Those familiar with the Muslim Brotherhood will likely associate the organisation with Egypt, the place of its origin and the centre of its activities for much of its 90-years of existence. Founded by Hasan al-Banna in Ismailia in NE Egypt in 1928 – in part as a response to the dissolution of the Islamic Caliphate in 1924 after the collapse of the Ottoman Empire – the Muslim Brotherhood was one of many small Islamic groups dissatisfied with the secular character of Egyptian society and the continuing occupation by British forces under the liberal monarchy of King Fuad I. By the late 1930s, however, it had over half a million members in Egypt alone and over the following decades would gradually become a powerful force of influence across the Arab world – despite a series of government prohibitions and crackdowns that saw thousands of its members imprisoned or executed.

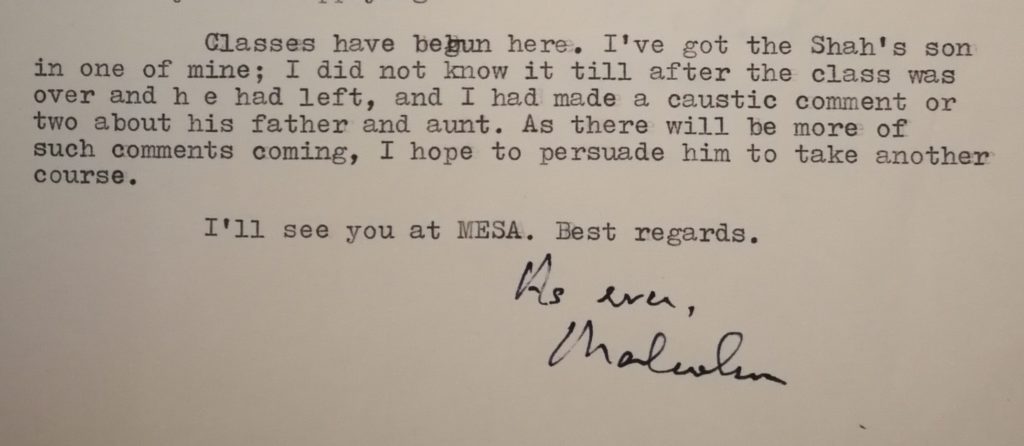

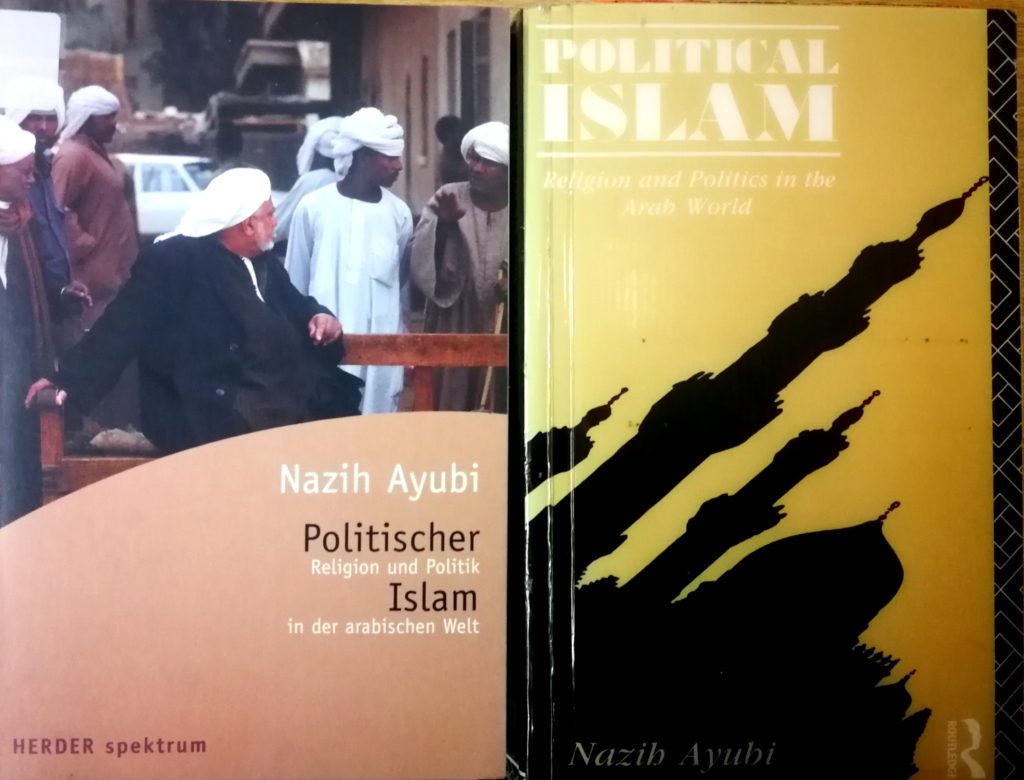

A transnational movement rather than a political party, the Muslim Brotherhood was never in a position of power until the 2011 uprising that followed the ‘Arab Spring’. The thirty-year Presidency of Hosni Mubarak has been analysed in detail by Nazih Ayubi and many papers in the Ayubi archive offer insights into Egyptian life, society and economy during this period, but human rights abuses and corruption under Mubarak were the focus of the political demonstrations that took place in Cairo’s Tahrir Square during the spring of 2011, leading to Mubarak’s resignation and the first ever democratic election in Egypt’s history. The new president, Mohammed Morsi, was a member of the Muslim Brotherhood. A year later, he was deposed in a coup led by General Sisi – who became the new president – and Morsi was imprisoned in jail in Cairo, where he died in June 2019.

The role played by the Muslim Brotherhood in Morsi’s rise and fall is a topic that will continue to be debated for many years, and it will be interesting to see what insights Victor Willi forthcoming book The Fourth Ordeal: A History of the Society of the Muslim Brothers in Egypt, 1968-2018 (Cambridge University Press) has to offer. The Muslim Brotherhood’s activities outside of Egypt have perhaps received less scrutiny, which is what makes Abd al-Fattah M. El-Awaisi’s study, The Muslim Brothers and the Palestine Question 1928-1947 (London: Tauris, 1998) so fascinating.

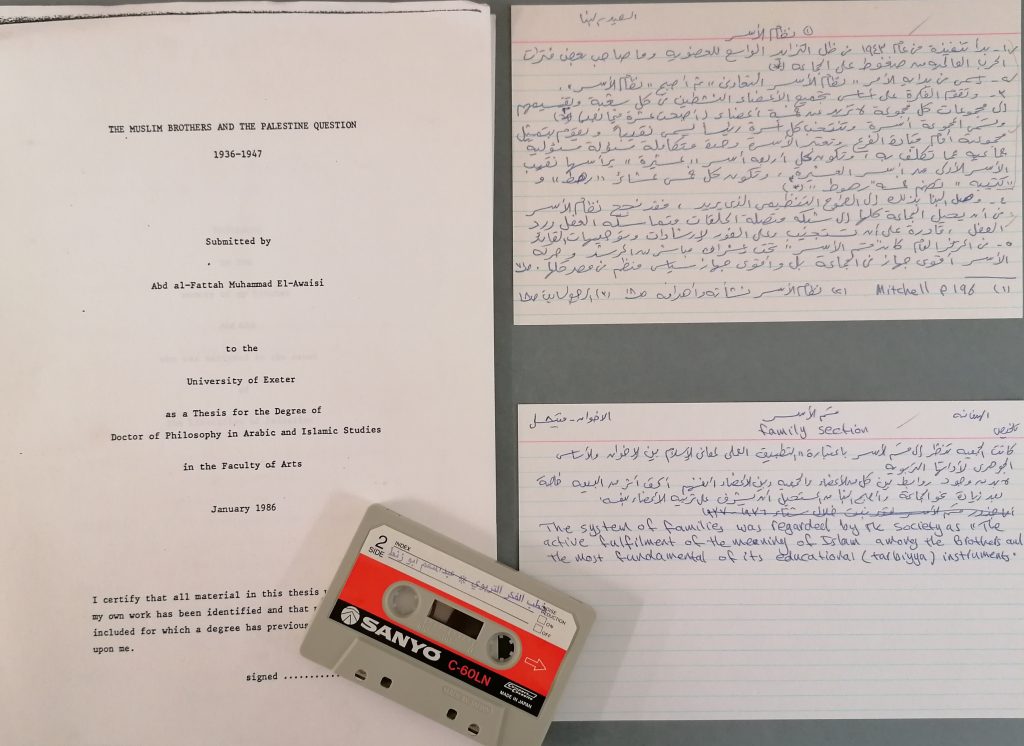

Some items from the El-Awaisi archive

El-Awaisi was born in Palestine, in the Gaza Strip, and after studying at Kuwait University came to Exeter to pursue a Ph.D under the supervision of Michael Adams. His thesis, entitled The Muslim Brothers and the Palestine Question, 1936-1947, was successfully submitted in January 1986, after which he took up an academic post at the University of Hebron in the Israeli-occupied territory of Palestine. He was head of the history department when he was deported by the Israelis in 1992, a traumatic experience that caused him a great deal of suffering and ill-health in addition to separating him from his family. Professor El-Awaisi was later reunited with his wife and children, and held academic posts in Malaysia and Turkey. In 2001 he became the first Principal of the Al-Maktoum Institute in Dundee, where he co-wrote Time for Change: Report on the Future of the Study of Islam and Muslims in Universities and Colleges in Multicultural Britain (2006) with Professor Malory Nye, who succeded him as Principal in 2008. In recent years he was been committed to a new interdisciplinary field designated ‘Islamicjerusalem [sic] Studies’, which aims at exploring an Islamic understanding of the Holy Land through theology, history, geography, architecture and archaeology.

El-Awaisi’s recent work is, arguably, rooted in the research undertaken forty years earlier for his PhD thesis, which examined in detail the Muslim Brotherhood’s belief that Palestine occupied a position of unique significance within Islam, and the ways in which their engagement with this issue played out through three successive phases: that of propaganda, military preparations and armed conflict.

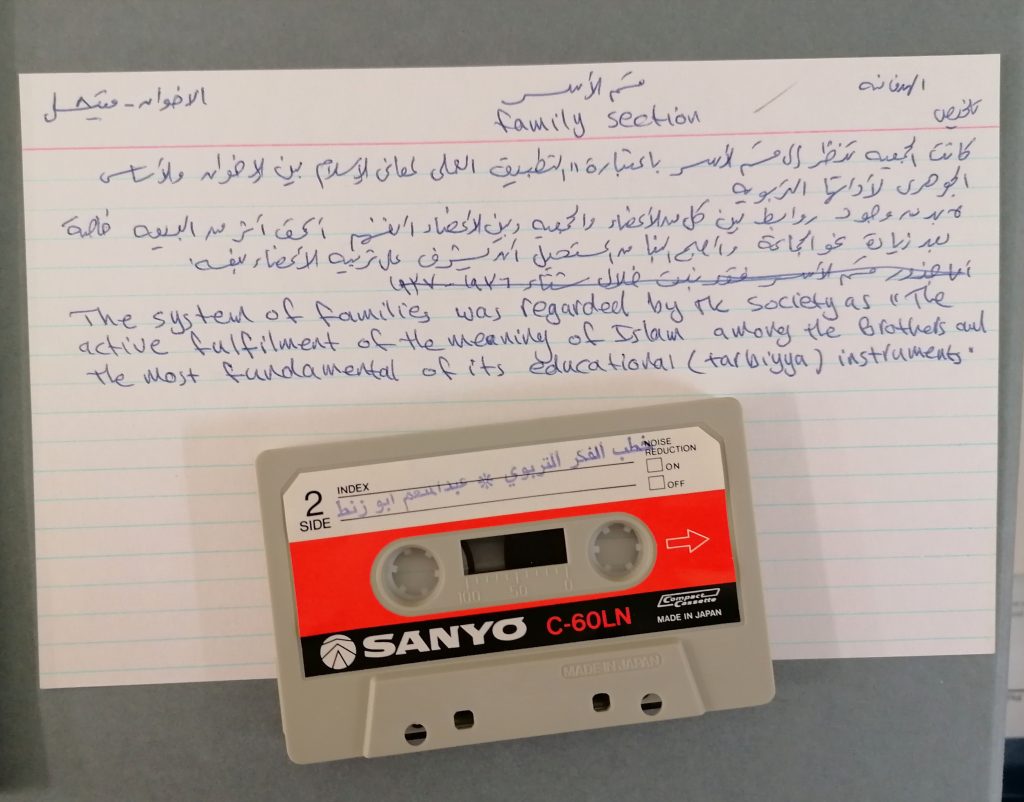

Tapes of Abu Zant with one of El-Awaisi’s index cards

Under Hasan al-Banna, the Brothers began with the fundamental concept of Islamic umma [أمة] which emphasises that all Muslims belong to a ‘spiritual nation’ which transcends geographic boundaries and racial distinction. At first, they adopted a principled and respectful stance towards non-Muslims, both Christians and Jews, as People of the Book, but this changed in response to the Zionist movement and its demands upon Palestine. Believing that Palestine occupied a special place within the Islamic umma and that all Muslims had a sacred duty to defend the Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem, the Muslim Brotherhood took an increasingly hostile stance towards Judaism, including the distribution of ugly anti-Semitic material. The Brothers’ commitment to fighting in Palestine was based on a fusion of the concepts of umma and jihad [جهاد ], so that the defence of Palestine was seen both as a nationalist and a religious cause. At this time however, British policy was aimed at keeping Egypt isolated from the Arab world, with the consequence that Egyptian politicians were much more concerned with domestic issues and showed little interest in Palestine. Even as late as 1931, there was little support in Egypt for Pan-Muslim movements, which is why the Muslim Brotherhood had to devote so much energy to propaganda in its early years.

As El-Awaisi’s thesis reveals, one of Hasan al-Banna’s first actions (in 1927) was to send a message of support to the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, Haj Amin al-Husayni – who was, incidentally, a good friend of Ernest Richmond. The Brotherhood’s first activity outside Egypt was in Palestine in 1935, when a delegation of Brothers travelled to Jerusalem to visit al-Husayni before meeting others sympathetic to their aims in Damascus. After returning, their offices in Cairo became a centre for the Palestinian resistance movement, and over the next decade they would take an increasingly active role in military operations within Palestine.

EUL MS 284

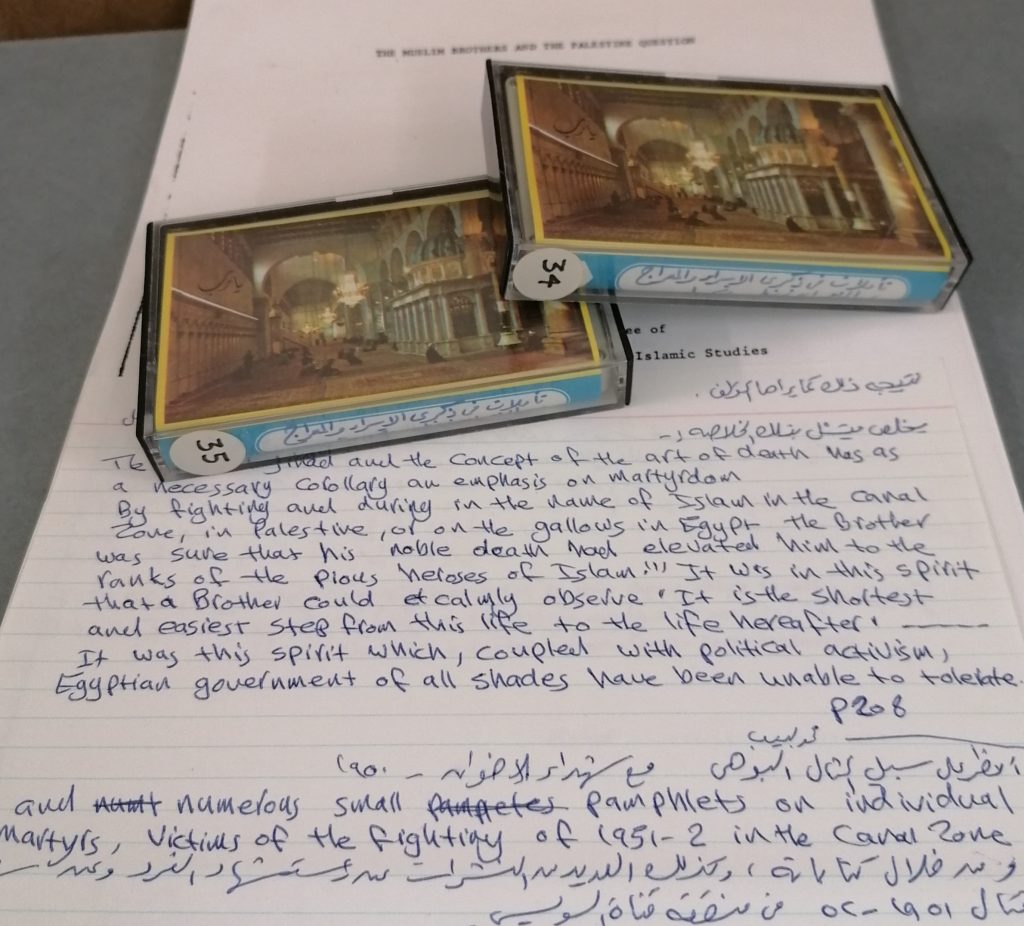

El-Awaisi’s account of this history was based on a wide range of Arabic sources from Egypt, Jordan and Palestine, both published and unpublished, as well as records from the Foreign Office. During the 1980s he also travelled to Geneva, Cairo and Palestine to conduct interviews with twelve former members of the Brotherhood, contemporaries of Hasan al-Banna who had been involved in the Palestinian resistance. These interviews were recorded and now form part of the El-Awaisi archive of almost 230 cassette tapes. In addition to the interviews, there are recordings of Islamic and Palestinian songs, a conference on Iran held by the Muslim Institute in London, lectures by Shaykh Fu’ad al-Rifai and Shaykh Ahmad al-Qattan, sermons by Palestinian cleric and militant Abu Anas on ‘Jarimat al-Watan al-Badil’ [‘The Crime of the Alternative Homeland proposal’], and over fifty tapes of the radical Jordanian MP and Muslim Brother Shaykh Abd al-Munim Abu Zant. The value of this audio archive extends far beyond the parameters of El-Awaisi’s PhD research, and will be of relevance for anyone researching the wider history of radical Islam. In addition to a card listing of the tapes’ contents, there are five boxes of index cards – written chiefly in Arabic – providing a subject index to El-Awaisi’s research materials, including book and periodical references. The tapes are in the process of being digitised, although this is a time-consuming practice that will take several months.

The aims, strategies and activities of the Muslim Brotherhood remain a highly contentious issue. Despite long-standing support from Qatar and Turkey, the Brotherhood has been designated a terrorist organisation by Egypt, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and Russia, and during 2019 Donald Trump called for the USA to do likewise. Although it officially renounced violence in the 1970s, the Brotherhood’s theocratic ideology can be seen to underpin the agendas of militant groups such as Hamas, al-Qa’eda and ISIS – even if the relationship between these groups ranges from, at best, informal collaboration to outright mutual condemnation – with the writings of Hasan al-Banna and Sayyid Qutb (1906-1966) playing a significant role in the development of Islamic fundamentalism. Even if the fullness of their commitment to democracy is debatable, the Brotherhood’s emphasis on social transformation, electoral participation and charitable work for the sick and the poor indicates that they may have much to offer as a nonviolent alternative to more extreme forms of Islamism.

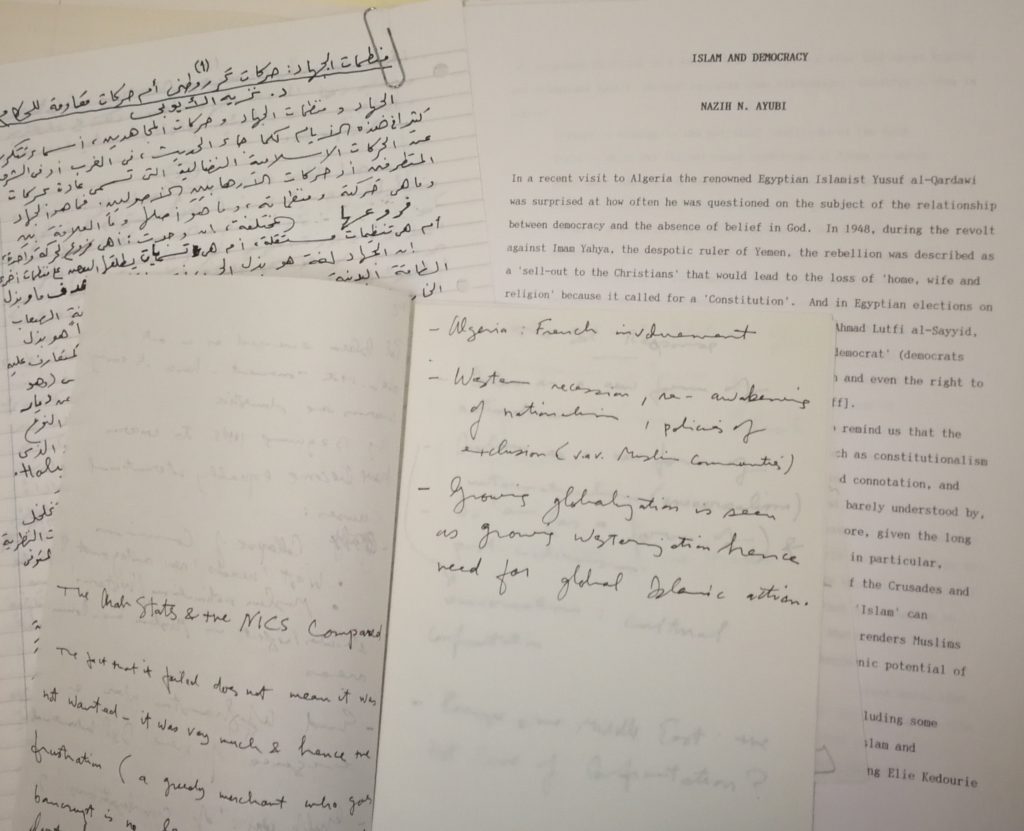

Using archival sources is a valuable step towards engaging with a complex and challenging debate such as this, as it encourages the enquiry to go beyond general abstractions (such as ‘The Clash of Civilisation’ trope) and examine primary sources that record the actual words, written and spoken, of individuals at a specific time and place. This is particularly important for anyone studying the Muslim Brotherhood and its various affiliate networks, which have often evolved in different ways according to regional and local contexts, and the political realities of the moment. In addition to the El-Awaisi archive – which has been catalogued here – there are sub-sections of the Ayubi papers dealing specifically with political Islam, Egypt and militant Islamic movements in the Middle East (EUL MS 129/1/2 and EUL MS 129/1/3, see records here) and also a small folder of manuscript notes in the Richmond papers on the 1966 trial in Egypt of Sayyid Qutb and other members of the Muslim Brotherhood (EUL MS 115/41/1, see here.)