Earlier this year, Special Collections launched its first remote internship for University of Exeter students. Unable to run our usual in-person work experience programme, and knowing that another lockdown at the start of 2021 was highly likely, we were pleased to offer an opportunity for students to gain valuable archive experience whilst working from home.

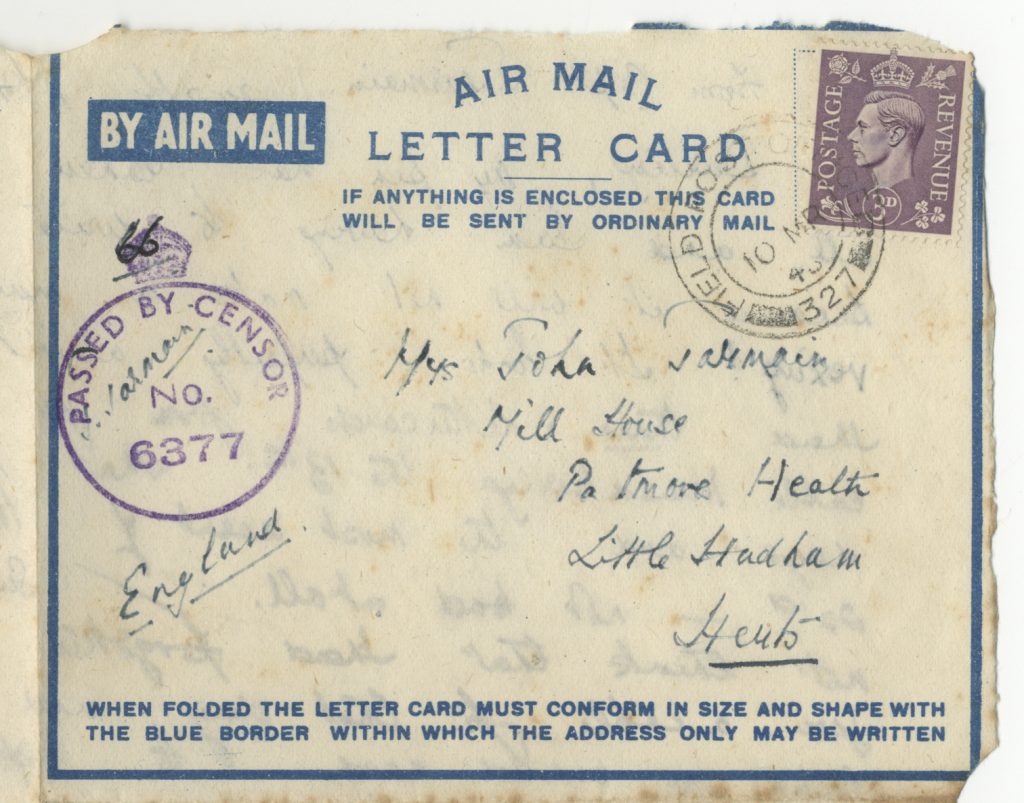

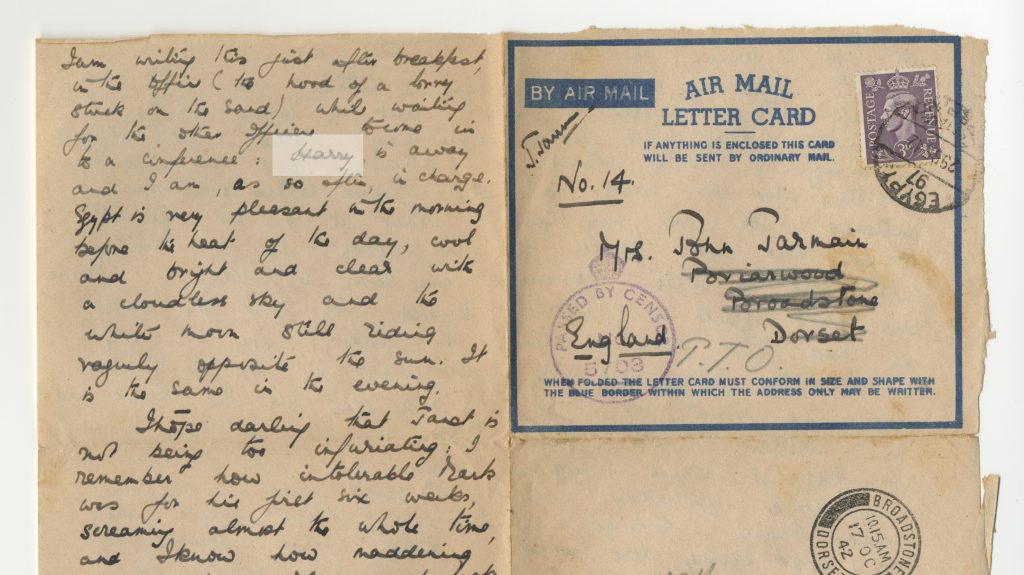

The collection we chose for this remote internship was the Letters of John Jarmain (EUL MS 413). William John Fletcher Jarmain (1911-1944) was a novelist and poet. He served throughout the Second World War as a gunnery officer with the 51st Highland Division during their campaigns in North Africa and Sicily. He took part in the D-Day landing and was killed in action on 26 June 1944. The collection comprises 120 manuscript letters that he sent home to his wife Beryl between June 1942 and November 1943.

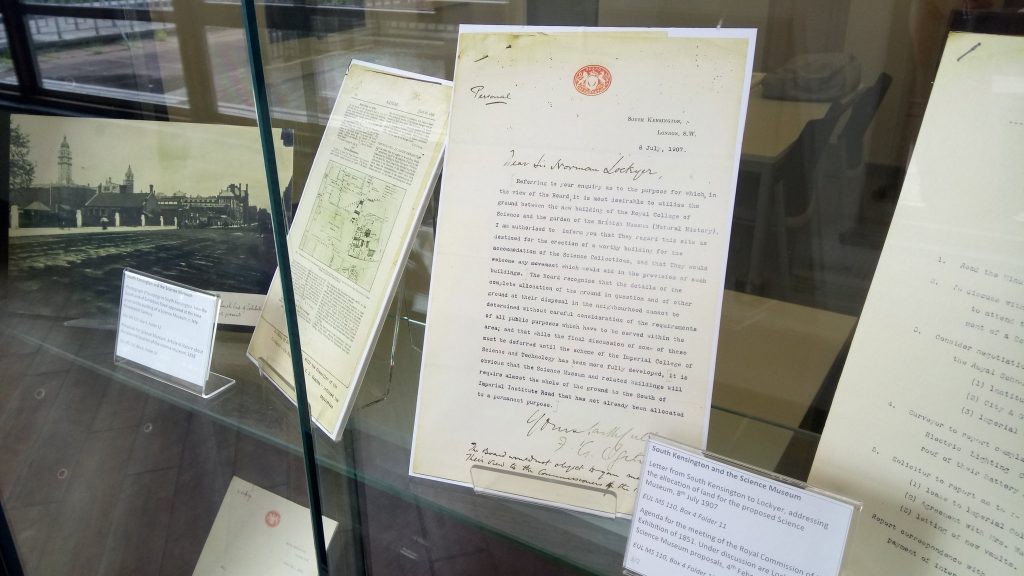

Digitised images of all of the letters are available to view online through our Digital Collections website, making them ideal for our interns to access and transcribe from home. Once proofread, the transcripts produced by the interns on this project will be uploaded to the website to sit alongside the digitised letters, enabling letters of interest to be more easily identified, accessed and understood.

We would like to take this moment to thank our interns, Beth Howell and Ruby, for their hard work, diligence and enthusiasm for this project. Through a combined effort, they recently completed the transcription of all 120 letters – an amazing achievement! Below you can read their reflections on the project.

Reflections by Beth Howell

Transcribing the letters of a person is always a very involved experience, and working on John Jarmain’s war-time correspondence has proven to be no exception. However, perhaps because Jarmain was so engaged with the process of writing, (often demonstrating himself to be an almost obsessive editor of his own poetry), he always seems to write with a real sense of how his words might be read and interpreted in the future, making his letters a real privilege to read. Though most of his correspondence is addressed to his wife, Beryl, he often appears to imagine a reader beyond her, documenting the world around him with a real sense of capturing the present moment. His letters are therefore not only interesting because of what they reveal about his poetic practice, but also the landscapes he found himself in, the relationships he fostered, and his hopes and anxieties for a future after the war.

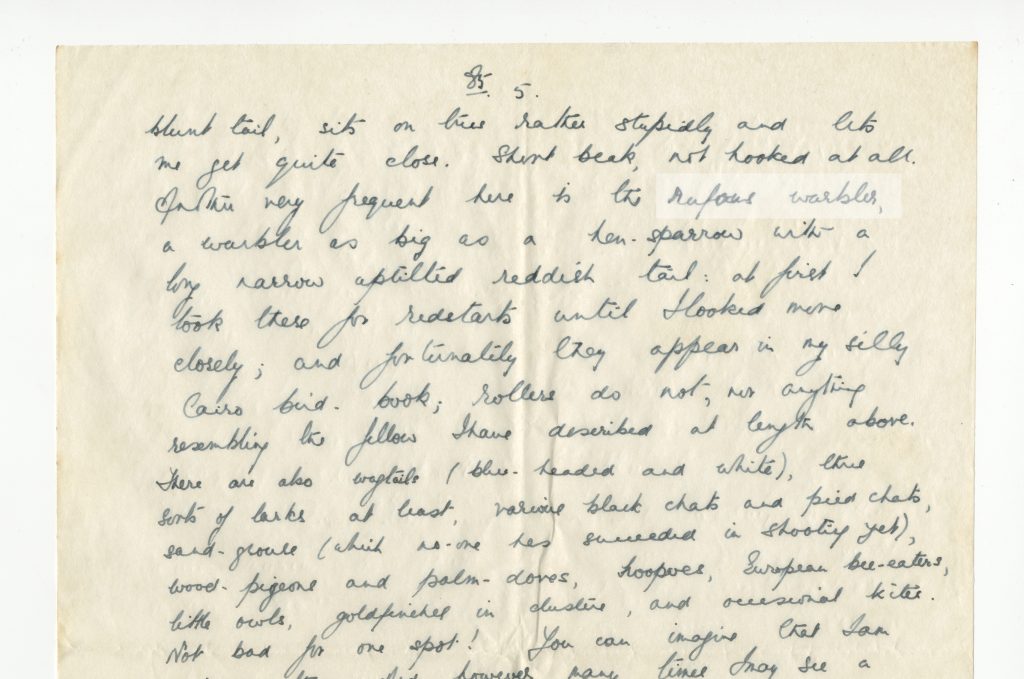

My favourite element of Jarmain’s writing, though, was probably the way in which he balanced larger concerns with little details. His ability to find joy in the spaces around him, even though the vision of those landscapes necessarily meant his separation from home (and, of course, were imbued with the ever-present anxieties of potential battles), is really heartening and beautiful to read. He loved birds, and many of his letters are preoccupied with identifying species from a little bird book he bought and carried around with him. (Though I have to say that deciphering rare specimens from his sometimes quite hastily-scribbled writing presented a few challenges- I had certainly never heard of a rufous warbler before!)

EUL MS 413/1/85 – Letter dated 30 April 1943, in which Jarmain writes about birds, including the rufous warbler (highlighted)

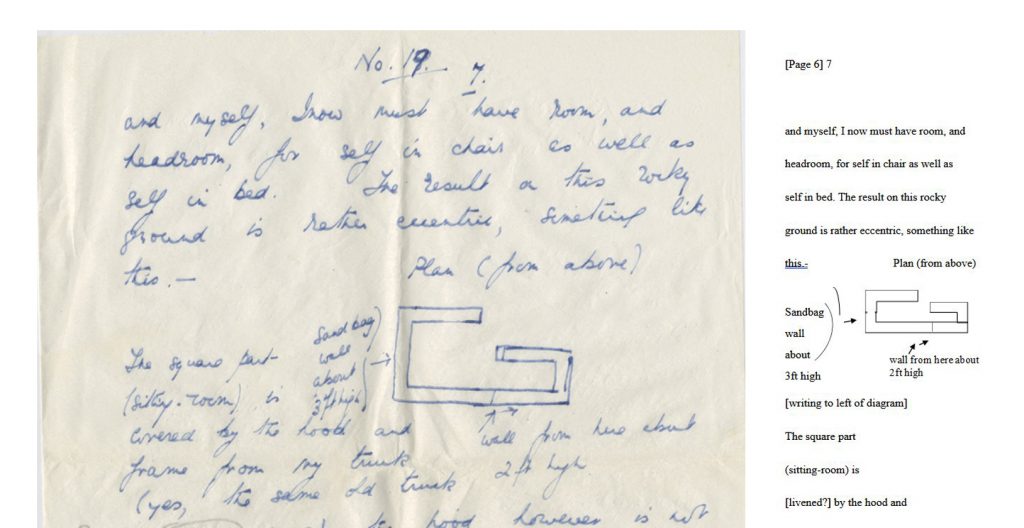

I also admired his confidence in informing his wife that he had fallen in (platonic) love with various women during his time in service- including Yone May, the subject of one of his poems. Jarmain presents a tangible picture of contemporary technologies (or quite the opposite), which affect his writing in a very material way- he finds himself scribbling in pencil, writing by candlelight in the wee hours, hastily penning an aerogram when he knows the post is leaving soon. He laments his ability to construct suitable diagrams of views and barracks, continues to marvel at unexpectedly quick postal deliveries, and to agonise when the opposite proves to be the case. His letters are a fascinating and absorbing insight into his life away- checked only by the knowledge that his observations would be tragically cut short. Jarmain died, killed by a fragment of mortar shell, on Saturday 26th June, 1944.

Reflections by Ruby

It hardly seems right to call this internship “work”. Work refers to something laborious, something that has to be done, but I found transcribing John Jarmain’s letters delightful. It saddens me that the World War II poets don’t receive the same attention as the World War I poets. Jarmain, though brilliant and sensitive, is far from a household name and does not even have a poetry collection currently in print. This is what makes me so genuinely honoured to have been involved in this project, typing up his letters, so that we can start to make Jarmain’s literature more accessible for more people. I hope that, going forward, people will read these letters and be touched in the same way that I was.

This internship has shown me that there is a big difference between reading for pleasure and reading to transcribe. Transcribing Jarmain’s letters has forced me to read them carefully, sensitively and attentively. I have had to pay attention to punctuation, names and form which I might not otherwise have paid much attention to. When I’ve read letters from authors in the past, I don’t tend to focus on people who are off-handedly mentioned (cousins, distant friends, colleagues etc.), and only really focus on those they are closest to. However, when writing up these letters I had to pay attention to every name — zooming in to make sure that I got every surname right — and, in doing so, I noticed certain people who popped up time and time again (his friend, Harry, for example). Jarmain’s handwriting also means that it’s easy to mistake a semicolon for an exclamation point. At first glance, his semicolons can look like exclamation points, but when you look more closely, they’re usually not. If I were reading these letters at a glance, I would think that he was just heavy-handed with exclamation points, but this project showed me that he is not, and that he actually uses exclamation points quite sparingly. Over the course of the internship, I became more familiar with Jarmain’s writing style and more attentive to quirks in his handwriting. For example, when writing “a”, he tends to attach it to the word in front (i.e. if he says “a ship”, he will write “aship”). This led to some tenuous guessing at the start of the project; however, I was familiar with this by the end, and found transcribing his letters much easier.

The internship showed me how important it is to read letters attentively and slowly — to savour them and their images and their kindnesses. This is what Jarmain’s wife, Beryl, would have done, and so we perhaps get closer to the experience of these letters when we read in this way. Having to read Jarmain slowly was probably my favourite part about and, as a consequence of having done this, I feel like I know him better than I otherwise would have done.

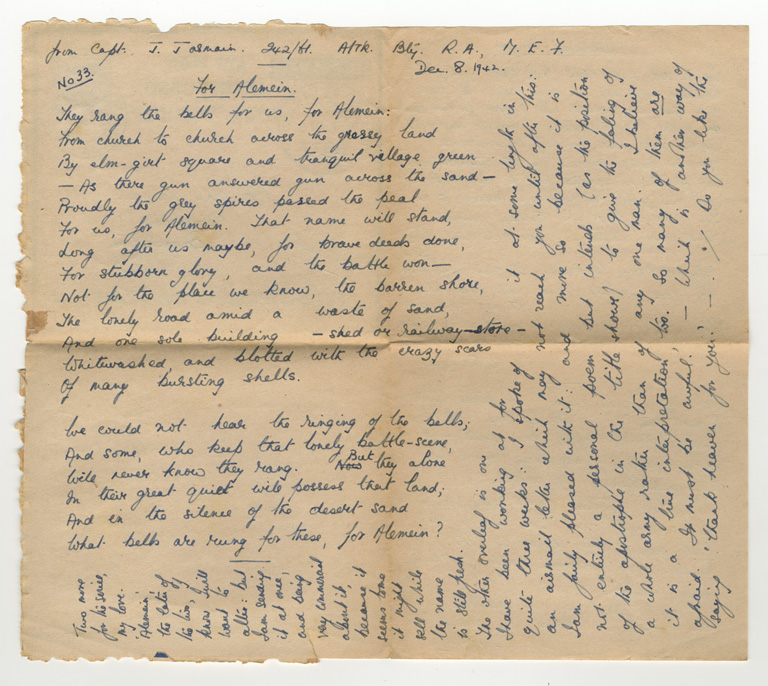

One particularly striking part of Jarmain’s letters is just how little he refers to the actual events of war. He hardly talks about what his troops are doing, and any danger they might be in. Rather, he documents domestic experiences — for example, how he spent his time on leave, or how he goes swimming in the morning before starting work, or a joke told by one of the men. Jarmain separates himself from his identity as the “soldier” and presents himself as a real man, the same husband to whom Beryl waved goodbye. Though this is humbling to see, it also points to the separation between war and home which he documents in his poem ‘El Alemein’. The separation between Jarmain as husband and soldier in these letters makes the dramatic irony of his death all the more upsetting. Reading the letters, I knew that he would never come home and safely settle back into domestic life. In one of his last aerograms (EUL MS 413/1/153), he writes of the Christmas presents he plans to give them, clinging to the possibility that the war will end soon and he will be home with Beryl and Janet-Susan. When the letters abruptly stop, there is no warning and, since he was so secretive about his life as a soldier when writing to Beryl, it seems strangely incongruous that he could have been killed in war.

Possibly my favourite parts to transcribe were his descriptions of nature — and, in particular, his descriptions of Italy in his final aerogram (EUL MS 413/1/154): “Away to the right, tier upon tier lit in streaks of sun and shade and clotted with white clustering towns, were the hills of Italy across the strait. In England you cannot imagine such beauty, such a scene”. You can feel the wonder in his voice here and the sheer extent of the view he relays. These nature descriptions are occasionally shown in his poems, but only fleetingly, and I enjoyed reading this different writing style from him. It is also so illuminating to see the poems embedded within these letters because the poems will often refer to images he’s already described for Beryl. For example, in letter one (EUL MS 413/1/1), he writes that he “was struck suddenly by willows, English willows, how they stand in rows like thick-handled powder-puffs, grey-green in the evening”. Then, in a poem in letter two (EUL MS 413/1/2), he writes that the train “Passed willows greyly bunching to the moon”. In this, we can see his poems as snapshots of real, personal experience. Indeed, the fact that they are embedded within letters shows just how intimate and personal they are, which can and should encourage us to read them contextually in new ways.

Ruby has very kindly recorded herself reading John Jarmain’s first letter (EUL MS 413/1/1). Click on the play button below to listen to the recording.