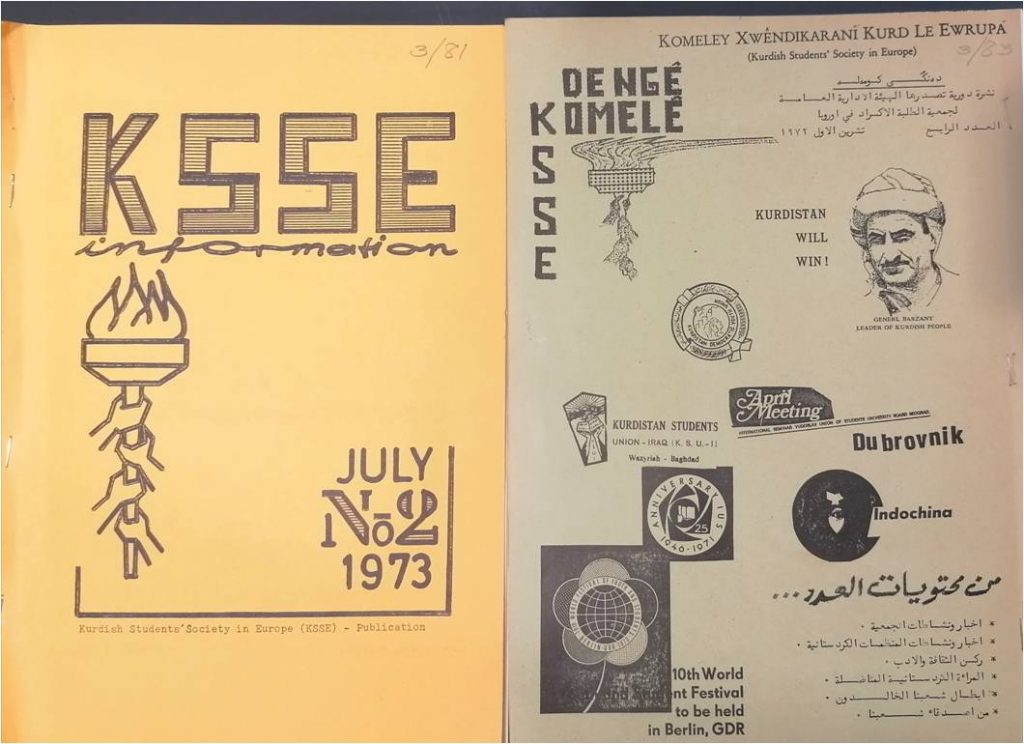

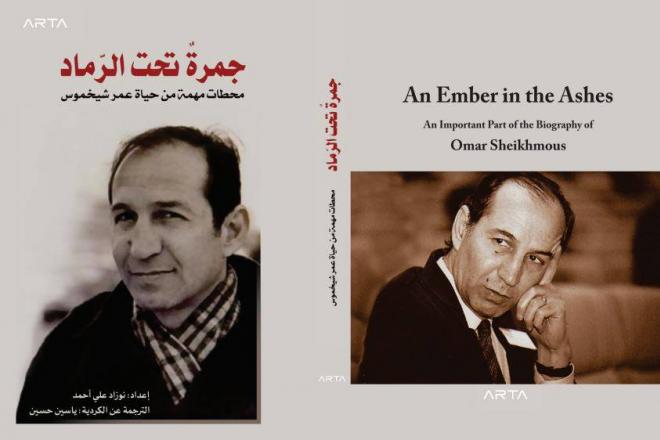

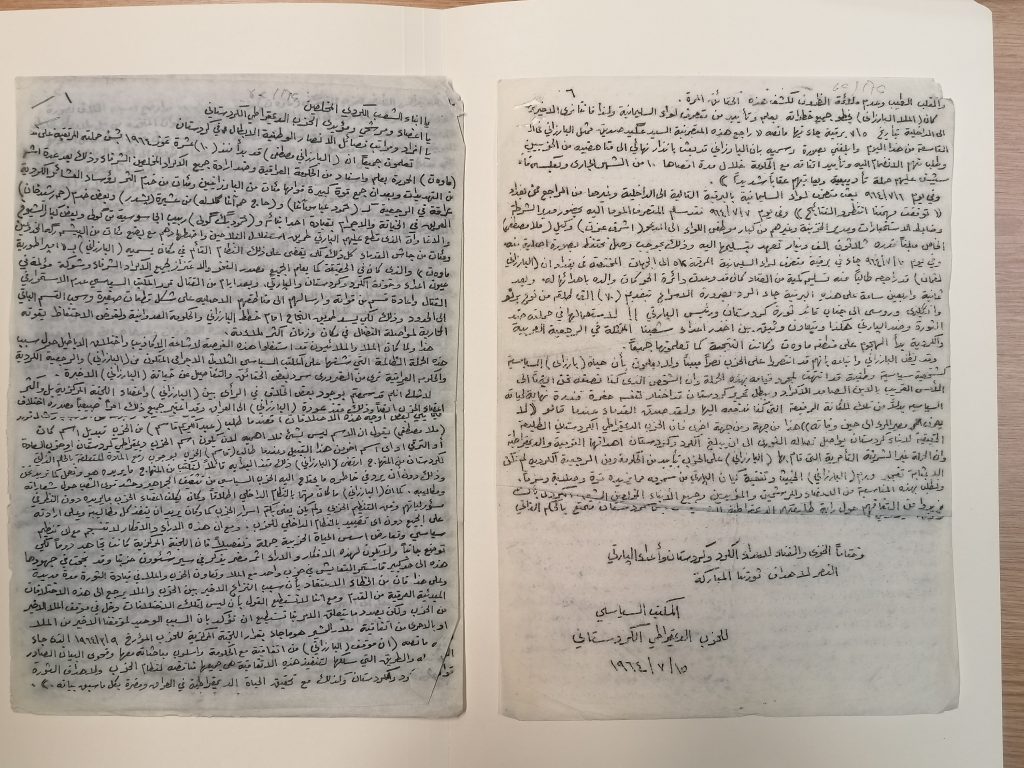

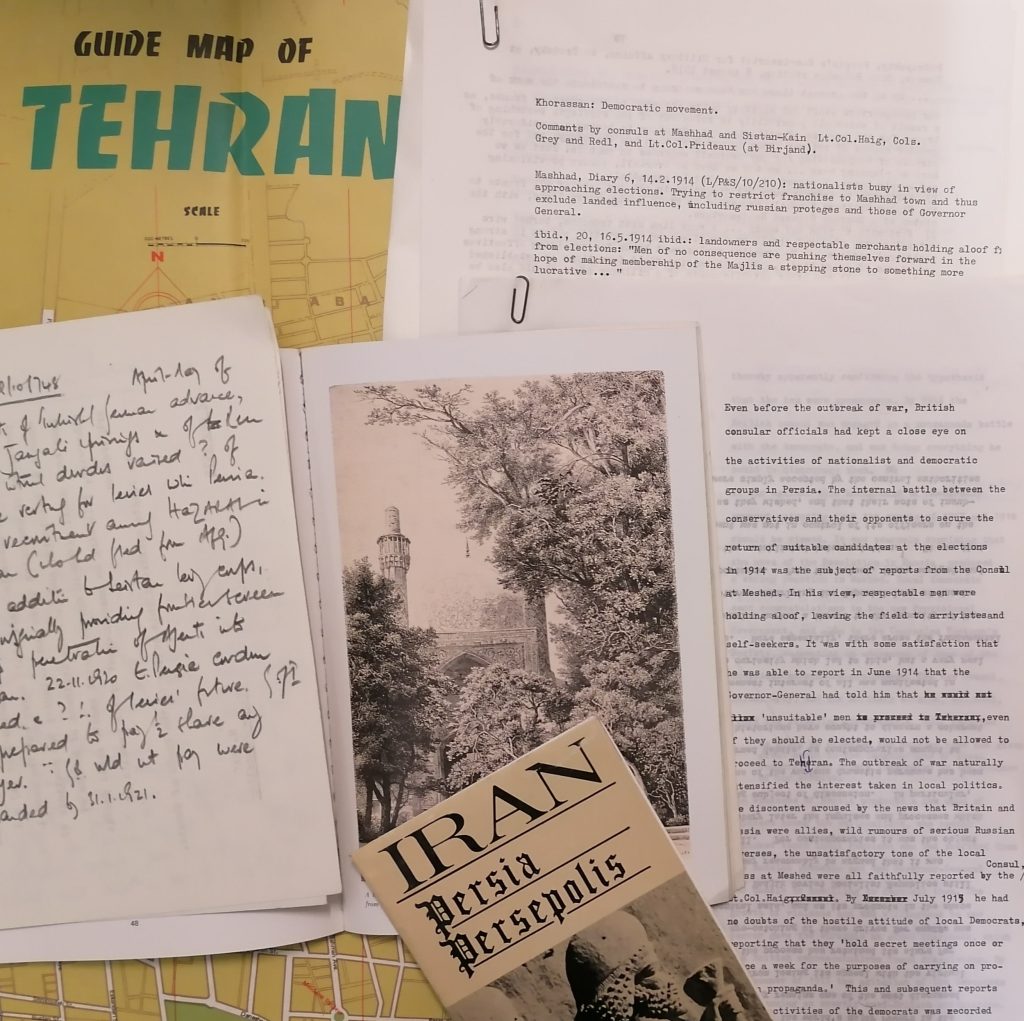

In the concluding entry to our series of blogposts exploring the Omar Sheikhmous archive, it seemed a good idea to provide a guide to the various Kurdish political parties, groups and movements for which he hold material in our collections. The complex and convoluted history of Kurdish resistance can be hard to follow, with multiple splits and reunions, confusing acronyms and variant forms of names.

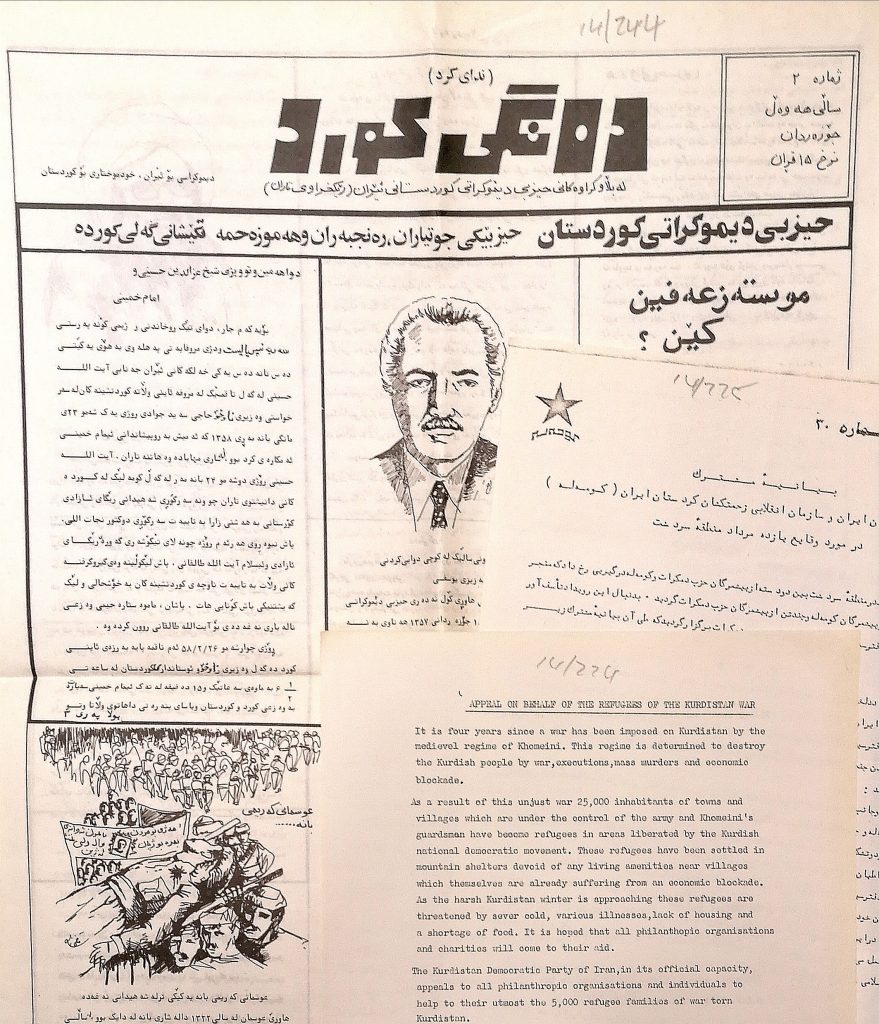

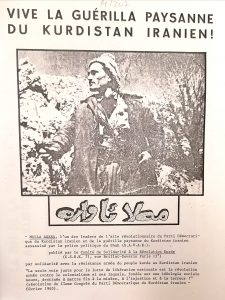

The party emblems and logos are all taken from documents in the Sheikhmous archive.

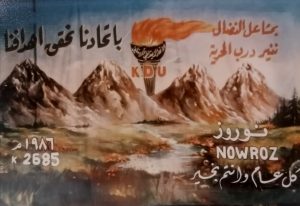

Democratic Party of Iranian Kurdistan (KDPI) – EUL MS 403/3/3

Kurdish Democratic Party of Iran

Hîzbî Dêmukratî Kurdistanî Êran

Persian: حزب دموکرات کردستان ایران

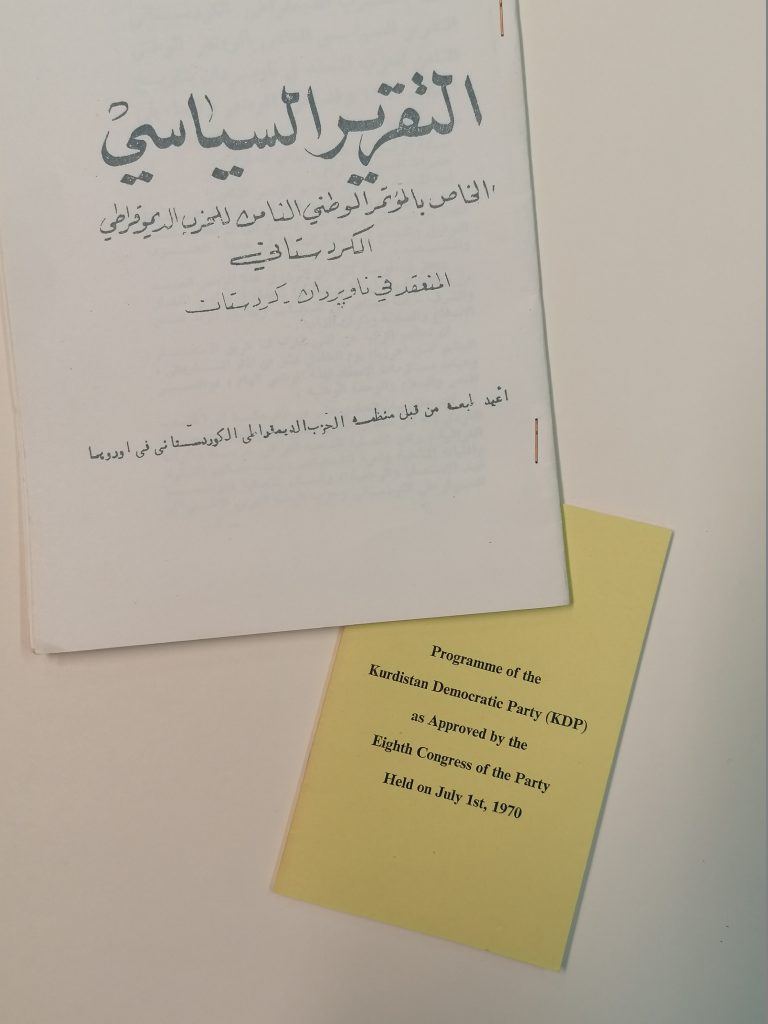

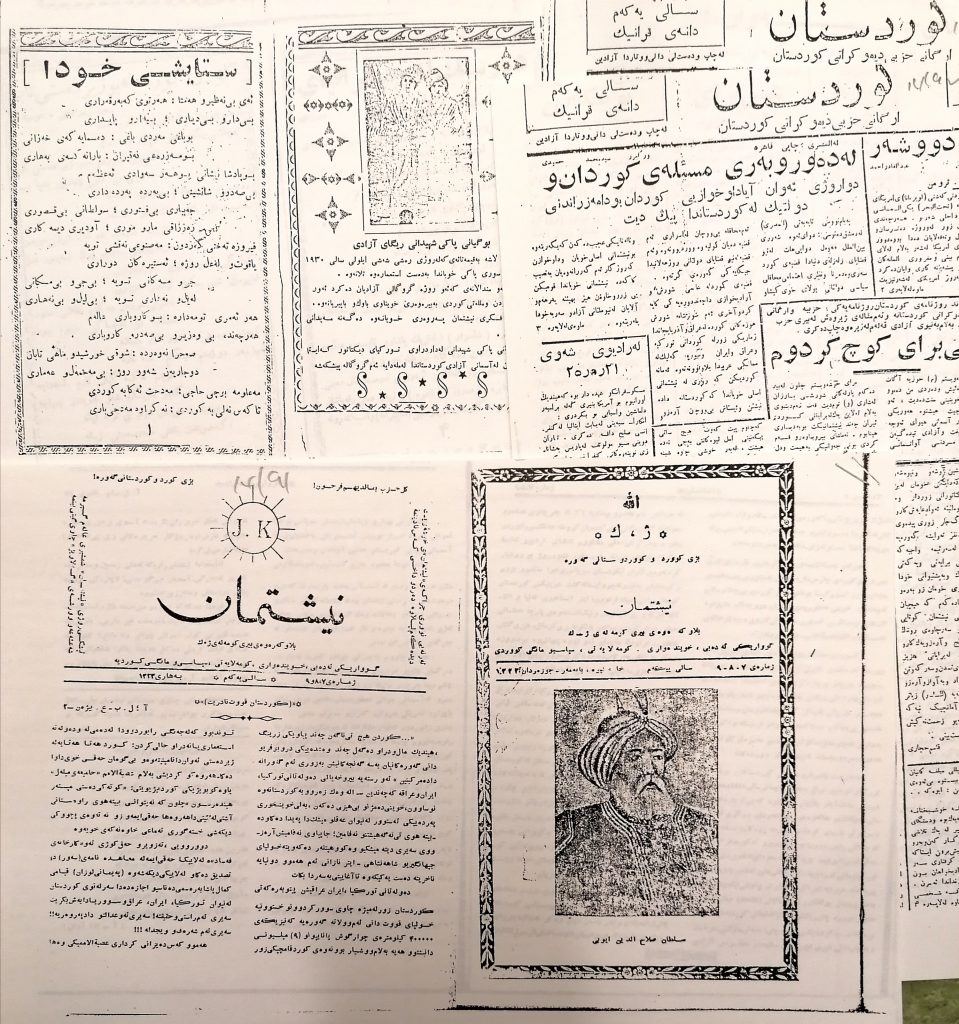

The Democratic Party of Iranian Kurdistan (KDPI) was founded by Qazi Muhammed in Mahabad in 1945, and we also hold a file on the short-lived Republic of Mahabad that includes copies of periodicals published there prior to Muhammed’s execution in March 1947 (EUL MS 403/7/1/1).

The subsequent repression of the party forced it to operate underground for the next few years, surfacing occasionally for short-lived collaborations in the 1950s and 1960s. When the new Islamic regime rejected calls for Kurdish autonomy, the KDPI joined other Kurdish groups to fight the Iranian government from 1979 to 1981, a conflict that continued intermittently ever since. The KDPI remains prescribed in Iran, with many of its members taking refuge over the border in Iraq.

Most of the material held dates from the 1980s, although there are documents dated between 1978 and 1996 in the file. These include information sheets, leaflets written by KDPI activists, bulletins, press releases, open letters from the KDPI leadership, issues of periodicals and newspapers such as Kurdistan: Organî Kumîtey Nawendîye Hîzbî Dêmukratî Kurdistanî Êran, ‘Talash dar rah-I tafahum: majmu’ah-‘i asnad and Kurdistan Today, along with personal correspondence such as invitations to meetings sent to Omar Sheikhmous.

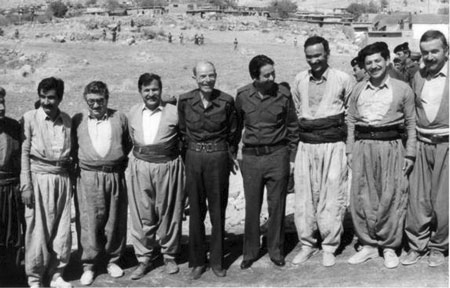

One of the most significant figures in the history of the KDPI is Abdul-Rahman Ghassemlou, who led the party from from 1973 until his assassination in Vienna in 1989. There are several official KDPI communications from Ghassemlou in the file, along with a separate correspondence file (EUL MS 403/2/1/4) and cuttings on Ghassemlou’s life and death (EUL MS 403/7/5). There is also an open letter written byGhassemlou’s successor as KDPI Secretary General, Abdullah Hassanzadeh, on the subject of Iranian state terrorism with a four page list of victims and a statement about Iranian cleric and intelligence minister Ali Fallahian in relation to the ‘Mykonos’ murder of Kurds in Berlin (1996)

Komala – EUL MS 403/3/4

Society of Revolutionary Toilers of Iranian Kurdistan

Komełey Şorişgêrî Zehmetkêşanî Kurdistanî Êran

Revolutionary Workers’ Society of Iranian Kurdistan / ‘Society of Revolutionary Toilers of Iranian Kurdistan’

كۆمهڵهی شۆڕشگێڕی زهحمهتكێشانی كوردستانی ئێران كۆمهڵهی شۆڕشگێڕی

[NB Not to be confused with the Kurdistan Toilers’ Party, (KTP) Hizbi Zahmatkêshani Kurdistan, or Hizb al-Kadihin al-Kurdistani, which was founded in 1985 and publishes newspapers and periodicals including Alay Azadi (Banner of Freedom), Pesh Kawtin and Nojan.]

Komala means ‘group’ or ‘society’ in Kurdish, and the recurring use of the word in the names of several different political groups can be confusing.

Emerging from a student organisation in the late 1960s, the Komala party took formal shape in the late 1970s as Komełey Şorişgêrî Zehmetkêşanî Kurdistanî Êran [in Kurdish] or ‘Society of Revolutionary Toilers of Iranian Kurdistan’ until 1984 when it became the Komala Kurdistan’s Organization of the Communist Party of Iran. It remained part of the Communist Party of Iran until 2000 when one of its leaders, Abdullah Muhtadi, led a breakaway faction named the Komala Party of Iranian Kurdistan (Komala-PIK). Two further schisms occurred in 2007 and 2008, resulting in the creation of other Komala splinter groups led by Omar Ilkhanizade and Abdulla Konaposhi respectively.

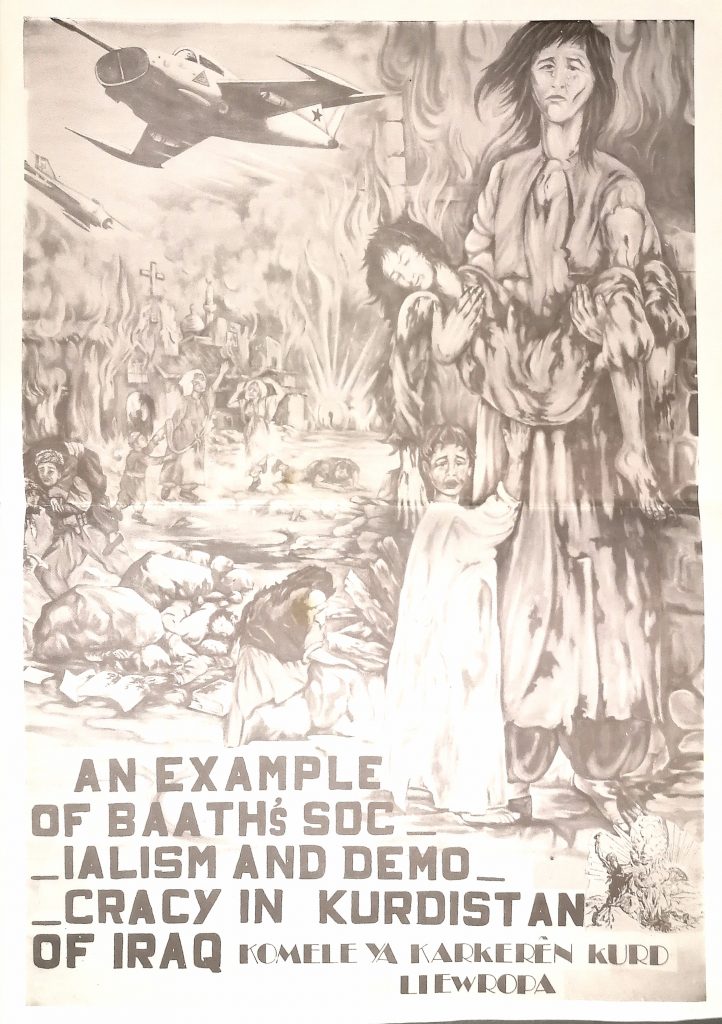

The material we hold – which includes leaflets, press-releases, posters and booklets – spans the period between 1965 and 2009 and includes publications issued by Komala, the Communist Party of Iran and various international branches such as the Organisation of Komala Supporters Abroad.

Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK) – EUL MS 403/3/5

Partiya Karkerên Kurdistanê

The PKK was founded in November 1978 in the village of Fis (near Lice), by a group of Kurdish students led by Abdullah Öcalan. During the 1980s and 1990s it was engaged in violent conflict with the Turkish state and military authorities, but in 1999 Öcalan was captured and imprisoned, and since then he has been held in solitary confinement as the only prisoner on İmralı island in the Sea of Marmara.

We don’t hold many PKK documents but there is a large amount of secondary material on Öcalan and PKK activities in the box on the Kurds in Turkey (EUL MS 403/7/6/4), a biographical file on Öcalan (EUL MS 403/7/5) and numerous news reports in Boxes EUL MS 403/10, including statements about the PKK issued by Jalal Talabani.

Komkar EUL MS 403/3/7

The Association of Kurdish Workers for Kurdistan

Federasyona Komelên Karkerên Kurdistan [Komelên Karkerên = Kom Kar]

Among the Kurdish diaspora, it was students who were the first to start forming political organisations, beginning with the Kurdish Students Society in Europe (KSSE). In 1979 groups of Kurdish workers in Turkey came together to form ‘Komkar’, and this federation of Kurdish worker’s associations soon become widely established across Europe.

We hold papers from various European Komkar branches including statements on Kurdish and Turkish affairs, information on the 5th Komkar congress in 1983, correspondence, posters and publications.

Kurdistan Socialist Party – Iraq and related Socialist parties

EUL MS 403/3/8 and EUL MS 403/3/20

Kurdistan Socialist Party – Iraq (KSP-I)

الحزب الاشتراكي الكردستاني العراق

al-Ḥizb al-Ishtirākī al-Kurdistānī – al-`Irāq

Partiya Sosyalist a Kurdistan (PSK or PASOK)

al-Hizb al-Ishtiraki al-Kurdi

The complicated history of the different Socialist parties involved in the Kurdish struggle requires some careful unpicking. The United Socialist Party of Kurdistan was formed in 1979 when a former KDP splinter group led by Mahmud Osman united with another group led by Socialist politician Rasul Mamand (1944–94). It was renamed the Socialist Party of Kurdistan-Iraq (KSP-I) in 1981. The party was dissolved in December 1992 when Mamand joined the PUK’s Political Bureau.

In 1993 the KSP-I was revived by a former member Mohammed Haji Mahmoud after he left the KDP, and at its second party congress the following year it changed its name to the Kurdistan Social Democratic Party (Parti Sosialiri Dimuqrati Kurdistan, Al-Hizb al-Ishtiraki al-Dimuqrati al-Kurdistani) – which is not to be confused with the Kurdish Socialist Democratic Movement which was founded in May 1976 by Salih Al-Yousify (1918-81) from which we have a copy of a document issued in 1977.

Meanwhile in Turkey the Socialist Party of Turkish Kurdistan (SPTK) had been founded in 1974 by Kemal Burkay. The activities of the party were disrupted by the coup in 1980, with Burkay and most of its leaders forced into exile, and at the congress in 1992 it changed its name to the Socialist Party of Kurdistan.

We have a small file on the SPTK (EUL MS 403/3/20) but the folder at EUL MS 403/3/8 contains material relating to both the KSP-I and the PSK, as well as the KSDP, including party newsletters and periodicals such as Peyamî Birayetî, Rebazi-Lawan, Regay Azadi (KSP-I), Surîn and Yekgirtin (PSK), draft documents, memoriam posters, military bulletins, correspondence including an invitation from Kemal Burkay and a handwritten letter to Omar Sheikhmous from the Kurdish Socialist Party in Syria, plus various documents from the Socialist International congresses in which Jalal Talabani and other Kurds participated.

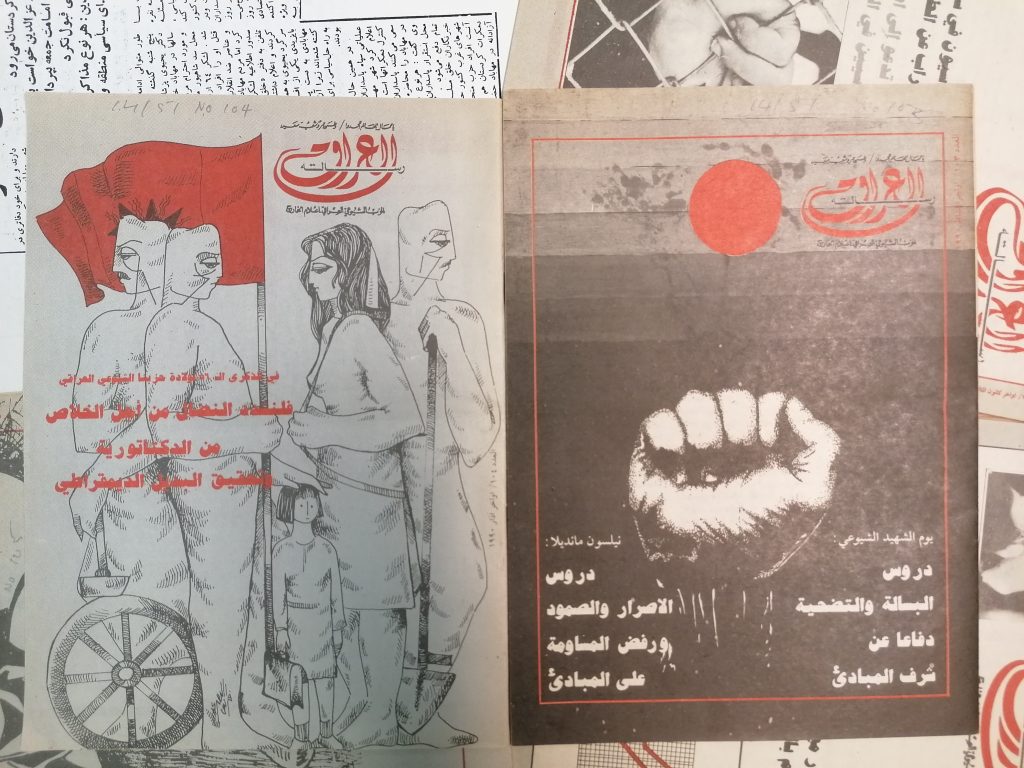

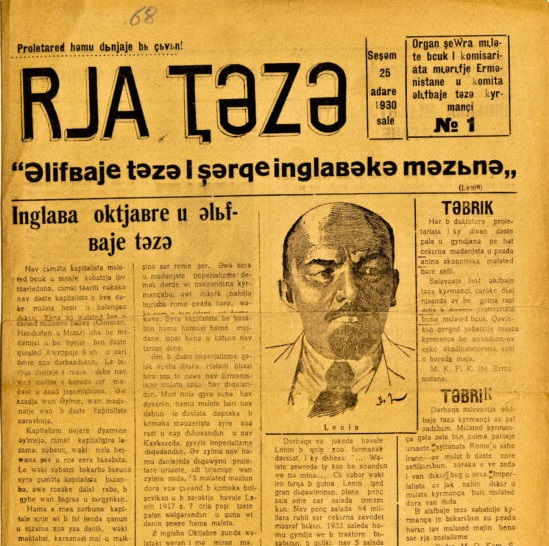

Iraqi Communist Party – EUL MS 403/3/9

Title page of the ICP newspaper Ṭarīq al-shaʻb

Arabic: الحزب الشيوعي العراقي

[al-Hizb al Shuyu’i al-Iraqi]

The Iraqi Communist Party was founded in 1934, emerging out of organised boycott of the British-owned Baghdad Electric Light Company. After various vicissitudes during the 1940s, it was strengthened in the early 1950s by growing support from Kurds, who gradually took over leadership roles and influenced the ICP’s approval of the principle of Kurdistan’s autonomy in their 1953 charter. Following the 1963 Baathist take-over, however, the ICP faced severe oppression from the government, and in 1967 a breakaway group (led by Aziz al-Hajj, who died earlier this year) split from the ICP and established the Iraqi Communist Party – Central Command. Weakened by the division, the ICP activities gradually focussed more on Kurdish areas and less on Baghdad. The close associaton between the Kurds and the ICP is reflected in the fact that a Kurd, Aziz Muhammad (1924-2017) was Secretary General of the ICP from 1964 until 1993.

Most of the material in this file comes from the late 1970s and the 1980s and includes several issues of ICP periodicals and newspapers such as Ṭarīq al-shaʻb and Rêyazi Pêshmerge, numerous documents on relationships with other parties, including the KDP and the PUK, the Tudeh Party in Iran, as well as other branches of the Communist Party, articles on a range of topics written by ICP members, letters, party reports and press releases.

There is also a smaller file containing seven documents relating to the Workers Communist Party of Iraq (WCPI), [in Arabic: الحزب الشيوعي العمالي العراقي or al-Hizb al-Shuyu’i al-Ummali al-Iraqi, and in Kurdish: Hizbi Communisti Krekari Iraq] which was founded in 1993.

Political Alliances and Coalitions

The history of the Kurdish resistance movement has, tragically, been characterised by a great deal of in-fighting and self-destructive rivalry, by there have also been several successful attempts to bring together political groups under umbrella organisations that could consolidate opposition and strengthen cross-party collaboration. Although these alliances may not always have lasted long, they were significant steps in the development of the Kurdistan Regional Government.

Democratic National Patriotic Front in Iraq – EUL MS 403/3/12

This was an umbrella opposition group founded in November 1980 and consisting of the Iraqi Communist Party, the National Union of Kurdistan and other parties. The file contains four documents, including letters to Omar Sheikhmous from the DNPF leadership (1982-83) and an information sheet (1987)

This was an umbrella opposition group founded in November 1980 and consisting of the Iraqi Communist Party, the National Union of Kurdistan and other parties. The file contains four documents, including letters to Omar Sheikhmous from the DNPF leadership (1982-83) and an information sheet (1987)

Iraqi Kurdistan Front EUL MS 403/3/13

The Iraqi Kurdistan Front (IKF) was formed in 1987-88 from the PUK, KDP and six smaller parties – including the KPDP, the KSP-I and PASOK – with the aim of uniting Kurdish factions and strengtheing opposition to the regime in Baghdad. The IKF played a major role during the ‘National Uprising’ of 1991 following the Gulf War ceasefire, as well as preparations for the general elections on 19 May 1992.

Documents include letters and proposals for the formation of the IKF, the first issue of their newspaper Berey Kurdistanî (September 1989) and joint statements by Jalal Talabani and Masoud Barzani regarding the forthcoming elections (1992). The IKF subsequently broke up, in part due to the ongoing tension between the KDP and the PUK.

Kurdistan National Congress – EUL MS 403/3/6

Kongreya Neteweyî ya Kurdistanê (KNK)

كۆنگرەی نەتەوەیی كوردستان

Kongreya Niştimanî ya Kurdistanê (KNK)

The Kurdish National Congress is a coalition of exiled Kurdish politicians and activists that was founded in 1999 following an initiative by the PKK that began in 1985, and absorbed the former Kurdistan Parliament in Exile.

The KNK’s first president was Ismet Cheriff Vanly (we hold a correspondence file of Vanly’s letters at EUL MS 403/2/13), who had served on the Executive Council of the previous body, and we have various documents relating to the dissolution of the Kurdistan Parliament in Exile and the draft charter for the KNK, as well as correspondence, press releases and publications.

Iraqi National Congress – EUL MS 403/3/17

المؤتمر الوطني العراقي

al-Mu’tamar al-Watani al-‘Iraqi

The history of the Iraqi National Congress is closely associated with the controversial figure of Ahmad Chalabi (1944-2015). Founded in Vienna in June 1992 as an umbrella organisation of Kurdish, Sunni and Shi’a groups opposed to Saddam Hussein’s government, the INC was comprised mainly of Kurdish exiles but received funding and support from the US government, including the CIA. Over the following decade, Chalabi and others associated with the INC played a significant role in encouraging the development of the US government’s neoconservative foreign policy towards Iraq that resulted in the 2003 invasion and the demise of Saddam Hussein.

The file includes papers from the 1992 INC congress, including a transcript of Jalal Talabani’s speech to the Opening Session, as well as a list of members of the INC, letters from Chalabi to various diplomats, press releases and documents relating to the INC’s involvement in the INDICT campaign for the prosection of Iraqi war criminals (1997).

The Independence Party of Kurdistan – EUL MS 403/3/10

Partîkarî Serbexoyî Kurdistane

The Kurdistan Independence Party was founded in Sweden between 1986 and 1989, and was dedicated to non-violent and democratic means of achieving independence for Kurdistan.

Amir Qazi (or Ghazi), Chairman of the Independence Party, was a former member of the politburo of the KDPI and married Efat (1935-1990), the daughter of Qazi Muhammad, president of the Kurdish Republic of Mahabad. She was killed in Sweden by a letter bomb addressed to her husband, and thought to have been sent by Iranian agents. The folder contains a letter from Qazi, several issues of their periodical ‘Ala’ (1986-), documents and press-releases.

Revolutionary parties – EUL MS 403/3/11

The Revolutionaries Union of Kurdistan

Yekêtî Sorisgirani Kurdistan

The Kurdish Revolutionary Party

الحزب الثوري الكردستاني

al-Hizb al-Thawri al-Kurdistani

Hizbi Shorishgeri Kurdistan

The Kurdish Revolutionary Party was founded in 1964, before temporarily merging with the KDP (1970-72) and then being revived by members who were unhappy with the KDP leadership. In 1974 it joined the Ba’ath Party approved National Progressive Front (NPF) and consequently lost much of its significance. The file includes the constitutions from 1964 and papers from the party congress in 1970 concerning its relationship with the KDP.

The Revolutionaries’ Union of Kurdistan was founded in May 1991 by an Iranian Kurd, Said Yazdanpanah, who was assassinated five months later. The organisation was then led by his brother Hussein. At a party congress in 2006 it was renamed the Kurdish Freedom Party [پارتی ئازادیی کوردستان] and Ali Qazi – brother of Efat, mentioned above – was elected leader.

None of these parties should be confused with Yekêtî Şorişgirani Kurdistan [Revolutionary Union of Kurdistan], which was a faction within the PUK formed around 1982 by an alignment with some Socialist groups. The file holds several letters to and from this group, with correspondents including Omar Sheikhmous, Omar Dababa, Fuad Masoum and Kemal Fuad, as well as membership booklets and other documents.

Kurdistan Democratic Progressive Party in Syria – EUL MS 403/3/16

Partiya Dîmoqratî Pêşverû Kurd li Sûriyê

Partiya Dîmoqratî Pêşverû Kurd li Sûriyê

Al-Hizb al-Dimuqrati al-Kurdi al-Taqaddumi fi Suriya

الحزب الديمقراطي التقدمي الكردي في سوريا

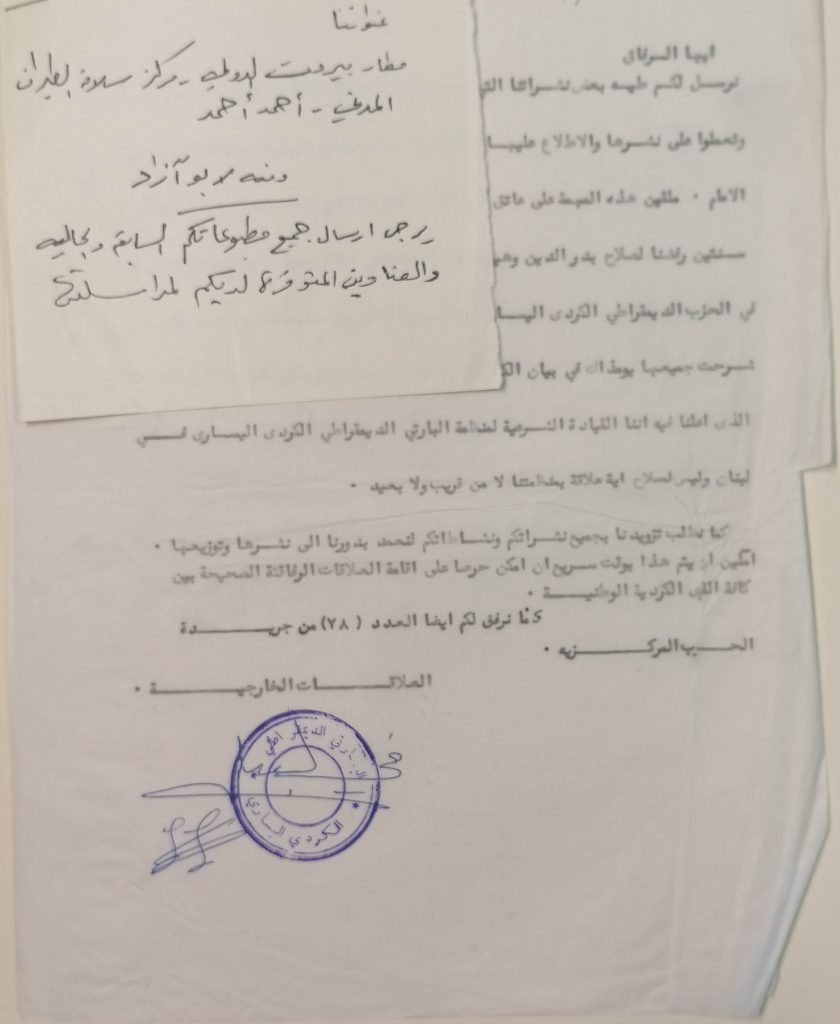

The history of the KDPPS is inseparable from the life of its leader, the late Abdul Hamid Darwish (1936-2019), who was one of the co-founders (along with Nûredein Zaza and Osman Sabri) of the Kurdistan Democratic Party of Syria in 1957. Internal disagreements led to the KDPS splitting in 1965, with Darwish leading the more moderate and conciliatory group that became known as the Kurdistan Democratic Progressive Party. Over time the KDPPS came to align itself closely with Jalal Talabani’s PUK, while the KDPS aligned itself with Mustafa Barzani’s KDP, which would have a negative impact upon the two Syrian parties’ relations as the rivalry between the KDP and PUK developed into armed conflict.

Within Syria, however, the KDPPS continued to play an important role in both national politics and Kurdish affairs, with Darwish being elected to the Syrian parliament in 1990 and helping to establish relations between the Kurdish National Council and Syrian opposition groups. Papers in this file are dated between 1977 and 1999 and include numerous copies of the party’s newspaper al-Dimuqrati, a proclamation on the war between Kurds in Iraq and the Iraqi regime (1988), as well as documents and press-releases from the mid-1990s.

Kurdistan Popular Democratic Party (KPDP) – EUL MS 403/3/18

Hizb al-Sha’ab Dimuqrati al-Kurdistan

Hizb al-Sha’ab Dimuqrati al-Kurdistan

Parti Geli Dimukrati Kurdistan

The Kurdistan Popular Democratic Party (KPDP) was founded by Sami Abdulrahman in 1979 as a breakaway group from the KDP, which they rejoined in 1993.

Documents include various bulletins and statements issued by the party (1981-85), a list of fifteen KPDP members executed in Mosul in 1985, a supplement to the KPDP periodical ‘Gel’ on the General Scientific Conference of Kurds in the Soviet Union (1990), a photocopy of the first page of issue no 40 of Gel [ al-Sha`b], Document from the 2nd conference (1990)

Kurdistan Democratic Union – EUL MS 403/3/21

Yeketi Dimukrati Kurdistan

al-Ittihad al-Dimuqrati al-Kurdistani

The Kurdistan Democratic Union (KDU) was founded by Ali Sinjari in 1977 but was later merged with the KDP in 1993. Documents in the file include a news bulletin (1986), a leaflet Reya Yeketiye (1987), an Arabic press release published in June 1991 to mark the 14th year of the founding of the party and issue no.20 (October 1990) of the KDU periodical Al Sha’lah/Mesxel .

The National Democratic Union of Kurdistan (Yekitiya Netewayî Demokratî Kurdistan, or YNKD) was founded in 1995 by Ghafur Makhmuri – the folder contains a press release issued on 15 November 1995.

The Sheikhmous archive does include hold material relating to other political parties and movements, and there also folders containing papers from left-wing Iranian parties as well as Islamic political groups and other bodies, such as the Association of Kurdish Doctors in Europe.

The Sheikhmous papers have now been catalogued and the entries can be consulted here.

This was an umbrella opposition group founded in November 1980 and consisting of the Iraqi Communist Party, the National Union of Kurdistan and other parties. The file contains four documents, including letters to Omar Sheikhmous from the DNPF leadership (1982-83) and an information sheet (1987)

This was an umbrella opposition group founded in November 1980 and consisting of the Iraqi Communist Party, the National Union of Kurdistan and other parties. The file contains four documents, including letters to Omar Sheikhmous from the DNPF leadership (1982-83) and an information sheet (1987)

Partiya Dîmoqratî Pêşverû Kurd li Sûriyê

Partiya Dîmoqratî Pêşverû Kurd li Sûriyê Hizb al-Sha’ab Dimuqrati al-Kurdistan

Hizb al-Sha’ab Dimuqrati al-Kurdistan