBTQ+ lives and the impact of Section 28 at the University. Below, Chloë shares her findings.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The Background of the Project

I was delighted to be offered an archival internship with the Section 28 and Its Afterlives project team and the University Library’s Special Collections. Section 28 of the Local Government Act, in place from 1988 until 2000 in Scotland, and until 2003 in England and Wales, prohibited local authorities from “promoting homosexuality” as a “pretended family relationship”. This National Lottery Heritage funded project explores the impact of Section 28 and its consequences on local lives in the South West.

My role involved searching for articles and discussions pertaining to Section 28 in Exeter’s student publications, a task which had struck a chord with me for several reasons. Firstly, owing to its proximity to my ongoing PhD research for my thesis entitled Listen Without Prejudice: Queer Masculinities in the Popular Music Cultures of Thatcher’s Britain. Secondly, as a woman from Cardiff, I am always supportive of projects unearthing LGBTQ+ histories and experiences beyond the largest urban spaces across the nation. Lastly, I happened to write and edit articles for Exeter’s current student publication, Exeposé, for two years as an undergraduate. Collectively, as a result, I was eager to begin poring over back issues of Exeposé and its predecessors, as valued records of the lives and concerns of local undergraduates who have progressed through the university.

After discussion with the Section 28 and Its Afterlives team and Special Collections archivist Annie Price, I began my research into Exeter’s student newspapers. We had decided to begin my research at the point at which the Sexual Offences Act 1967 partially decriminalised sex between men over the age of 21 in England and Wales. This origin point meant that I could begin my research with a thorough overview of the documentation of attitudes and legislative changes to gay and queer lives in the UK leading up to the enactment of Section 28 in 1988.

The Early Thatcher Years & Gay Lives on Campus

The South Westerner was the chief campus paper at the time of the Sexual Offences Act’s passing in 1967. Running up until 1979, the year in which Margaret Thatcher was elected prime minister, several articles and excerpts reflect the atmosphere and attitudes of Exeter’s students to LGBTQ+ lives and rights in the years following the legislative change. Initially, letters and articles covered the tearing down of GaySoc posters around campus; gradually, there appears to be an ongoing shift in willingness to discuss and support gay students in Exeter. GaySoc, an ancestor to the current University of Exeter LGBTQ+ Society, was increasingly active in these years, organising events around the university and city in a move towards community building, seen in an advert for a former club near the Quay that hosted a bespoke disco night (fig. 1).

Figure 1: Routes Advert, The South Westerner, 22 February 1979, p. 3, Exeter University Special Collections, Exeter University/SOU, South Westerner 1978-1980 (accessed 21st February 2024).

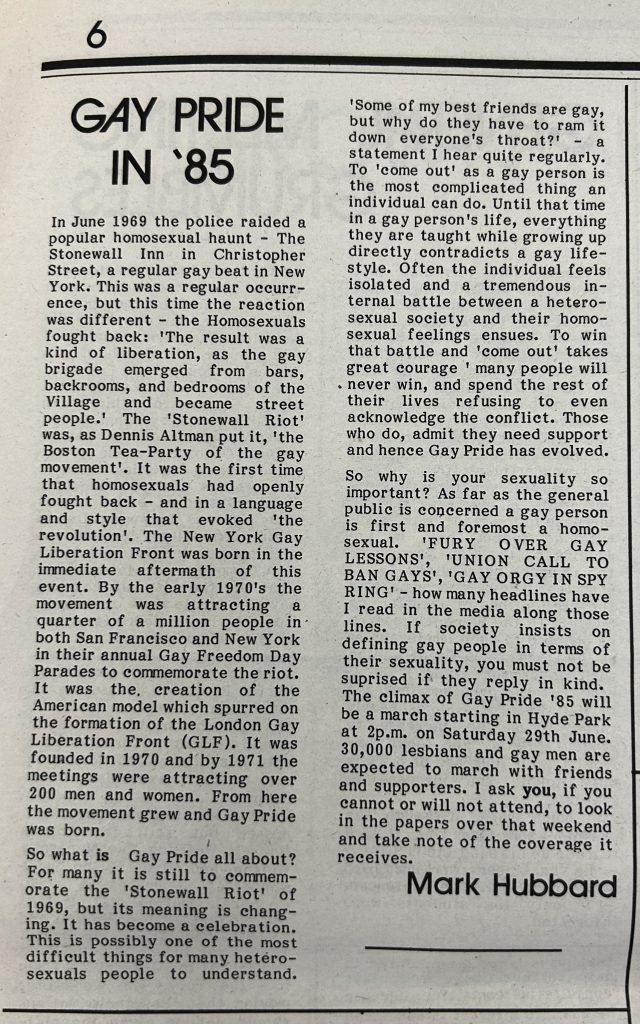

Figure 2: Mark Hubbard, ‘Gay Pride in ‘85’, Signature, Summer 1985, p. 6, Exeter University Special Collections, Exeter University/SIG, Signature 1983-85 (accessed 27th February 2024).’

A few years after the last issue of The South Westerner was published, its successor Signature debuted on campus in 1983. As the Thatcher years progress, the paper includes more features with members of GaySoc, as well as features around London Pride in 1985 (fig. 2), and growing awareness surrounding the ongoing HIV/AIDS epidemic, including a cover feature from December 1986, which, notably, preceded the government’s own public information campaign

in 1987.

in 1987.

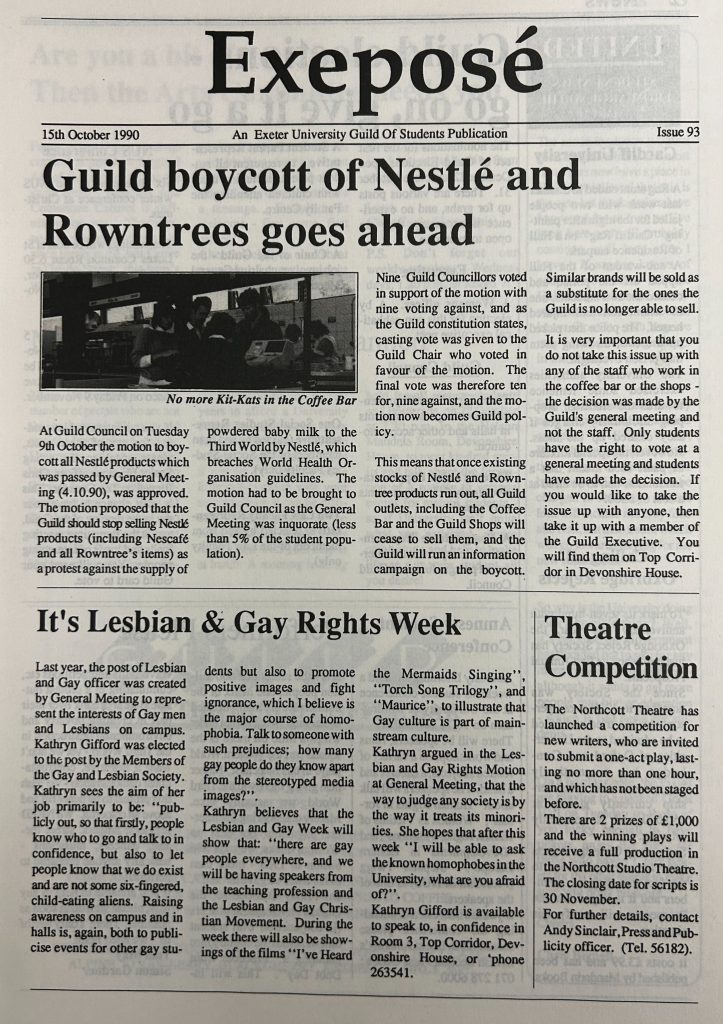

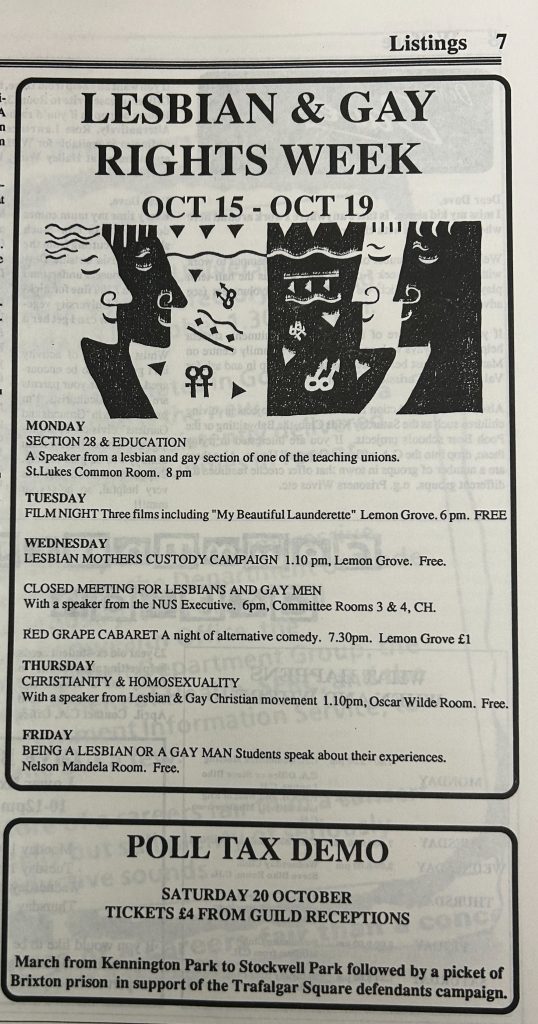

Section 28 and Exeposé

Following the passing of Section 28 in 1988, the early issues of the university’s current student publication, Exeposé, reveal a pivotal decade in which LGBTQ+ visibility grows even as it is being legislated against. GaySoc evolves into Lesbian, Gay and Bisexual Society, and the Guild comes to include both the elected position of Lesbian and Gay Rights Officer and an annual Lesbian and Gay Rights Week. For 1990’s Lesbian and Gay Rights Week, Exeposé listed the events planned by the Lesbian and Gay Officer as a cover feature. Alongside film screenings, the Week included a talk on Section 28 and education, highlighting the concern of students about the law and their university teaching (figs. 3 and 4). Notably, in figure 4, the placement of the week’s events also advertises a demonstration against the proposed Poll Tax of 1990, indicating the socio-political issues on the minds of Exeter’s students at this point.

Unknown, ‘Cover – It’s Lesbian and Gay Rights Week, Exeposé, 15th October 1990, p. 1, Exeter University Special Collections, Exeter University/EXEPOSE, Exeposé, 1990-1993 (accessed 19th March 2024).

Figure 4: Unknown, ‘Listings – Lesbian and Gay Rights Week’, Exeposé, 15th October 1990, p. 1, Exeter University Special Collections, Exeter University/EXEPOSE, Exeposé, 1990-1993 (accessed 19th March 2024).

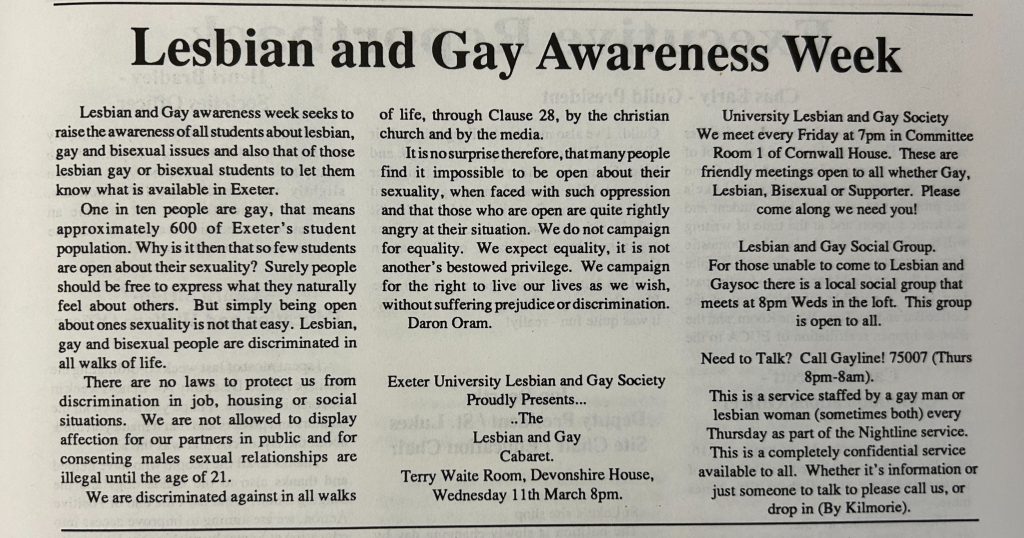

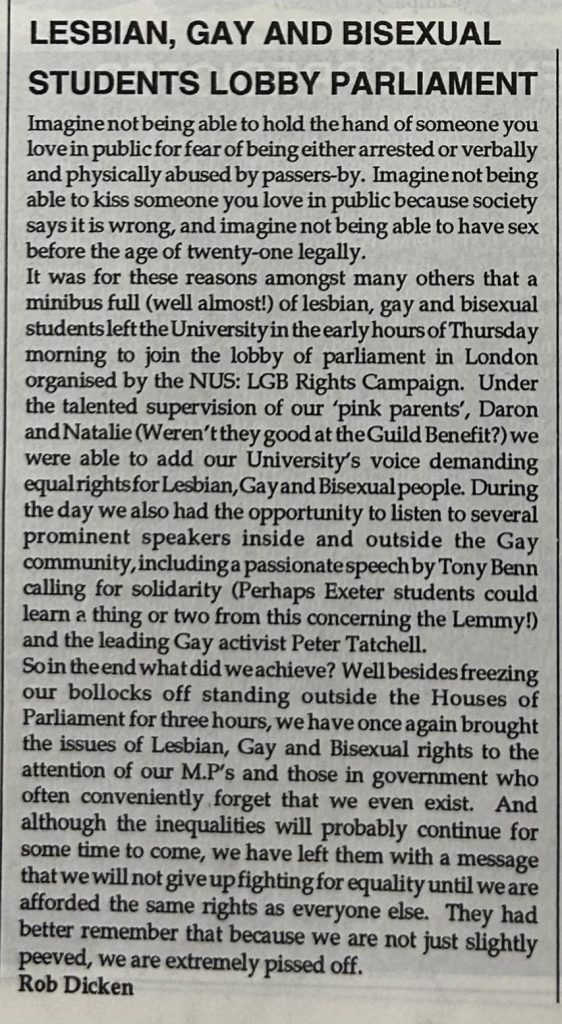

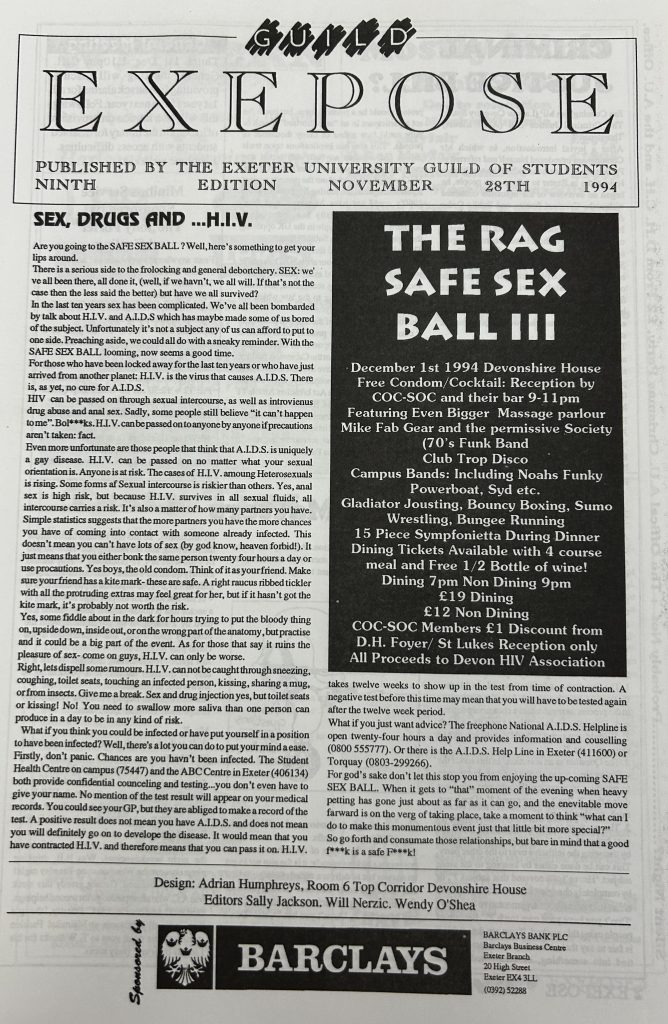

The following year’s Lesbian and Gay Rights Awareness Week was covered in Exeposé with an article outlining its significance in the context of the restrictions of Section 28 and its impact (fig. 5). Throughout the 1990s, several recurring names within articles ensured that the frustration and inequality brought about by Section 28 was not forgotten. In 1993, lesbian, gay and bisexual students lobbied Parliament in a protest that made front-page news on the subsequent issue of Exeposé (fig. 6) and joined a candle-lit vigil in London urging the government to reduce the age of consent for gay men. A specific weekly Nightline evening for queer students also sought to provide a local helpline for Exeter’s students. By this point, too, it appears that the Safe Sex Ball was an event held on 1st December, World AIDS Day, with proceeds going to local charities such as the Devon HIV Association (fig. 7).

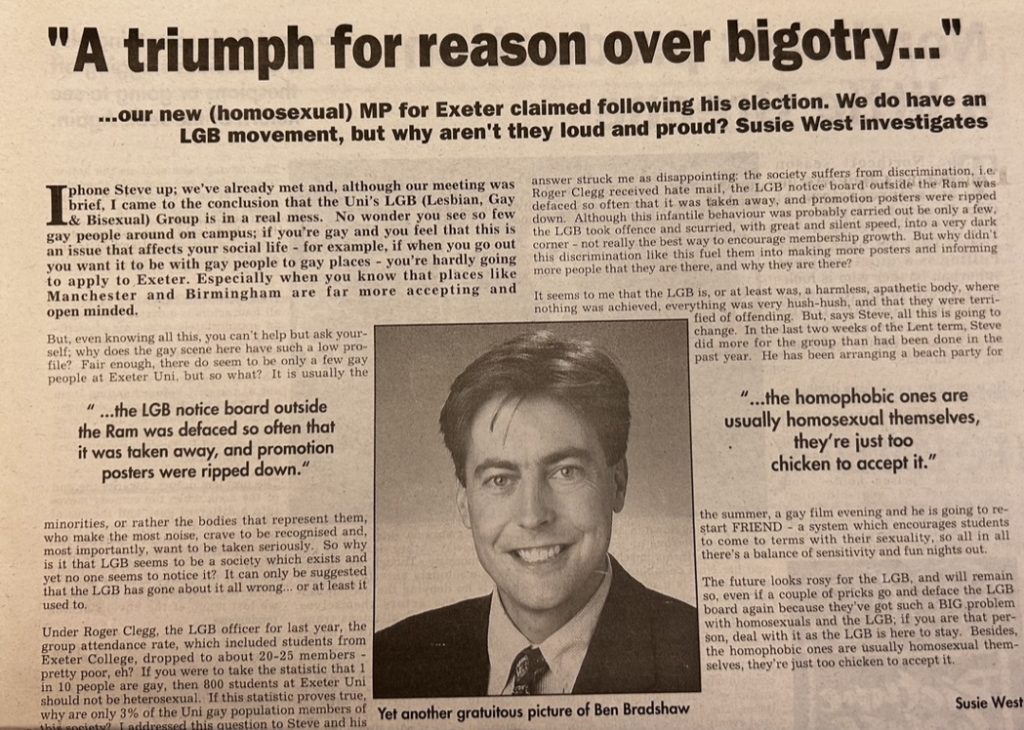

In the wider Exeter area, the 1997 General Election indicated a significant shift in attitudes evident in the articles published in student newspapers just a few decades prior. The election of the current Exeter Labour MP, Ben Bradshaw, was recorded as a victory over “bigotry”, and, as seen in figure 8, an Exeposé interview with Bradshaw offered a moment of reflection on the landscape of LGBTQ+ rights towards the end of the twentieth century.

Figure 5: Daron Oram, ‘Lesbian and Gay Awareness Week’, Exeposé, March 1991, n. pag., Exeter University Special Collections, Exeter University/EXEPOSE, Exeposé, 1990-1993 (accessed 20th March 2024).

Figure 6: Rob Dicken, ‘Lesbian, Gay and Bisexual Students Lobby Parliament’, Exeposé, 1st March 1993, p. 1, Exeter University Special Collections, Exeter University/EXEPOSE, Exeposé, 1990-1993 (accessed 20th March 2024).

Figure 7: Unknown, ‘Sex, Drugs, and HIV’, Exeposé, 28th November 1994, p. 1, Exeter University Special Collections, Exeter University/EXEPOSE, Exeposé 1994-1996 (accessed 25th March 2024).

Figure 8: Susie West, ‘A triumph for reason over bigotry’, Exeposé,12th May – 25th May 1997, p. 3, Exeter University Special Collections, Exeter University/EXEPOSE, Exeposé 1996-1998 (accessed 26th March 2024).

Only in 2003 was Section 28 fully repealed, with its ripples palpable long after its scrapping. The student publications held in the Special Collections on campus offer a vivid, important record of the effects of the changing landscape of LGBTQ+ lives and rights in the local area, and those at the university who were campaigning for equality, acceptance, and action within some of the darkest moments of recent national queer history. The papers allow us to see changes within the community as well, as GaySoc grew into the Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Society by the 1990s, and ultimately into the LGBTQ+ Society that is with us today.

By Chloë Edwards (pronouns: she/her/hers)

Doctoral Researcher (Art History & Visual Culture)

Postgraduate Teaching Associate

Research Culture Assistant, HASS PGR Gender & Sexuality Research Network

Faculty of Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences, University of Exeter

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The Section 28 and its afterlives project is co-led by Helen Birkett, Chris Sandal-Wilson, and Hannah Young in the Department of Archaeology and History at the University of Exeter. As well as supporting archival research into the South West’s LGBTQ+ history, the project team are conducting oral histories with LGBTQ+ people in the South West across 2024 with support from the National Lottery Heritage Fund. You can find out more about the project, including how to share your own stories of Section 28, here.

If you are interested in exploring LGBTQ+ history, you can find out more about resources in the University of Exeter’s Heritage Collections in the LGBTQ+ Research Resources guide.