Iran – known as Persia until the middle of the 20th century – is the second largest country in the Middle East, after Saudi Arabia, and is also home to one of the world’s oldest civilisations, possessing an unbroken history that stretches back over six thousands year. In addition to the ancient ruins of Persepolis – one of nineteen UNESCO World Heritage Sites in the country – it is home to the Zoroastrian Towers of Silence, the Sheikh Safi mausoleum in Ardabil, the architectural wonders of Isfahan and the Golestan Palace, as well as the natural beauties of Mount Tamarvand – the highest peak in the Middle East – the forest and waterfalls of Gilan, and the magnificent rolling green plains of Torkaman Sahra. Much of the country comprises mountains and desert, which has hindered both invasion from the outside and expansion from within.

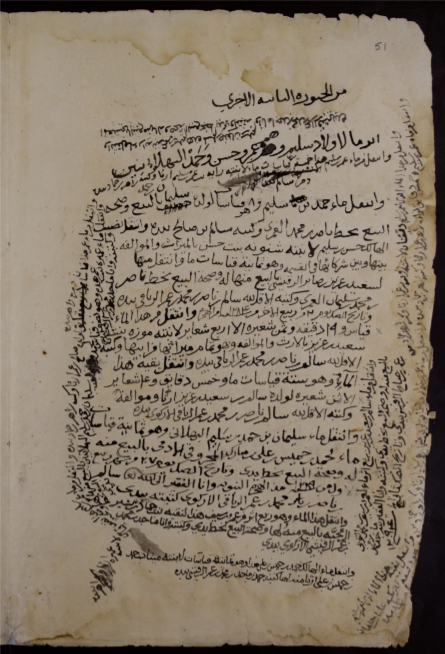

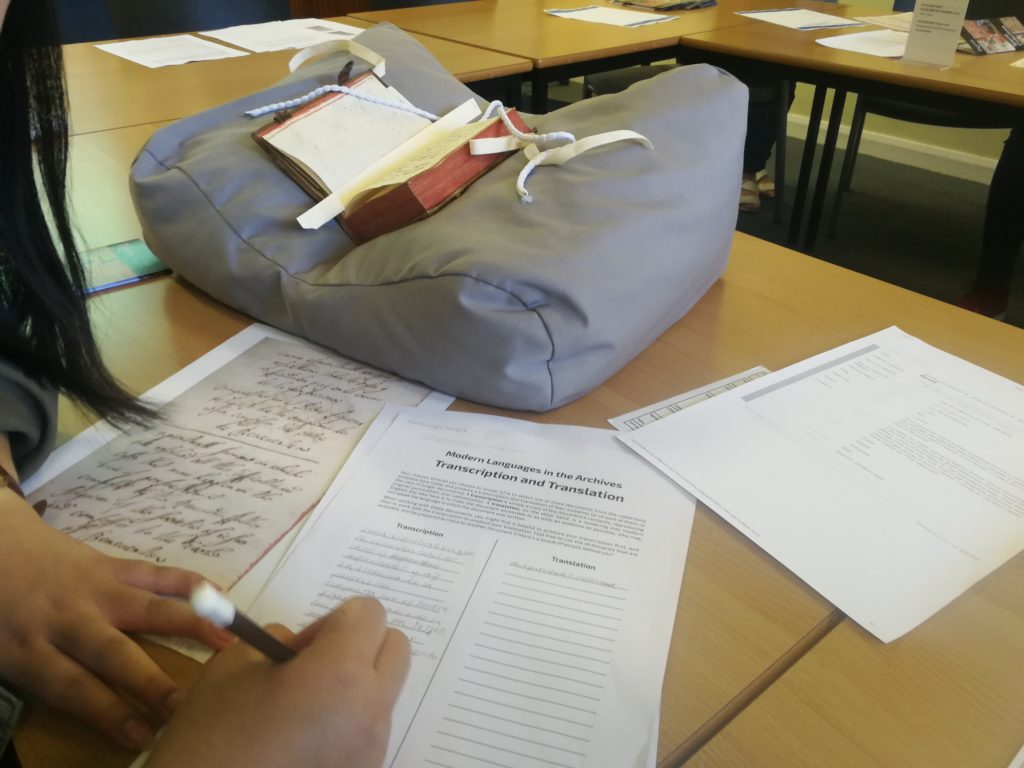

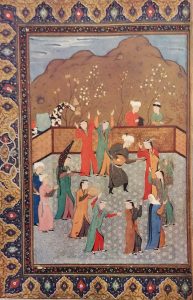

Detail from a 16th century Persian manuscript, from illustrations compiled by Major William Nassau Weech for his ‘History of Persia’ (EUL MS 233)

Iran is bordered by the Caspian Sea to the north, with the Persian Gulf and the Gulf of Oman to the south; Turkey and Iraq lie to to the west, Turkmenistan, Azerbaijan, and Armenia bound its north, while its neighbours to the east are Afghanistan and Pakistan. Iran’s strategic location, as well as its oil resources, have long attracted the interest of both eastern and western powers, and understanding the country’s history is crucial to anyone seeking to grapple with the complexities of Gulf politics, relations between the Middle East, Asia and Europe, and the continuing role played by Islam in the cultural and political development of the region. With tensions between Iran and the USA escalating sharply over the last few days, this is an opportune moment to delve into the materials held in our Middle East archives and Special Collections to see what insights they can offer.

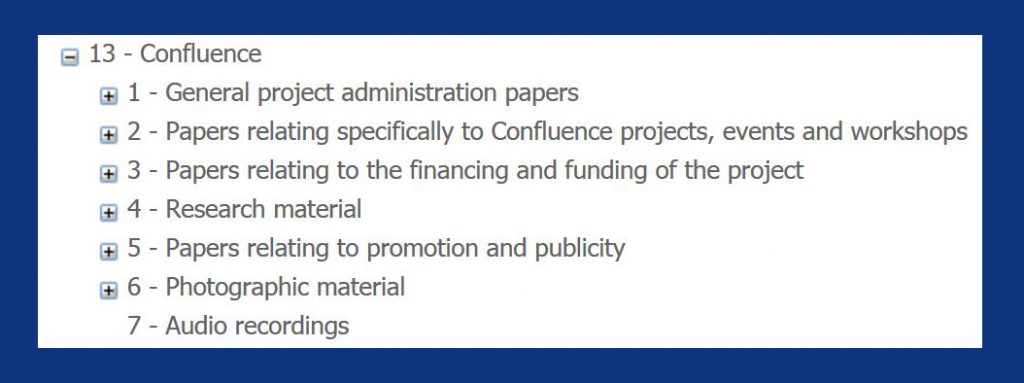

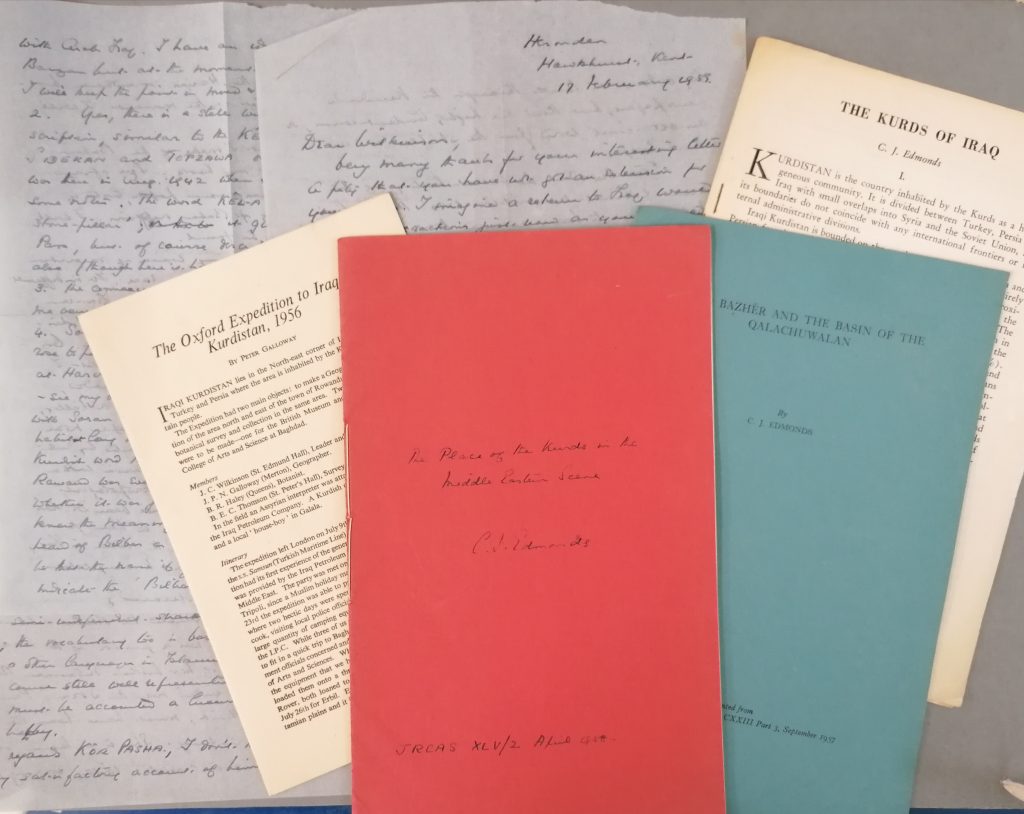

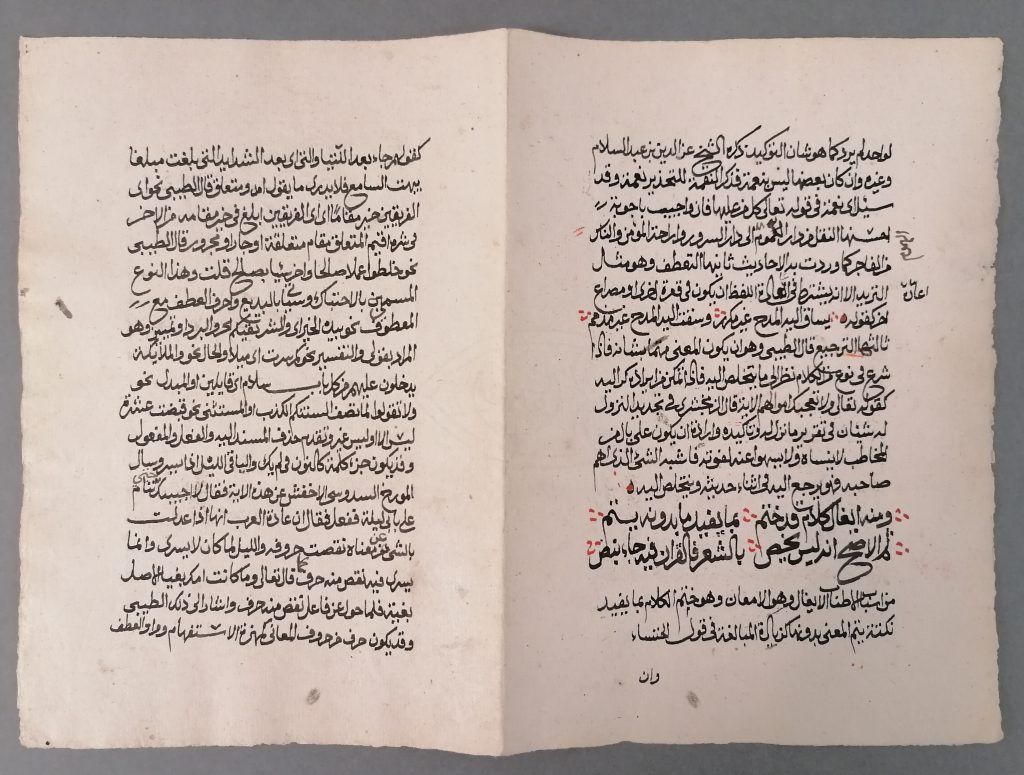

Although there are some offprints and journals within the papers of John Craven Wilkinson (EUL MS 119) relating to the early archaeological and ancient history of the country, most of the archival material held in Exeter University’s Middle East collections dates from the last two centuries – so it is perhaps worth having a quick recap of the modern history of Persia. The Safavid and Zand dynasties that had ruled over Persia since the beginning of the 16th century ended in civil war after the death of Karim Khan in 1779, to be followed by the Qajar dynasty that lasted until 1925. This period was characterised by growing rivalry in the region between Britain in the south – due to Persia’s boundaries with British India (modern Afghanistan and Pakistan) – and Russia in the north. The Tsar’s attempts to expand into the Caucasus region resulted in mass migration of many Muslims into Turkey and Persia, as well as two wars between with Russia and Persia in the early 19th century. These events are vividly described in Laurence Kelly’s excellent book, Diplomacy and Murder in Tehran: Alexander Griboyedov and Imperial Russia’s Mission to the Shah of Persia (Tauris, 2002). In the archive, a great deal of interesting material relating to this period can be found among the research papers of Peter Morris (EUL MS 285), a lecturer at Exeter University who had a special interest in Persian history.

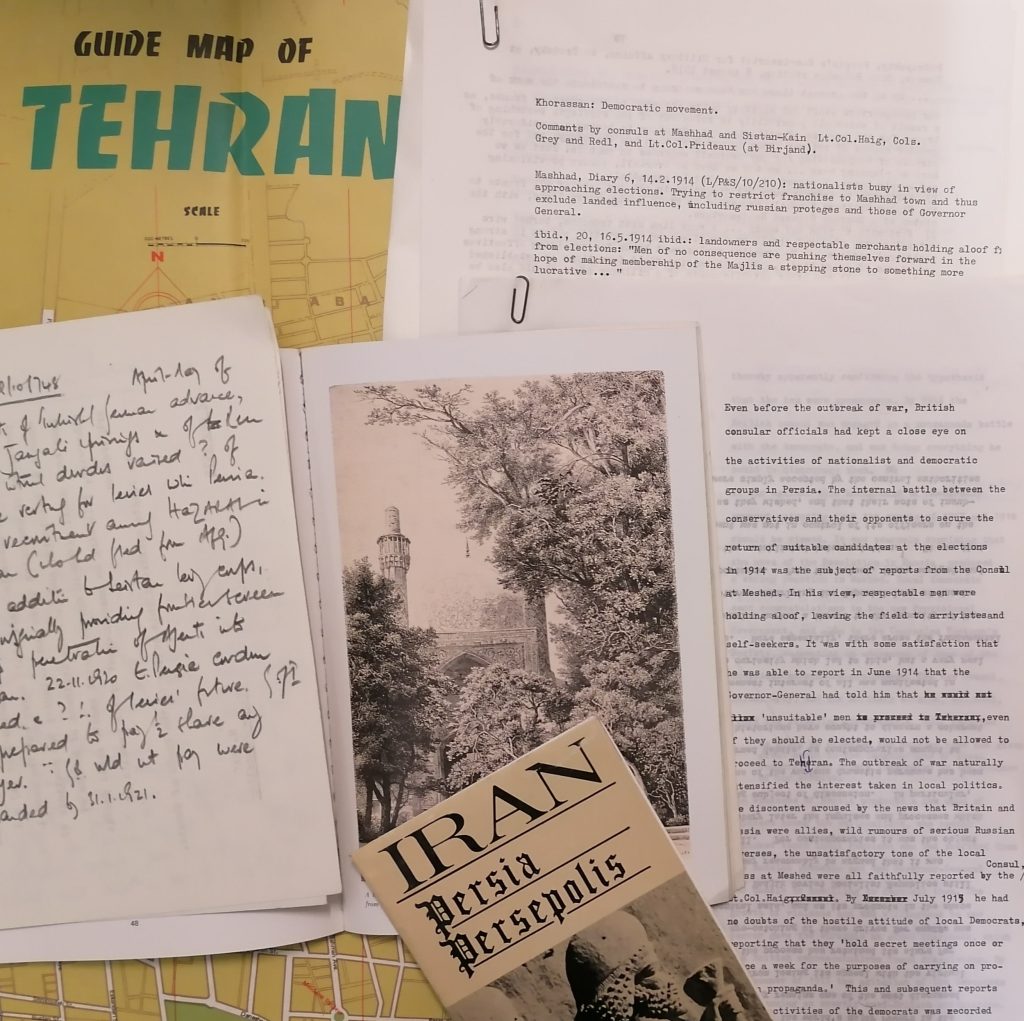

A small selection of material from the Iranian research papers of Peter Morris (EUL MS 285)

Although much of the material is secondary, it includes copies of records from Russian archives and policy documents from the India Office, handwritten and typed notes on ethnic traditions, Persian culture, social attitudes and customs, copies of 18th century correspondence and 19th century typed descriptions of personalities in Persia, financial and agricultural statistics, information relating to the army, trade and administration, postcards of Persian paintings, presscuttings from the 19th and 20th century, as well as guidebooks, maps and personal notebooks. These papers would make an excellent starting point for anyone wishing to undertake research into the history of Iran.

The Twentieth Century: reform and revolution

Iran was ruled at the beginning of the twentieth century by Mozaffar ad-Din Shah Qajar, who had succeeded his father in 1896 and would reign until his death in 1907. He was ill-suited for office, however, and one of his most poorly-judged decisions was to sign away his country’s oil rights in 1901 to William Knox D’Arcy, who subsequently became director of the Anglo-Persian Oil Company (APOC) – later British Petroleum (BP) – and would make a fortune from Iran’s precious natural resources: a cause for resentment by Iranians for most of the century. The Shah’s power was curtailed by the creation of a majles (parliamentary assembly) and democratic constitution, and he died 40 days after this was signed. Concerned over the possible instability of these liberal changes, Russia and Britain signed the Anglo-Russian Convention of 1907, or Convention between the United Kingdom and Russia relating to Persia, Afghanistan, and Tibet, recognising their respective spheres of influence in the north and south of Persia and promising not to interfere either with each other or with Persian sovereignty. This would of course fall apart after the Bolshevik Revolution, and there are various papers on this topic in EUL MS 285/2.

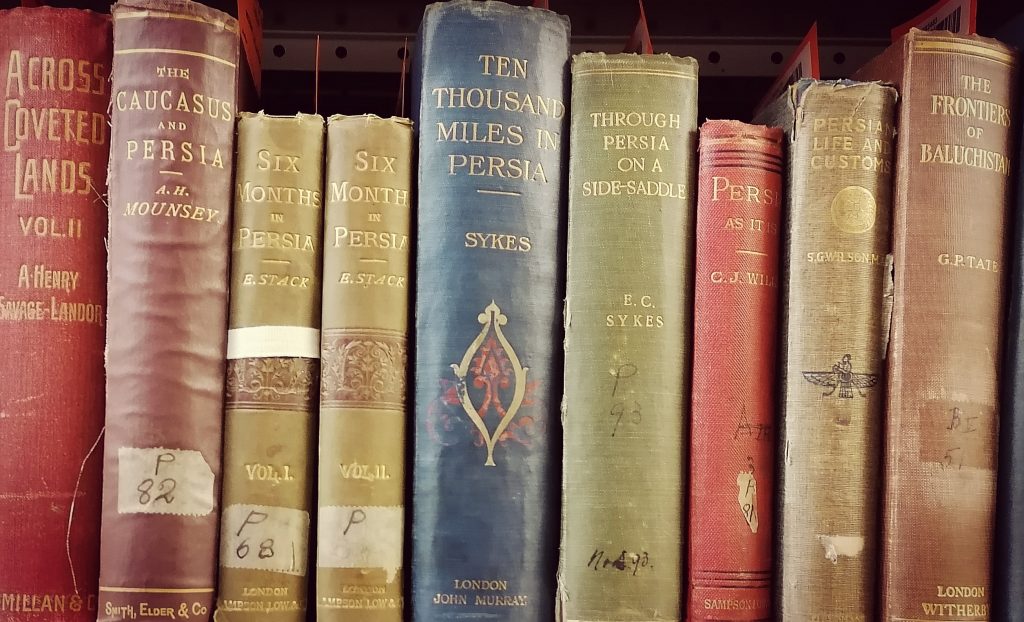

Published works in our rare book collection provide evidence of Britain’s long history of involvement in Iran – in military, missionary, political and mercantile spheres – not only in their printed narratives but also in the material history of the books themselves

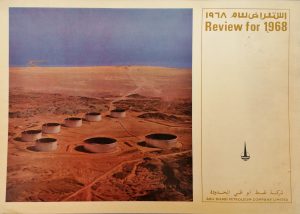

Material relating to the oil industry in Iran can be found among the papers of John Wilkinson (EUL MS 119/2/3/13) as well as Charles Belgrave (EUL MS 148/1/17 and elsewhere). The Shah’s son and successor tried to oppose the constitution and was forced into exile in 1909, to be succeeded by his young son Ahmad Shah, who proved weak and ineffective in dealing with civil unrest and the intrusions of Britain and Russia. He lost his throne in a coup d’etat in 1921, to be replaced by Reza Pahlavi, Commander of the Persian Cossack Brigade, who held the posts of Minister of War (1921-25) and Prime Minister (1923-25) before taking the imperial oath as the first shah of the Pahlavi dynasty. It was Reza Shah who insisted in 1935 that foreign countries used the name ‘Iran’ rather ‘Persia’, although his son would later allow the two to be used interchangeably.

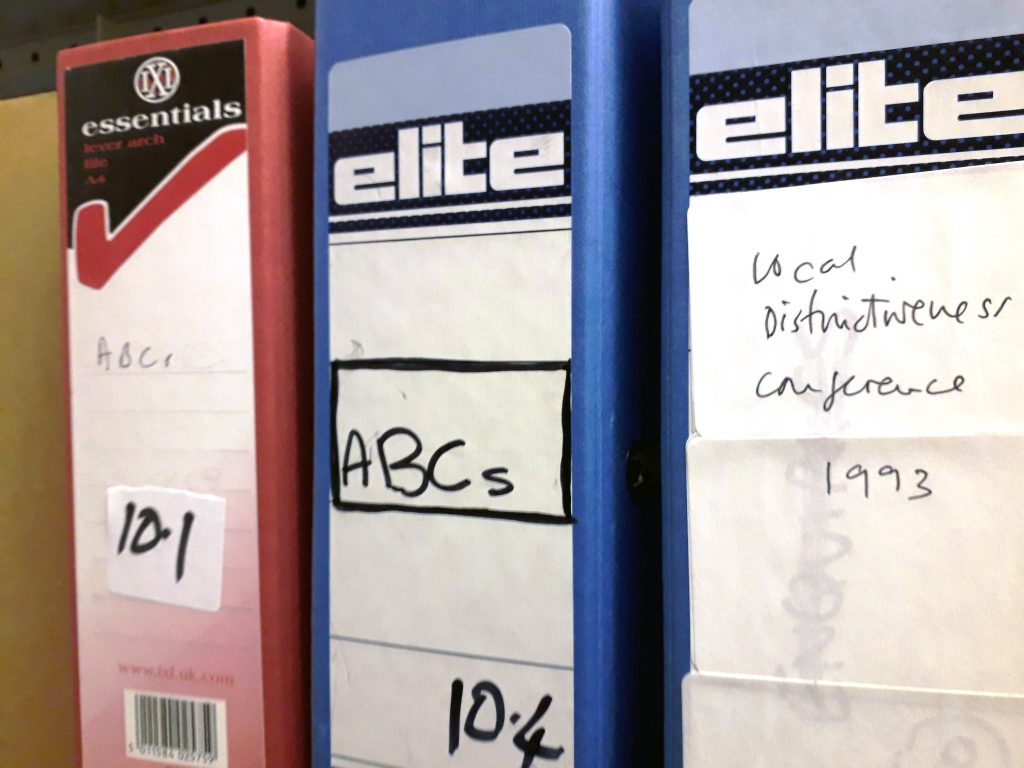

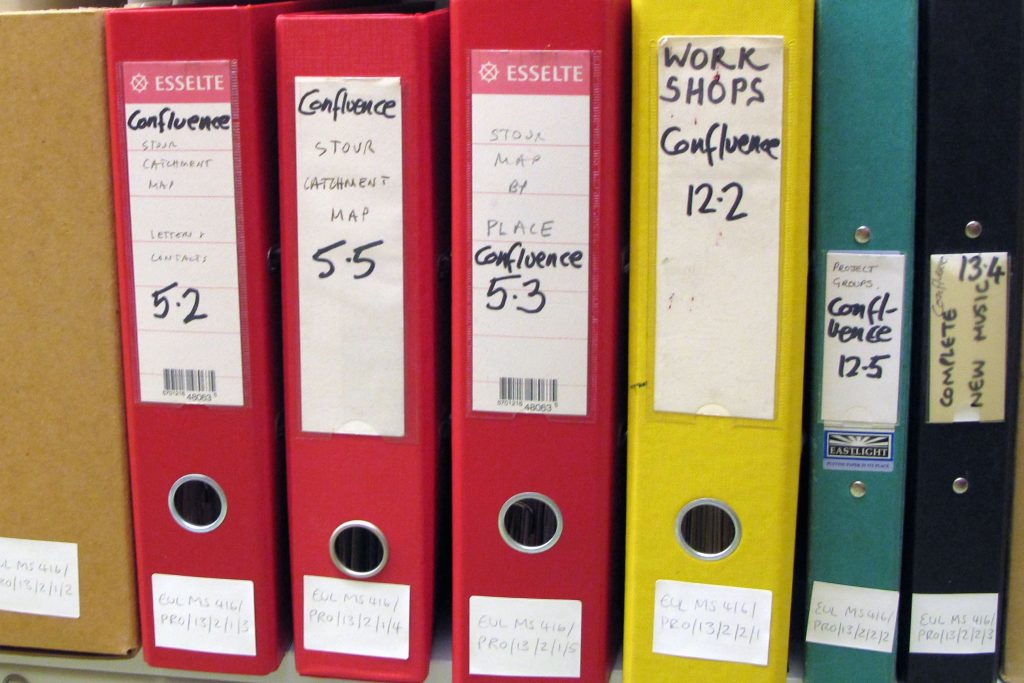

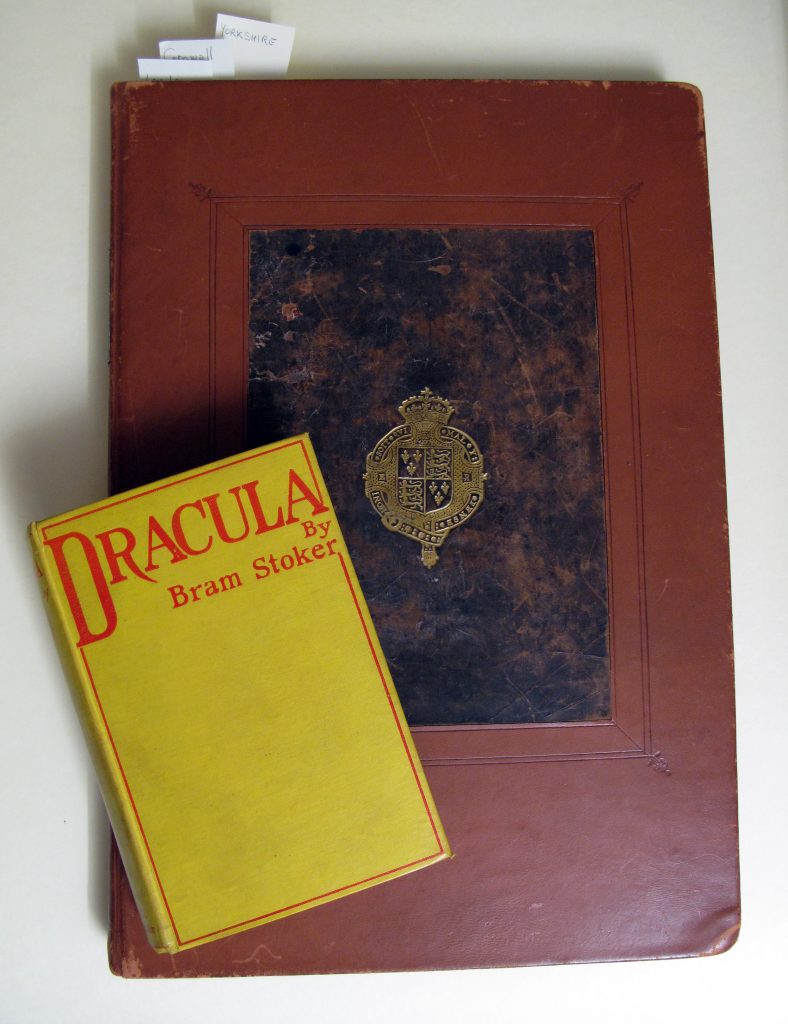

Folder containing a typescript and illustrations for a history of Persia by Major William Nassau Weech (1878-1961), written in 1936 and published as part of his ‘History of the World’ (1944) EUL MS 233

Although Iran underwent far-reaching programme of modernisation under Reza Shah, he was unpopular with many Iranians due to his authoritarian rule and reliance on the military to crush dissent. Inspired by Kemal Ataturk’s reforms in Turkey, he ordered the wearing of modern dress, banned the hijab and established a highly centralised secular administration that broke the hold of Islamic clergy on the educational and legal system. This led to growing opposition from traditional Islamists, clergy, tribal groups, marginalised ethnic minorities such as the Kurds, as well as the younger generation of middle-class intelligentsia who resented his crushing of free speech as well as his association with British imperialism. During the 1930s, however, the Shah developed close relations with Germany, who provided technical and engineering support for the construction of railways, industrial plants and other infrastructure projects. Although Iran remained neutral at the outbreak of WWII, the Allies regarded the Shah with suspicion due to his pro-German policies and refusal to expel the large number of Germans – many of whom were Nazi supporters – living in Iran. An Anglo-Soviet invasion in 1941 brought about the forced abdication of the Shah and his replacement by his son, Crown Prince Mohammad Reza Pahlavi. In keeping with past convention, the Russians occupied the north of the country and the British and Americans the south.

The Kurds in Iran

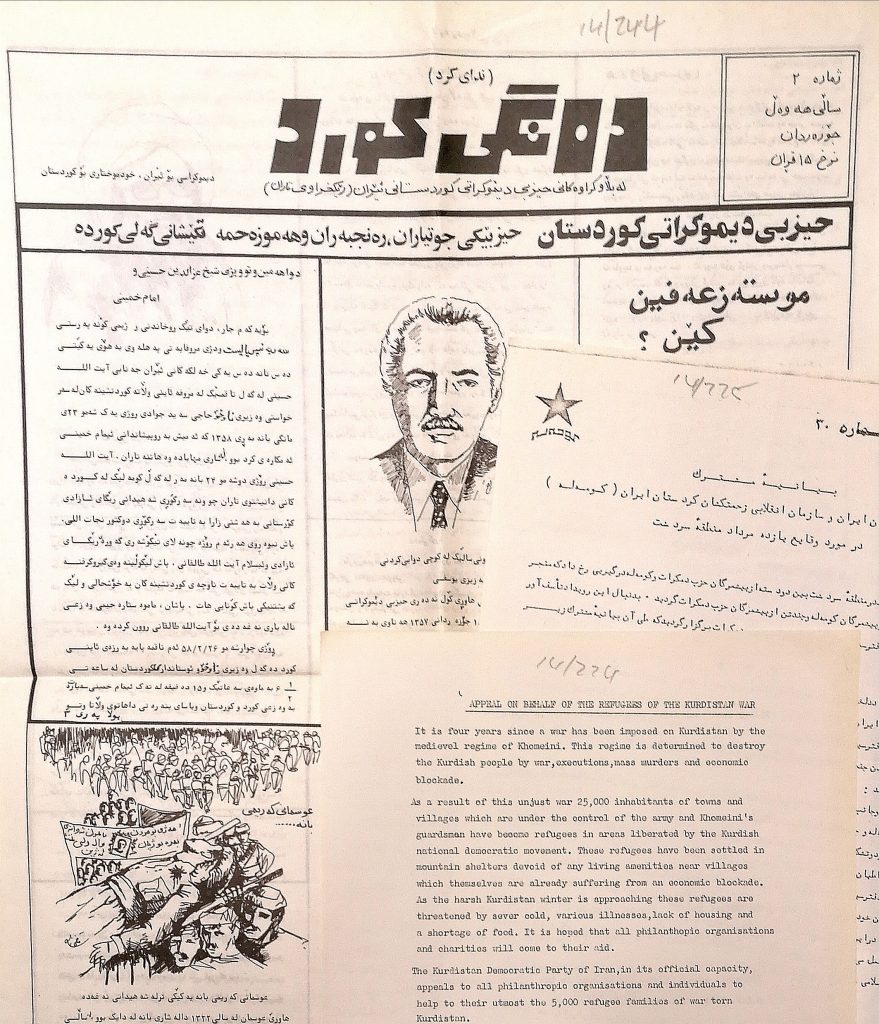

The weakening of the Shah’s power during the period of Allied occupation meant an end to the restrictions on political opposition, including the activities of Iranian Kurds who had long engaged in struggles against the centralised authorities in Tehran. In September 1942, in the town of Mahabad in northwest Iran, Kurdish nationalists formed the Komala-ye Žīān-e Kordestān (Committee of the Life of Kurdistan), whose influence gradually spread throughout the town and surrounding villages, severing all administrative links with the Iranian government in Tehran. They were joined in 1944 by a well-respected local judge Qazi Mohammad, who soon took control of the group. Their aims included autonomy for Iranian and the right to use the Kurdish language in education and administration – and to this end they set up the first Kurdish theatre in Iran, as well as publishing newspapers and periodicals in Kurdish. On 22 January 1946 an independent Kurdish Republic was declared in Mahabad, with its own manifesto, army, girl’s school and a territory that included the nearby Kurdish-speaking towns of Bukan, Piranshahr, Sardasht, Naqadeh and Oshnoviyeh. We have some interesting material relating to Mahabad in the Omar Sheikhmous collection (EUL MS 403), including copies of the periodicals Gir wa Gali Mindalani (Vols.1, Nos. 1-3) and Niştiman (Vol.1, Nos.7-9) and five issues of the newspaper Kurdistan from 1946, which was published by Qazi Mohammad’s Democratic Party of Iranian Kurdistan (Hîzbî Dêmukratî Kurdistanî Êran). The latter two titles are in Sorani Kurdish. The Republic received the promise of military and financial backing from Soviet forces, as well as armed support from Iraqi Kurdish leader Mostafa Barzani (1903-79), who brought with him several thousands Kurdish fighters and their families from over the border.

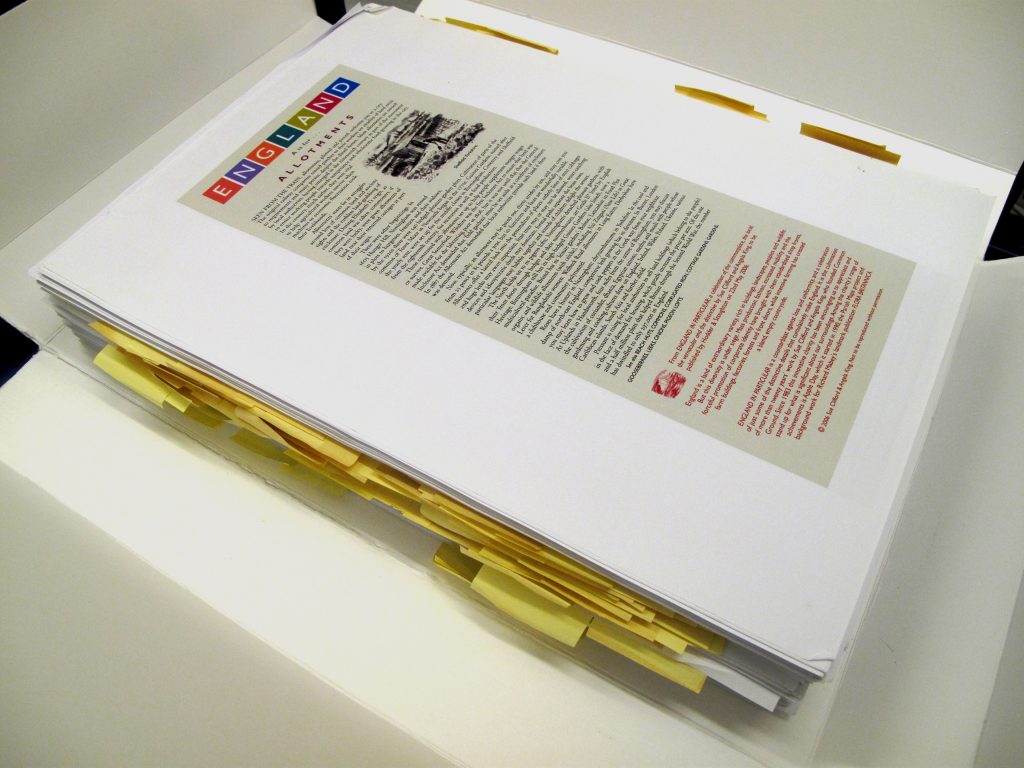

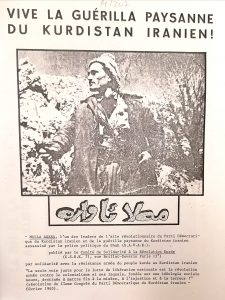

Some of the large number of documents – in Persian, Kurdish, English, Swedish, German and French – in the Omar Sheikhmous archive (EUL MS 403) documenting the history and political struggles of the Kurds of Iran

Mohammad had, unfortunately, overestimated the support of the Russians as much as he had underestimated the wiliness of the Iranian prime minister Ahmad Qavam, who played the various parties off against one another, and offered the Soviet authorities generous oil concessions in exchange for the withdrawal of their forces from Iran. In December 1946 the Iranian army entered Mahabad, ending the short-lived Kurdish republic. Despite the peaceful reconquest of the town, the leaders were shown no mercy: on 23 March 1947, Qazi Mohammad, his brother Sadr Qazi and cousin Sayf Qadr were hanged in the town centre. An undated French leaflet among the Sheikhmous papers is illustrated with a photograph of their execution.

The Latter Years of the Shah’s Reign

One of the most significant crises in Iran during the Cold War occurred in 1952 when Prime Minister Mohammed Mosaddeq – a senior figure in the Communist Tudeh party – sought to nationalize the British-owned oil industry and return its revenues to Iran. This resulted in an economic blockade, an attempted coup, the temporary exile of the Shah, and a complex power struggle between Mosaddeq, the Shah, the military, Islamic clergy and crowds of rival demonstrators who were paid by the American government to instigate trouble on the streets. Mosaddeq was eventually removed in a CIA and MI6 backed coup in 1953, the Iranian oil industry was restored to British ownership, and from then on the Shah pursued a liberal, pro-western policy – branded the ‘White Revolution’ in 1963 – that was nonetheless autocratic, authoritarian and deeply corrupt, relying on rigged referendums and the brutal methods of the SAVAK security forces. It was, however, the Shah’s hostility to Islam that particularly drew the criticism of an outspoken Muslim cleric, the Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini who was based in the holy city of Qom. Born in 1902, the charismatic and scholarly Khomeini was widely revered, and rather than risk a backlash by having him executed, the Shah had the 62-year old cleric arrested and deported in 1964. He would spend the next fifteen years in exile in Turkey, Iraq and France.

The Shah’s unpopularity continued to grow during the 1970s, partly due to the way in which the oil boom of that decade seemed to the Iranian people to made the Pahlavi family and their friends immensely rich while leaving much of the country in poverty. British interests in the Gulf region underwent a major change with the withdrawal of British forces from the Gulf in 1971, and Sir William Luce met the Shah several times during the period of his shuttle diplomacy between 1970 and 1971. (Records of their conversations can be found amongst Luce’s papers, e.g. EUL MS 146/1/3/1, 1/3/7 and 1/3/8.) The Shah also met with Glencairn Balfour-Paul, who was based in Bahrain during the late 1960s as deputy political resident of the Persian Gulf, followed by another post as British ambassador to Iraq (1969-72) – there is an informal photograph of the Shah and his wife amongst Balfour-Paul’s papers (EUL MS 370/6/34.)

On the domestic front, however, the Shah proved unable to control the waves of protest that shook the country during the late 1970s, and eventually fled Iran in January 1979. The papers of Sir John and Lady Richmond contain a file of presscuttings covering these events (EUL MS 115/19/13). The British, seeing the direction in which events were heading, had already dropped their support for the Shah and took the further step of refusing him asylum. He died in Egypt the following year.

Ayatollah Khomeini returned to Iran to a tumultuous welcome on 1 February 1979. One of the Shah’s final acts had been to appoint Shapour Bakhtiar as Prime Minister. Khomeini refused to recognise his authority, and after ten days of chaos and fighting Bakhtiar’s weak and isolated administration collapsed, to be replaced by Khomeini’s Islamic Republic of Iran. Over the next ten years – until his death on 3 June 1989 – Khomeini served as Supreme Leader of Iran, a decade that saw the revolution consolidated into an Islamic theocracy as well as a long and bloody war with Iraq.

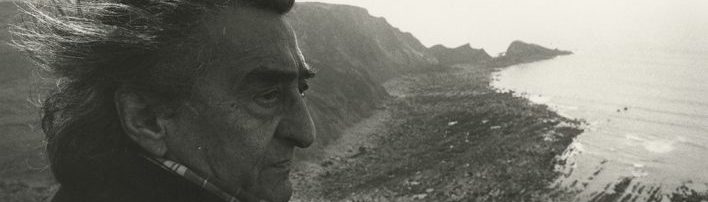

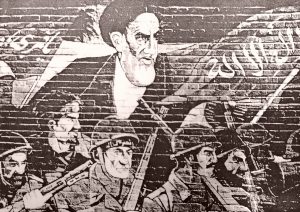

Detail of a mural in Tehran showing the Ayatollah Khomeini during the war with Iraq. From the papers of Jonathan Crusoe (EUL MS 143)

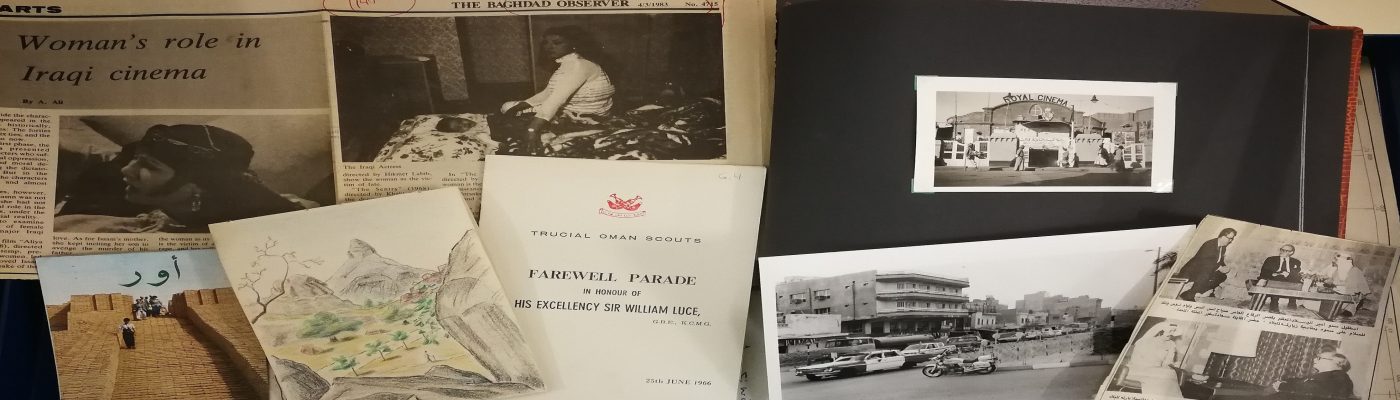

This was chronicled in detail by Jonathan Crusoe, and among his papers are several folders on the ‘First Gulf War’ (1980-88) between Iran and Iraq as well as other files relating to relations between the two countries (EUL MS 43/10/2/1-6). Iran’s seizure of the Tunb Islands in the Straits of Hormuz is discussed in several articles in the Baghdad Observer, which would make an interesting comparison with Sir William Luce’s accounts of the same event amongst his papers.

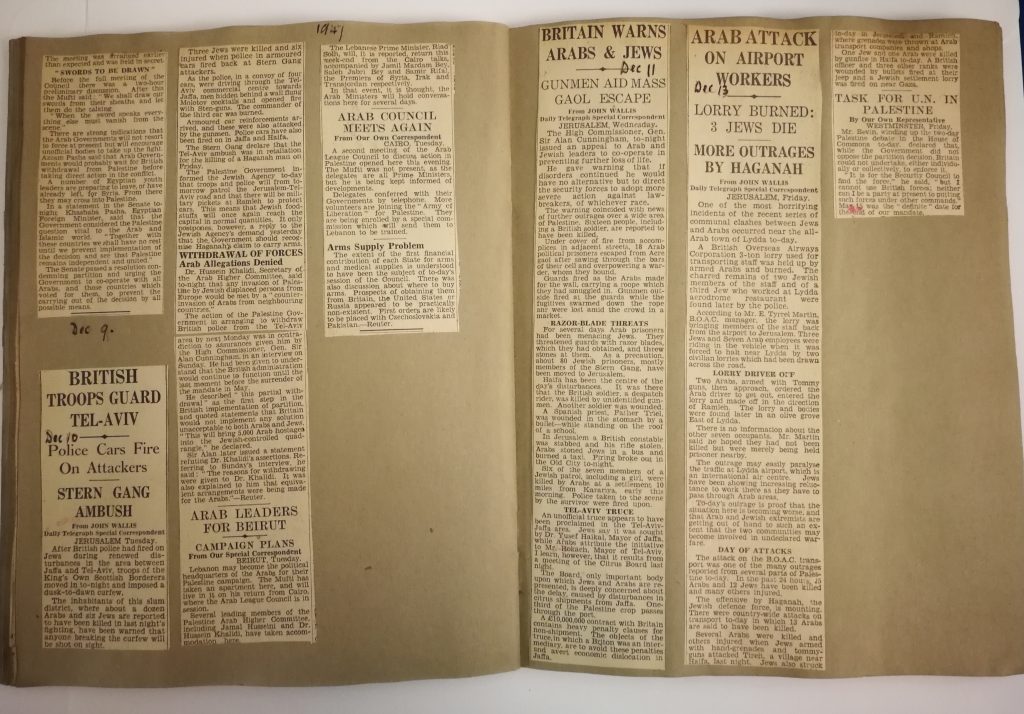

Some of the presscuttings and other documents assembled by Jonathan Crusoe on the subject of the First Gulf War between Iran and Iraq (1980-88), many of which offer insights into how Iran’s history, culture and political intentions were perceived by Iraqi

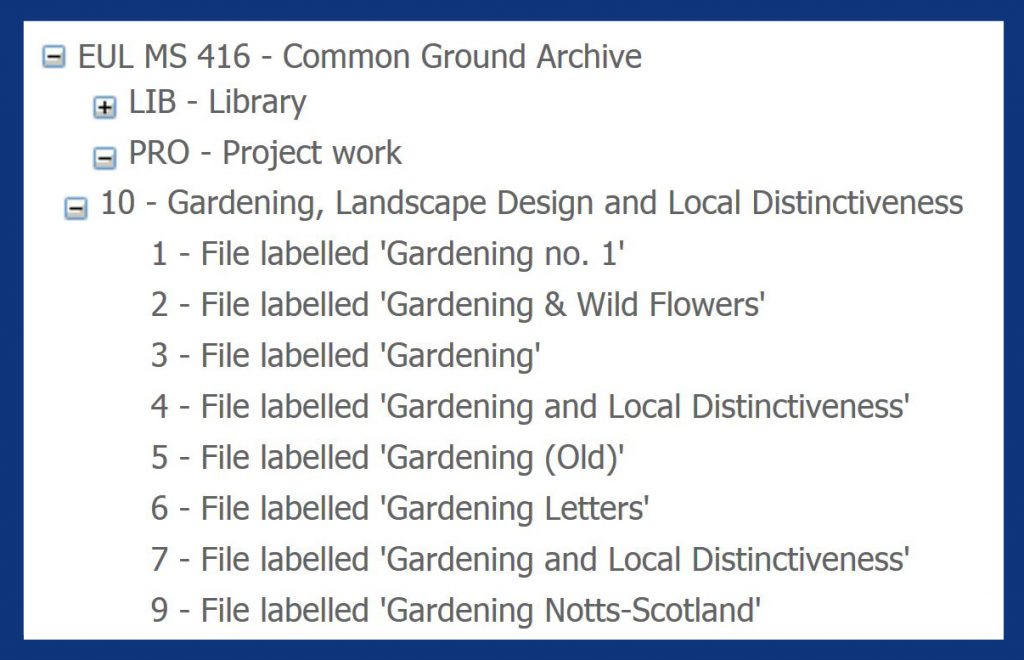

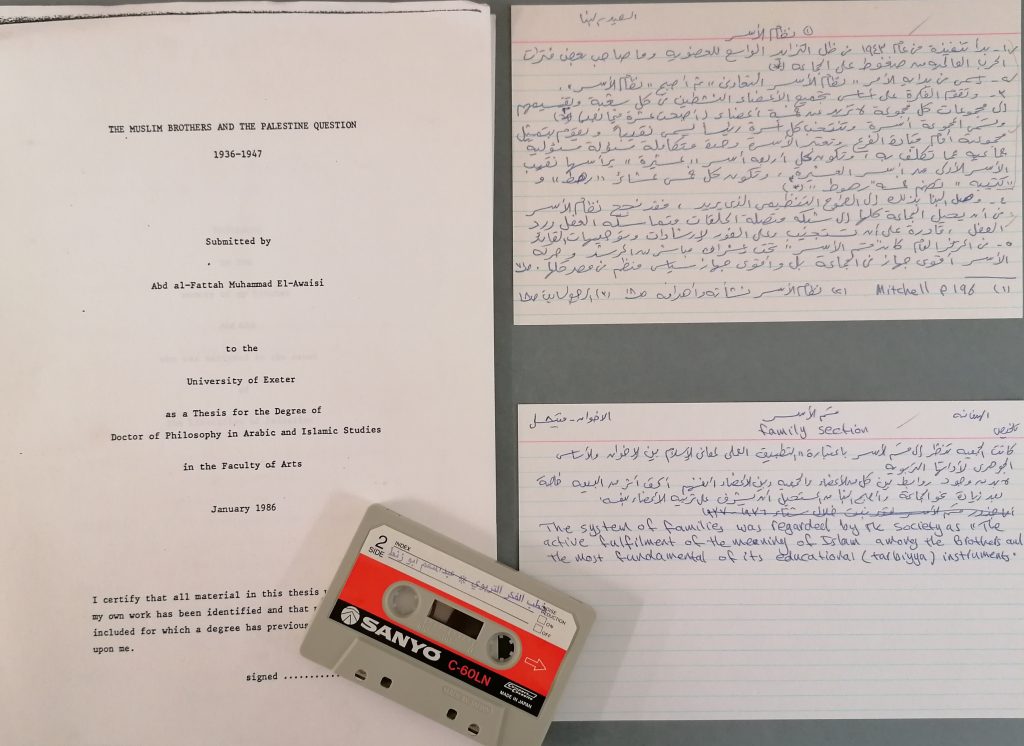

Various scholarly assessments of Khomeini’s rule and the Islamic revolution in Iran can be found among the academic papers of Nazih Ayubi (e.g. EUL MS 129/1/1/9, 129/1/2/5, 129/2/1, 3 and 30.) It should also be noted that there is an audio recording of a conference on Iran held in the El-Awaisi collection (EUL MS 284). Following Khomeini’s death in 1989, Ali Khamenei was appointed the next Supreme Leader and – thirty years on – remains in post. Although the Supreme Leader possesses ultimate religious and political authority in Iran and is responsible for appointing the Prime Minister and all other military and judicial leaders, it has been claimed that he functions as more of a figurehead for other powerful forces within the conservative establishment. There is no denying the significant differences between Khamanei and his predecessor in terms of religious education, cultural tastes and popular standing, and he remains a divisive figure for many in Iran, which has seen widespread anti-government demonstrations over the last two or three years.

The relationship between the Supreme Leader and the government is however, a complex one, as would be expected in a theocratic state. The power structure in Iran includes an array of different elements that includes the Supreme Leader, the President, Parliament and Judiciary, the Council of Guardians – who monitor parliamentary decisions for compatibility with Islamic law, the Assembly of Experts – who elect the Supreme Leader – the Ministry of Intelligence and Security (MOIS), and the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, which was founded by Khomeini in 1979 to safeguard the principles of the revolution, and is fiercely independent from the regular army.

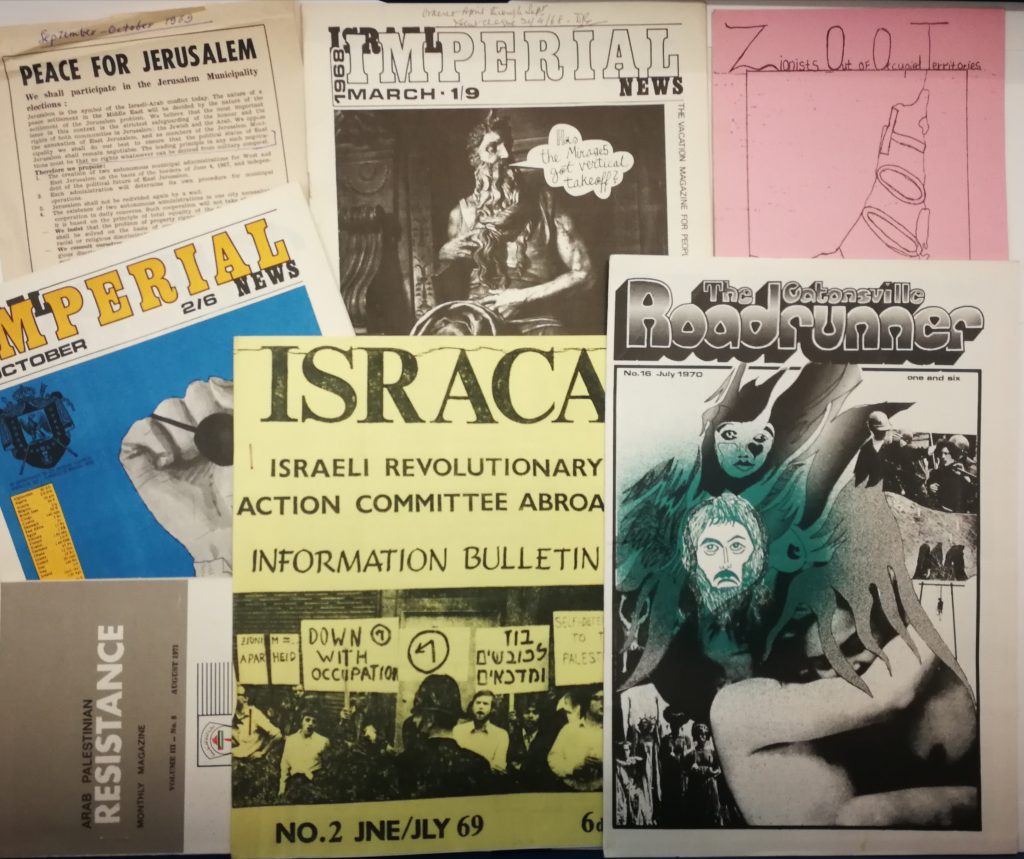

Those who wish to understand Iran today will need to spend a substantial amount of time working out the dynamics between these different centres of power, studying the personalities and abilities of the key figures, and learning how they operate both within Iran and as part of the wider political, religious and cultural context of the Gulf region – including its involvement in the affairs of Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Palestine, Yemen, Bahrain and elsewhere. Perhaps more than most other countries in the Middle East, commentary on Iran has suffered badly from a vast chasm between how outsiders view the country and how it is seen from within. Anyone seeking to bridge this chasm must begin by acquiring a solid grasp not only of Persia’s long history but also of the diverse and conflicting movements that are currently helping to shape contemporary Iran. The archival materials held in Special Collections provide unique insights into this subject, and can of course be complemented by drawing on the rich resources held alongside in AWDU (the Arabic World Documentation Unit), which include a wealth of ephemera, economic reports, statistical records, leaflets and presscuttings, Iran in the Persian Gulf 1820-1966 (Slough: Archive Editions, 2000) – a six-volume collection of facsimile government papers – plus official material relating to the oil industry, trade and banking.

For any questions, please contact the Middle East Archivist.

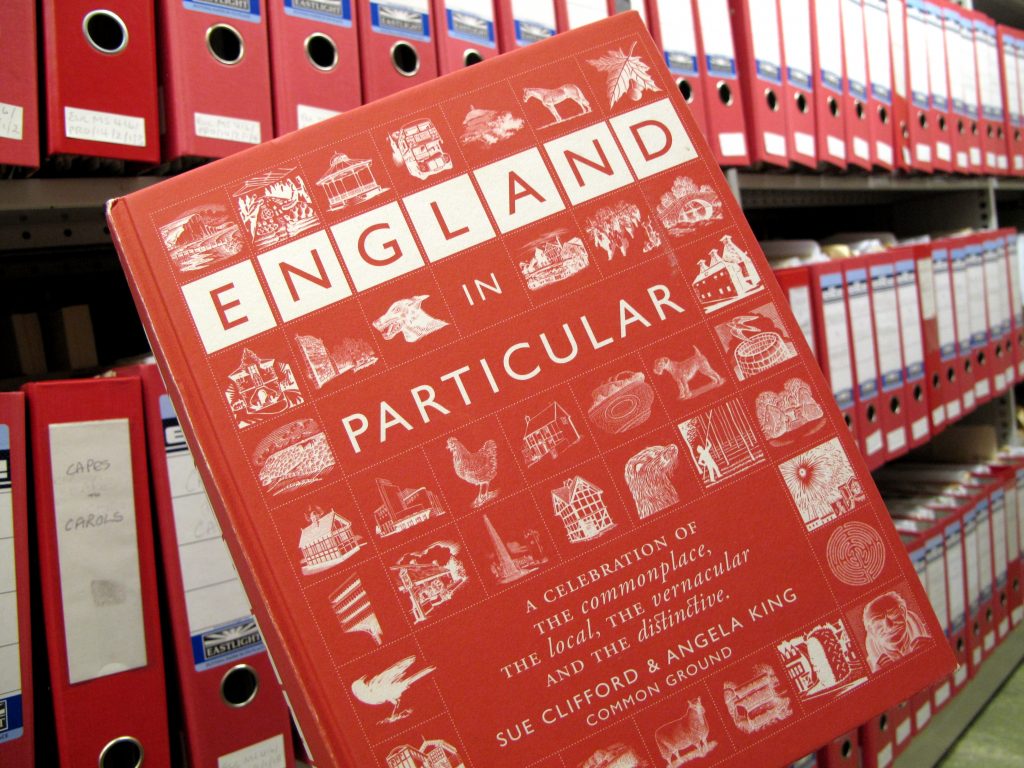

A few of the titles in the rare book section of Special Collections relating to the history of Iran and its neighbours. Many of these are illustrated with photographs and engravings, as well as maps, from the 19th and early 20th centuries.