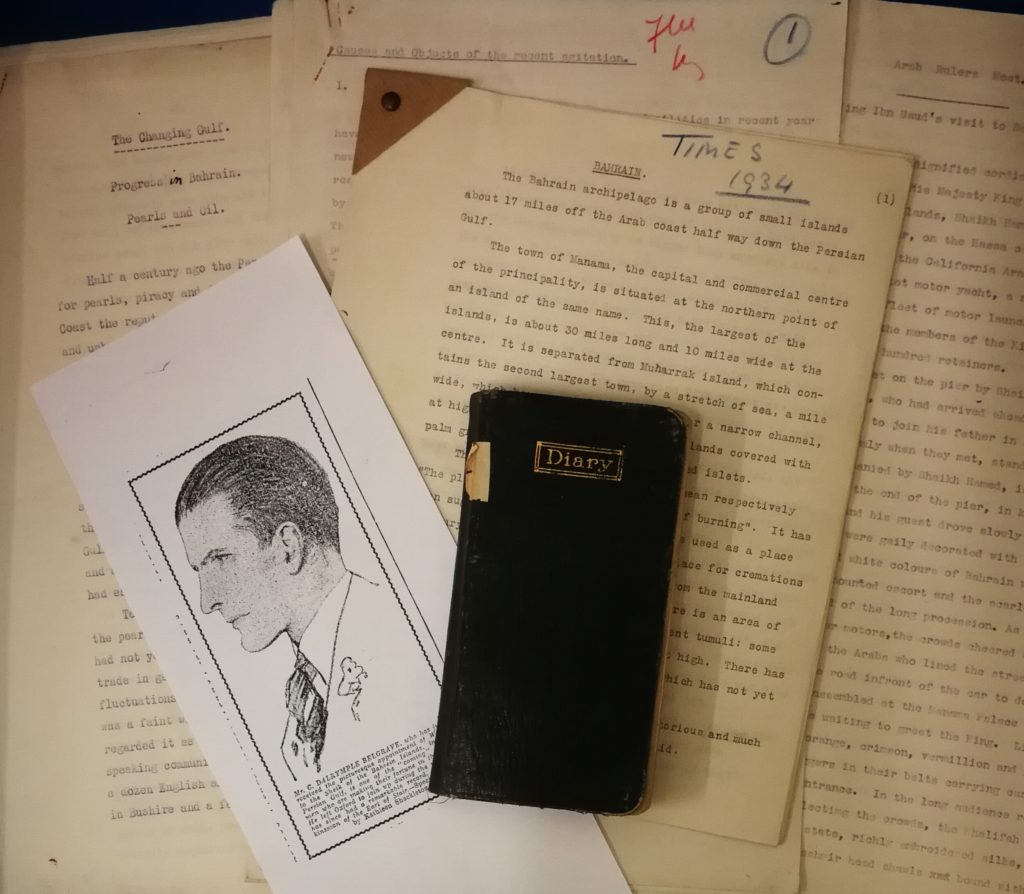

Belgrave’s diary for 1917 along with articles on Bahrain written for ‘The Times’ EUL MS 148/2/1/2 and 10

One reason why the papers of Charles Dalrymple Belgrave provide such a fascinating resource is the distinctive nature of his career in the Gulf. Most of the diplomats whose papers are preserved in the Middle East Collections served in specific roles – such as ambassador or political resident – under the British government, and tended to move from place to place every few years. Belgrave was appointed as ‘Adviser’ to the Sheikh of Bahrain in 1926 and held this post until 1957. This thirty-year period saw Bahrain transformed by the discovery of oil and a series of modernising administrative reforms led by Belgrave, who oversaw improvements in the legal system, infrastructure, police service and public health. As he was an employee of the Sheikh rather than the British government, Belgrave occupied a unique and somewhat ambiguous position, balancing the interests of the Al Khalifa rulers and the Bahraini people with Foreign Office policy and British strategic aims for the Gulf region. The papers in our collection shed light not only on the achievements, challenges and controversies of Belgrave’s life and work in Bahrain, but also reveal the means by which the society and economy of this small island altered dramatically during this time, and the role played by British and American interests – both political and commercial.

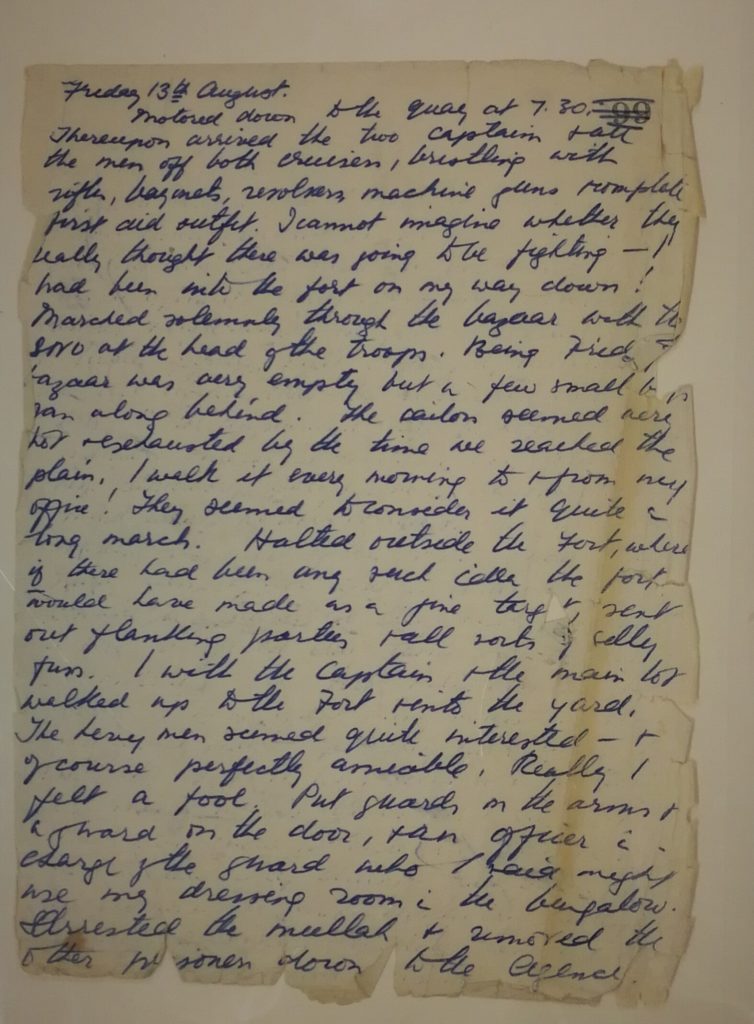

Pages from Belgrave’s diary for 13 August 1926, recording events in the wake of a fatal shooting at The Fort, the police headquarters. The Political Agent, Major Clive Daly, was badly wounded in the incident – hence the arrival of the cruiser referred to above, which Belgrave clearly regarded as an over-reaction. EUL MS 148/2/2/6/4

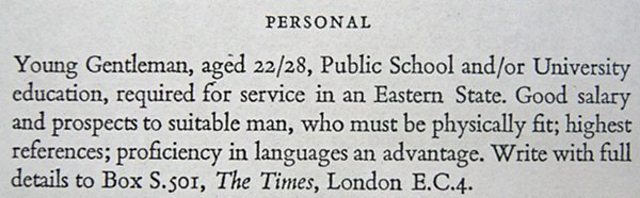

Prior to his appointment as Adviser in 1926, Belgrave had obtained experience of the Middle East through military service with the Imperial Camel Corps Brigade during the First World War in Egypt, Sudan and Palestine. He then held administrative posts in the Siwa Oasis in Egypt – recorded in his book Siwa: The oasis of Jupiter Ammon (London: Bodley Head, 1923) – and Tanganyika (formerly German East Africa, now part of Tanzania). It was while on leave from East Africa that he saw a job vacancy in the ‘Personal’ adverts of The Times (10 August 1925) – a life-changing moment that gave its name to his autobiography Personal Column (London: Hutchinson, 1960) and also featured in one of Belgrave’s watercolour paintings, a photograph of which is in our collection (EUL MS 148/2/2/4/1).

Having secured the job after interviews with British government officials, Belgrave undertook a three-month Arabic course at the School of Oriental and African Studies in London and tried to find out what he could about Bahrain – only to discover that very little information was available. After marrying his fiancée Marjorie Lepel Barrett-Lennard on 27 February 1926, the Belgraves sailed for Bahrain, arriving on 31 March which is when his diary starts.

It should be noted at this point that – with the exception of a few small sections – the diaries we have here are copies and transcripts, rather than the original books (which remain with his family.) The papers in the collection were assembled by Charles’ cousin Robert Belgrave while working on a biography of ‘The Adviser’ that sadly remained unfinished when Robert died in 1991. In addition to the printed versions of the diaries which Robert had transcribed and typed, the collection includes original letters and documents, artwork by Charles Belgrave, printed material on Bahrain, copies of numerous official documents and presscuttings, as well as Robert Belgrave’s early drafts and working papers for the biography.

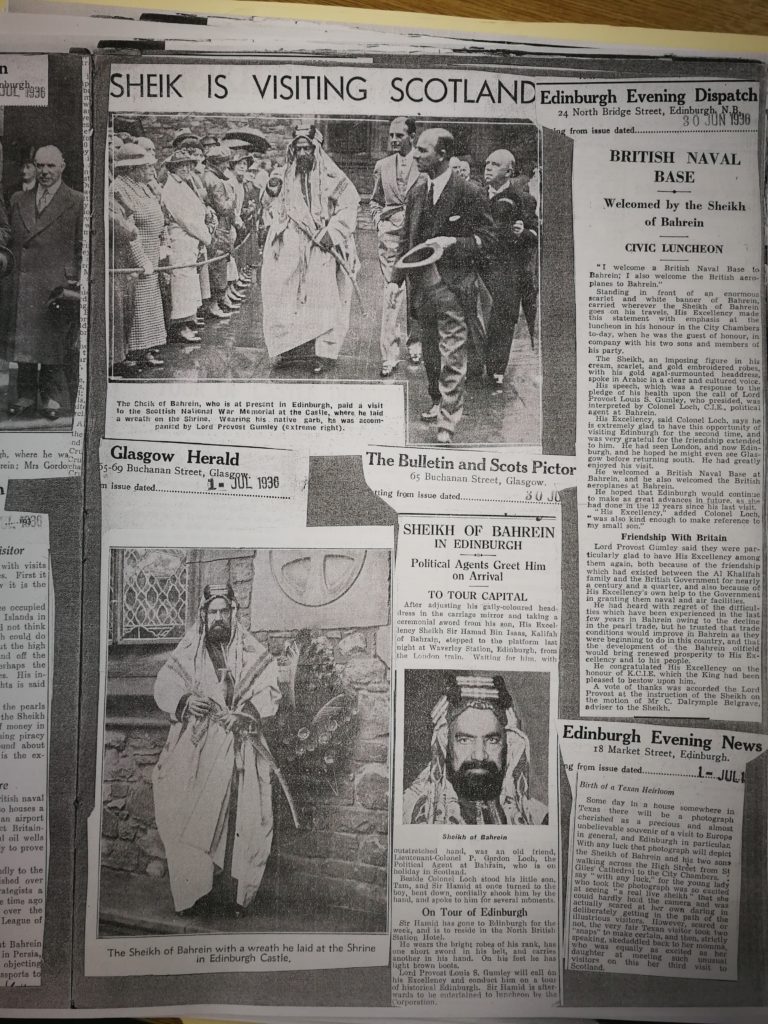

Copies from a large album of presscuttings chronicling the visit of Sheikh Hamed Bin Isa Al Khalifa, to the UK in June 1936. EUL MS 148/2/2/5

During the cataloguing process I read through Belgrave’s diaries from his arrival in 1926 to the final months of 1956 when his departure was imminent, and was struck by the extent of the changes that took place both in Bahrain and in Belgrave himself. In addition to his duties advising the royal family and steering British policy in the region, he set up the police force, sat in judgement in the law courts, oversaw improvements in the health and education systems on the island and played a key role in supporting the establishment of the petroleum industry in Bahrain after oil was discovered in the early 1930s. He took a hands-on approach to all these activities, taking part in midnight raids on illicit arak stills, interrogating prisoners in the police cells, interviewing applicants for various posts on the island and generally involving himself in the minutiae of everyday life in Bahrain. His personal influence in the region was so extensive that he was referred to not only as المستشار (‘the Adviser’) but also as رئيس الخليج (‘Chief of the Gulf’).

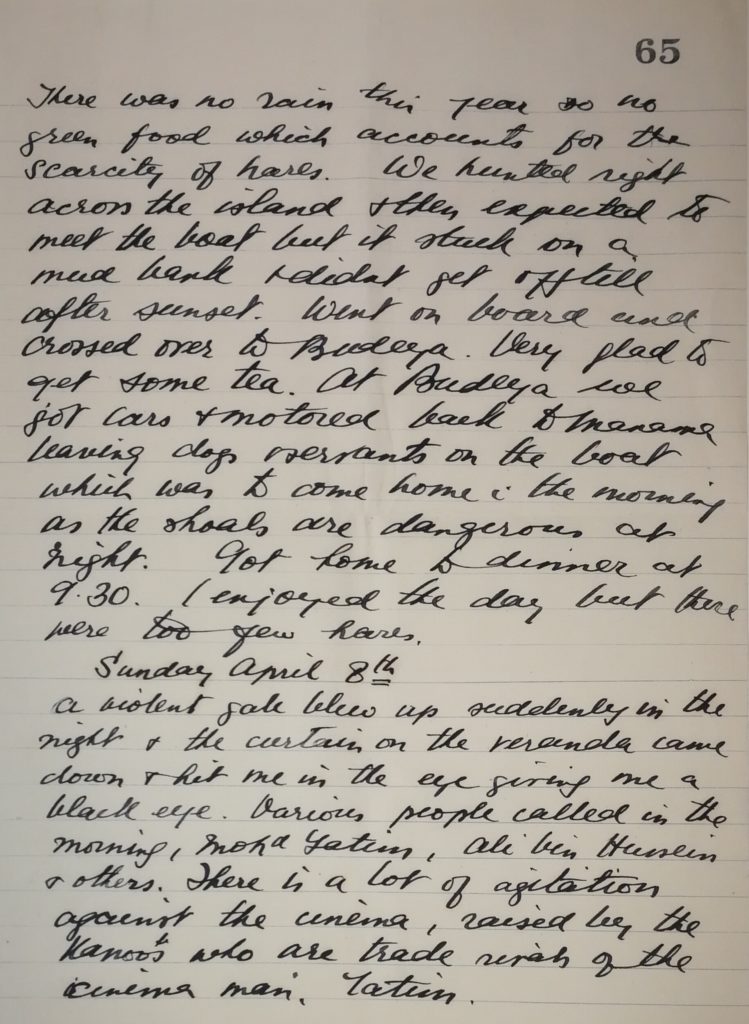

An original page from Belgrave’s diary for 7-8 April 1928 EUL MS 148/2/2/6/4

Despite Belgrave’s heavy workload he was able to make time for leisure activities including playing bridge, reading novels and listening to gramophone records. At times the references to dull dinners, ‘awful people’ and ‘ghastly’ cocktail parties suggest that the constant round of social engagements – integral to his job – could grow tedious. One form of entertainment that does begin to appear more and more regularly in his diary as the years progress is the cinema, which is referred to at the foot of the above letter. Belgrave was able to watch films at a number of different venues, including home movies at the Residency, onboard visiting naval ships and a small theatre in the oil workers’ camp as well as the commercial cinemas that were later established in Manama. Belgrave’s records of how these cinema venues developed provides a fascinating reflection of the changing society in Bahrain, and may be the subject of another blogpost.

Bahrain’s transformation from a small island economy dependent upon pearl fishing into a modern society owes much to Belgrave, who not only managed the island’s administration and controlled its budget, but also took a personal interest in raising standards of education and health, training the police force, establishing hospitals, improving roads and drainage. However, by holding so much power in his own hands and closely aligning Bahrain’s ruling family with British political interests, he made himself a target for the growing nationalist ferment which manifested itself in a series of demonstrations, several of which turned violent and involved the burning of cars and buildings.

These events, and Belgrave’s response to them, are recorded in detail in his diaries, alongside his concerns about intrigue involving Persia and Egypt, and his personal frustration not only with the Foreign Office but also the attitudes of some of the Political Residents – over a dozen of whom came and went during his time there. It is instructive to compare his analysis of political events in Bahrain with the (often critical) confidential reports (EUL MS 148/2/1/3 and MS 148/2/1/5) written by British and American officials – a picture that could be further fleshed out by consulting the views of his opponents, as published in local newspapers and tracts, and the openly hostile opinions of his role found in the Egyptian and Iranian media. Another perspective on the rise of nationalism and the decline of British influence in the Middle East can be traced through the papers of Sir William Luce, who arrived in Bahrain as Political Resident in 1961, four years after Belgrave’s departure, and was instrumental in Bahrain becoming an independent state in 1971. In his diaries for 1956, Belgrave notes the appointment of a new Governor in Aden (Luce) and comments on the troubles there, which in many ways echoed the unrest in Bahrain at the time.

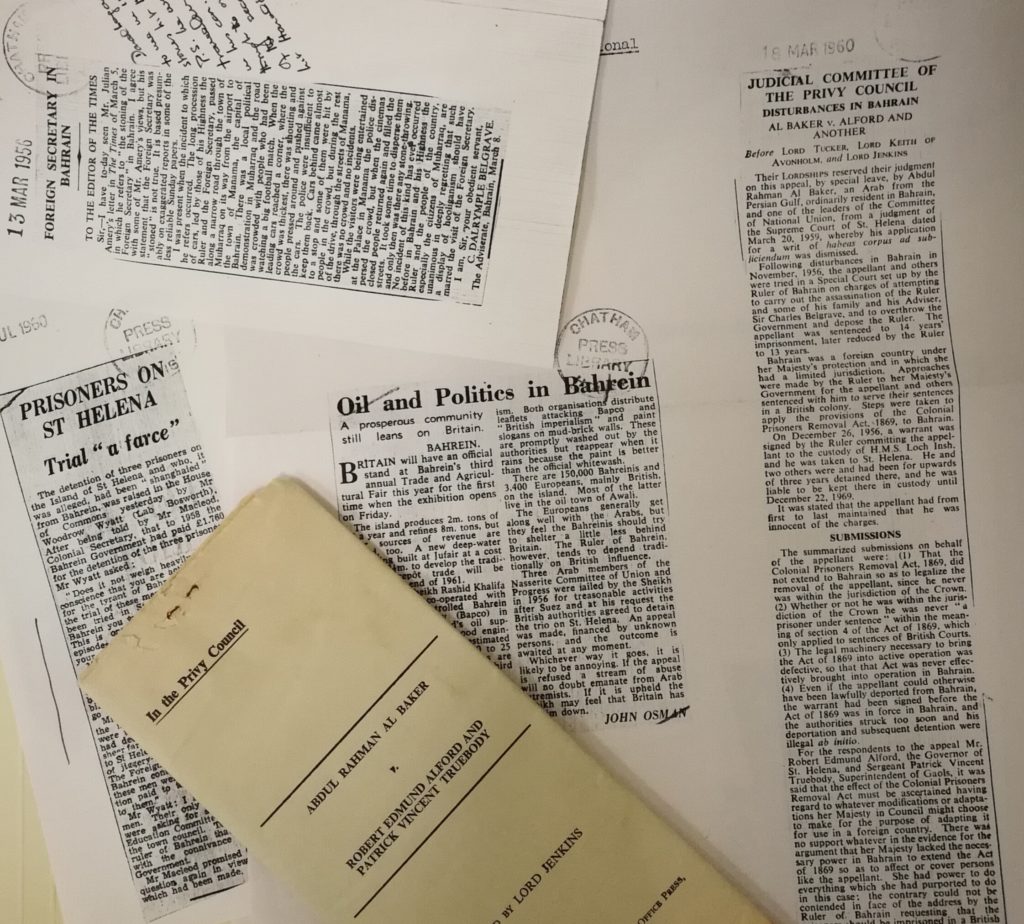

Documents and presscuttings relating to the trial of Abdul-Rahman Al-Bakir, Abdul-Aziz Al-Shamlan and others. EUL MS 148/2/1/7 and 8.

The nationalist movement in Bahrain was led by a small group of individuals who called themselves the Higher Executive Committee, (later the National Union Committee), and made Belgrave’s life increasingly difficult in later years. In November 1956 he had the leaders arrested following a number of deaths and injuries during riots that he claimed had been instigated by the Committee. The trial and conviction that followed caused controversy both in Bahrain and the UK – these events are documented at length in various materials that can be studied in the collection.

Although Bahrain never formed part of the British Empire, during the nineteenth century the ruling Al Khalifa family entered into a series of legal treaties that offered Britain a degree of control over defence and foreign relations in exchange for military and naval protection from pirates and hostile neighbours. As a British Protectorate, Bahrain was nominally independent but effectively supervised by British government officials. Control was exercised by means both subtle and unsubtle, and when the erratic behaviour of the ruler Sheikh Isa ibn Ali Al Khalifa threatened the island’s stability, the British had him deposed in 1923 and replaced with his son Hamed, Belgrave’s employer. After Hamed’s death in 1942 he was succeeded by his son Sheikh Salman, for whom Belgrave continued to advise and govern. Modern readers may find it hard to justify the moral compromises involved in balancing Britain’s vested interests in oil revenues and foreign influence with the authoritarian and feudal nature of Bahrain’s sheikhdom, but the papers in Belgrave’s collection reveal how those engaged in this policy understood their role and perceived the value of their actions.

Demands for ‘The Adviser’ to leave had been circulating for years and were steadfastly resisted by Belgrave, but his position became more and more untenable as the political turmoil in the Middle East during the 1950s was worsened by the disastrous impact of the Suez crisis. There is evidence that the Political Resident, Bernard Burrows, along with the Political Agent Charles Gault and various individuals in the Foreign Office were manoeuvring in the background to have him removed. When Belgrave eventually left Bahrain it was arguably too late, as his refusal to go had only hardened resentment against him as a symbol of British imperialism. In consequence, Bahraini historians – if not exactly airbrushing Belgrave out – tended to minimize the extent of his contribution. While his diaries provide ample evidence of just how much he did for Bahrain, these personal writings also reveal the prejudices and attitudes that were typical of colonial administrators at this period. Those seeking to understand the history of modern Bahrain, the influence of British strategy in the Gulf region, the relationship between Middle Eastern politics and the petroleum industry, or how nationalist movements flourished on regional, national and international levels, would find much of interest by reading Belgrave’s diaries in conjunction with other documents among his papers, as well as other materials in our Middle Eastern collections and the rich resources held next door in AWDU. The catalogue for the papers can be found online here, but please note there are special access requirements for the Belgrave collection.