During the first six months of the Common Ground archive cataloguing project, I examined and briefly described the material I found in each file within the archive to create a comprehensive box list. This new box list now provides me with a good overview of the contents of the archive, which – I hope! – will vastly facilitate the cataloguing process. Keen to finally get down to some proper cataloguing, I decided to tackle the archive material relating to two of Common Ground’s early projects: Second Nature and Holding Your Ground.

EUL MS 416/LIB/1 – Books: ‘Second Nature’ (1984) and ‘Holding Your Ground (1987)

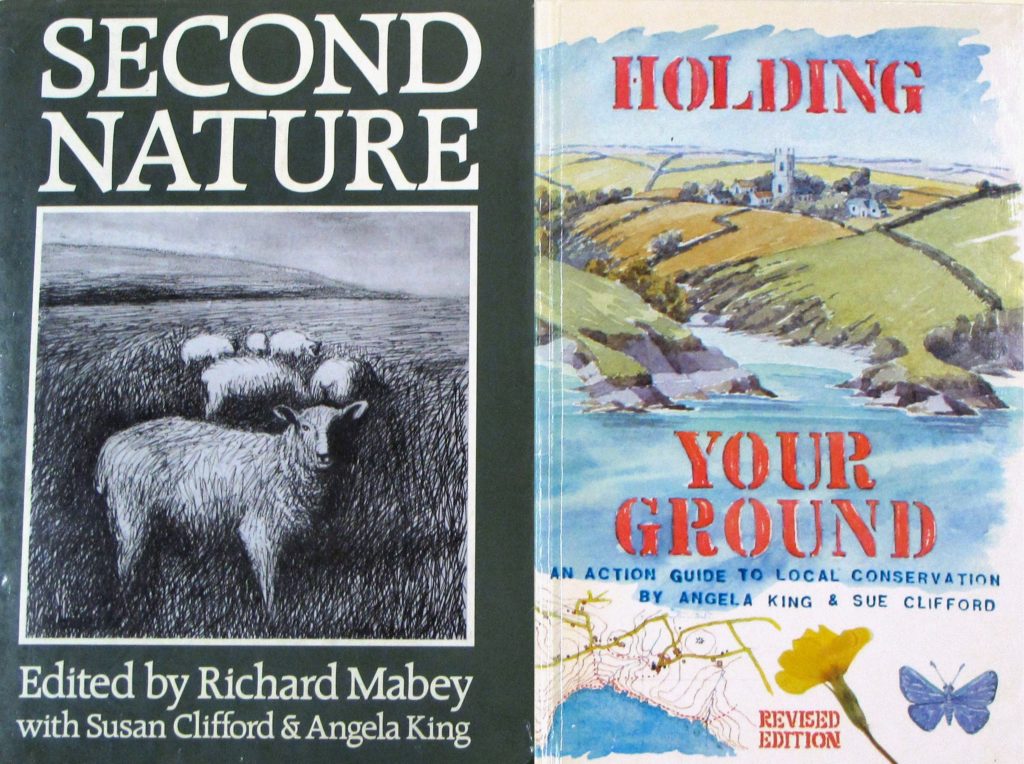

The Second Nature project concerned the publication of a collection of essays and artwork. 42 writers and artists were invited by Common Ground to ‘express their feelings about Britain’s dwindling wild life and countryside’ (‘Second Nature’, 1984) and contribute to this anthology through prose, poetry or art. The book was edited by Richard Mabey with Sue Clifford and Angela King – the three founders of Common Ground – and published by Jonathan Cape in 1984. Three public seminars at the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) took place in October and November 1984 to discuss the themes explored in the book. The artwork featured in ‘Second Nature’ was exhibited at the Newlyn Orion Gallery in Penzance in 1984, and subsequently travelled to other venues.

EUL MS 416/PRO/1/1/1 – Small cards with names of contributors, presumably used to plan the layout of ‘Second Nature’

One year after ‘Second Nature’ was published, Sue Clifford and Angela King co-authored and published a second book together: ‘Holding Your Ground: an action guide to local conservation’. It was first published by Maurice Temple Smith in 1985, and a revised edition was published by Wildwood House in 1987. The book provides information on how to care for your locality, reasons why local conservation is important, case studies of local initiatives, and advice on who to contact for help and support. The book includes a foreword by David Bellamy, artwork by Tony Foster and Robin Tanner, and photography by Chris Baines, Ian Anderson and Ron Frampton.

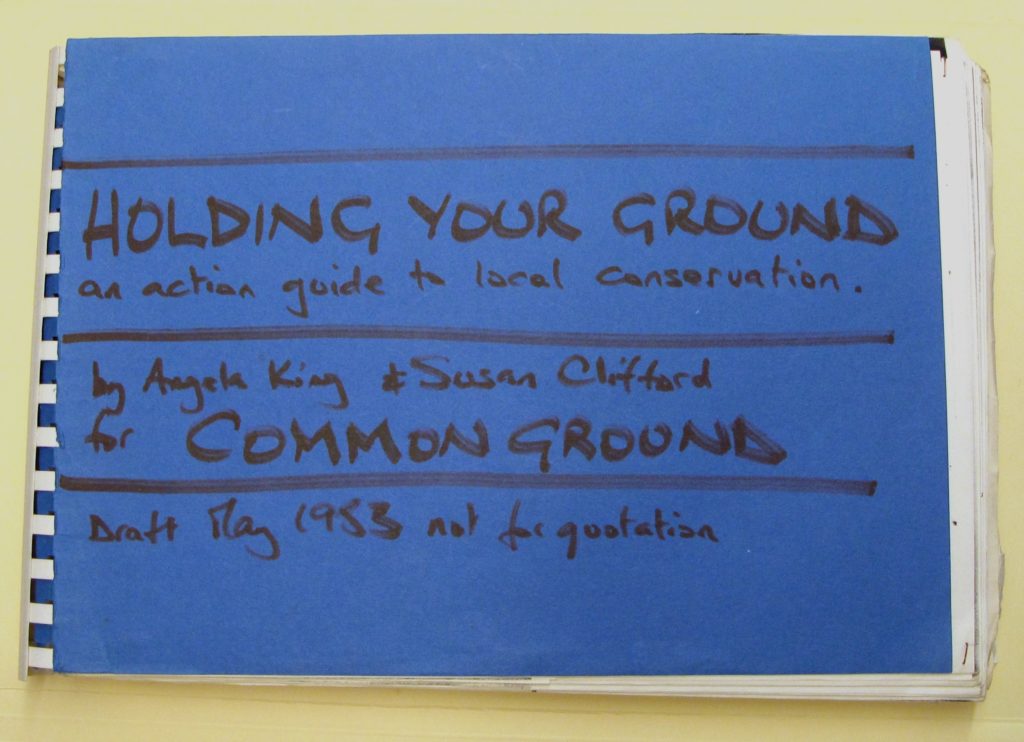

EUL MS 416/PRO/2/1/1 – Comb-bound typescript draft of ‘Holding Your Ground’ (1983)

These early projects highlight the two strands of Common Ground’s work which informed the projects that followed; firstly, collaborating with artists and writers to reflect on our relationship with nature, and secondly, encouraging people to take action in looking after their local environment. Using the arts to celebrate local distinctiveness, encourage people to emotionally engage with their surroundings, and consequently interest them in conservation at a local level would become the cornerstone of Common Ground’s work.

EUL MS 416/PRO/2/2/3 – File of research material relating to ‘Parish Initiatives’ for the ‘Holding Your Ground’ project

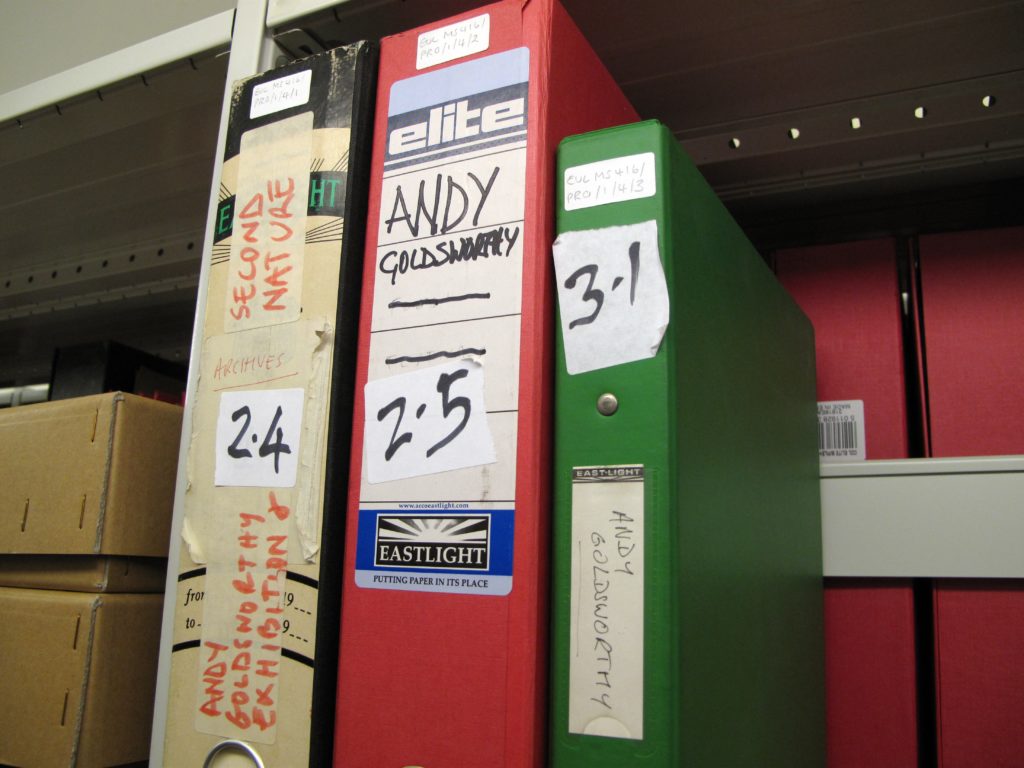

In addition, many of the relationships Common Ground forged with artists and writers at this very early stage would prove to be long lasting and influential. For example, the artist Andy Goldsworthy, who provided five photographs of his artwork for ‘Second Nature’, completed a residency on Hampstead Heath supported by Common Ground in the winter of 1985-1986, and would go on to work with Common Ground on various other projects, including Trees, Woods and the Green Man, New Milestones, and Rhynes, Rivers and Running Brooks. Other artists and writers who worked with Common Ground again after collaboration on these early projects include: Norman Ackroyd, Conrad Atkinson, John Fowles, David Nash, James Ravilious, and Tony Foster.

EUL MS 416/PRO/1/4 – Files relating to projects with the artist Andy Goldsworthy

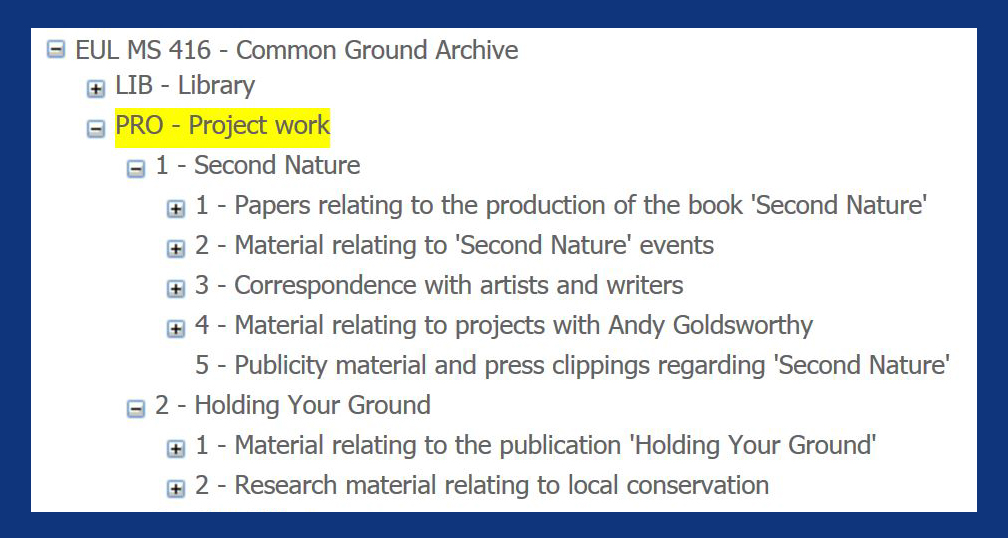

Material in the Second Nature section of the archive includes: correspondence with artists and writers; papers concerning the production of the book; papers relating to the seminars held at the ICA; papers concerning the exhibition of artists’ work; and several files of papers relating to Common Ground’s collaboration with artist Andy Goldsworthy, in particular: his residency on Hampstead Heath and exhibitions of his work. The ‘Holding Your Ground’ section of the archive comprises drafts of the book ‘Holding Your Ground’, book reviews, correspondence and research material. All of this material has now been catalogued and descriptions of the files and items are available to browse online via our archives catalogue.

Catalogue entries for ‘Second Nature’ (reference number: EUL MS 416/PRO/1) and ‘Holding Your Ground (reference number: EUL MS 416/PRO/2) on the Special Collections online archives catalogue

Having now completed the cataloguing of two relatively small sections of Common Ground’s project work in the archive, I’m giving myself a slightly bigger challenge to catalogue next: material relating to the Parish Maps project. The Parish Maps project was launched by Common Ground in 1987 to encourage people ‘to share and chart information about their locality as a first step to becoming involved in its care’ (Common Ground leaflet, 2000). The project output included two exhibitions, several publications, and thousands of maps created in various forms by individuals, groups, schools, councils, communities and organisations – so I will certainly have my work cut out!

Thanks for reading – until next time!

By Annie, Project Archivist

Why not start your exploration of the Common Ground archive via our online archives catalogue today?

Click here to browse the section ‘Second Nature’ via the online archives catalogue.

Click here to browse the section ‘Holding Your Ground’ via the online archives catalogue.

You can also find out more about the Common Ground archive cataloguing project by taking a look back at our previous blog posts.