While taking a slight repast in the Temple of Venus, we were surrounded by a bevy of young girls dancing the Tarantella

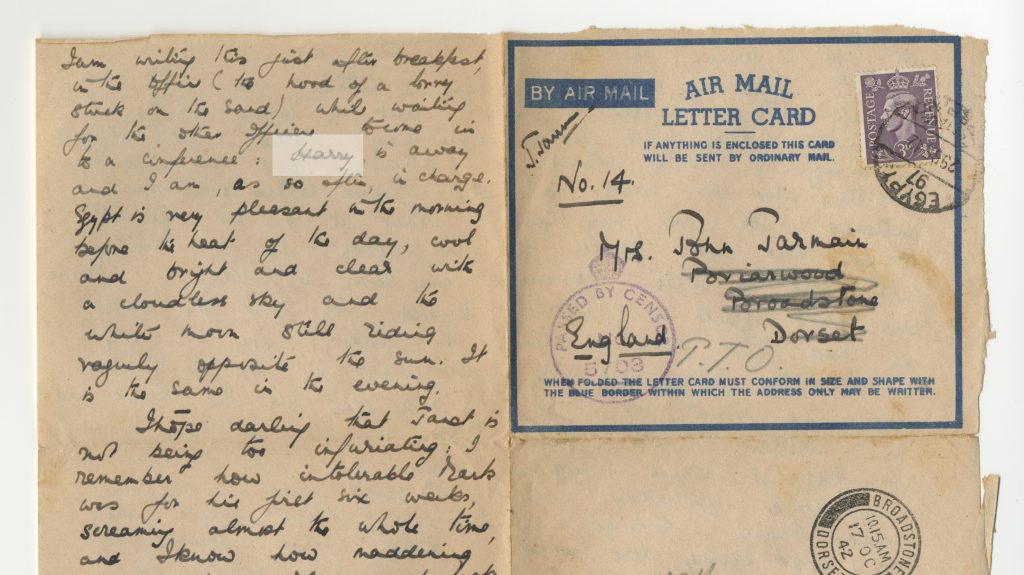

– George H.P. White R.N., Diary entry, May 1836. EUL MS 418/6

Old travel narratives can be a source of reading pleasure as well as edification, as the charm of their quaint language and their unusual perspectives on regions both familiar and unfamiliar can help us to think again about our own views of the world. The literary pretensions and insatiable curiosity of many of these travellers combined to produce chronicles of their journeys that sometimes reveal as much about the culture from which they came as they do about the culture they were exploring.

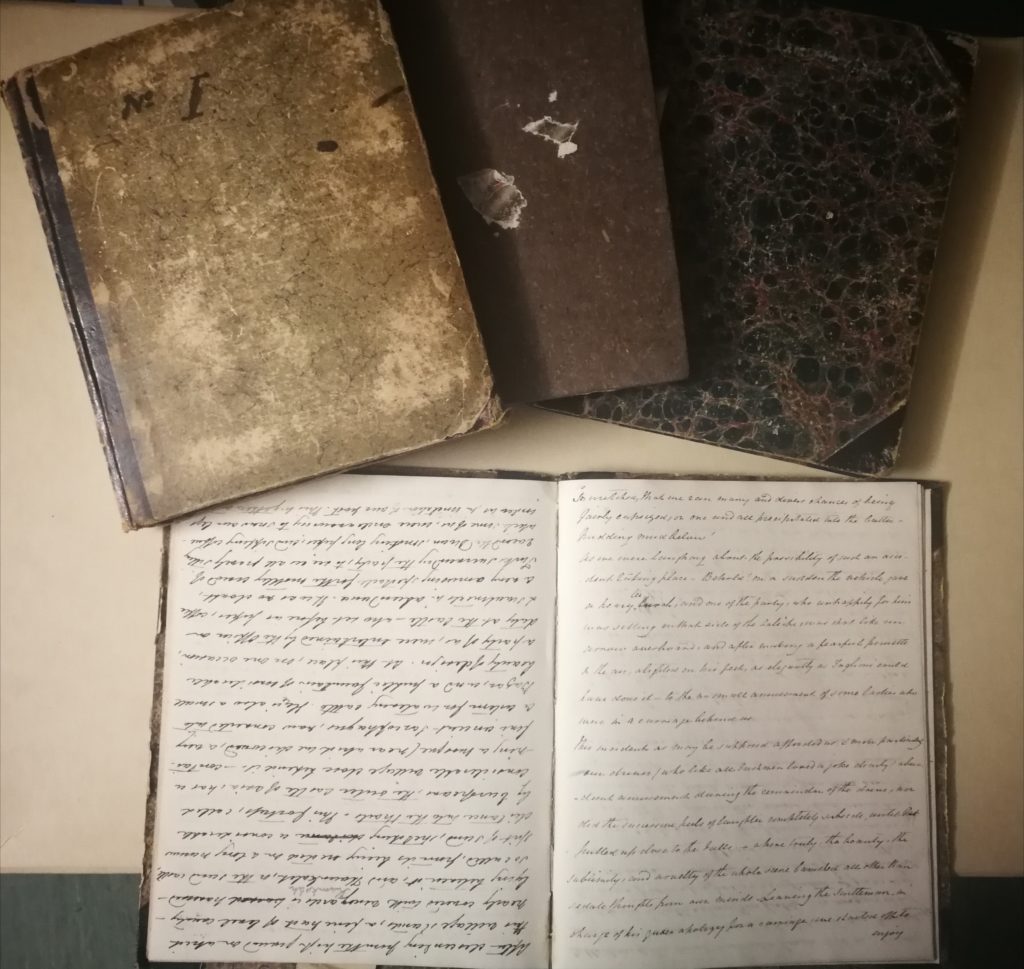

We are fortunate to have in our collections a series of six notebooks written by Admiral George Henry Parlby White R.N. (1802-82) between 1819 and 1845 when he was a young naval officer stationed in the Mediterranean. These record his journeys around the coasts of Spain, Italy, Greece, Malta, Turkey, Morocco and Tunisia, as well as voyages further afield to South America and Canada. He later served on HMS Implacable during the blockade of Alexandria in 1840 when the British navy engaged with Egyptian forces who had invaded Syria, although these events are not included in these books.

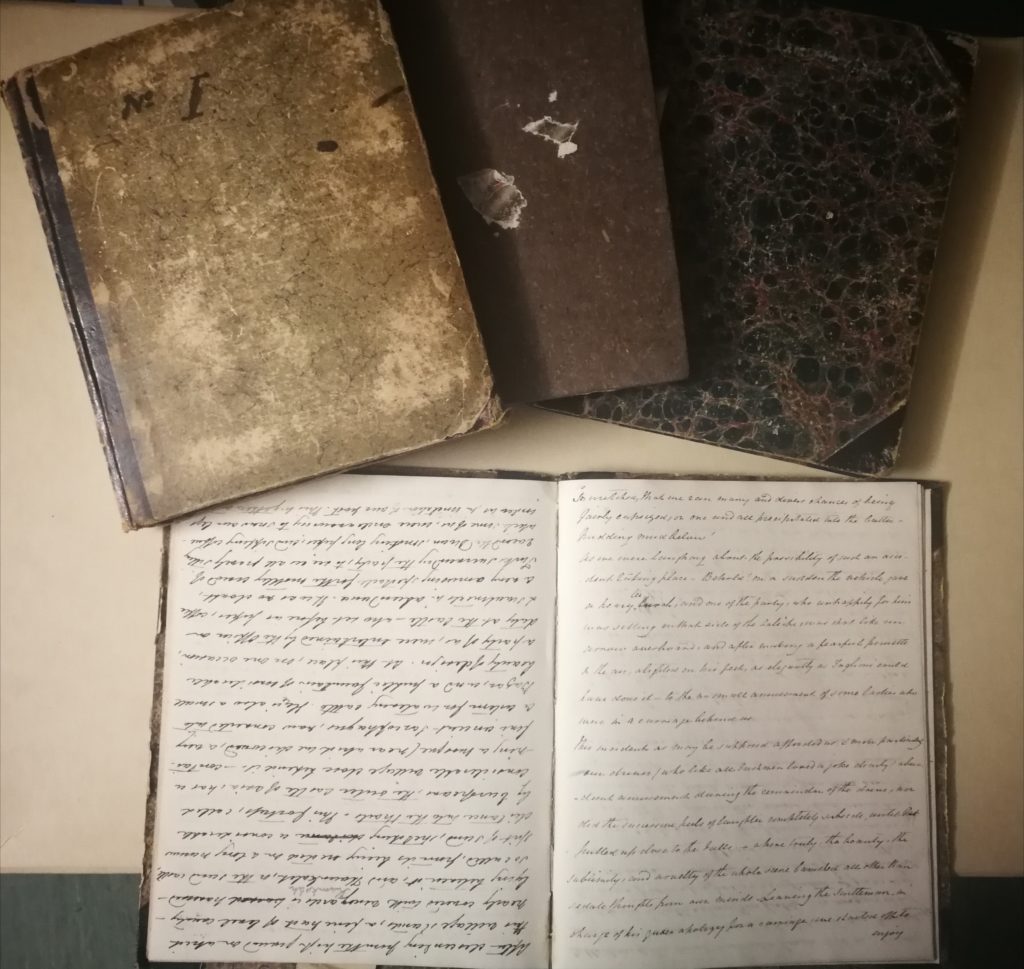

Four of the six notebooks in which the diaries are written EUL MS 418

The author of the diaries had been born into a naval family. His father Admiral Thomas White (1766-1846) was a native of Buckfastleigh and lived at the Abbey House, the castellated Gothic mansion built on the ruins of medieval Buckfast Abbey. Thomas spent 66 years in the navy, having entered the service in 1780 at the tender age of eleven. Three of his four sons followed him into the Royal Navy, with George being joined by his younger brothers Edward John White (1805-47) and Richard Dunnington White (1814-99), whose son Vice-Admiral Richard White died in Exeter in 1924. Richard also took part in the naval operations off the Syrian coast and painted a watercolour The Bombardment of St. Jean D’Acre – November 3rd – 1840 which is now held in the collections of the V&A.

George was born on 11 October 1802 at Droxford in Hampshire, and after entering the Royal Naval College in November 1816, he served on ships within British waters before joining the crew of his father’s ship HMS Superb in August 1819. The diaries begin with an entry for 9 September 1819: ‘Sailed for South America in HMS Superb. Longeur and Hyperion in company.’

HMS Superb (on the right) engaging with the French flagship Impérial at the Battle of San Domingo in 1806. Painting by Nicholas Pocock, National Maritime Museum

All the diaries are written longhand in lined notepads, with sporadic inclusion of dates and long prose passages that continue over several pages. It is not long before the reader gains some sense of White’s character and interests. Having caught sight of Tenerife and crossed the Equator, a dolphin is killed for food and the young midshipman writes out some thirty lines on ‘The Dying Dolphin’ by William Falconer – an extract from Canto II of the poem The Shipwreck (1762.) The wording varies in several places from the published text, suggesting that White was quoting the passage from memory. As the diaries proceed, the sailor’s literary interests and skills become increasingly apparent, as does his intellectual curiosity and observant eye.

When the ship arrives in Rio de Janeiro (24 October 1819) he writes a vivid description of the sunset over the harbour, and is soon exploring inland, recording in detail the riding skills, habits and cuisine of the gauchos, or cowboys, of Maldonado (January 1820.) Life here was not without danger – White’s diary notes how ‘The Hon. Lieutenant Finch was basely assassinated when returning from a shooting party,’ (29 August 1820) – but he evidently found much to interest him in the region, from the ‘immense number of sperm whales’ on the voyage to Valparaiso (13 February 1821), to flamingos, condors and other local birdlife (15 September 1821) – indeed he regarded Chile as truly ‘the country for the Poet, the Artist, the Botanist, in fact every lover of nature and her works; at every step he sees something new, he treads on something yet unknown.’ (13 April 1821.) When not exploring South America’s flora and fauna, there was naval work to be done, such as a fortnight’s pursuit of the Chilean pirate Vicente Benavides (5-19 July 1821); although White and his crew failed to find Benavides, he was captured soon after and executed the following February.

The first diary ends in January 1825, by which time White had attained the rank of lieutenant. Later that year, he would be promoted to captain. At the back of the notebook, written in the opposite direction, are almost 100 pages of poems and prose passages, some of which – such as Lines on Botogago Bay, Rio de Janeiro and Admiralty Leave to Tell! A Soliloquy. In the Royal Marine Barrack Yard – appear to be White’s own work. Others have been selected and copied out from books, periodicals and other sources in the manner of a commonplace book, including poems in Greek and Italian, the work of Gabriel Rossetti and Petrarch, an Ode to Lord Byron and some lines from Morning Twilight, by ‘Maria Colling, a servant girl living at Tavistock’. Some of these passages are dated as late as 1845, indicating that the notebooks were reused.

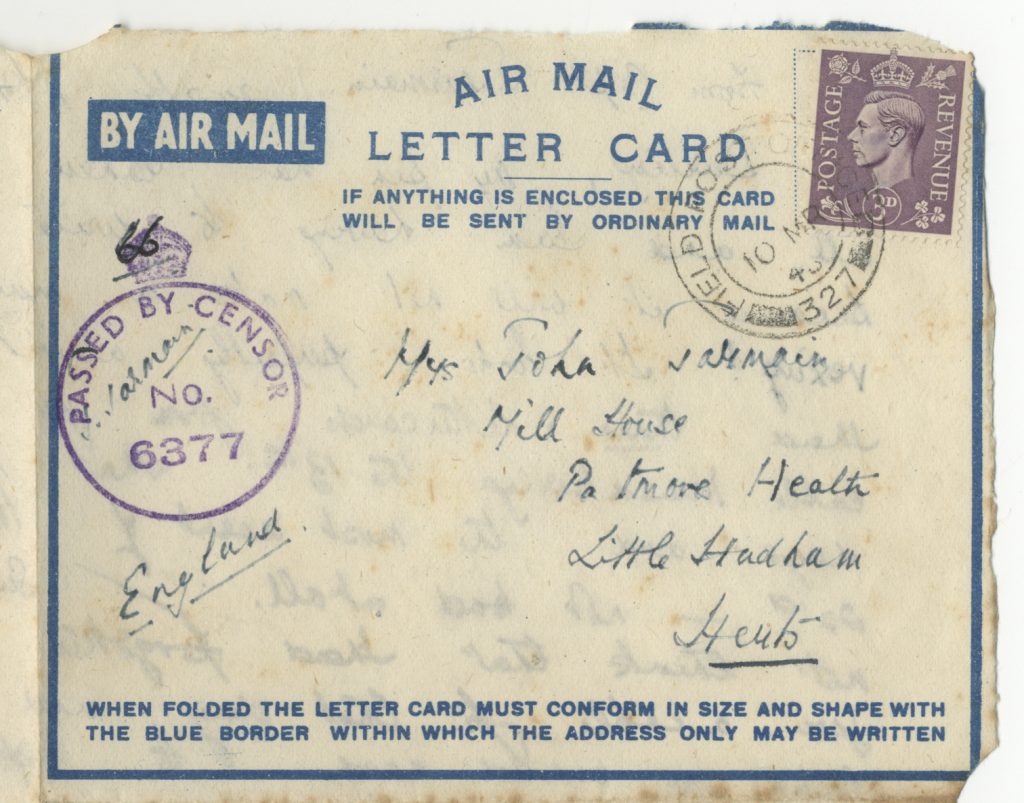

There is more evidence of reuse in the later volumes, with some entries duplicated in different books, indicating that the diaries were copied out at some point. The wording of the two versions is not always identical. Although we only possess six notebooks, these are numbered in pencil as Nos. 1, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7, and the full extent of the original diaries is unclear. Pencilled dates have been written inside the covers, either by White or a later hand, but these do not always represent the contents accurately. An approximate summary of the actual dates would be thus:

Notebook I September 1819 – January 1825, with additional material up to 1845

Notebook II September 1829 – June 1830

Notebook III August 1830 – September 1834

Notebook IV February – August 1834, and September 1841

Notebook V August 1836 – May 1840

Notebook VI May 1836 to May 1838

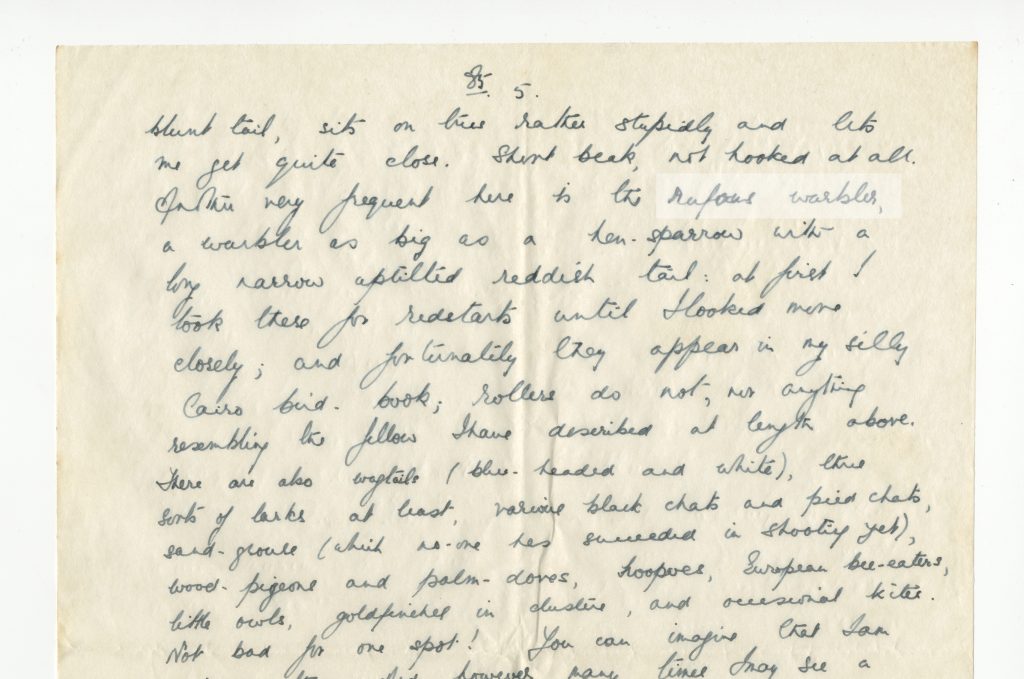

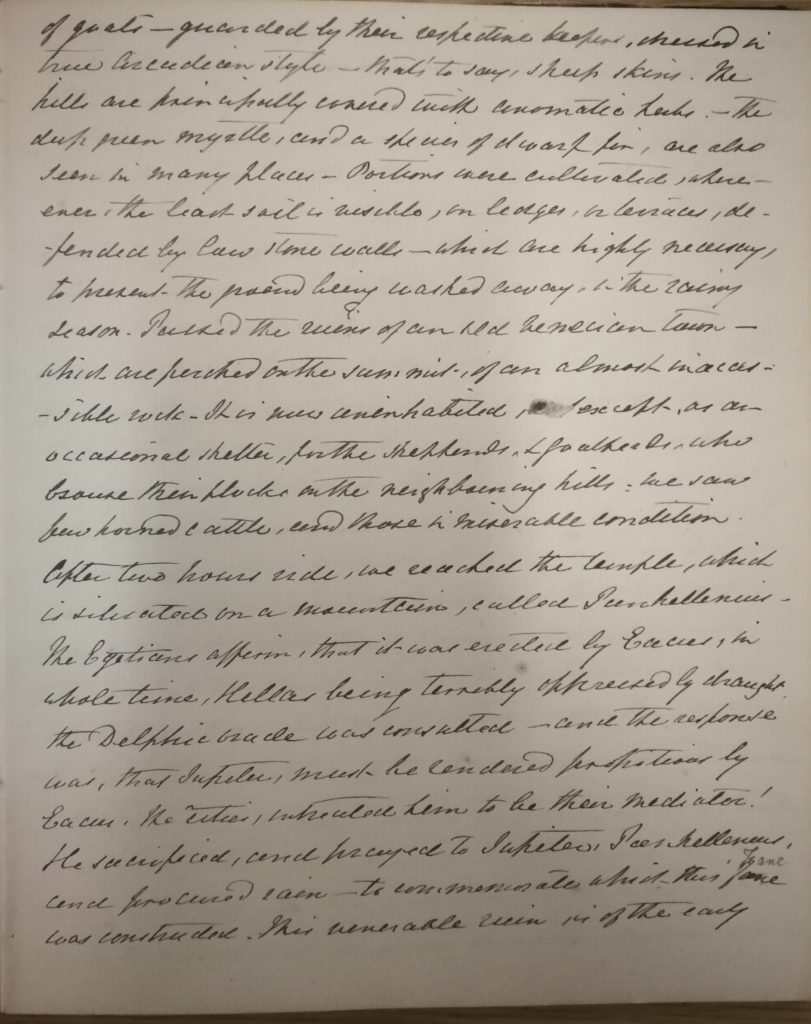

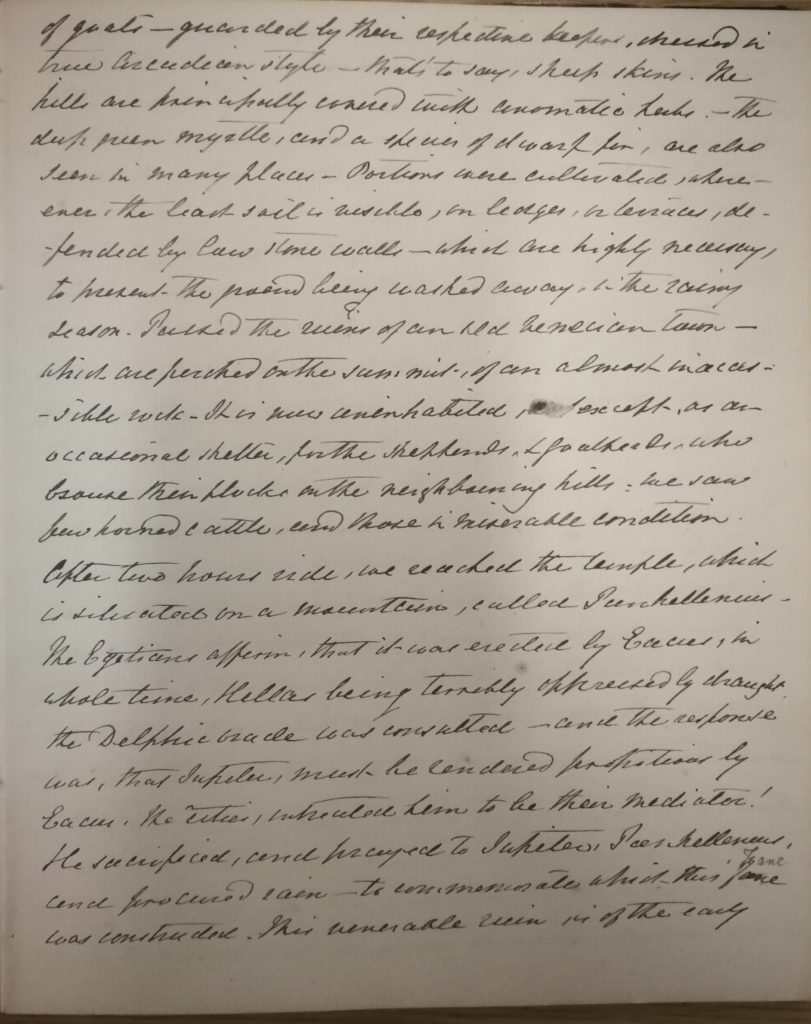

Part of White’s account of his visit to the temple on Aegina, December 1829. EUL MS 418/2

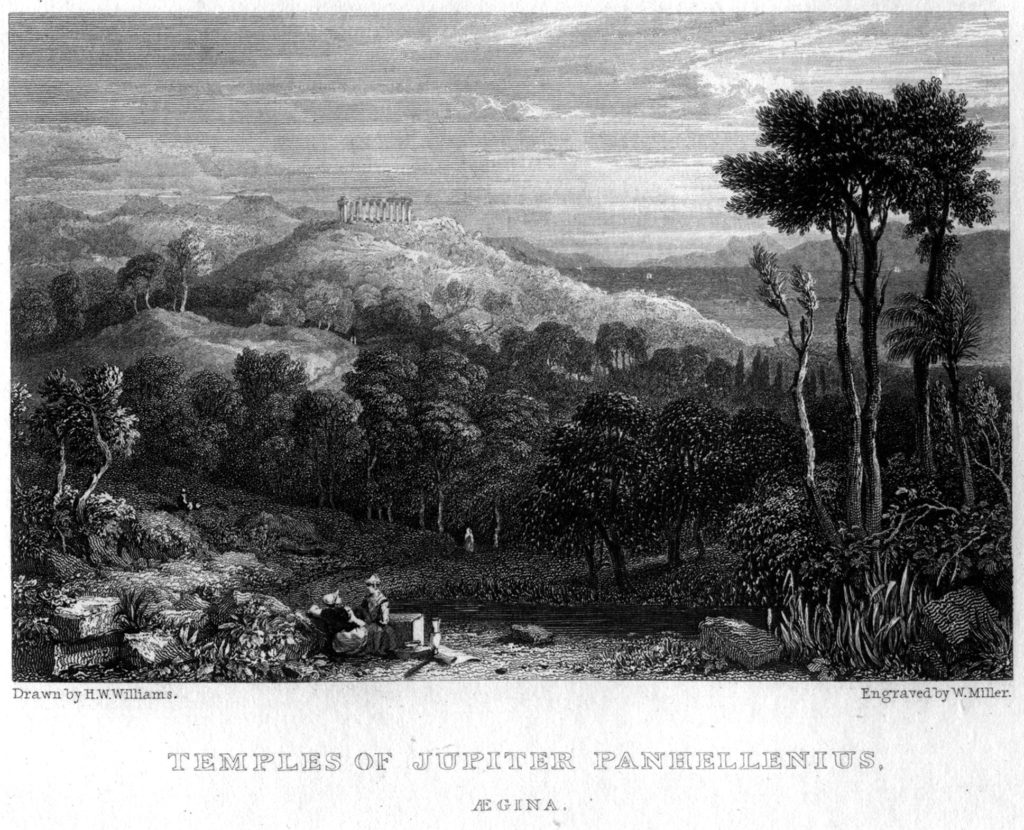

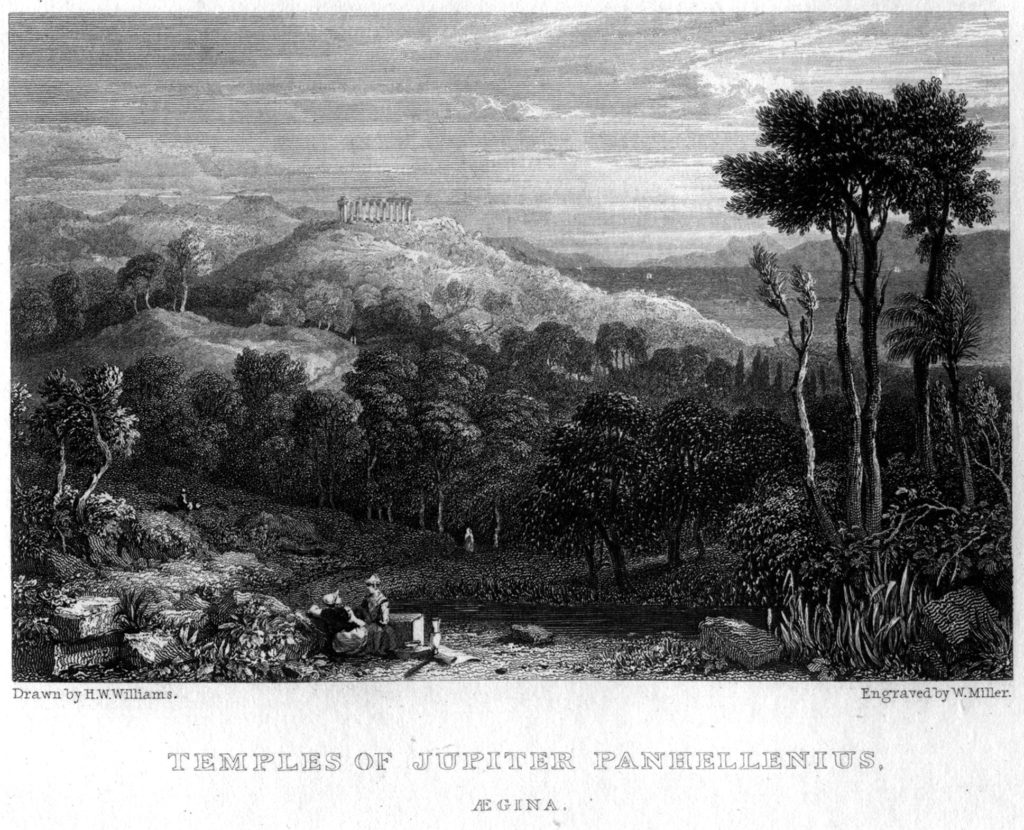

Following White’s departure from South America he had a brief stint off the coast of Africa, but most of his subsequent career was spent in the Mediterranean, which is the background to the events recorded in the rest of the diaries. Notebook II chronicles his ship’s constant cruising between Gibraltar, Malta and the coasts of Spain, Italy, Greece and Turkey. Those who imagine that sailors spent their time ashore seeking the pleasures of wine, women and song might be pleasantly surprised to find White and his fellow officers pursuing other interests. Upon reaching the Greek island of Aegina, he writes ‘Let out with ten officers of our ship to visit the remains of the Temple of Jupiter.’ (4 December 1829). This was the famous Temple of Jupiter Panhellenius, which had only recently become known in the west. After an energetic walk across the island, White provides a detailed description of the site as well as recounting the legends about its foundation. It has since been recognised as being dedicated to Aphaius rather than Jupiter.

‘Temples of Jupiter Panhellenius, Aegina’ engraving by William Miller published in H.W. Williams, Select Views In Greece With Classical Illustrations (London, 1829)

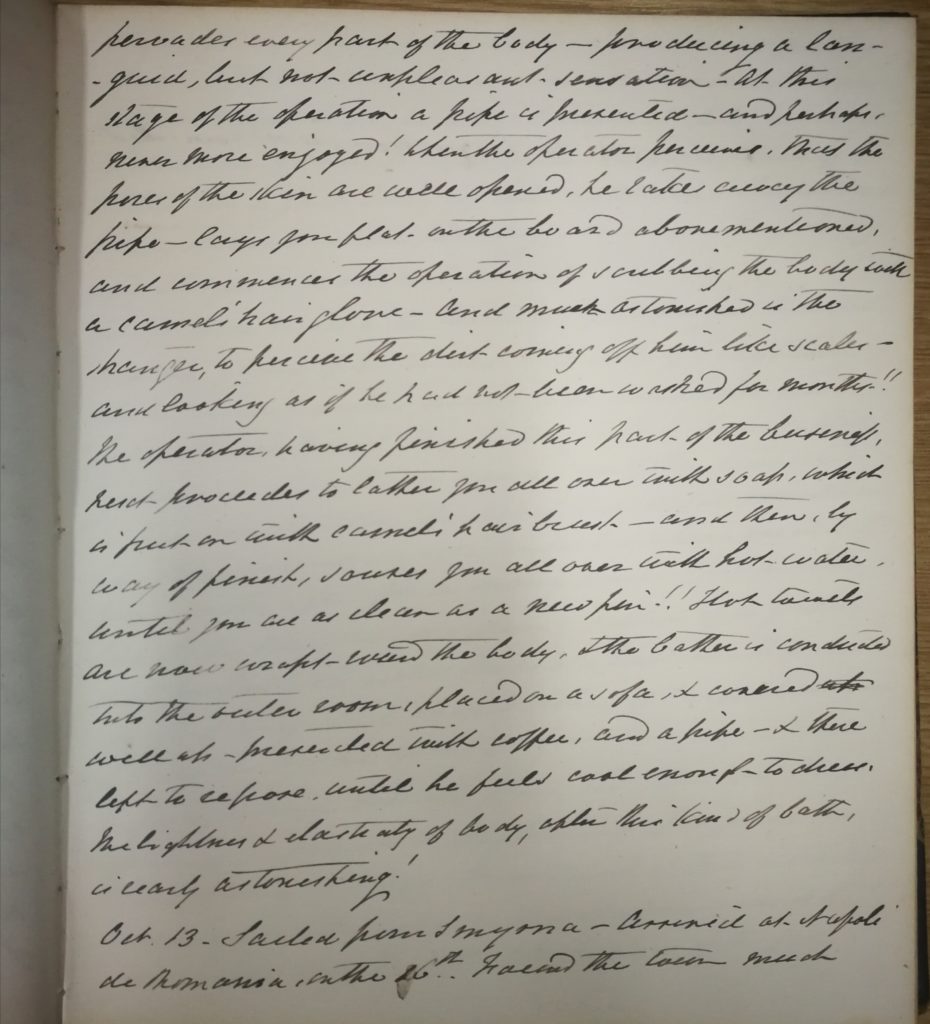

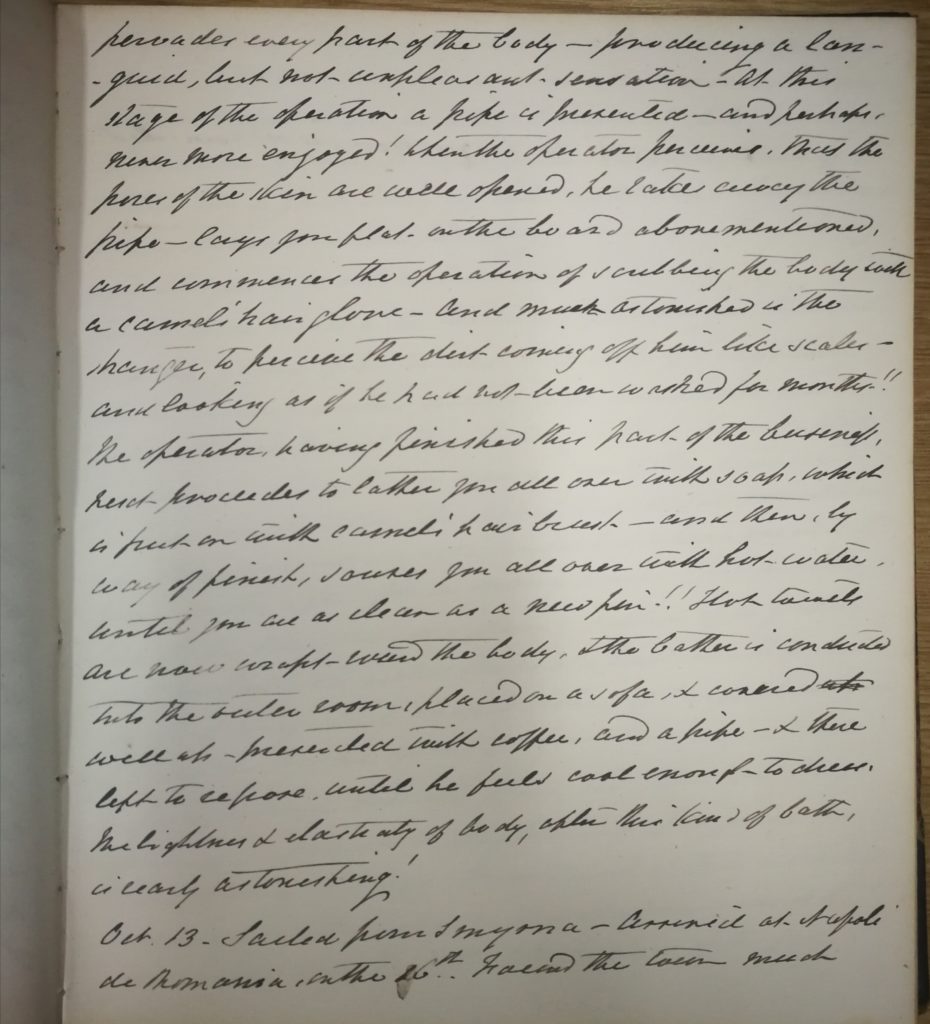

He sailed on to Smyrna in modern-day Turkey, where he visited a mosque and commented, ‘There is something particularly impressive in the simple and unostentatious worship of the Mahomedan. No noise, no bustle, no laughing and talking, as is often the case in Christian churches.’ (20 December 1829). On a later visit to Smyrna he enjoyed a Turkish bath, which he also describes in detail (Notebook III, 17 September 1830, see below.) His ship then moored at Parikia on the Greek island of Paros, where he led his fellow officers into the nearby marble quarries ‘in search of antiquities’ (9 January 1830) only to stumble across the famous bas-relief depicting the Festival of Silenus (a companion of Bacchus). A few days later Captain White ‘formed a large party from our ship to explore the celebrated Grotto of Antiparos’ (15 January 1830.) The party’s enthusiasm for seeking out ancient ruins gives some insight into the degree to which their view of the region was highly coloured by knowledge of classical literature and mythology.

White’s account of a Turkish bath in Smyrna, September 1830. EUL MS 418/3

Later entries cover his visits to Siciliy with detailed descriptions of the Cathedral at Grigento, antiquities in the museum at Syracuse and the Benedictine monastery at Catania, pursuing a Spanish privateer off the coast of Gibraltar, sailing to Tangiers and Tétouan on the African coast, a narrow escape during a boar hunt in Tunisia, a description of the Carlist wars in southern Spain, including the brutal murders of the governors of Malaga and the military exploits of General Miguel Gómez Damas and Don Antonio Escalante, plus carrying troops of the 71st and 73rd regiments around Quebec and Halifax. There are interesting passages in which White ponders on the location of Troy, expressing his doubts about the theories of Dr Edward Daniel Clarke (1769-1822) and advancing his own ideas as he examines inscriptions and the terrain around Berika Bay and Bounarbashi (Pınarbaşı in modern Turkey.)

White married in 1847, retired in 1863, and was subsequently promoted to Rear Admiral (1865), Vice Admiral (1871) and Admiral (1877). Returning to Devon, he lived in Ashburton for a while and later at Rockwood Villa off Totnes Road in Newton Abbot, where he died on 29 December 1881 leaving two daughters and a son.

The diaries would be of interest to anyone doing naval or maritime studies, particularly with regard to the Royal Navy, as well as those researching Victorian travel, antiquarianism, amateur archaeology and classical studies, the political and military histories of Spain and Latin America, the Kingdom of Greece, the Ottoman and British empires, early Victorian encounters with Islam and the Orient, the relationship between Britain and its colonies, 19th century memoir-writing and vernacular literature. The local connections are also strong, with the links to Devon and occasional references to the west country. More details about the contents of the diaries can be found in the online catalogue entries here.