Jonathan Crusoe was born in Kuwait in 1953 and lived there with his parents until the age of eight when they moved to the village of Goudhurst in Kent. After completing a degree in Arabic and English at Leeds University, he began working as a journalist for the Middle East Economic Digest (MEED) in December 1976. Over the next fifteen years he closely monitored developments in Iraq and Kuwait, as well as Yemen, building up an international reputation as a specialist on the region. On 21 December 1991 he was killed in a car accident near Peterborough at the age of only 38. His working papers were deposited with the University of Exeter as part of a donation from MEED.

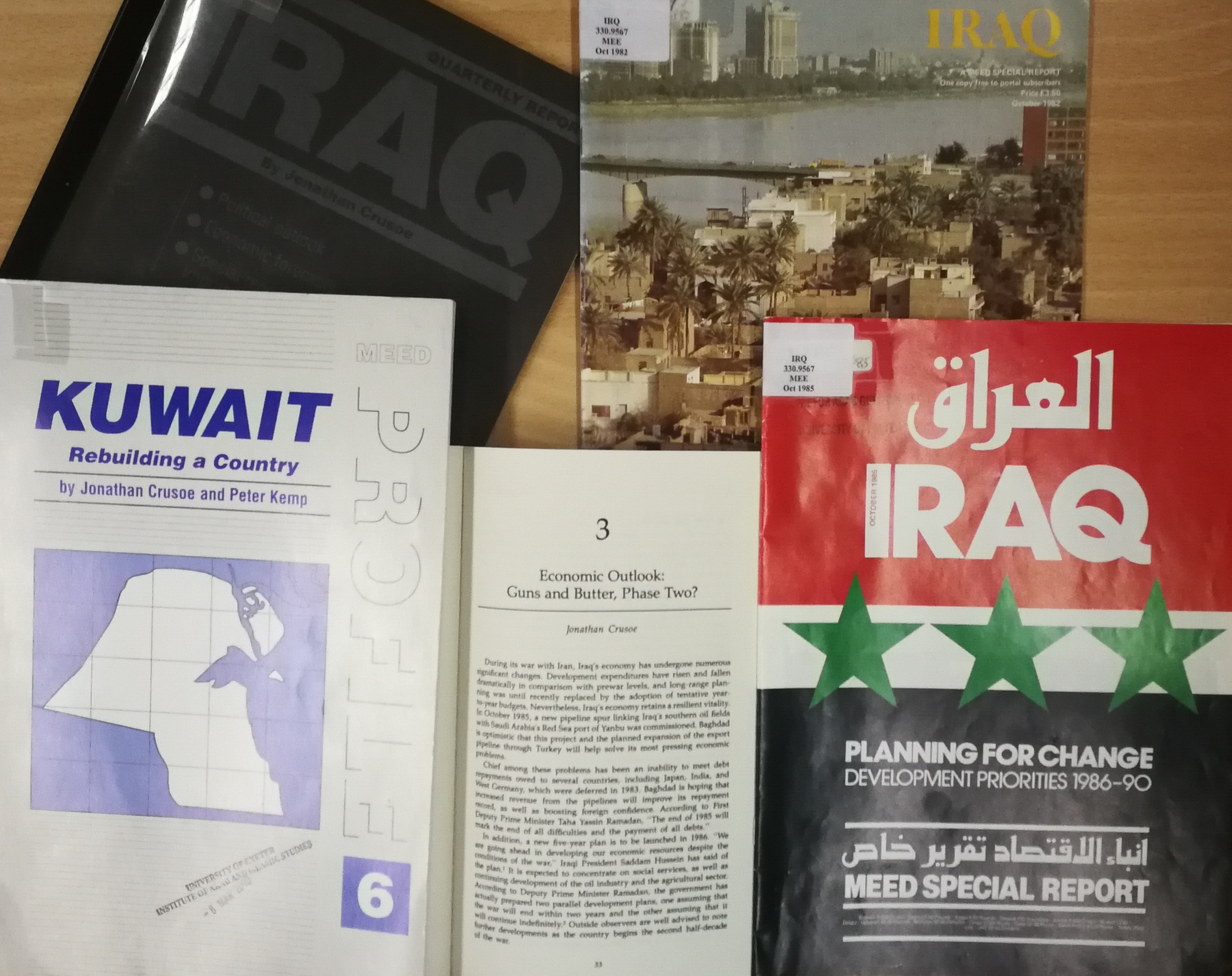

Some of Crusoe’s published work held in the Arab World Documentation Unit (AWDU) in the Old Library at Exeter University

Crusoe’s papers consist primarily of presscuttings, telex press reports, working notes and correspondence (often by fax or telex) on almost every aspect of life in Iraq between 1979 and 1991. There are over 170 folders with the contents arranged thematically in the categories originally assigned to them by Crusoe – topics include: Agriculture, Dams, Archaeology and Architecture, Education, Housing, Power – including Iraq’s nuclear programme – Foreign Relations (with some two dozen individual countries), the Petroleum Industry, Political Opposition groups, Saddam Hussein and his family, Sports, Tourism and Health.

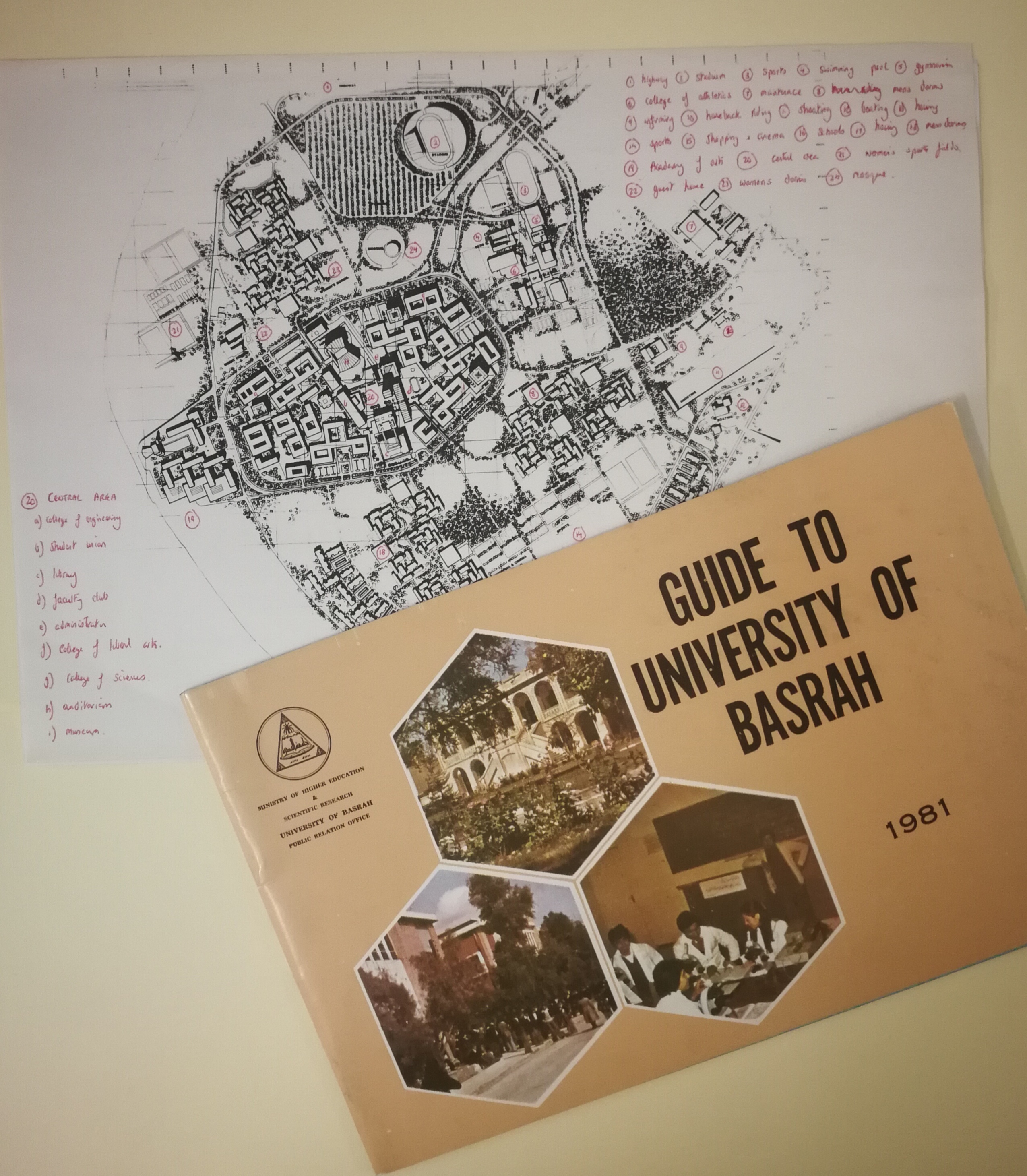

Plans for the new University of Baghdad campus (top) and a 1981 brochure for the University of Basrah (below) – some of the ‘Higher Education’ material compiled by Crusoe. EUL MS 143/8/2

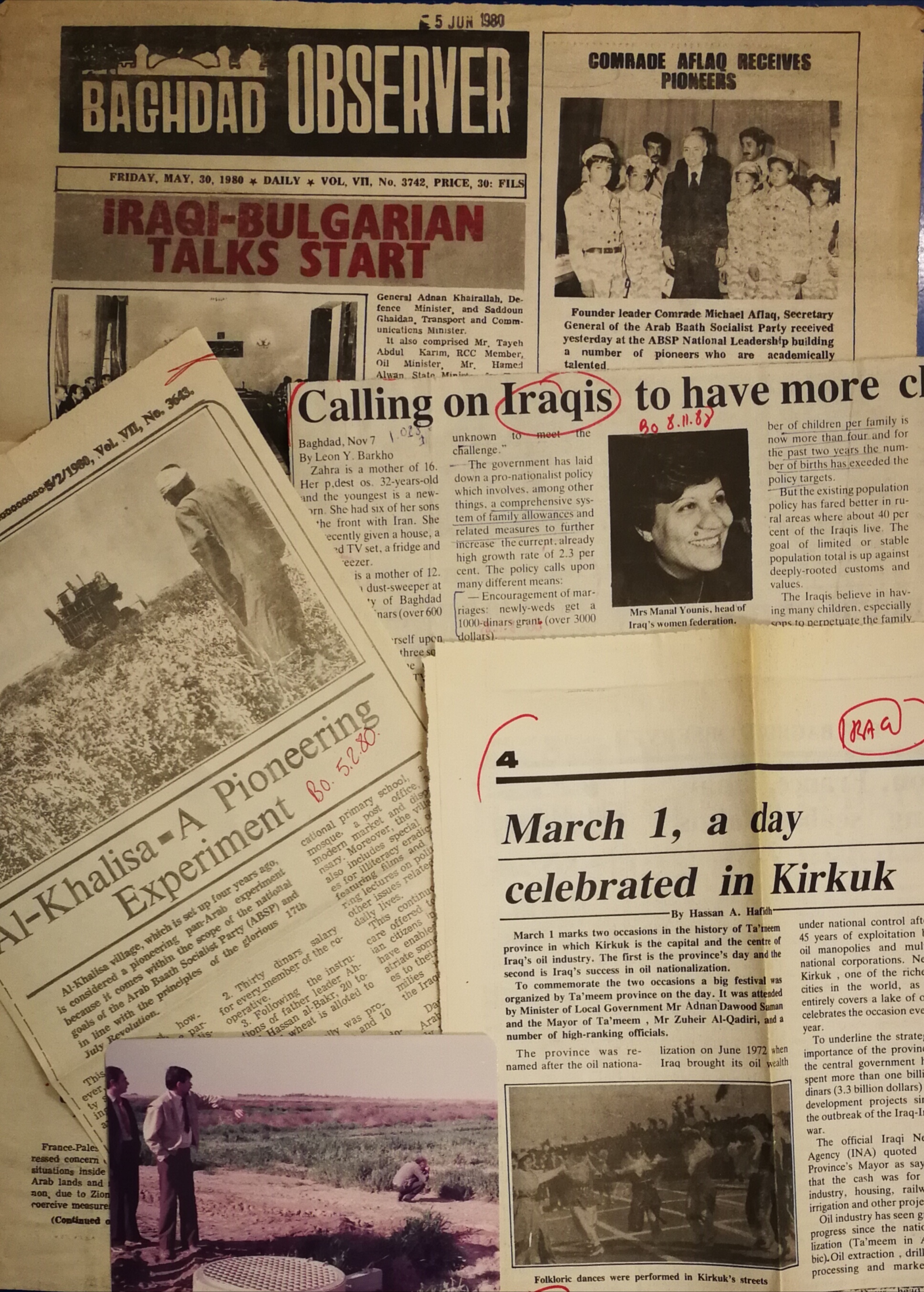

Although many of the presscuttings are from British and American newspapers, there is a wealth of original source material from Iraq, much of which is either unique or hard to find given subsequent events in the region. These include numerous articles extracted from the now-defunct state-run newspaper the Baghdad Observer reporting on everyday life in Iraq, original photographs of Iraqi dams being constructed, advertisements and prospectuses giving details of commercial contracts and building projects, as well as Crusoe’s own handwritten notes and annotations of other documents.

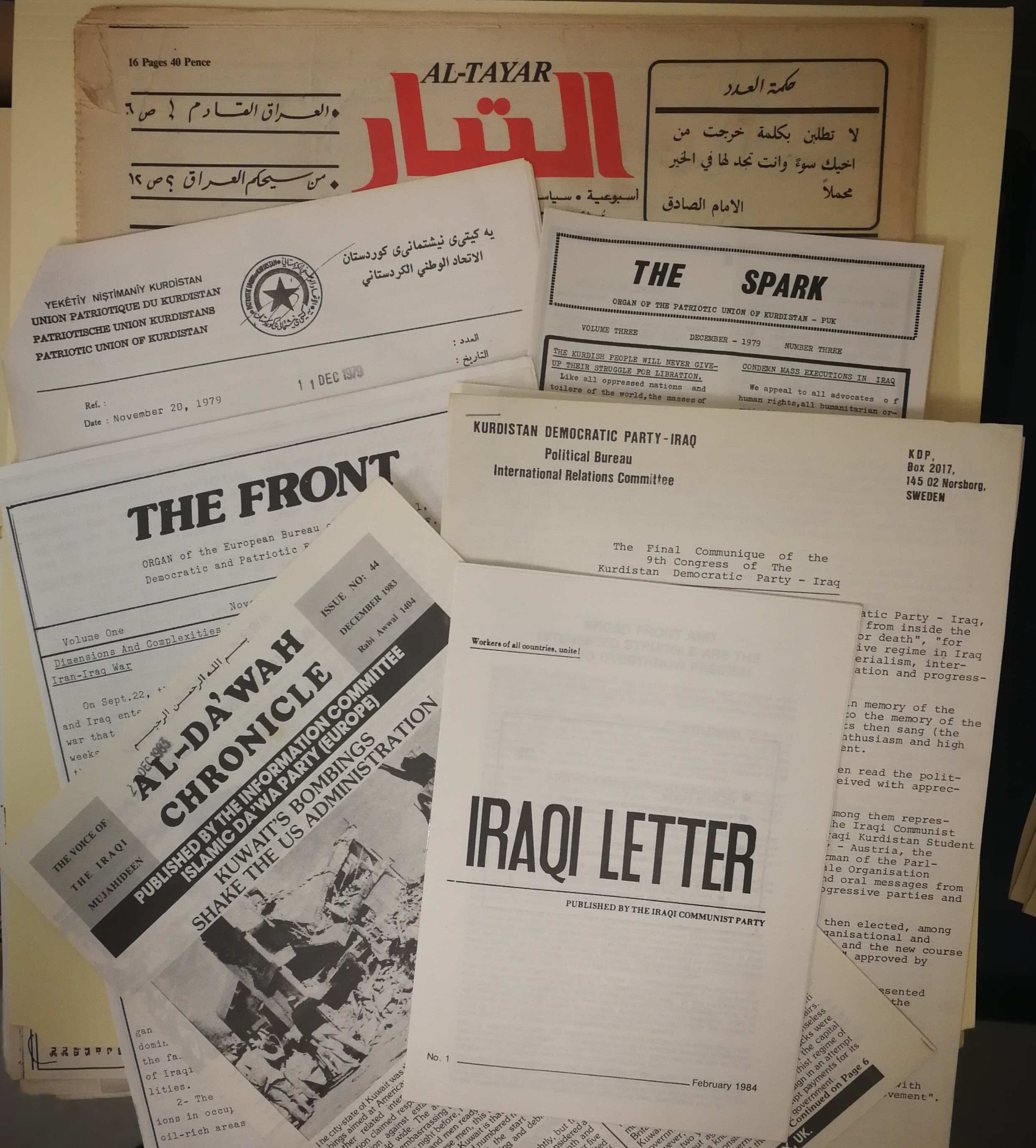

Material on the Kurdish peoples of Iraq, Turkey and Iran is found in dedicated folders as well as elsewhere in the collection, including press releases and booklets issued by different Kurdish groups during the 1980s.

This selection of publications gives some idea of the diverse groups operating (mostly in exile) to oppose the Ba’athist regime of Saddam Hussein. EUL MS 143/14/2/1

Crusoe’s death shortly after the war that followed Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait meant that he never saw the later conflict and US occupation of the region. There are six folders of material covering what he termed – following standard usage at the time – the First Gulf War, between Iran and Iraq (1980-88), and a much more extensive collection of over thirty folders covering the Second Gulf War (1990-91) which covers the conflict chronologically as well as under topics such as sanctions, conditions in Iraq during the war, the oil embargo, burning of oil wells, hostages, media reporting, food and medicine shortages, and postwar reconstruction.

A photograph – probably of Basra – taken during the First Gulf War (1980-88) between Iran and Iraq: note the sandbags on the right, a protection against air and missle strikes. EUL MS 143/19/7

Although Crusoe did much of his work from the offices of MEED in London he also visited Iraq and Kuwait – among the collection of hotel and restaurant brochures is his room card for the Hotel Meridien in Baghdad, where he stayed in 1982. Other material was obtained through his contacts with other journalists, contractors and personal sources in the region, and the archive contains a large amount of telex or fax correspondence through which he gained detailed information on business contracts, construction projects and economic statistics. All this was recorded in his meticulously neat and miniscule handwriting, and it was by carefully cross-referencing and filing this research that he was able to build up the encyclopaedic knowledge for which he was renowned.

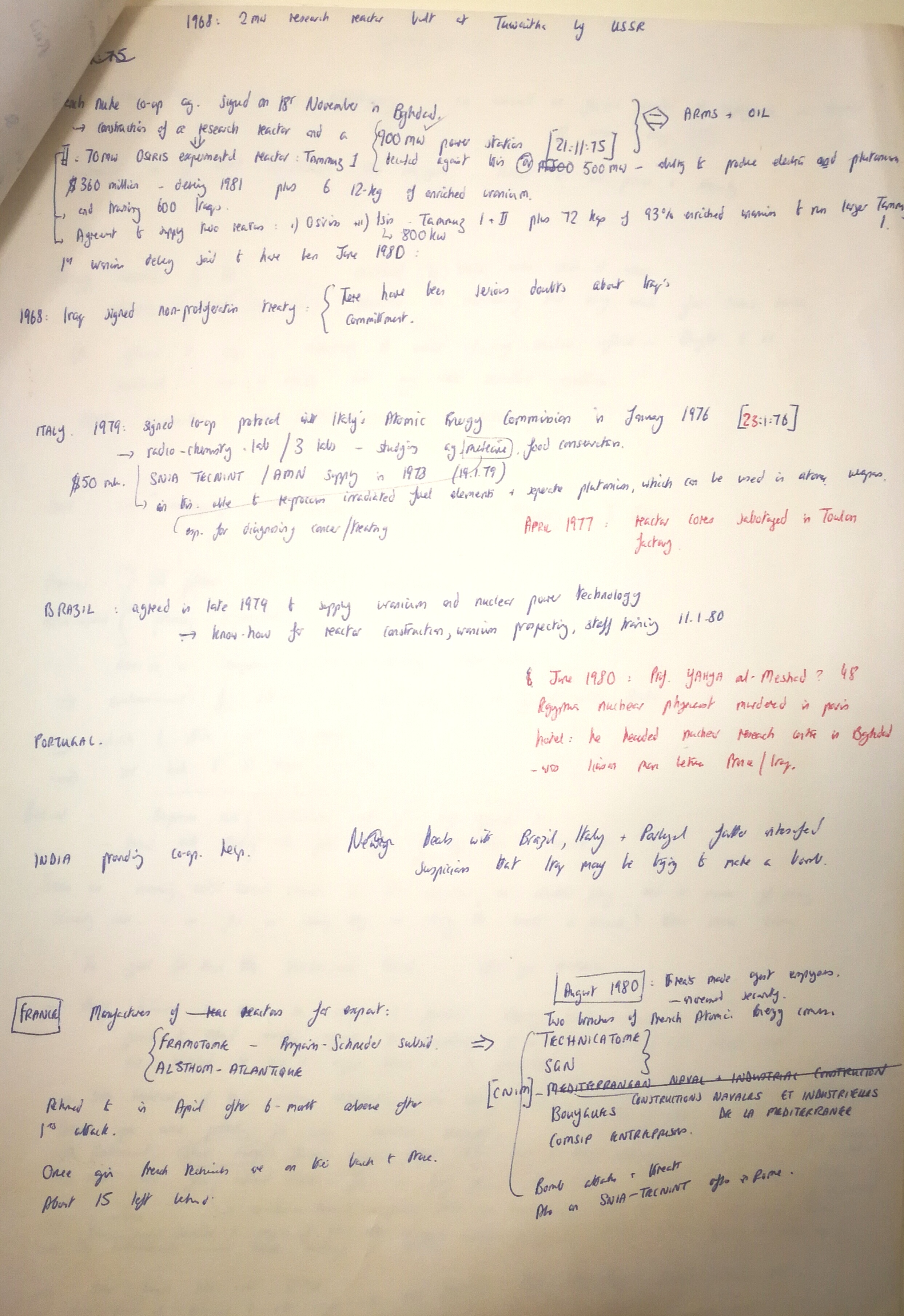

Some of Crusoe’s notes on Iraq’s nuclear programme. EUL MS 143/13/2

Students and researchers interested in the history of the Middle East during the 20th century could find the Crusoe papers a valuable resource for learning about life in Iraq or understanding topics such as agricultural practices, the extent of foreign investment in Iraqi infrastructure under Saddam Hussein, or how information is compiled and presented by conflicting media interests. Despite its strong pro-government bias, the extensive illustrated coverage of everyday life in Iraq found in the Baghdad Observer could be helpful for those interested in understanding how local and international affairs (such as relations with Iran and Syria) were reported to and perceived by the Iraqi people, as well as opening a window on – for example – social conditions or agricultural practices that are often hidden, or the ways in which cultural and political agendas underpinned architectural design projects such as the hotel below.

A photograph of the Hotel Nineveh Oberoi, on the banks of the River Tigris in Mosul. EUL MS 143/19/6. It was later captured by Islamic State militants, who used it as a base from 2014 until its recapture by Iraqi forces in January 2017. Its present ruinous state contrasts sharply with the sense of luxury conveyed by material in the Crusoe papers.

The Hotel Nineveh Oberoi was opened in 1986 during celebrations marking the anniversary of the July Revolution that brought the Ba’athist party to power in 1968. Eleven storeys high and comprising almost 300 rooms and suites with additional bars, restaurants and leisure facilities, its unusual and striking design was intended to evoke the structure of ancient ziggurats such as the one preserved at Ur in southern Iraq. This was part of a wider campaign by Saddam Hussein to draw parallels between the glories of the ancient Babylonian past and his own regime – evidence for which can also be found in the archive materials relating to the ‘International Babylon Festival’ (EUL MS 143/5/2) and Saddam’s restoration of Nebuchadnezzar’s palace. There are other presscuttings about the new hotel during the 1980s and a letter from an Indian journalist to Crusoe, pointing out that the Indian construction company Oberoi had incorporated traditional features of Indian architecture into the design.

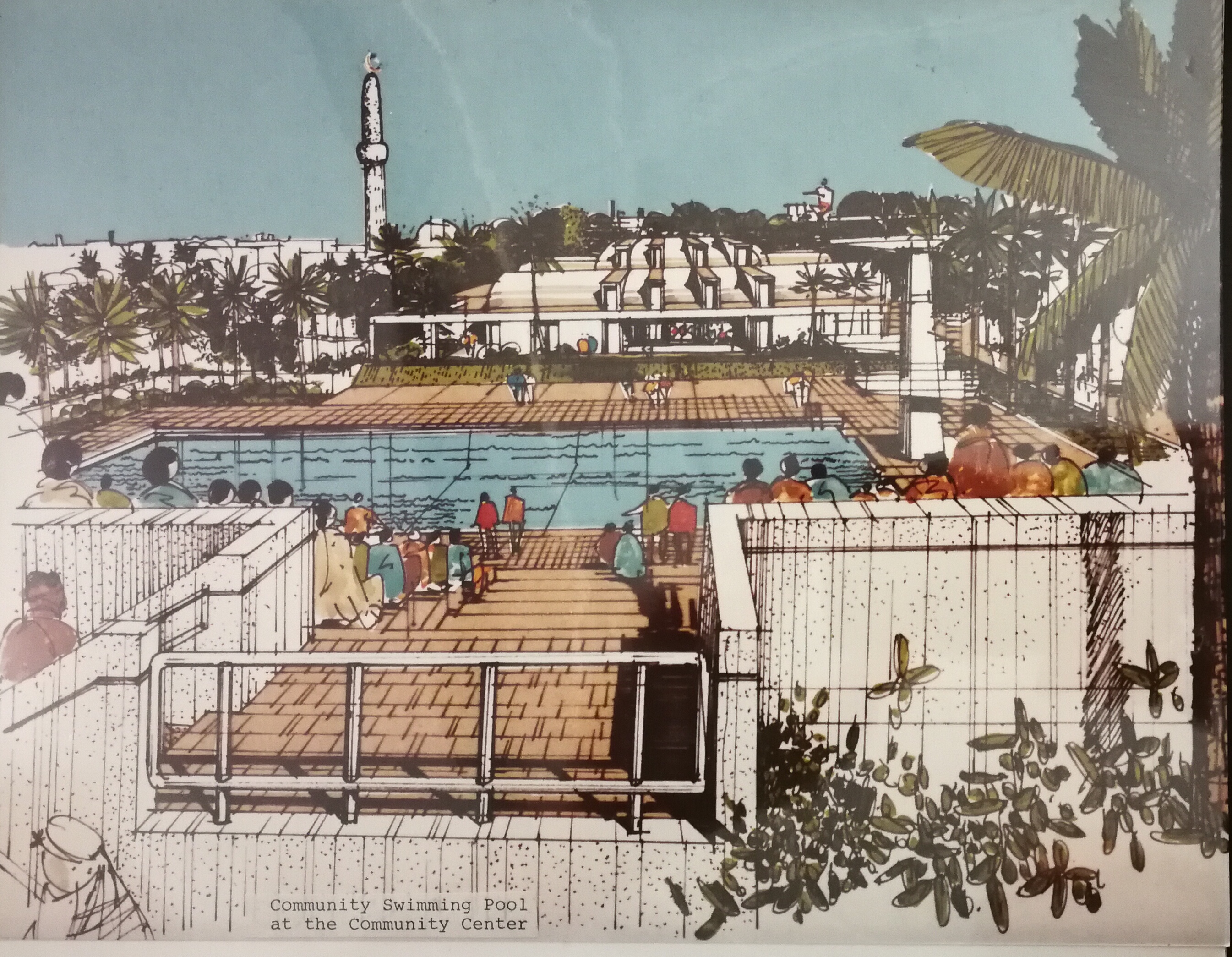

Designs produced by the Architects Collaborative for a community project ca. 1981. EUL MS 143/4/1

Crusoe collected information on such projects at every stage, amassing hundreds of adverts from the Baghdad Observer in which the Iraqi government sought contractors for infrastructure schemes and building works. He also compiled lists of foreign contractors, with contact details, notes on personnel, financial records, trade prospectuses, commercial bids, architectural plans and annual reports. Working within the Crusoe archive it is possible to study these items within a wider framework of material on the political, cultural and economic context; users of the archive could augment their research using the resources in AWDU, such as official reports, documentation, statistical records and presscuttings, as well as an extensive run of MEED and similar publications. Those interested in the history of journalism and media studies can trace the process by which raw material from original sources evolved into published reports by making a close comparison of Crusoe’s notes and correspondence with Reuters press messages, draft typescripts and the final text that appeared in MEED and other publications. There is also a 58-page typed document compiled by a senior staff writer at MEED, entitled ‘Sources of Construction Information and their Use in Construction Reporting by MEED Writers’, which examines in detail how different members of the journalists’ team obtained, used and verified their sources.

Anyone wishing to use the Jonathan Crusoe archive should contact Special Collections. The catalogue can be consulted here.

Further Reading

Obituaries of Crusoe were published in The Independent on 30 December 1991 (p.17) and the Middle East Economic Digest (MEED), 10 January 1992 (p.15).

Jonathan Crusoe’s published work includes

MEED Special Report: Iraq.

London: MEED, 1985

‘Economic outlook: guns and butter, phase two?’, in Frederick W. Axelgard (ed.), Iraq in transition: a political, economic and strategic perspective.

Washington: Georgetown University, 1986.

MEED Profile: Iraq

London: MEED, 1989

MEED Quarterly Report: Iraq

London: MEED, 1990

Kuwait: rebuilding a country (with Peter Kemp)

London: MEED, 1989