Although Exeter is not renowned for its African collections, there is some valuable material here. Our Middle East archives and AWDU collections include extensive material from Egypt and Sudan, with a range of items from other North African countries including Libya, Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia. As a member of SCOLMA, the UK Libraries and Archives Group on Africa, Exeter also specialises in material on Ghana, and the ‘Ghana Collection’ housed in the Old Library, has thousands of books, official documents, microfilms and pamphlets. However, we also have a unique and fascinating archive in Special Collections that documents the work of Jean Trevor with Hausa girls and young women in northern Nigeria.

Jean Trevor (1931-75)

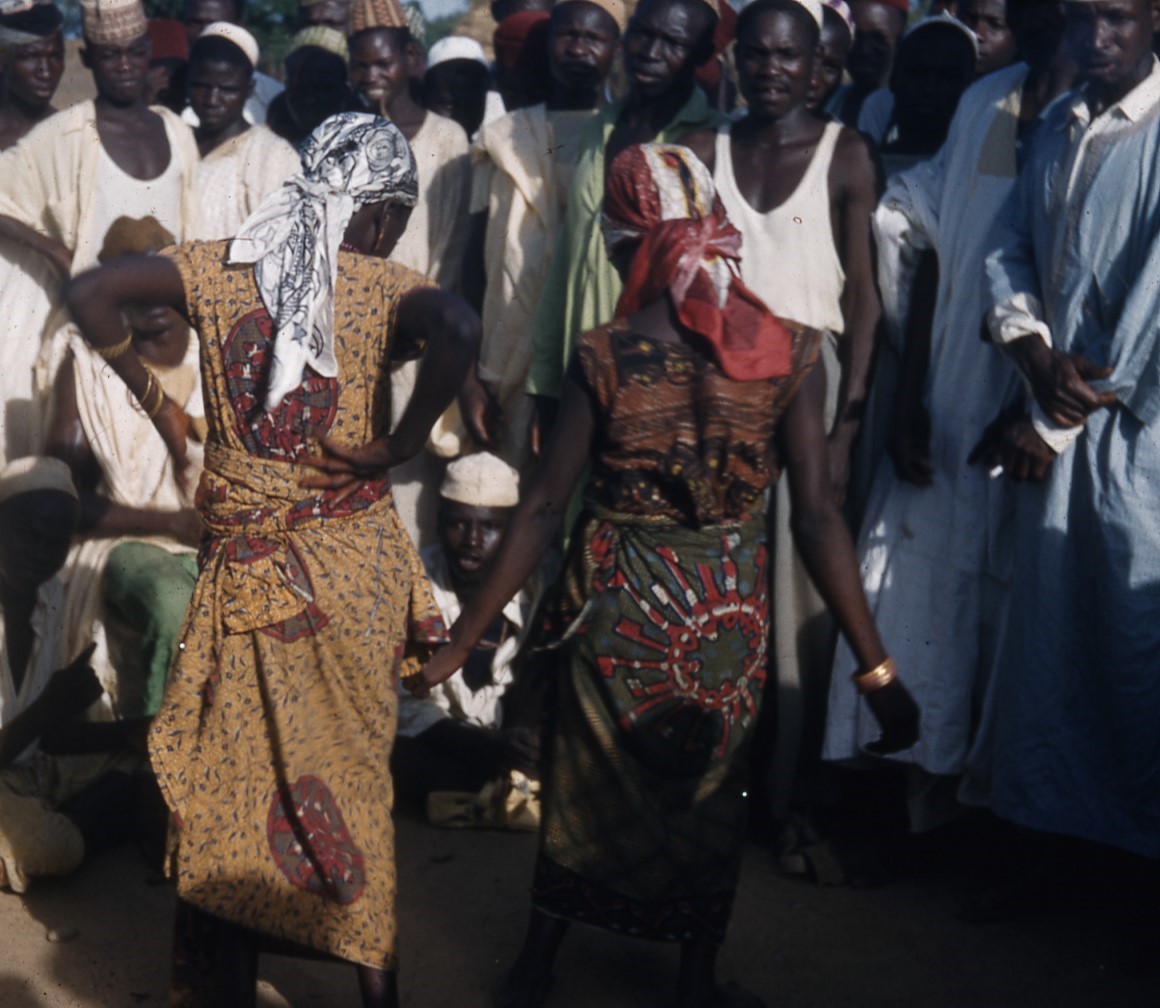

Jean Felicity Cole was born in Bodmin, Cornwall, on 20 April 1931. After completing school she studied for a sociology degree at LSE before going out to teach in northern Nigeria in 1953. Over the next few years she taught in different schools in northern Nigeria, mostly in the Hausa language which is spoken by millions of people in this part of the country, as well as in other countries such as Ghana and Cameroon. In Nigeria, it was spoken by the closely-related Hausa and Fulani tribes, and having learned the language, Jean was able not only to teach but also to converse with local families and develop a deeper understanding of their social lives and aspirations

For the first two years or so she was based in a Girls’ School in Sokoto, also known as ‘the City of Shaihu and Bello.’ This is a reference to the founder of the Sokoto Caliphate, Shehu Usman dan Fodio (1754-1817), and his son Muhammadu Bello (1781-1837) who succeeded him as Second Caliph.

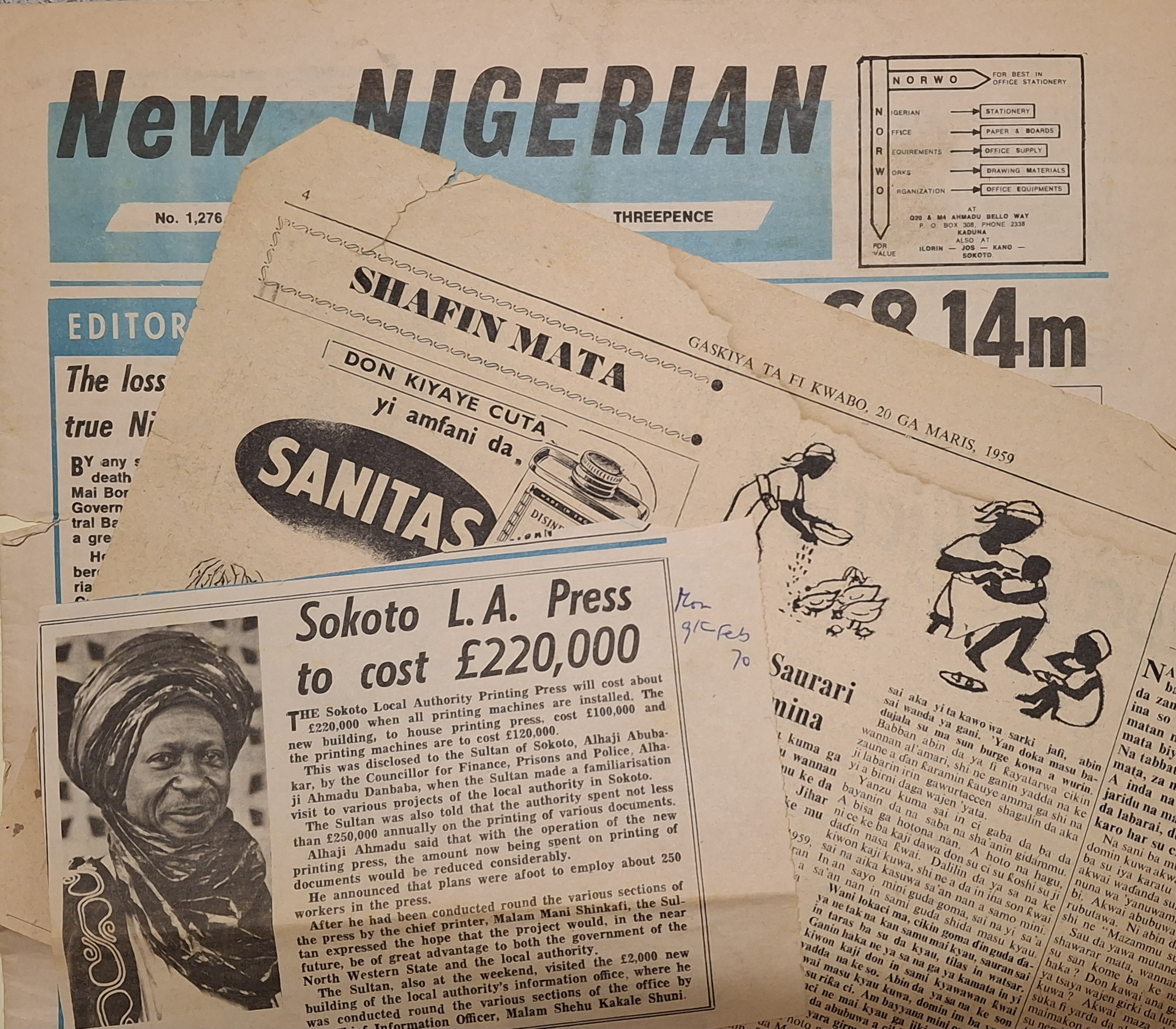

In Jean’s time, the Caliphate was ruled by Siddiq Abubakar III (1903-88), a direct descendant of Dan Fodio. He became 17th Sultan of Sokoto in 1938 and reigned for fifty years, until his death in 1988. George VI awarded him a KBE in 1944, and after Nigeria attained independence in 1960, he was made a Grand Commander of the Order of the Niger (GCON) by the Federal Republic of Nigeria in 1964. He was a supporter and government colleague of Sir Ahmadu Bello GCON KBE (1910-66), who was also descended from Dan Fodio. A photograph of him appears in the newspaper cutting above.

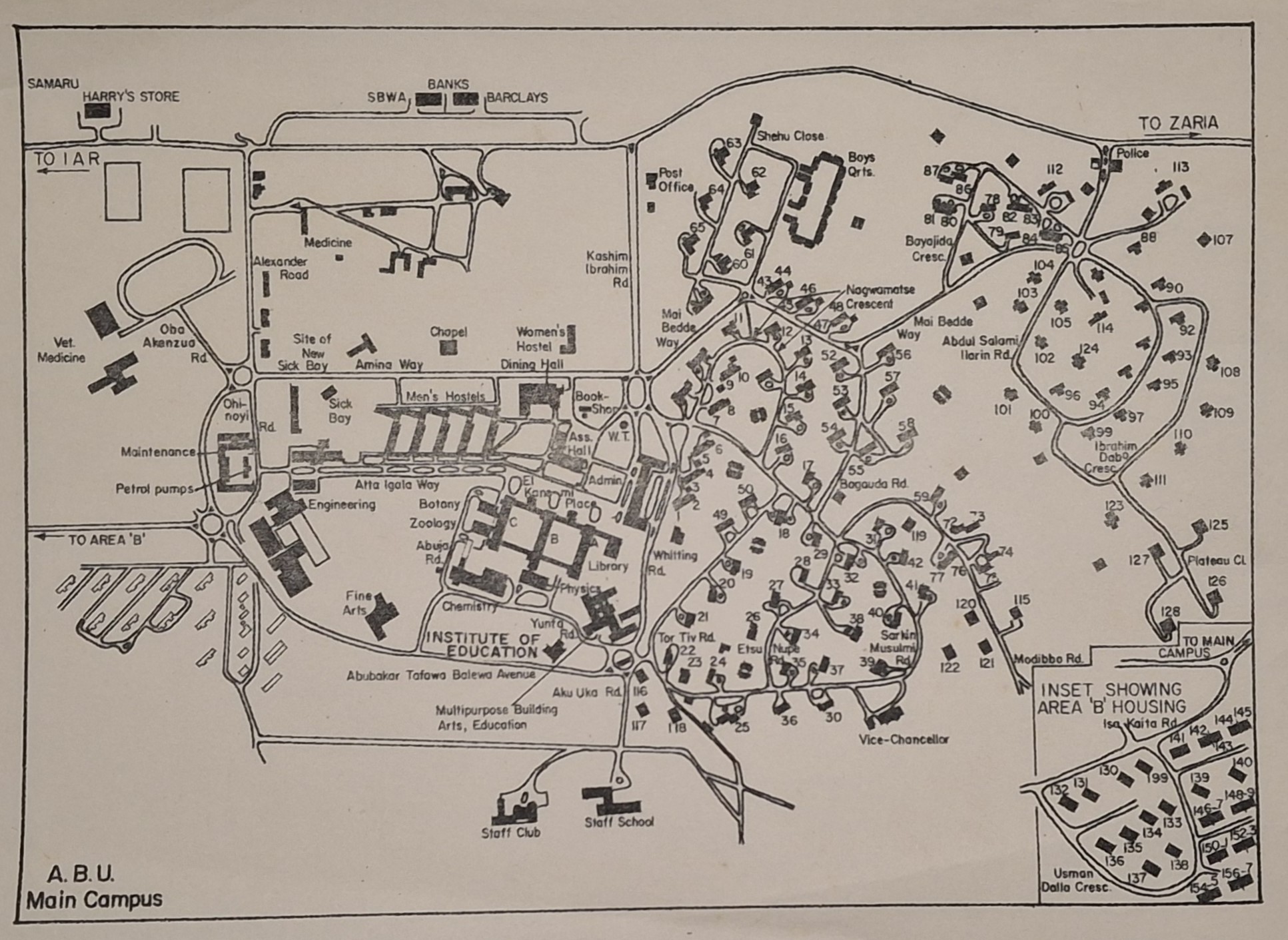

Ahmadu Bello University – where Jean later did her PhD – was founded in 1961, bringing together the School of Arabic Studies in Kano with the Nigerian College of Arts, Science and Technology, and the Agricultural Research Institute (both of which were at Samaru) along with the Institute of Administration at Zaria, and the Veterinary Research Institute at Vom. The new university was based at Zaria, some 400 km SE of Sokoto.

Marriage and Family Life

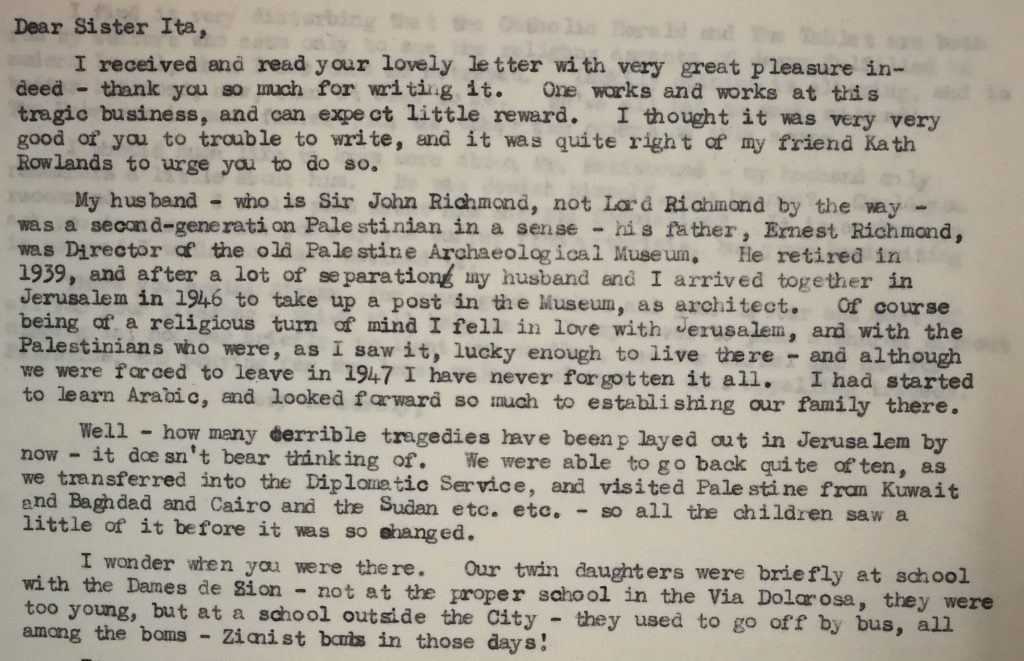

While in Nigeria she met Arthur Henry Tudor Trevor (1920-2003), son of the former Political Resident in the Persian Gulf, Lt. Col. Arthur P. Trevor ICS (1872-1930), who was then working in agricultural development. They married on Christmas Eve 1957 in Maiduguri, capital of Borno State, in NE Nigeria.

Much of her time over the next few years was spent raising her two sons, David (born in 1958) and his younger brother Tom (born in 1962). While they returned for some of the time to their house on the Hartland peninsula in North Devon, the Trevors remained in Nigeria and there are numerous family photographs of the young boys playing in the gardens and countryside.

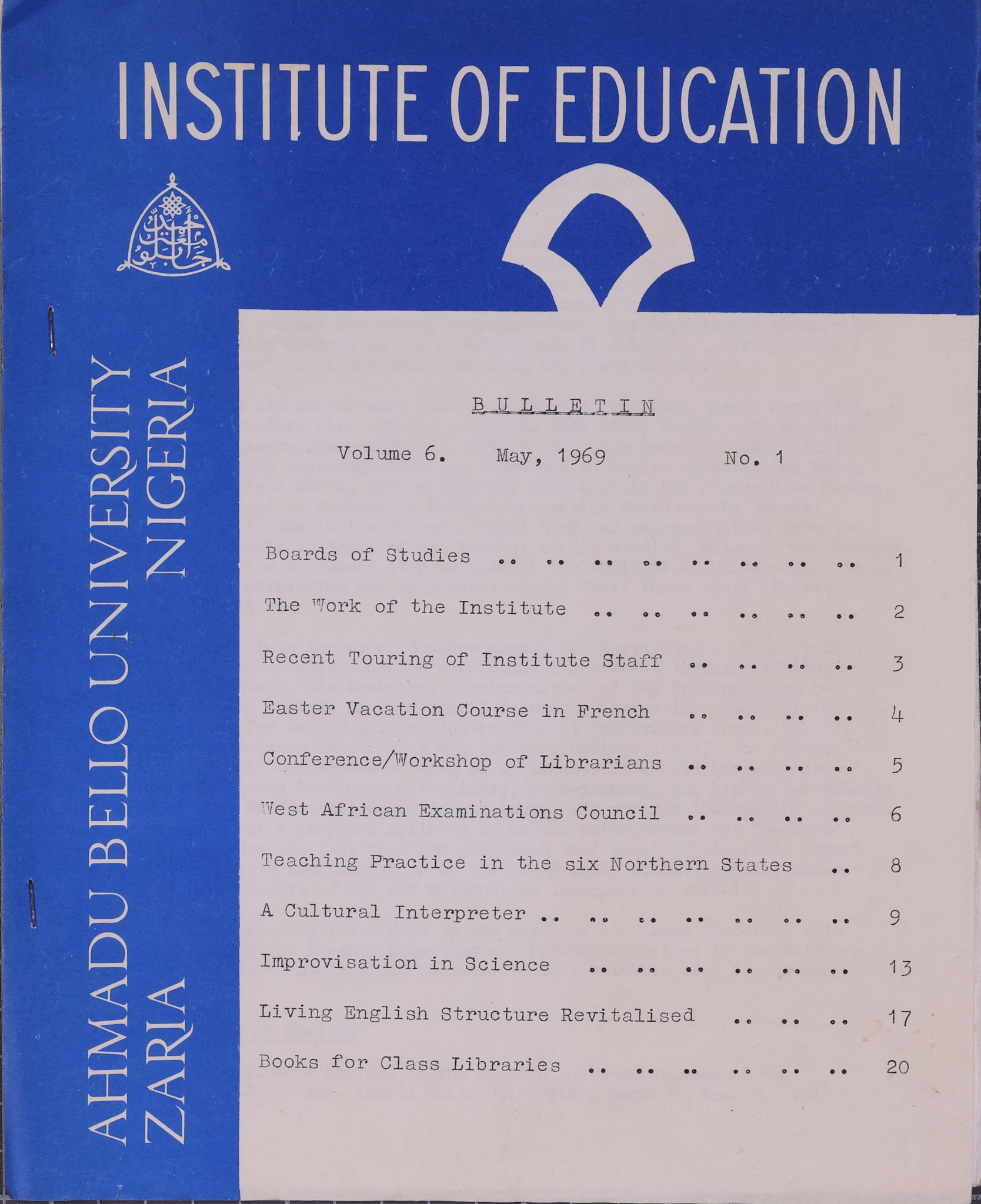

Tudor Trevor was involved in theatre and media production as part of his role as an agricultural development officer, and between 1958 and 1961 Jean worked with him in creating educational films and radio broadcasts in Hausa. Between 1964 and 1967 she taught African teachers at the University of Exeter and was appointed to the editorial team of the Commonwealth Teachers Magazine. A single issue is in the archive and provides some interesting impressions of England and Devon as recounted by teachers from countries such as Tanzania, British Guiana, Malawi and Jamaica.

The Development of Jean’s PhD

Jean’s experience of living and teaching in Nigeria for fourteen years, enriched by the conversations she had had in Hausa, had given her plenty of time to reflect upon the role of education in the lives of her pupils and their families. At some point her growing knowledge of the local community, combined with her evolving understanding of teaching practices and educational theory, combined to suggest to her the idea of researching these themes in a more formal study.

It is important to realise that her PhD was not undertaken as one single funded project, but was built around a series of short grants from different institutions, each of whom expected different things from her. Initially, her plan had been to write a fairly straightforward analysis of attitudes to female education, based on interviews with the schoolgirls, their families, local community figures and Islamic teachers, plus her own observations. After discussions with Gillmore Lee, Professor of Psychology at Leicester University, and Professor Robert LeVine of the University of Chicago, she was persuaded to follow their advice and switch to using formal quantitative methods to interpret her interview data. This involved devising questionnaires to which the questions could be assigned numerical values, that were then translated into code form, which could be recorded on punched cards.

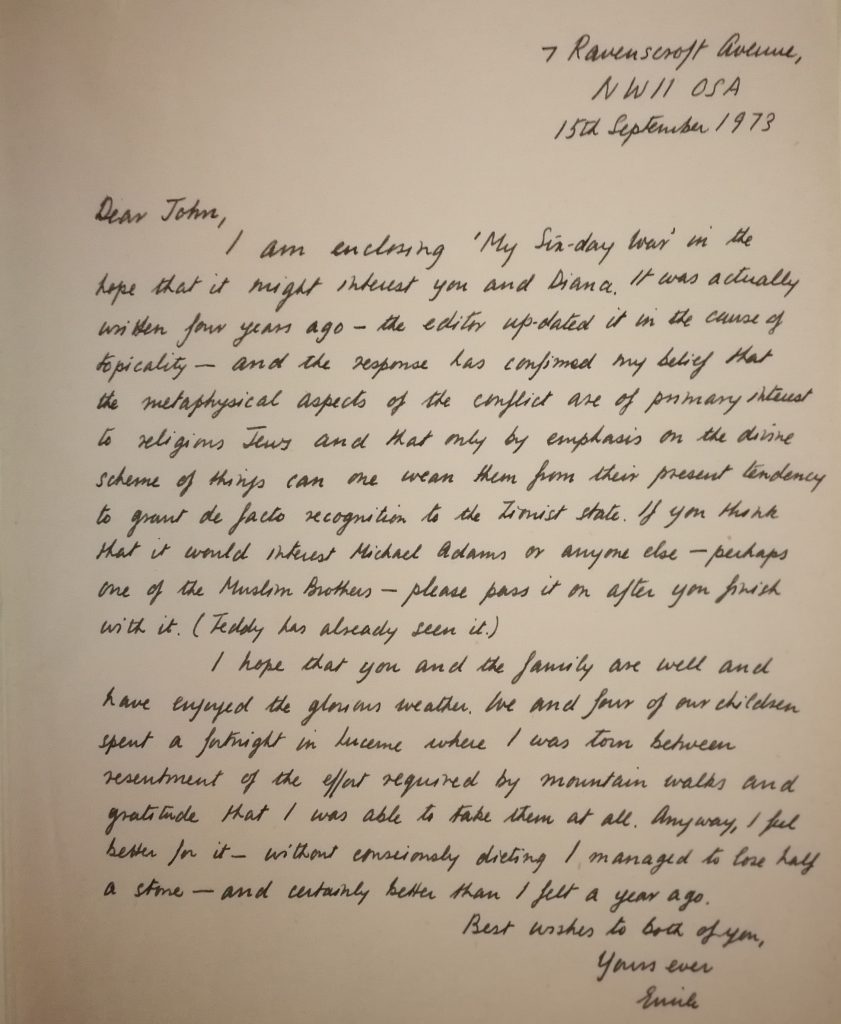

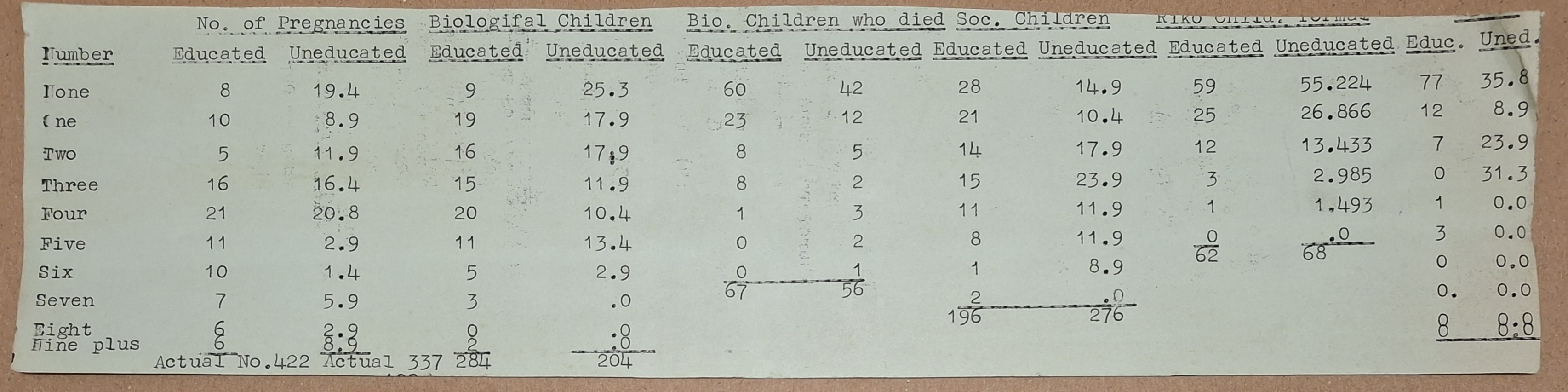

This work was carried out in challenging circumstances, with much of her grant money being spent on car repairs as she tried to drive around the countryside interviewing young Hausa women (see photo below!). Initially funded by a Commonwealth Postgraduate Research Scholarship, she then obtained – through the help of Professor LeVine – a Research Fellowship within the Child Development Centre at Ahmadu Bello University (ABU), Zaria in 1968. The University of Chicago money stopped at the end of December 1969 due to the US Department of Education cutting its grant (at the time of writing, this sounds very topical!) but further support from the Carnegie Foundation and the Ford Foundation allowed her to pursue her research under the auspices of the Department of Community Medicine at ABU. The Overseas Development Administration (ODA) offered Jean an Educational Development Award of £2,500 p.a. to cover the period between September 1971 and March 1972, but she then had to apply to the Population Council for another grant, for which she stated that her thesis title was ‘Effects of schooling in Moslem women’s attitudes to family size, child rearing practices and family planning in North West Nigeria’, emphasising its relevance for population studies. The University of Exeter then appointed her an Investigator in the Department of Education (Population Council Research Project) for six months from January 1973 to help her write up her thesis.

Academic Theories and Scholarly Circles

A name that appears regularly in Jean’s notes is that of Sir Frederick Lugard (1858-1945), a colonial administrator who was closely involved in the country’s affairs in the early 20th century. After working with the Royal Niger Company, he was appointed High Commissioner of the newly created Protectorate of Northern Nigeria in 1900, Governor of both the Southern and Northern Protectorates in 1912, and in 1914 became the first Governor-General of Nigeria, created through the unification of the two protectorates. While his policies included suppressing Fulani resistance to British rule – he organised the military campaign against the Emir of Kano, capturing Kano in 1903, as well as the Sultan of Sokoto Muhammadu Attahiru I, who was killed in battle in 1903 – Lugard was also intensely interested in education. He established a new Education Ordinance and Education Code for Nigeria in 1916 and his book The Dual Mandate in British Tropical Africa (1923) lays out in detail his theories about the place of education in colonial administration, stressing its value as a tool for development.

However, the close link between education and colonisation was deeply problematic in post-1960 independent Nigeria, given that Lugard regarded Africans as racially inferior to Europeans and his educational policy was explicitly utilitarian, aimed at producing loyal subjects who served their local community for the greater good, rather than seeing education as something of value to an individual in its own right. There was also an imbalance between the north and the south, both in terms of education and political strength, which contributed to the later divisions and secessions that arose during the second half of the century.

As Jean’s research focused on attitudes towards education and its purpose, she needed to engage with the ideas and legacy of Lugard, as well as those of contemporary sociologists, anthropologists and others. She collaborated a few times with the late Jerome H. Barkow (1944-2024), a professor at Dalhouse University in Nova Scotia who had spent many years studying the Hausa in Nigeria and Niger; Jean helped with a conference paper and there are several letters between them in the archive. Jerry wrote to her about another academic: ‘I find him quite old-fashioned theoretically, very much vulnerable to contemporary criticism of much African anthropology as frankly colonial’ and Jean’s papers reveal that she did not always see eye to eye with the views and conduct of senior figures working in her field.

The nature of her work meant she was in contact with a wide number of academics and professionals, in Nigeria, the UK and the USA, including anthropologist Sylvia Leith Ross (1884-1980) who settled in Nigeria in 1907 and founded girls’ schools in both Lagos and Kano, Dr Ishaya Sha’aibu Audu, Vice-Chancellor of Ahmadu Bello University and former physician to Bello himself, Professor Umaru Shehu of the ABU Institute of Health, Professor Richard D’Aeth of the University of Exeter’s School of Education, as well as prominent scholars such as Professor Mervyn Hiskett (1920-94) and anthropologist Professor Michael G. Smith (1921-93). There are also numerous letters from Hausa women, young girls, local teachers and the wives of important figures around Sokoto and Kano.

Islamic Aspects: from Jama’atu Nasril Islam to Boko Haram

Despite the uncertainties and trials of her PhD research, Jean often gave thought to finding employment once she had finished her PhD, and in 1973 she was invited by the Jama’atu Nasril Islam (Society for the Progress of Islam) to apply for the post of Principal of the Moslem Ladies College in Kaduna – an offer she declined, as she wanted to concentrate on completing her thesis. This was, however, recognition of the respect with which she and her work were regarded in the local Islamic community.

Jama’atu Nasril Islam (JNI) was established in Kaduna in 1962 by Sir Ahmadu Bello, Sardauna of Sokoto, as an umbrella organisation for the promotion of Islam, following advice from the Grand Khadi of Northern Nigeria, Alhaji Abubakar Gummi.

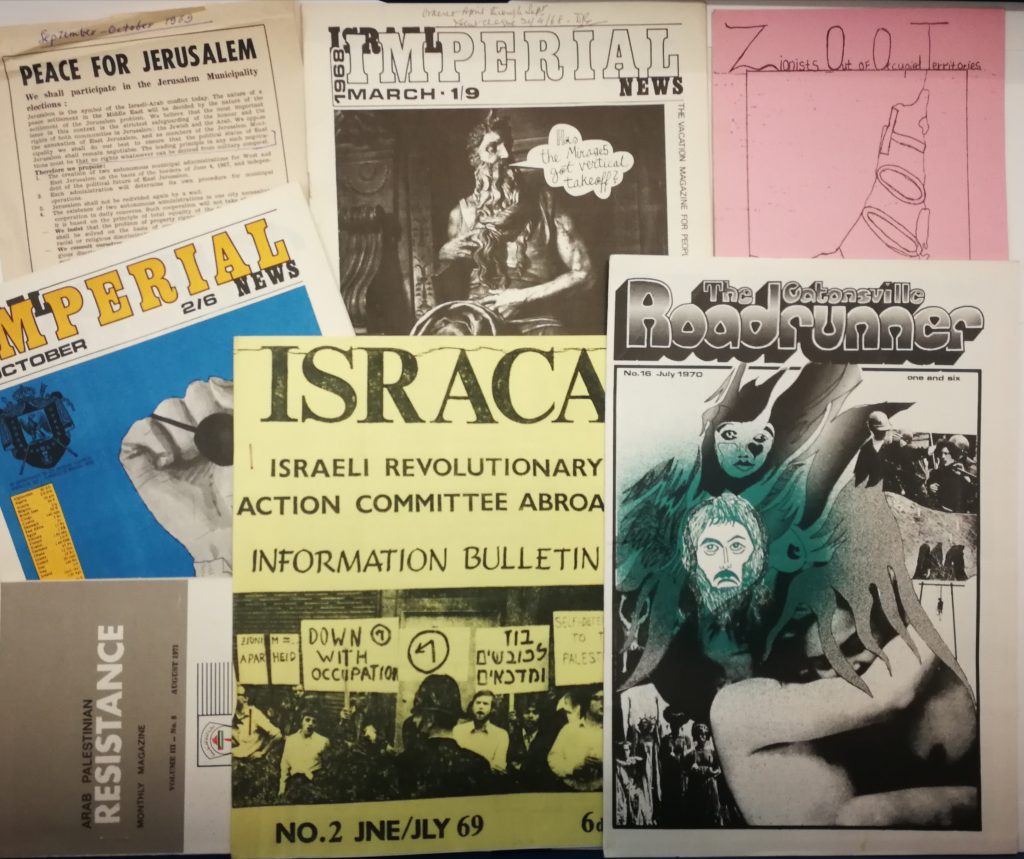

While Jean’s research focused on the social and cultural attitudes towards female education – such as whether girls who were expected to marry at a young age believed schooling would benefit them – this was intrinsically related to Islamic views on the value of knowledge, the role of women, and the differences between Quranic schools and western theories of education. Many of Jean’s notes related to Islam, including records of conversations she had with girls’ families, but she also undertook an interview with Alhaji Abubakar el Nafaty, Secretary of Jama’a Nasril Islam in December 1968, and another interview about education with the Grand Khadi, Alhaji Abubakar Gummi, the following May. Accounts of these interviews are in the archive, plus her description of a visit to the main Islamic school at Sokoto in February 1969, as well as a copy of monthly magazine Haske: The Light of Islam No.17 (1970) and various religious texts in both Hausa and Arabic.

Islamic attitudes towards western education in Nigeria have, of course, come under intense scrutiny in recent years since the rise of the militant group known as ‘Boko Haram’, which is often (mis-)translated as ‘Western education is forbidden.’ The group was founded in 2002 and its actual name in Arabic is Jamā’at Ahl as-Sunnah lid-Da’wah wa’l-Jihād, with the Hausa phrase ‘Boko Haram’ better translated as a prohibition of ‘westernization’ or ‘western civilization.’ The educational aspect is, however, a key element of the influence that the group so fiercely opposes, and their brutal campaign has seen the killing of tens of thousands of Nigerians, including many children, as well as the infamous kidnapping of almost 300 schoolgirls from a school in Chibok in NE Nigeria.

Much has been written about ‘Boko Haram’ in recent years, but the scale of violence and terror associated with the group’s campaign has not created a climate that supports much nuanced analysis. It is therefore interesting to find frank yet subtle discussions amongst Jean’s papers, such as her interview with the Emir of Gwanda in February 1969, in which he explained distinctions between attitudes to female education in Gwanda compared to Sokoto, and told her ‘Your boko can be as good at addini [religion] as a traditionally trained girl.’

She and Abubakar el Nafaty even discussed the theology of Teilhard du Chardin, exploring different understandings of the relationship between science and religion. In her conversation with the Grand Khadi, they talked in more detail about boko makaranta [western education] and his view that ‘Criticism of Boko is due to the false division of religion and secular life. This is a mistake – in Islam everything is a unity.’ In addition to these interviews, Jean recorded the views and stories of the wives of local professors and teachers, recalling their own experiences of education decades earlier, sometimes by European missionaries, and how the British colonial rule of Nigeria had changed how the people lived.

The papers, photographs, correspondence and other documents in the Jean Trevor archive provide insights into different aspects of Nigerian life at this period, including developments in both secondary and higher education, agricultural methods, Islamic movements, colonialism and the British relations with African countries at the end of the empire, as well as community health, textiles and costume, marriage customs and popular culture.

The Northern Region Marketing Board was the new name in 1954 for what had previously been the Nigerian Groundnut Marketing Board. We have material on the groundnut industry in Nigeria within the archive of the Imperial Institute (EUL MS 61):

The archive catalogue for EUL MS 79 can be browsed here.

To mark the 50th anniversary of the death of Jean Trevor this year, an event is being held at the University of Exeter on 2 July that will include a presentation from a visiting Nigerian scholar – more details will follow shortly.

Some writings by Jean Trevor:

‘A Cultural Interpreter’, Bulletin of the Institute of Education, Ahmadu Bello University Vol.6, No.1 (May 1969) pp.9-12

‘A preliminary report on the demographic aspects of a study of family change in traditional Moslem Fulani/Hausa urban centres – Sokoto’ [unpublished typescript]

‘Family change in Sokoto: a traditional Moslem Fulani/Hausa city’ in J.C. Caldwell et al (eds.), Population growth and socio economic change in West Africa (Columbia University Press, 1974)

‘Traditional Values and the Traditional Position of Women in Sokoto City’ [unpublished typescript]

‘The Education of Moslem Hausa Women of Sokoto, N.W. Nigeria’ [unpublished typescript]

‘Moslem women: what did our school do for them?’, (manuscript)

‘Moslem school girls: did our school help or hinder them?’ [unpublished typescript, January 1974]