The Al-Azmah papers are unusual amongst our collections in that they document the political careers of two brothers, both of whom – in related and overlapping spheres of activity – played a major role in the development of Arab nationalism in the Middle East. Although much of their lives were spent in their native Syria, the Al-Azmah brothers were active across Palestine and Transjordan and also held important political positions in the Syrian government during the eras of the French mandate as well as postwar independence.

Nabih and Adil were was born in Damascus to Abdel Aziz Al-Azmah, and belonged to a distinguished Damascene family who traced their origins back several centuries to Hasan Bey al-Azma, a Turkmen military leader who had settled in Syria. Many family members attained prominent positions in Syria as merchants, landowners, administrators, military and political leaders, as well as in the arts and sciences. These include Nabih and Adil’s uncles, Zaki, Taher and Yusuf Al-Azma, who were all respected army officers, Bashir al-Azma (1910–1992), who was briefly Prime Minister of Syria in 1962, Malak al-Azma, a successful banker whose son Professor Aziz al-Azmeh, donated the papers of his grandfather and great-uncle Adil and Nabih to the University of Exeter.

نبية العظمة Nabih Al-Azmeh (1886-1972)

Nabih was educated at the Al-Rashdiya Military School in the Yalbugha Mosque in the Al-Bahsa neighborhood of Damascus before travelling to Yemen at the age of twelve where his father had been appointed as an administrator in the Hodeidah district. After returning from Yemen, he joined the Istanbul Military Academy in 1905, graduating two years later with the rank of lieutenant. He took part in the war in Libya against the Italian military invasion (1911-13) and during the First World War he fought with the Ottoman forces, taking part in the attack on the Suez Canal in 1915 as well as the campaign in Palestine.

Following the collapse of the Ottoman empire at the end of the war, the British took control of Palestine, Iraq and Transjordan, while France took over Syria in 1920. King Faisal was appointed head of the Arab Kingdom of Syria in March 1920 and during his short reign Nabih Al-Azmah served as director of police in Aleppo, while his uncle Yusuf Al-Azmah was Minister for War. However, in April 1920 the League of Nations gave France a mandate over Syria. A few Syrians were prepared to accept French rule, but the majority were strongly opposed to the idea and Yusuf Al-Azmah was one of the foremost advocates of armed resistance. When the French invaded with a force comprising several thousand troops, supported by tanks, artillery and aircraft, Yusuf died a heroic death in the Battle of Maysalun in July 1920. The Arab government in Syria was dissolved and King Faisal was expelled from Syria, although the following year the British had him installed as King of Iraq, an office he fulfilled until his death in 1933.

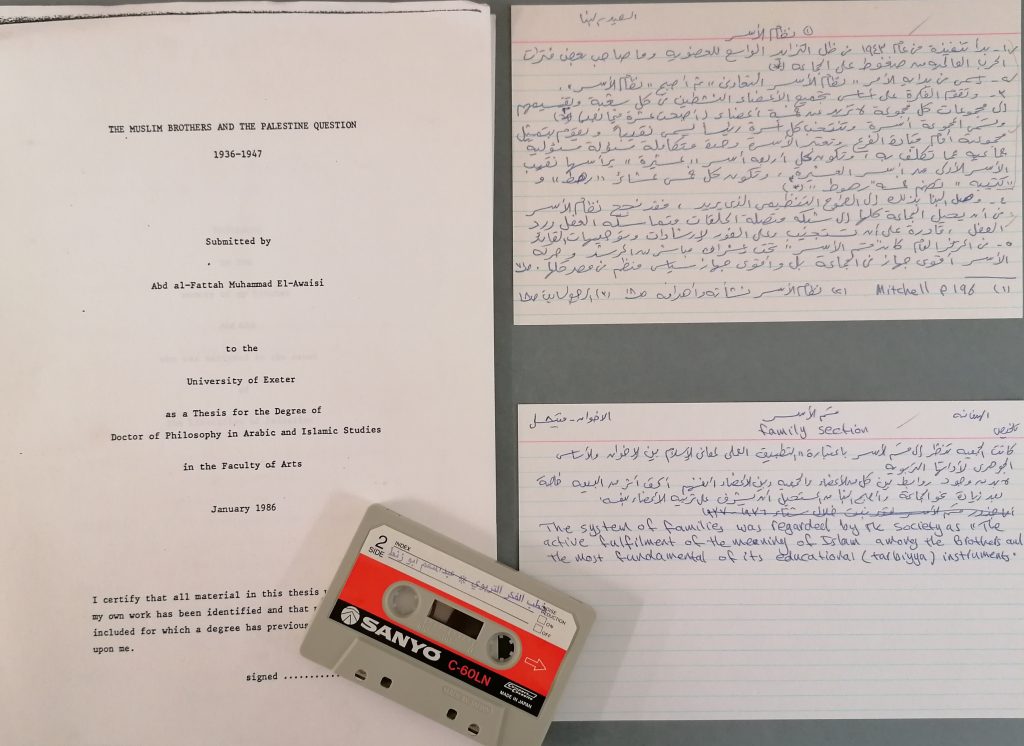

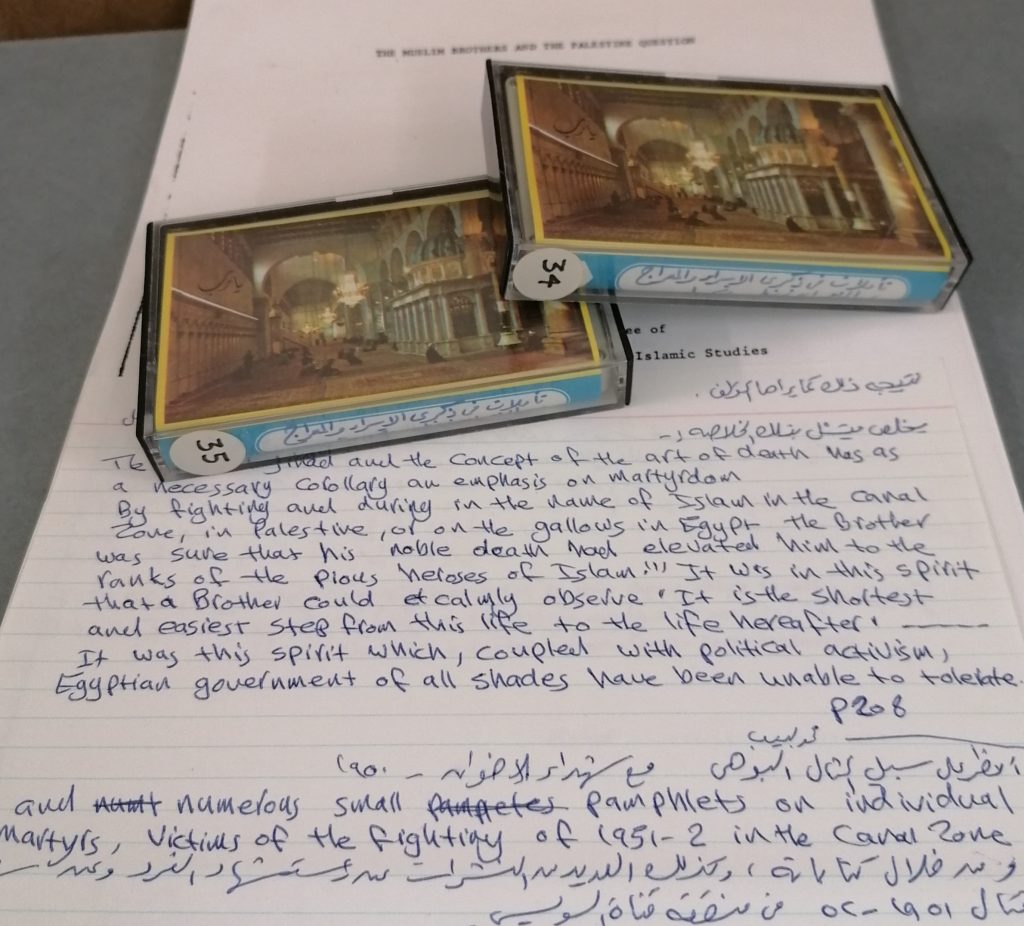

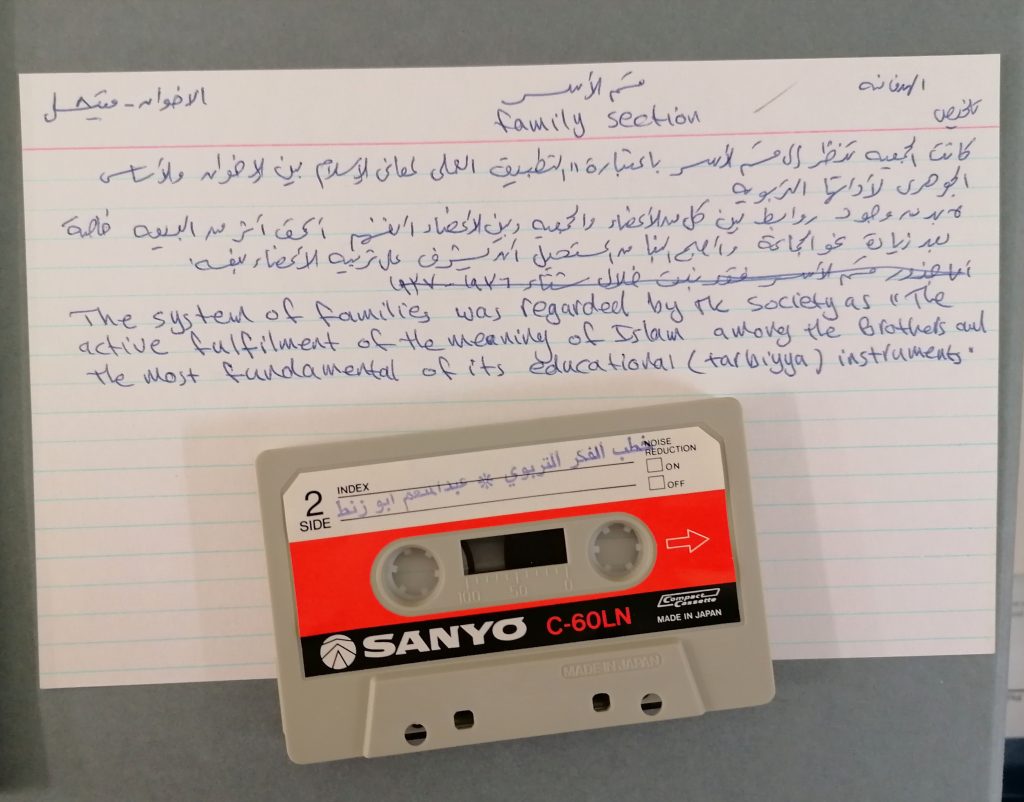

Following the death of his uncle and the French take-over of Syria, Nabih Al-Azmah left Syria and remained in exile for the next two decades. He moved first to the Druze city of as-Suwaydā’ in southwestern Syria, close to the border with Jordan, and then took up a role as advisor to King Faisal’s brother, Prince Ali bin Al Hussein, the Emir of Jordan. He later worked with Ibn Saud in establishing and training a modern army for the emerging Saudi nation. During the 1930s he was active in Palestine, beginning with the Islamic Conference in Jerusalem December 1931, which had been organised by the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, Hajj Amin al-Husayni (1895–1974) and Indian Pan-Islamist Shawkat ‘Ali (1873–1938) and reflected the growing interest of Muslims in Palestine and the threat of Zionism – a topic explored in depth in the archive of Abd al-Fattah Al-Awaisi (EUL MS 216). Although Nabih Al-Azmah knew the Grand Mufti (who was also a friend of Ernest Tatham Richmond) – there are photographs of them together during this period – and other Islamic personalities active in the region, the main focus of the Al-Azmah brothers was on Arab nationalism.

Cover of a pamphlet published by the Hizb al-Istiqlal al-Arabi (Arab Independence party) in 1932 EUL MS 215/7/6

In 1932 he helped establish Palestine’s first political party, Hizb al-Istiqlal, modelled in part on the Syrian nationalist party Hizb al-Istiqlal al-‘Arabi to which he belonged. The following year he was appointed director of the first Arab Exhibition, held in Jerusalem, and he continued in this role for the second Exhibition in 1934.

Al-Azmah also participated in the Great Revolt of 1936-39, a nationalist uprising by Palestinian Arabs against the British administration of the Palestine Mandate. He became head of the ‘Committee for the Defense of Palestine’, providing support and assistance between the mujahideen in Syria and those in Palestine. As head of the Syrian Palestine Defence Committee he attended the General Arab Congress at Bludan in 1937, which strove to strengthen Pan-Arab feeling in the region in support of Palestine.

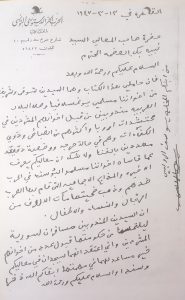

Letter from Fawzi al-Qawuqji , Commander of the Society for the Defense of Palestine. EUL MS 215/10/1

Like al-Husayni, Al-Azmah’s opposition to the British and the French led him to consider supporting the Nazis during the Second World War, on the basis of ‘my enemy’s enemy must be my friend’, but unlike some other Arab nationalists he remained very wary of such an alliance; after some initial contact with Axis forces, he withdrew all ties. When the Allied forces arrived in Syria in 1941 he was forced once more to go into exile in Istanbul. After the war Nabih returned to Syria where he was appointed Minister for Defence in the new independent government of Saadallah Al-Jabri. This only lasted for a brief period, after which he held the position of Chairman of the National Party until his retirement in the early 1950s. He died in 1972.

Conference pamphlet published by the League of Nationalist Action. EUL MS 215/7/6

عادل العظمة Adil Al-Azmeh (1888-1952)

Portrait of Adil Al-zmah, from a newspaper report on his death EUL MS 215/6/2

Adil did not share his older brother’s military background, but he was equally active in his work for Arab nationalism. He graduated from law school in Istanbul and practised for some time as a lawyer in the early 1920s before joining Nabih in Transjordan, where he campaigned against Jewish immigration into Palestine. Following the failure of the Great Revolt he was one of many Arab nationalists, led by the Grand Mufti, who took refuge in Iraq and supported the pro-German coup d’etat in March 1941. Adil relocated to Sofia but also seems to have spent some time in Iraq in the early 1940s. After independence, he occupied various posts of government, including Governor of Latakia (1944-46?) – during which time he played a role in the arrest and execution of Sulayman al-Murshid – Governor of Aleppo (1946-49), Minister of the Interior and Minister of State in two separate cabinets. The archive contains copies of his diaries for the years between 1946 and 1948 (EUL MS 115/1/11-14), providing a fascinating glimpse into his political and administrative duties. He died of pneumonia in Beirut in 1952.

EUL MS 215/5/4

Cover of a booklet published by the Governorate of Aleppo in 1947, with an image showing the city’s famous Bab al-Faraj Clock Tower and – in the distance – the 13th century citadel. EUL MS 215/5/4

Although these papers are all photocopies – the original documents are held in Damascus, with the Saudi papers now housed at the Darat al-Malik Ábd al-Áziz in Riyadh – they provide a wealth of information on topics such early Arab nationalism, political networks in the Levant, the activities of Islamic movements in Palestine, and the history of Syria during the transition from the French Mandate to independence. The documents include political correspondence with Arab leaders and key figures such as Fawzi Al-Qawuqji, Hashim al-Atassi, Fakhri el-Nashashibi, Rashid Rida, Mohamed Ali Ettaher, Asad Daghir, Wajih Al-Haffar, Dr Abd al-Rahman al-Kayyali, Muhammad ‘Izzat Darwazeh and others, state papers, political manifestoes and conference booklets for various political parties, as well as campaign material directed against the French administration in Syria and the British administration in Palestine. There are four indexes to the papers (EUL MS 215/6/4, 215/8/8, 215/11/3 and 215/12/13, which should probably be the starting point for researchers seeking to work with the collection.

The catalogue entries for the Al-Azmah papers can be consulted here