To celebrate Exeter Poetry Festival and National Poetry Day I have been tweeting one of my favourite Ronald Duncan poems every day this week. Why not take a look at the @UOEHeritageColl twitter feed and read a few?

Ronald Duncan published five main collections of poetry during his lifetime (Postcards to Pulcinella [1941], The Mongrel [1950], The Solitudes [1960], Unpopular Poems [1969], For the Few [1977]). In addition to these he also published a five-part epic poem ‘Man’ (1970-74) and many other individual poems. On National Poetry Day I’m moving away from the polish of published works and taking a look at some of the unique manuscripts held within the collection which offer an insight into Duncan’s life and writing process.

The poet at work

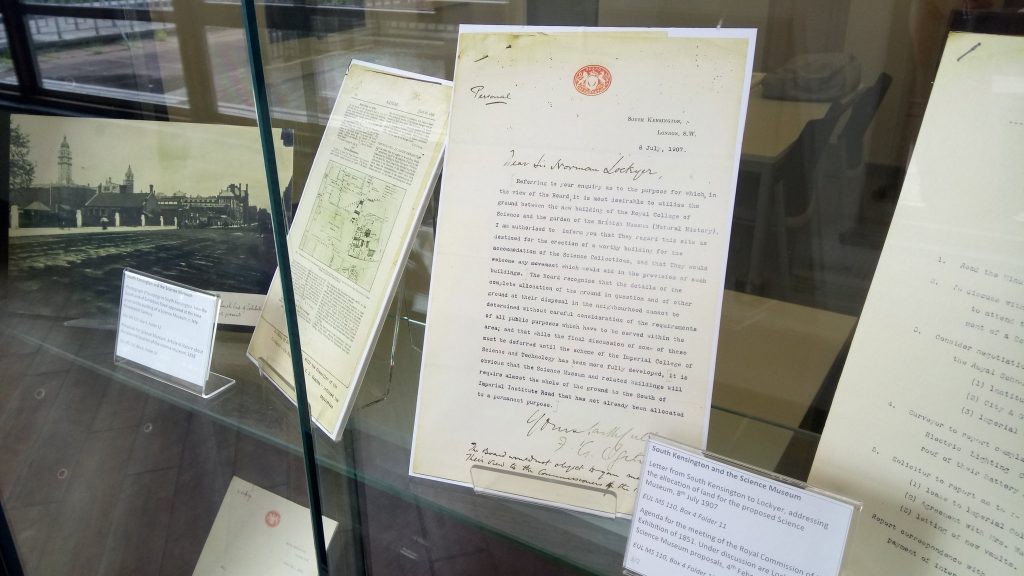

Portrayals in film and TV mean that I often imagine the writing process as a deeply organised one. The poet sits in front of his favourite typewriter, or pulls out a pocket notebook carried for such occasions, and reels off lines of beauty conveniently supplied by a voiceover. Working on the Ronald Duncan Collection has swiftly disabused me of this notion.

While the collection does contain many workbooks, and these seem to be an integral part of Duncan’s early working process, it also contains poems scribbled on paper plates, napkins, the backs of old letters and various assorted scraps of paper. To me this suggests a furious kind of franticness to the writing, an urgency that the poem must be recorded now while it is still fresh. One of the paper plates has clearly been used before being re-purposed and though it isn’t perhaps the romantic ideal of a typewriter, there’s a certain charm to the thought of Duncan wolfing down a finger sandwich or sausage roll before flipping the plate to compose a poem.

[slideshow_deploy id=’351′]

The gift of words

Like many other poets, a great number of Duncan’s poems are dedicated to family members and friends. Weddings, birthdays and christenings are all celebrated in verse and the grief of death is likewise immortalised. The idea of poetry as a gift is well established.

Duncan, however, takes this idea a step further than most. A manuscript poem dedicated to his granddaughter Karina reads ‘No Easter egg, my child, because I forgot to get one’ and provides a poem as a substitute. Though I’m not sure that I personally would have appreciated this exchange of chocolate for poetry as a child, it provides a lovely glimpse of family life. Another poem is dedicated ‘For Rose Marie, as good a craftsman in exchange for her parsley sauce’.

[slideshow_deploy id=’363′]

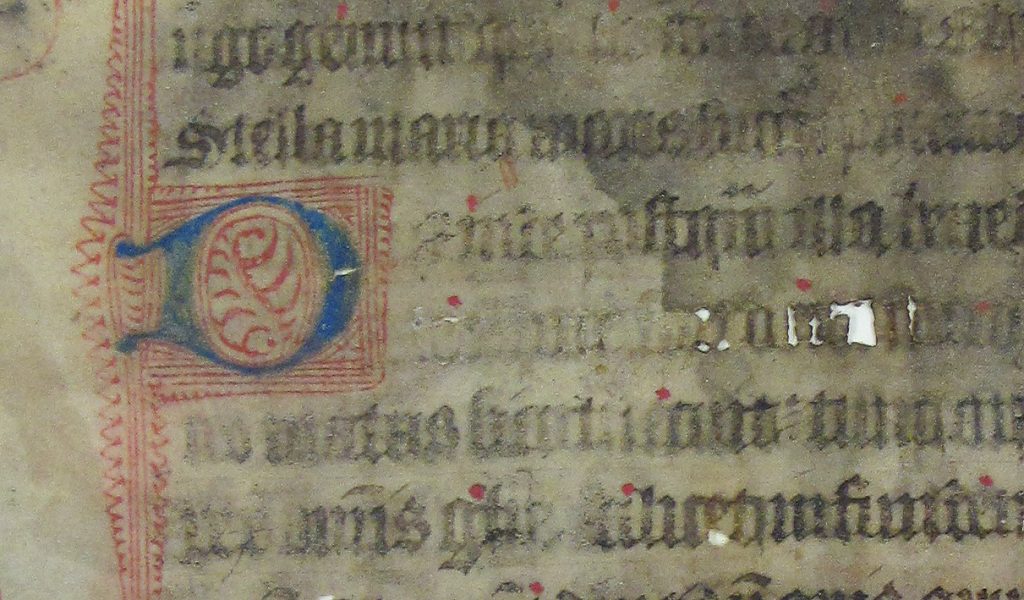

The art of poetry

Many of Duncan’s poems use colourful imagery to describe the natural world and a small proportion of the manuscripts in the collection have been illustrated to reflect this. The illustrations tend to be painted onto the manuscript and vary from simple bright swirls of colour to abstract representations of the poems’ subjects. The vibrant designs give a tantalising glimpse of what was in Duncan’s mind when composing the poems.

[slideshow_deploy id=’370′]

The final word

However familiar I become with the Ronald Duncan Collection, I am always aware that my interpretation of Duncan’s work is only one possibility. With this in mind I leave you with an audio clip of Ronald Duncan talking about poetry, one line of which I particularly enjoy;

“If you can’t hear me it is probably because I don’t speak loud enough, and if you don’t understand me it is because the poetry isn’t any good”

(please note that in some browsers the ‘Play’ button does not seem to appear. If you click before the timer on the left hand side of the sound bar it should start playing)