Student volunteer and PhD student Charlie Clark‘s new exhibition of items from the University of Exeter’s Special Collections explores the relationship between magic and civil law, from the 16th century to present day. You can find the exhibition in the display case on Level 0 of the Forum Library on Streatham Campus.

Introduction

Much has already been said about the persecution of so-called ‘witches’ in early-modern Europe. Between 1542 and 1736, the introduction and enforcement of the Witchcraft Act in England and Wales meant that the civil arm of the law was responsible for prosecuting individuals suspected of its practice. The accused, disproportionately women, were blamed for causing a range of undesirable circumstances, including illness and death, at Satan’s behest.

However, the story does not end with the repeal of the Witchcraft Act in 1736. Self-proclaimed ’witches’, or individuals practising ‘witchcraft’ or ’sorcery’, first sought legal recognition and protection in the UK in the twentieth century. Consequently, practitioners reclaiming such terminology continue to engage with one another, with the latter often appealing to the memory of the witch trials to assert their rights. Meanwhile, witchcraft trials continue to take place in the contemporary world. People still alive today have been the focus of accusations, ordeals, and subsequent punishments for their perceived guilt.

This new exhibition of items from the University of Exeter’s Special Collections seeks to raise awareness of the continued relationship between magic and civil law. It first explores early-modern witch trials in England, focusing on the Bideford witch trials that took place in Exeter and the introduction of legal protections for self-proclaimed ‘witches’. The exhibition will conclude with an examination of witchcraft trials in twentieth-century Socotra, demonstrating that such accusations continue to impact communities today.

Witchcraft in Early-Modern England

Discussions concerning witch-hunting in early-modern England should begin with the introduction of the Witchcraft Act in 1542. This law, and its successors (1563, 1604), made civil authorities rather than ecclesiastical ones responsible for the extermination of heretics employing “witchcrafts enchauntmentes or sorceries” (An Act against Conjurations, Witchcrafts, Sorcery and Inchantments; Great Britain Parliament House of Commons, vol. 1). Thus, anyone suspected of using witchcraft to procure knowledge or wealth, or to harm others, would be executed. This was ratified by King James I in 1604 (Acts of the Parliament of Scotland, vol. 4), reemphasising the need to expunge Christian society of witches, who were understood to act at the behest of the Devil. Indeed, King James possessed a keen interest in witchcraft, authoring the Daemonologia (not displayed in this exhibition, but available via the University of Exeter’s Special Collections).

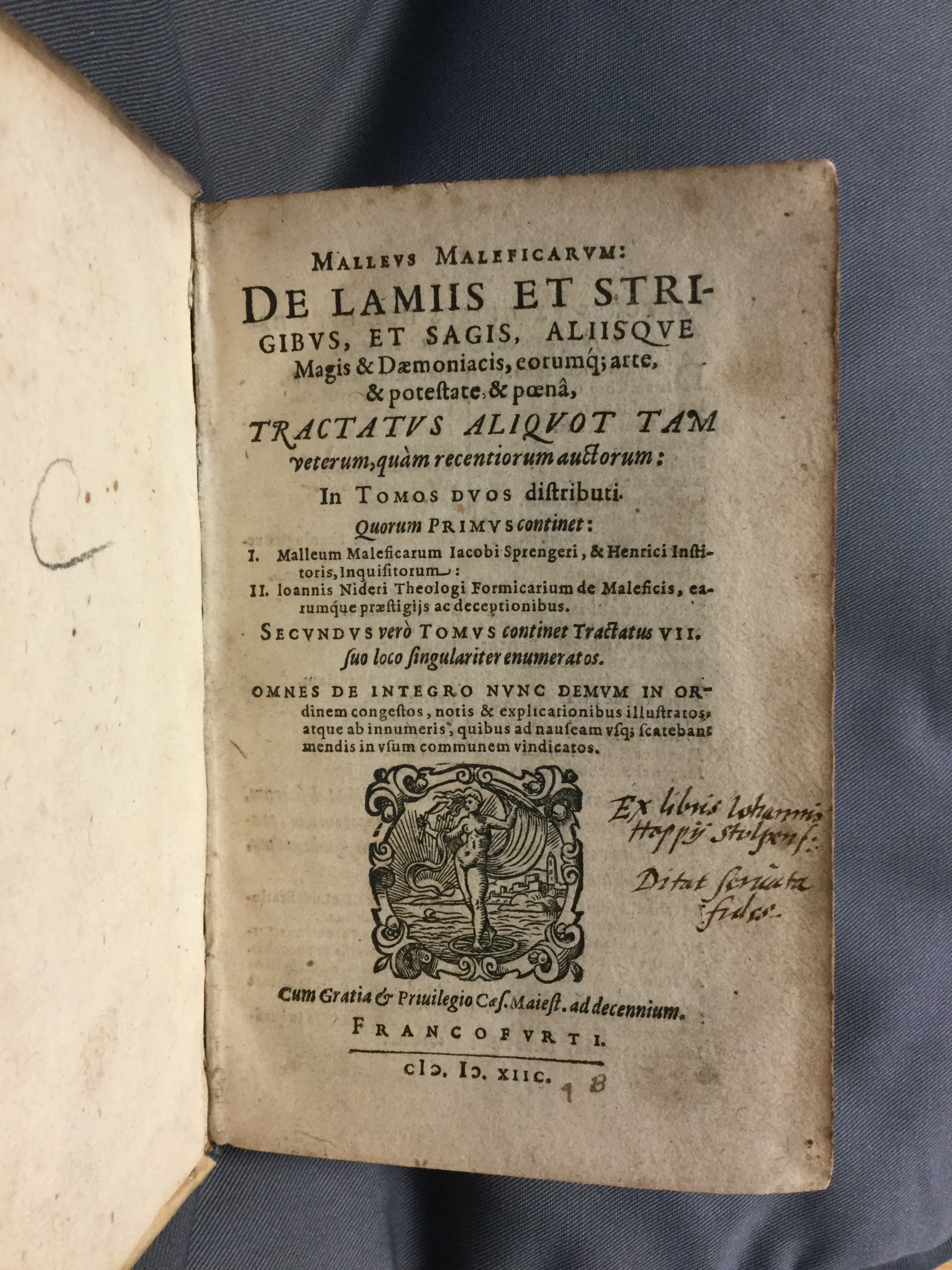

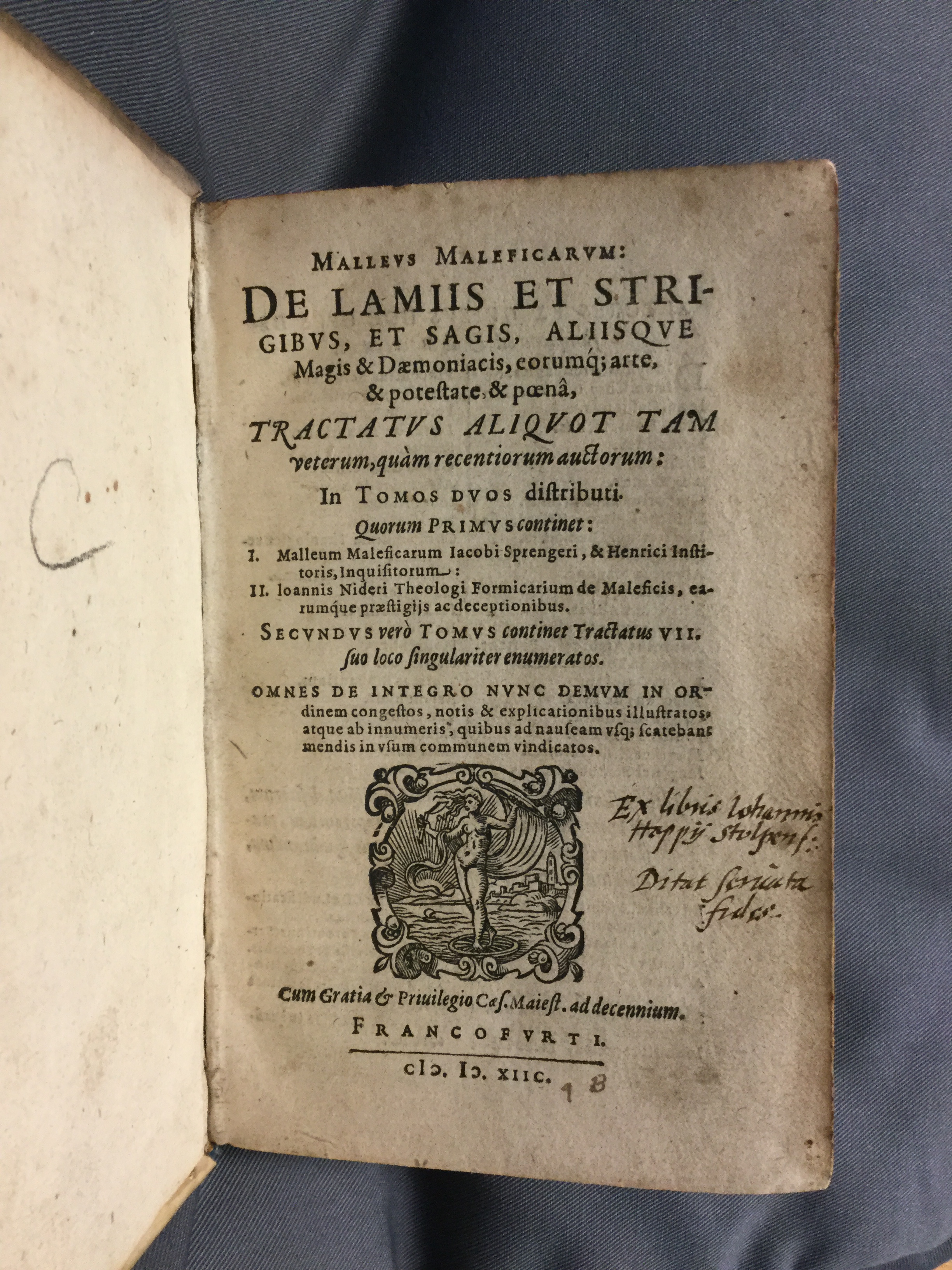

Such perceptions of the capabilities of and dangers posed by witches, as well as the desire for civil authorities to handle such cases, were codified by the Malleus Maleficarum, “The Hammer of the Witches”, which greatly influenced the later introduction of the Witchcraft Act (Gent, 1982 – Edmund pamphlet 942.359/B40 GEN). Written and published by Heinrich Kramer in Speyer in 1486, the text is divided into three sections. The first is concerned with proving that the heresy of witchcraft exists; the second discusses the powers possessed by witches; and the third describes the ‘appropriate’ procedure for prosecution. Hearsay and other non-verifiable sources of evidence were enough to justify the accusation and arrest of suspects, who tended to be women who occupied socially ambiguous or marginalised positions, such as widows and midwives. The guilt of the accused would be assumed; if the woman maintained her innocence, a confession would be forced by torture “so that the truth will be had from [her] mouth and [she] will no longer offend the ears of the judges” (trans. Mackay, 2015). If the accused did not confess, they would be told that a confession would spare them the death penalty. The Malleus confirms that this was a lie, as it enjoins civil authorities to prescribe death to all those suspected of practising witchcraft, proclaiming “extermination to heretics” (trans. Mackay, 2015). The manuscript on display (Baring-Gould Library 0495) was copied in 1588. Its faded cover and fragile binding, as well as its late production date, bear witness to the popularity and longevity of beliefs surrounding witchcraft during this period.

Prior to the publication of the Malleus, there are few records that describe the prosecution of witches. A surge in the number of trials and prosecutions follow its publication, further demonstrating its widespread impact. Indeed, accusations, trials and death sentences across England typically followed the pattern laid out by the Malleus Maleficarum. One such trial occurred in Devon in 1682, commemorated on a plaque in Heavitree. Gent (1982, Edmund pamphlet 942.359/B40 GEN) recounts how Temperance Lloyd, Mary Trembles and Susanna Edwards were arrested and tried for witchcraft following sensationalised accusations that they had caused illnesses and death, possessed “carnal knowledge” of the Devil, and could perform supernatural acts including shapeshifting. The trial was held at the Exeter Assizes amid much publicity. As the Malleus prescribed, hearsay and public animosity comprised much of the evidence against the accused, and they were manipulated into giving confessions. They were found guilty on the 14th of August and hung eleven days later.

The final execution of a so-called ‘witch’ occurred in 1712, with the victim later royally pardoned (Gent, 1982, Edmund pamphlet 942.359/B40 GEN). The Witchcraft Act was finally repealed in 1736 (Great Britain Parliament House of Commons, vol. 24), marking the end of the witch-hunt craze in England. However, the relationship between ‘witchcraft’ and secular law did not conclude here; rather, it continued further into modernity.

Contemporary Witchcraft: England

An increasing number of individuals, typically adherents of paganism and related faiths, self-identify as witches and practitioners of witchcraft. As a result, several groups have formed to promote and defend the legal recognition and protection of their members. Whilst it’s unclear how many of today’s witches identify with persecuted individuals in early-modern England, proponents of pagan rights continue to cite historic trials and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights when advocating for their rights (and rites!) (EUL MS 105/29). Their success sharply contrasts the fervor of the witch hunts a mere three centuries prior.

One such group is the Pagan Front – now known as the Pagan Federation – which was formally established in 1971. Their manifesto, written in 1970, outlines their beliefs and aims. Confidently self-identifying as ‘witches’, the Front acknowledges that, while “past persecution and intolerance” may hinder their public acceptance, “Witches and other Pagans are people, too, and have the same human and civil rights as anyone else” (EUL MS 105/29, emphasis added). Thus, a primary concern of theirs has been to enjoin civil law to protect witches and practitioners of witchcraft.

Indeed, self-identified witches began to use their newfound legal protections to their benefit. An open letter to the Secretary of State for Home Affairs, dated the 20th of March 1970, detailed a defamation case against the press (EUL MS 105/29). The Pagan Front referred to false claims that a Wiccan had lured a teenager into witchcraft to seduce her; this accusation had resulted in the destruction of private property belonging to pagans. The letter implied that the Witchcraft Act and its consequences continued to loom over the pagan community – referring to the “repeal of the anachronistic Witchcraft Act”, the letter implores the addressee to understand that the witchcraft practised by modern pagans is not harmful, despite the claims of the Malleus and related texts.

The result of the case described above is unclear. However, the twenty-first century has witnessed a significant progression in the rights of self-proclaimed witches. The 2010 Equality Act protects people of any (or no) faith, including pagans, from discrimination, harassment and victimisation (Legislation.gov.uk). This has resulted in legal cases that would have been unimaginable in early-modern England. Notably, a witch called Karen Holland claimed that she was unfairly dismissed from her job for attending a Halloween festival. The court ruled that the dismissal was indefensible based on religious discrimination and awarded her £15,241.28 (‘Holland v Angel Supermarket Ltd and Anor’, 2013). While it may be the case that witches continue to face discrimination, the law is now on their side.

Contemporary Witchcraft: Socotra

Unlike the English witch hunts, the prosecution of so-called ‘witches’ in Socotra endures in living memory. ‘Witches’ – exclusively women – were tried and excommunicated by law in Socotra, an island currently under Yemeni jurisdiction, until the end of the Sultanate period in 1967 (Peutz, 2009). Accounts detail trials by ordeal and subsequent banishments, which have had an enduring impact on the accused and their families.

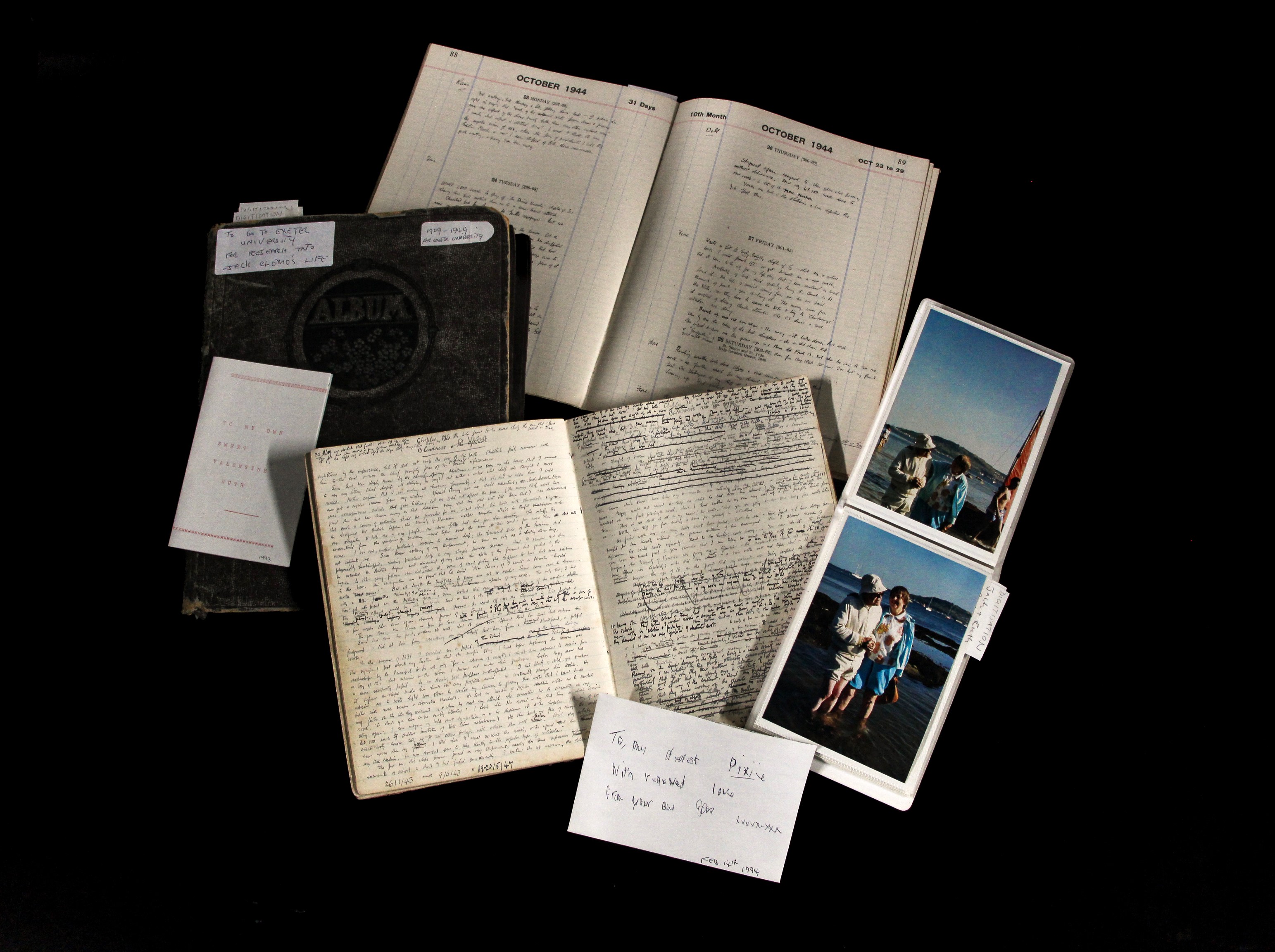

John Carter, in his writings on Omani witchcraft (EUL MS 476/1/7), recounts the typical legal proceedings following an accusation of witchcraft in the 1950s. Every year, between fifteen to twenty women would be sent to Hadibo, the capital of Socotra, to be put on trial. If the accused maintained her innocence, the Sultan, who oversaw the law courts, would recommend a trial by ordeal, carried out by a well-reputed Muslim. The accused would be tied up with rocks, taken out to sea and dunked at a depth of fifteen feet. If she hit the seabed three times, she was considered innocent. If she floated back to shore, she was deemed guilty and forced onto the next departing vessel to be exiled. Her children couldn’t go with her. Carter witnessed one such trial of three women in 1955. One admitted her guilt prior to the ordeal, whilst the others were found guilty. All three women were excommunicated, and thus cut off from their families.

The consequences of these trials reverberate even today, sometimes in unexpected ways. Peutz (2009) spoke to both a woman excommunicated on account of her perceived practise of sorcery, and her family back in Socotra. She, like many other banished women, did not openly discuss the reasons for her exile. She continues to support the Socotran economy by sending home monetary gifts, some of which have been used to build important structures including mosques. Meanwhile, her family do discuss the reasons for her banishment – which, at first glance, is unexpected. The Socotran government and populace outwardly treat their “traditional” but “erroneous” beliefs in witchcraft and sorcery (as cited in Peutz, 2009) with palpable embarrassment, referring to the relevant period as the “regime of ignorance” (Peutz, 2009). Despite this, though no longer punishable by law, rumours of its practice still circulate amongst locals. There is no legal protection for anyone who may choose to self-identify as such.

Conclusion

This exhibition has sought to raise awareness of the continued relationship between witchcraft and civil law – not only in Europe, where the history of witch-hunts is well known, but elsewhere in the world. As we have seen, English witches appeal to past persecutions to advocate for their civil rights, which has resulted in the introduction of legal protections. Meanwhile, although witch trials are no longer legal in Socotra, the victims of accusations and their families continue to live with the consequences of persecution and now-defunct laws that targeted so-called ‘witches’. Thus, laws regarding witches and witchcraft continue to impact communities in the contemporary world.

To discover more about these objects, visit the Subject Guide for Esotericism and the Magical Tradition LibGuide here .

Bibliography

‘An Act against Conjurations, Witchcrafts, Sorcery and Inchantments’. [n.d.]. <https://digitalarchive.parliament.uk/book/view?bookName=An%20Act%20against%20Conjurations,%20Witchcrafts,%20Sorcery%20and%20Inchantments&catRef=HL%2fPO%2fPU%2f1%2f1541%2f33H8n8&mfstId=15b0be56-3940-41f6-a0f9-e3e3e2174d80#page/n1/mode/1up> [accessed 7 February 2025]

Great Britain Parliament House of Commons. Journals of the House of Commons. 249 vols(London)

‘Holland v Angel Supermarket Ltd ET/3301005/13’. [n.d.]. Practical Law <https://uk.practicallaw.thomsonreuters.com/3-553-1785?contextData=(sc.Default)&transitionType=Default&firstPage=true> [accessed 7 February 2025]

Legislation.gov.uk. [n.d.]. ‘Equality Act 2010’ (Statute Law Database) <https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2010/15/contents> [accessed 7 February 2025]

Mackay, Christopher S. (trans.). 2009. The Hammer of Witches: A Complete Translation of the Malleus Maleficarum, 1st ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press)

Peutz, Nathalie Mae. 2009. ‘Heritage and Heresy: Environment, Community, and the State at the Margins of Arabia’ (unpublished Ph.D., United States — New Jersey: Princeton University) <https://www.proquest.com/docview/304986625/abstract/B7D543D243894FC5PQ/1> [accessed 7 February 2025]

Scottish Parliament. 1814. The Acts of the Parliaments of Scotland, 1124-1707, Record Commissioners Publications, vol. 4 (London: Record Commission)