In July 2019, a week-long summer residential programme for Year 12 students took place at the University of Exeter. As part of the Modern Languages strand of the programme, PhD student Edward Mills led a translation workshop using French- and Spanish-language material from our Special Collections. We were delighted to be involved in this workshop and would like to thank the students and Edward for their ingenuity and enthusiasm in working with the material.

In this guest blog post, Edward Mills shares some of the students’ translations and explores how modern language skills can be used to unlock archives and bring history to life…

What makes Special Collections ‘special’? There are many ways to answer this question, and as the University of Manchester notes in their introduction to their own collections, ‘there is no simple, catch-all definition’ that neatly encompasses all of the material that we keep here in the Old Library. One common thread that does emerge from our colleagues’ reflections, though, is that of uniqueness: many of the items in Special Collections, whether in Manchester and in Exeter, are one-of-a-kind items. This may be because of the way in which they were produced, as is the case with the medieval manuscripts in the Syon Abbey collection, or owing to how they were used later, as we can see in Jack Clemo’s unique treatment of his Boots annual diaries.

These unique items often require the reader to have specialist skills in order to be able to interpret them. This might entail training in palaeography, or else an understanding of how patterns of book-binding changed over time; equally important, however, are language skills. Many of the documents in Special Collections here at Exeter are written in languages other than English, and while being written in (say) French or Latin isn’t itself enough to warrant inclusion in Special Collections, many of the otherwise-unique documents that we preserve and maintain are, by dint of their language of composition, much less accessible to monolingual English speakers.

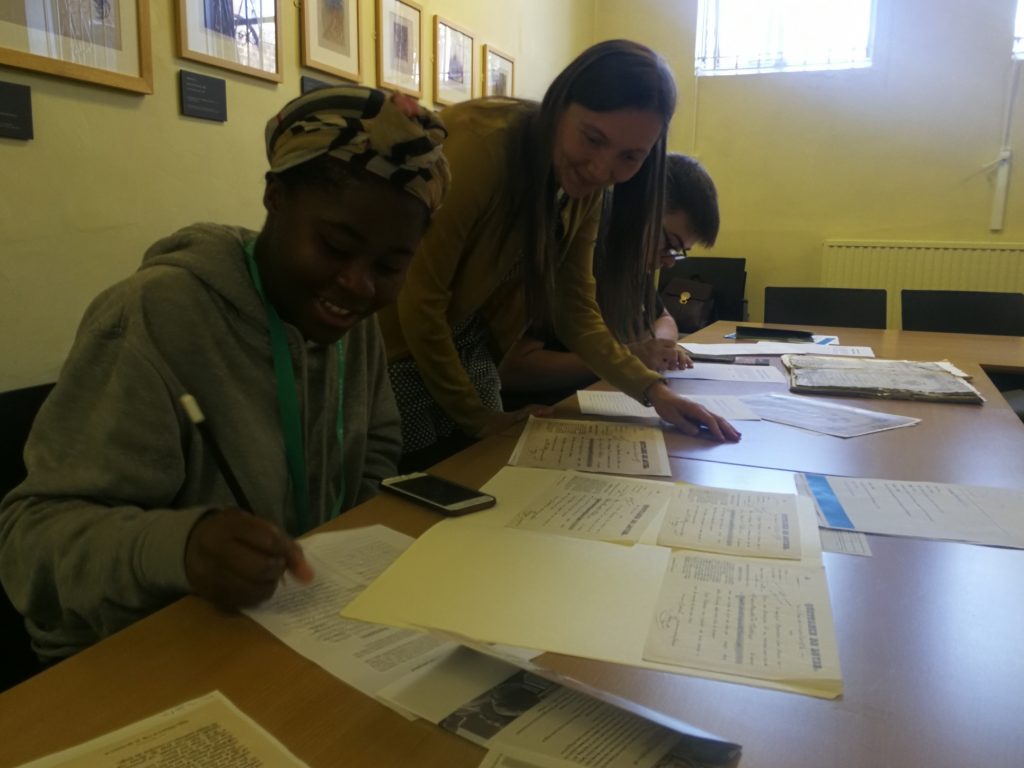

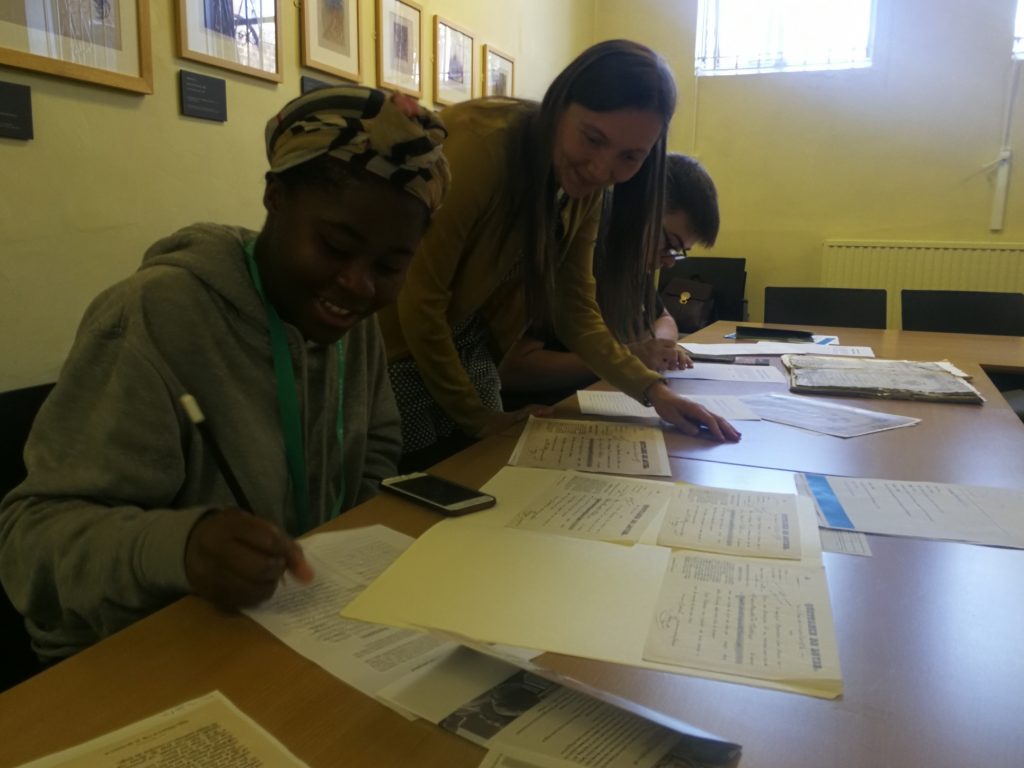

How, then, can modern linguists use their language skills in the specific context of archives? Questions like these formed the backdrop to a workshop run last week with Year 12 students from across the country, all of whom were taking part in the Modern Languages strand of the University of Exeter’s Summer Residential Programme. Accompanied by Edward Mills (a PhD student at the University) and Angela Mandrioli (a Special Collections assistant), the students spent the morning of 23rd July investigating French- and Spanish-language material in Special Collections, using their language skills to transcribe and translate these documents and working to make them available to a wider audience. In this blog post, we’re delighted to share some of the students’ work; we thank them for allowing us to reproduce their work here, and hope that it will go some way towards demonstrating the key role that languages play in the everyday life of the Special Collections Reading Room.

EUL MS 36 (box 2, item 111)

Pour le terme échu le 1er ______

Le soussigné Propriétaire d’une maison, sise à Paris, rue Montaigne no. 22, reconnais avoir reçu de Madame Mariette de Vileblun la somme de quatre cents cinquante francs pour une terme de loyer des lieux qu’occupe dans ladite maison, ledit terme échu le premier ***. Dont Quittance, sans préjudice du terme courant et sous la réserve de tous mes droits. À Paris, le 15 janvier mil huit cent cinquante six.

For the term elapsed on 1st _____

The undersigned owner of a house, located in Paris, at rue Montaigne, No, 22, acknowledges having received from Madame Marette of Nileblun the sum of four hundred and fifty francs, for one term of rent of the rooms that [she] occupies in the aforesaid house, the said term having elapsed on 1st ***. This we accept, without any effect on the current term [of rent] or my own rights. Paris, 15th January 1856.

Transcribed by Danielle Tah

This partial transcription and translation of a rent receipt is from a series of three such official documents within the Mariette family papers, which includes similar items for the months of April and July in the same year. The term ‘quittance de loyer’ might initially give the impression that the document was intended as a notice of eviction; in reality, however, the sense of ‘quittance’ here is closer to the modern English ‘calling it quits’. That’s because this document is, quite simply, a rent receipt, acknowledging that the renter (locataire) has paid their dues for the given month. Like the notarial document shown above, a rent receipt such as this also problematizes any ideas we might have about archival documents being either ‘printed’ or ‘hand-written’; it’s clear that this document is largely printed as a pro-forma, with names and amounts of money left to be written in later.

A keener look, however, reveals that the landlord didn’t quite do their due diligence in filling in all of the information required. The clue here is in the phrase ‘pour une terme de loyer des lieux qu’occupe dans ladite maison, ledit terme échu le premier’, which would translate into the distinctly odd-sounding ‘for one period of rent for the lodging that occupies in the said house, up to the first’. Who’s doing the ‘occupying’, and until the first of ‘what’ are they staying there? Judging by the gaps between some of these terms, it appears that the landlord didn’t bother to fill out a couple of blanks that are easy to miss: namely, in this case, ‘qu’elle occupe’ and ‘le premier mars’ (‘which she occupies’ and ‘the first of March’). Whether this was due to convenience or simply laziness is something that the archivist can only guess at, but it’s not something that we’d recommend pestering your own landlord about.

A student working on documents from the Mariette family papers

EUL MS 389/HOU/1/8/1 (first letter)

Ma bien chere Soeur Cecile,

Nous avons bien reçu vôtre aimable lettre du 23 octobre 92 et n’avons rien pensé du retard que vous avez mis à repondre à nôtre precedante, parce que comme que vous voyez il nous arrive la m[em]e chose ; nous avons tout nôtre temps pris nous n’avons une minute de disponible ayant comme vous de difficultées pour nous faire comprendre en français ; pour ecrire une lettre dictionnaire en main nous avons de beaucoup de temps et n’ayant pas d’occasion de pratiquer nous oublions chaque jour un peu plus le fraçais. Nous aussi nous vous ecririons beaucoup plus souvent si nous puissions le faire en espagnol.

My dear Sister Cecile,

We have received your letter dated 23rd October [18]92, and have thought nothing of your delay in replying to our last letter, since (as you can see) the same thing has happened to us; we are very busy, and don’t have a single minute free, given as how we, like you, struggle to make ourselves understood in French. It takes a very long time for us to write a letter with a dictionary in-hand, and without the opportunity to practice, we forget a little more of our French every day. We too would write to you far more frequently if we could do so in Spanish.

Transcribed by Alice Manchip and Elaria Admassu

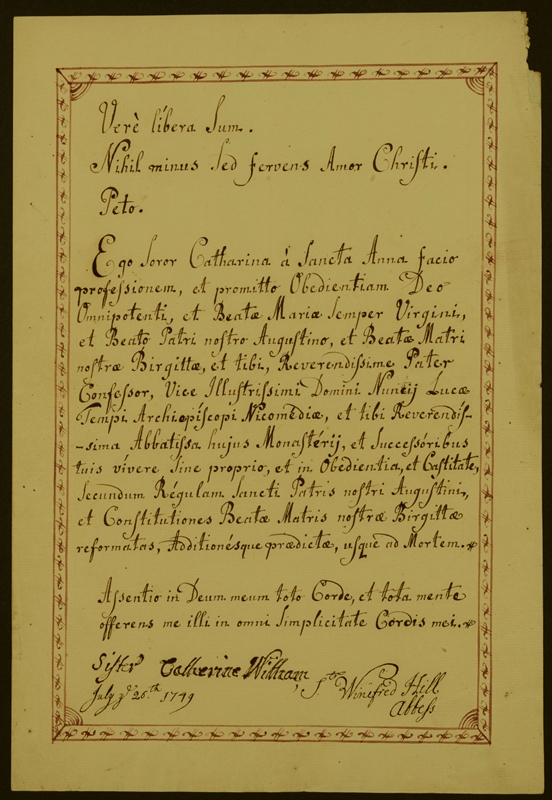

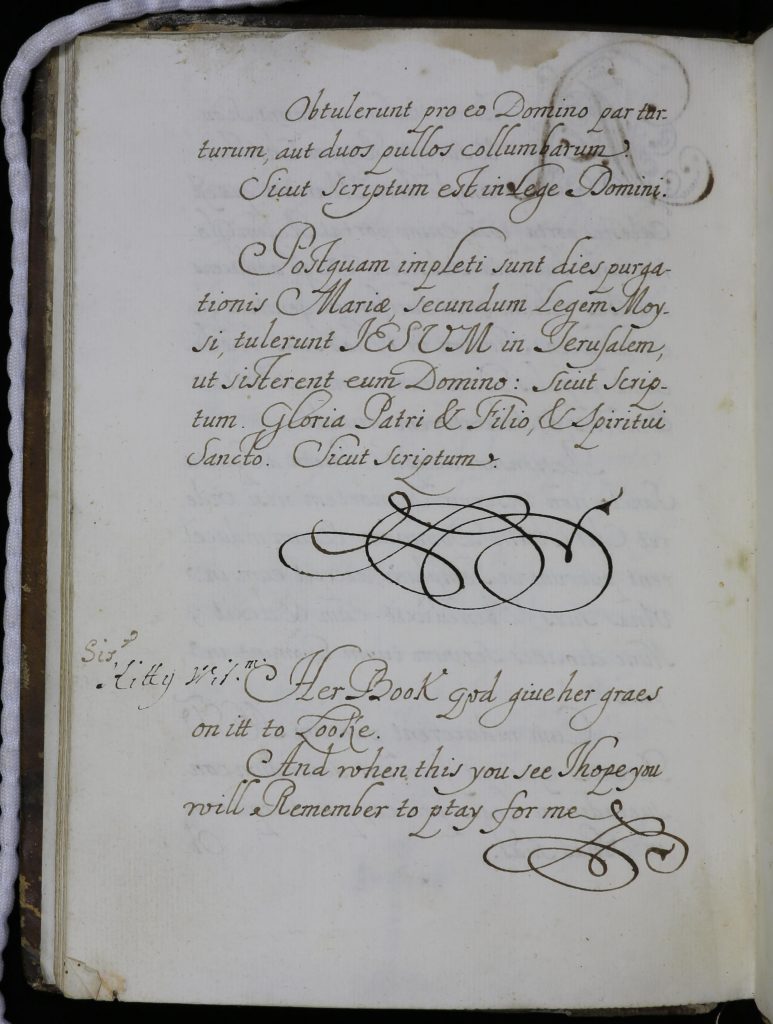

This letter, dated 7th January 1896, was written by Dolores de Marie Immaculé to her ‘sister’, Cécile. The term ‘sister’ here refers not to a family relationship, but instead to their shared membership of a religious order: specifically, the order of the Brigittines, which had religious houses in both Azcoita (modern-day Spain) and Syon Abbey (at the time located in Chudleigh, Devon). The archives of Syon Abbey now reside in the University of Exeter, and it’s in from this collection that the letter is taken. (For more information about the Syon Abbey collections, see this earlier blog post by the Project Archivist, Annie Price.)

As modern linguists, one question immediately springs to mind when reading this letter: why would a Spanish nun write to an English nun in French, especially if doing so is much harder than writing in Spanish? (After all, she needs to have ‘a dictionary to hand’!) The most likely explanation is that French is, in this instance, a vehicular language: since neither group of nuns speaks the other’s first language, French takes on the role of a common code that they can both communicate in (however awkwardly). This difficulty may also explain the four-year delay between the receipt of the English nuns’ previous letter and the arrival of the reply from Spain: the sentence immediately following this transcription reads ‘nous vous écririons beaucoup plus souvent si nous puissions le faire en espagnol.’

Incidentally, if that last sentence sounds slightly odd in French … that’s because it is. Dolores is exhibiting what linguists call ‘language transfer’, as she calques grammatical forms from her native language. Spanish uses the imperfect subjunctive in second-order conditional sentences, whereas French uses the imperfect indicative:

Les escribiríamos más frequentamente si pudiéramos / pusiésemos hacerlo en español.

Nous vous écririons beaucoup plus souvent si nous pouvions le faire en espagnol.

We would write to you far more often if we were able to do so in Spanish.

This letter, then, is interesting for all sorts of reasons: while it does provide a glimpse into personal correspondence between women in the late nineteenth century, it also, for modern linguists, shows some rather charming examples of linguistic stumbling-blocks. There are several other errors at various points in the letter, from mis-spellings to absent accents, but by and large, it’s clear here that French as a lingua franca is very much serving its purpose.

EUL MS 262/add1/3 (title page)

Suma espirituall en que se resuelven todos los casos ÿ dificultades q[ue] hay en el camino de la perfeccion. Compuesta por el Padre Figueras, religioso de la companía de iesus, confessor del conde de Benevente

A spiritual summe in which bee resolved all the difficulties and cases that maie happen in the waie of perfection. Composed by the Reverend Father Figueras of the Societies of iesus and Confessor to the Earle of Benevente

Transcribed by Muning Limbu

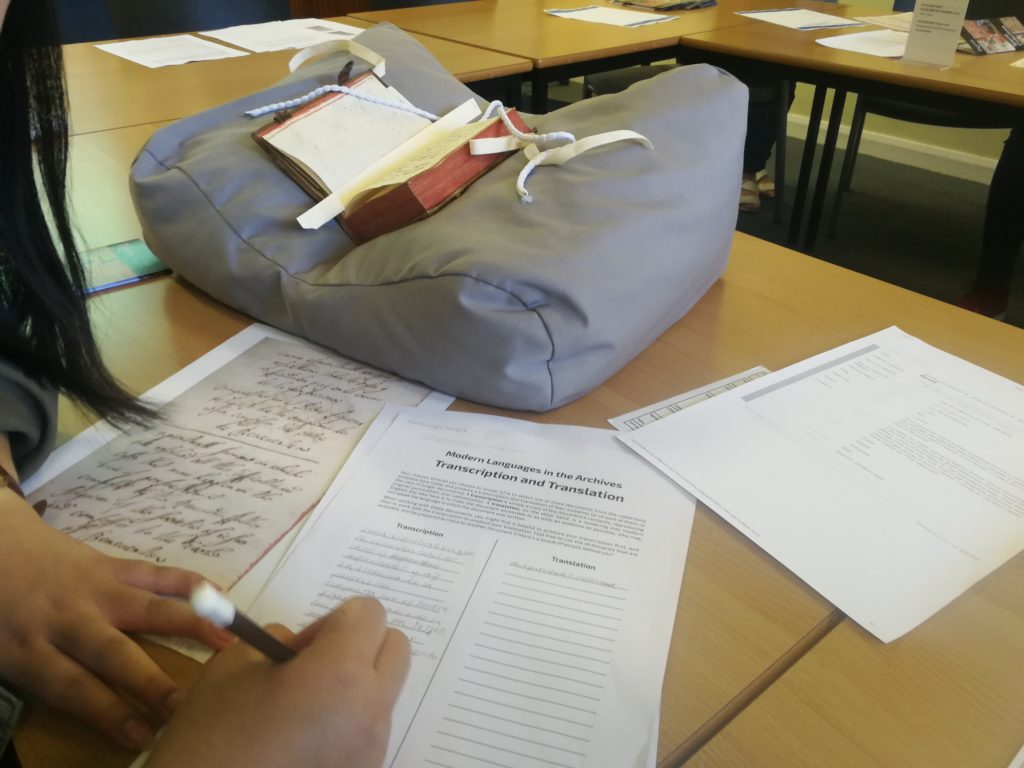

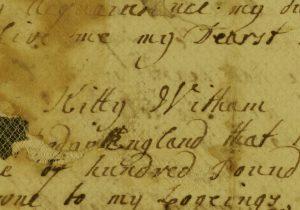

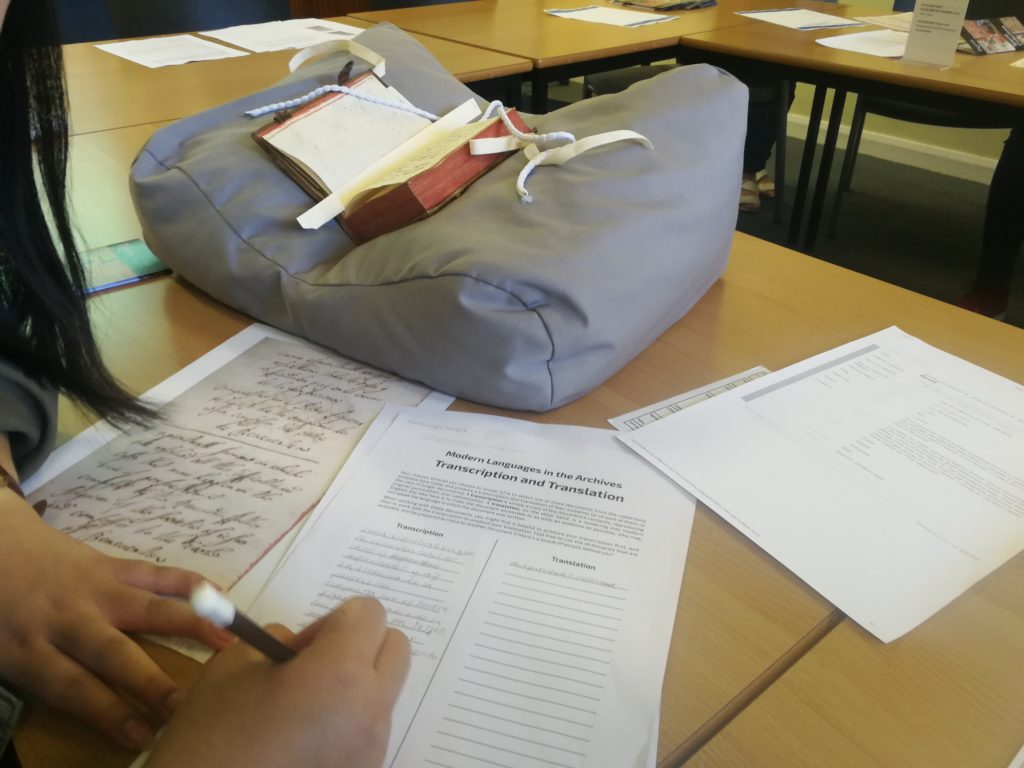

This manuscript is also from the Syon Abbey collection, but predates the letter to Cécile by almost 250 years. Datable to 1657, it’s surprisingly small — measuring approximately 145 x 100mm, and featuring clasps — and contains three ‘treatises’, each of which has been foliated separately by a contemporary hand. The extract above is taken from the title page, which presents both the original Spanish title of the work and its translated title in English; it is not, however, the first page of the book, as it is preceded by a dedicatory epistle from the translator. Naming himself as ‘Brother Francis’, he explains that the work was produced at the request of Sister Ellen Harnage, ‘in the Monasterie of the most devout religious English Nunnes of Syon in Lisbone’. he apologises if his work seems a poor substitute for the original: ‘there is a great difference betwixt a tailor and translator, yet sure I am, the loome is the same, though not the lustre, the substance, though not the varietie of colours, sweetness of speech, and quaint language’. These linguistic anxieties may go some way towards explaining Francis’ decision to retain the original title on the following folio, but from a linguistic perspective, the co-existence of multiple languages also provides a valuable insight into the early modern orthography of both Spanish and English.

In addition to this volume, which was produced for her benefit, Special Collections also holds her (bilingual English-Portuguese) vows of profession to join the community, in which she spells her name ‘Ellin’ (dated 1st January 1642). In 1681, as a collection of miscellaneous Syon Abbey documents records, she became Prioress of the Abbey, a position that she held until her death in 1683.

A student working on a manuscript from the Syon Abbey Collection

EUL MS 56 (opening folio)

Venta de nueve minas de oro sitas en termino de la Nava de Jadraque. Ayuntamiento del Ordial partido judicial de Atienza en la provincia de Guadalajara. Otorgada por Don Mancino Magio y Castillo, y otros a favor de La Compañia Española Limitada de minas de oro y Plata de Guadalajara, representada por los Señores Don José Morrell y Earle y Don Juan Hennon y Hackworth; ante Don Ramon Sanchez Suarez, Notario del Colegio de Madrid.

Sale: of nine gold mine sites at the edge of the Jadraque flatland, within the jurisdiction of the borough of Atienza, in the province of Guadalajara. Given by Don Mariano Magro y Castillo, and others, to the Compañia Española Limitada de minas de oro y Plata de Guadalajara, represented by Messrs. Don José Morrell y Earle, and Don Juan Hennon y Hackworth; before Don Ramon Sanchez Suarez, Notary of the Colegio de Madrid.

Transcribed by Joe Sene

Mining documents might not, at first glance, appear to be the most riveting of the Spanish-language material held in Special Collections. Nevertheless, this particular piece part of a much larger collection of items relating to mining operations throughout the nineteenth century — is intriguing for several reasons. The most obvious of these is its size: as a large document with clearly defined borders (310 x 220mm, with the enclosed area totalling 255 x 165mm), it serves a clearly-defined purpose as a frontispiece for the collection as a whole. Also of note is its construction: while the border, the name of the notario, and the seal of the Colegio de notarios are printed, everything else is carefully written by hand in a legible, italic script. This is a document designed to illustrate the legal status and authority held by Don Ramón Sanchez Suarez, and it does this elegantly through a mixture of print and manuscript. One can almost imagine Don Ramón reaching for a stack of these forms from his desk as he begins to draft the document itself.

The story behind the Guadalajara Gold and Silver Mining Company of Spain is, incidentally, an interesting one (stay with me here). The company — based out of the UK — was formed in 1879 in response to a promise of a gold rush in the area; unfortunately, these claims turned out to be optimistic, and the Company seems to have folded in 1895. This document, then, was woefully optimistic; hopefully modern linguists making use of their language skills in a business context will make better decisions than Messrs. Morell and Hackworth.

EUL MS 207/2/1/1 (mounted ink drawing and letter)

Chère Carrey,

La nuit, l’imagination de Georges prend le costume d’un chasseur antique, pardessus lequel il met une paire de caleçons […] affublé de la sorte, il va à la chasse […] dans les vastes forêts de la memoire […]. Ces curieuses forêts sont peuplés d’êtres fantastiques et d’arbres singuliers …

Dear Carrey,

At night, George’s imagination dresses up like an old-time hunter, over which he puts on a pair of leggings […] suitably dressed-up, he goes out hunting the […] in the vast forest of memory […]. These curious forests are populated by fantastical creatures and remarkable trees …

Transcribed by Temi; reproduced by kind permission of the Chichester Partnership

This nineteenth-century letter from Georges du Maurier to the unidentified ‘Carrey’ is dominated by an ink drawing, which portrays a Robin Hood-esque figure resplendent in tights and carrying a bow as he looks upon three figures (likely those named in the letter itself). While the current presentation of the item — mounted on cardboard — does help to foreground the intricate image, it has an unfortunate side-effect: namely, that many readers leave unaware that the letter also has a verso side. This verso side offers something of a counterpoint to the vivid, imaginative dreamscape painted on the recto side, as Georges apologises for writing ‘toute pleine de bêtise[s]’ (‘all kinds of nonsense’) and thanks Carrey for her previous letter. Even if the drawing dominates the item today, then, the content of the letter itself — which Modern Languages researchers are uniquely well-suited to unpick — illustrates a side to Georges du Maurier’s personality that might not otherwise be visible. His whimsy and active imagination are on full view here, as he imagines this vivid scene and escapes from the noises and distractions that surround him.

The five items investigated in this blog post are, of course, only a snapshot of what’s accessible in the archives. Even in and of themselves, though, they go some way towards demonstrating the range of languages and genres that can appear in a Special Collections reading room, as well as illustrating the essential role that language skills play in helping to interpret them. For the Year 12 students, it was precisely these language skills that unlocked the documents, and brought history to life, whether professional mining transactions or deeply personal letters. Archive work might not be what most students are expecting when considering studying Modern Languages at university, but as this session showed, the skills developed by a languages degree – from the obvious linguistic aptitude to the lesser-anticipated intercultural competence and ability to place language use in context – can be applied in a wider range of areas than one might think.

Transcriptions and translations by students on the ‘Modern Languages: Translating Cultures’ strand

of the University of Exeter Year 12 Summer Residential

Text by Edward Mills, PhD student (Department of Modern Languages)