Although the archives of John Shebbeare and John Craven Wilkinson (1934-) both relate to Oman, they are very different in both size and scope. Wilkinson is arguably the foremost Western scholar to have worked on the history of Oman, a field of study that he has dominated for the last half century. As his collection of papers is substantially a record of this distinguished career, it will be helpful to offer a summary of Wilkinson’s life and work.

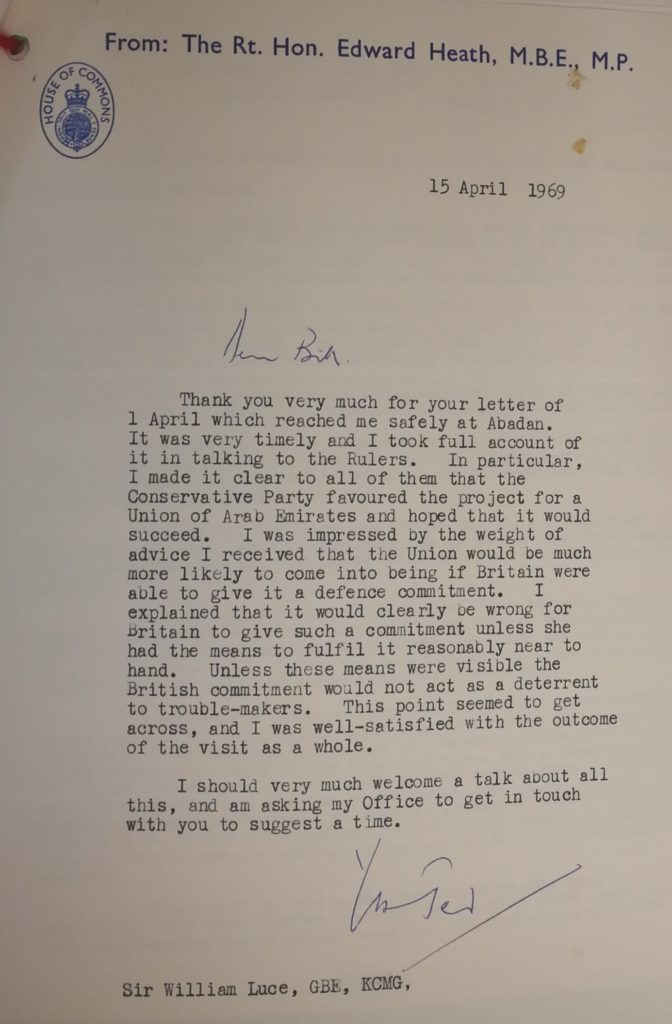

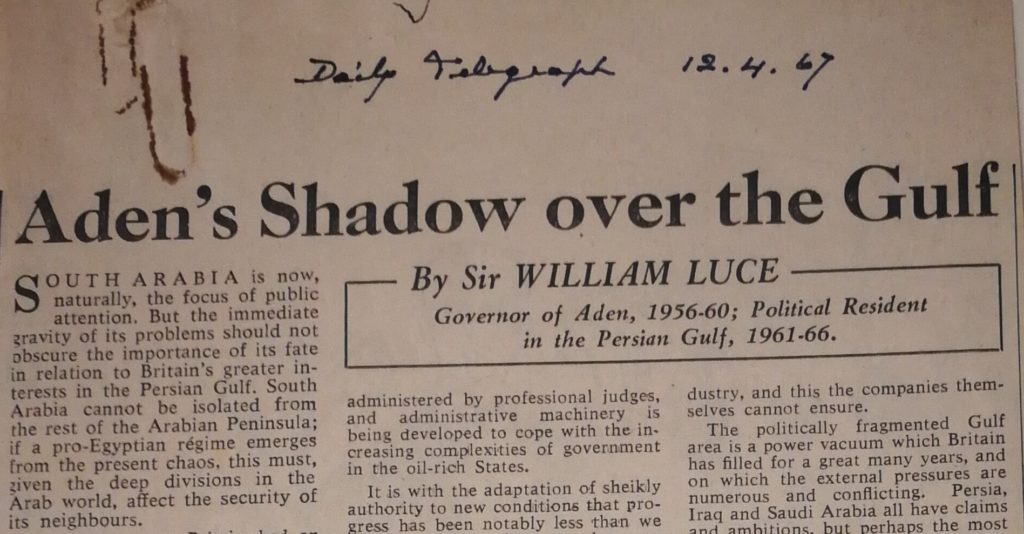

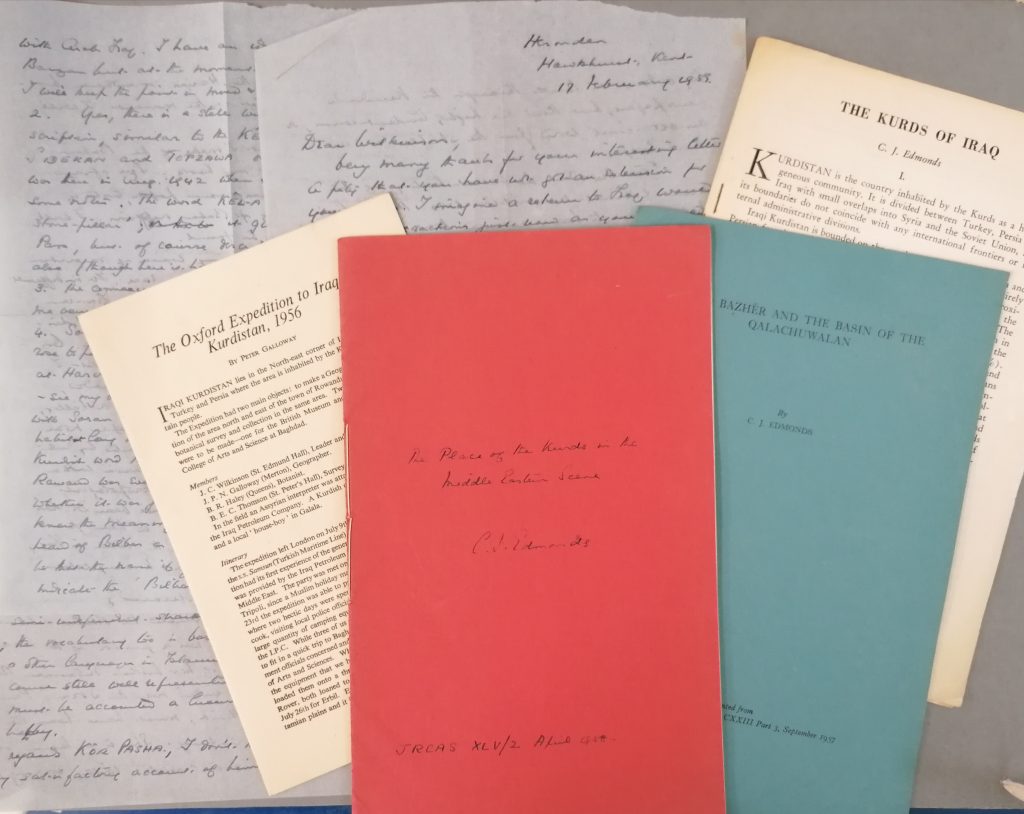

Born in 1934, he was educated at Harrow before going up to Oxford where he matriculated at St Edmund’s Hall in 1955. While still a student, he led a university expedition to NE Kurdistan in 1956 that involved climbing Halguard – the highest mountain in Iraq – and a walk of some 600 miles through the mountainous regions to the north east of Rowanduz as far as the borders with Turkey and Iran. Papers relating to this expedition include correspondence with Cecil J. Edmonds (1889-1979), a former political officer in Kurdistan who was an expert authority on the area and was then Lecturer in Kurdish at SOAS. (EUL MS 119/1/1/1 and 119/3/1).

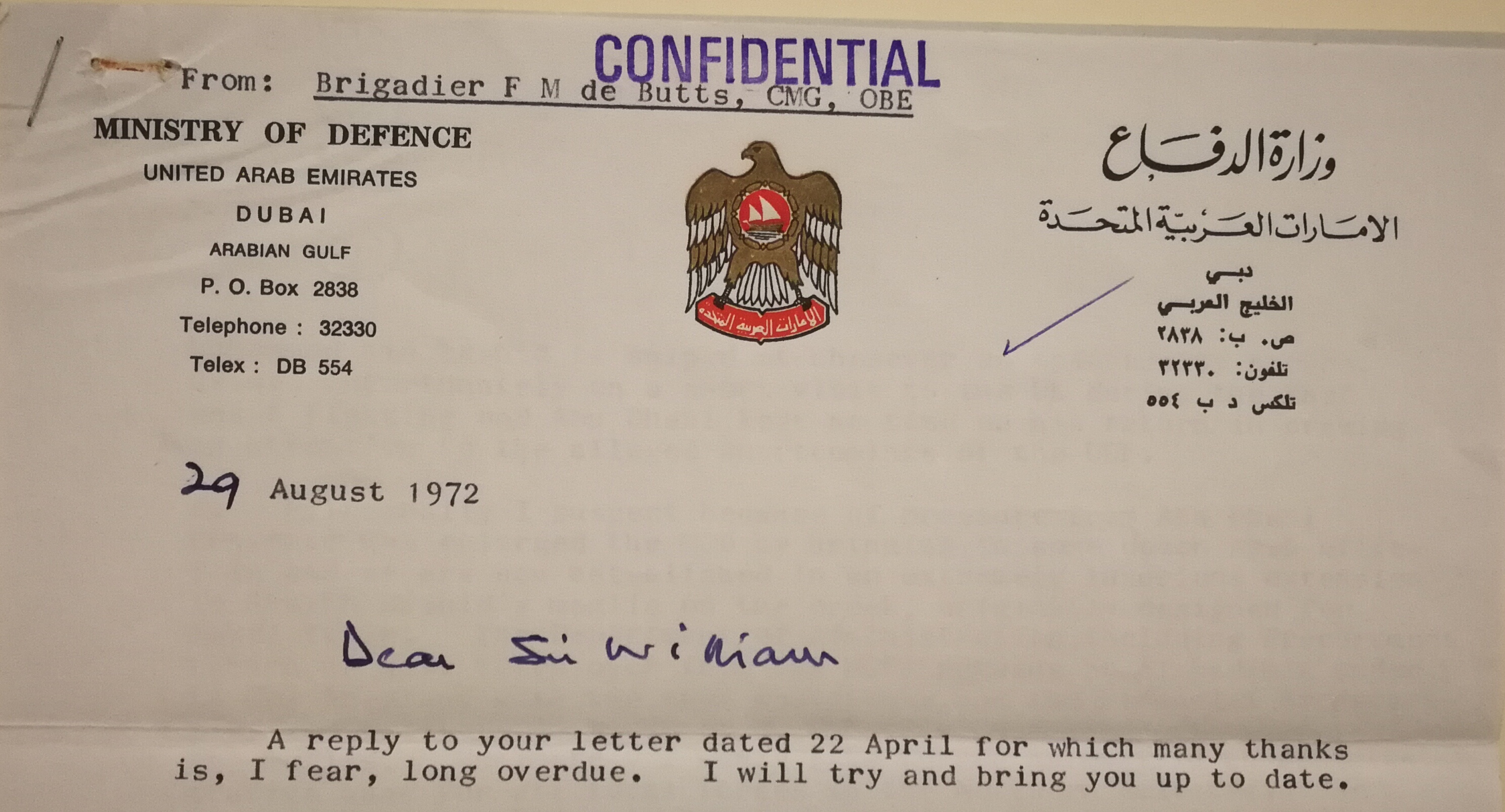

Correspondence and papers by C.J. Edmonds relating to Wilkinson’s 1956 expedition to Kurdistan

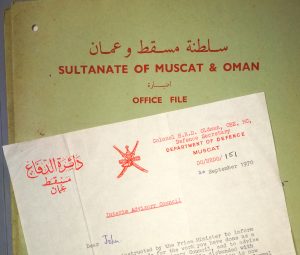

In his published account [‘Oxford university expedition to Iraqi Kurdistan, 1956’, Journal of The Royal Central Asian Society Vol.45:1 (1958) pp.58-64] Wilkinson paid tribute to the assistance provided by the Iraq Petroleum Company (IPC), who supplied a guide and a landrover as well as other forms of support, and after graduating from Oxford in 1957 he went to work in the oil industry. The Sultan of Muscat and Oman had granted a 75-year concession to the IPC, who set up an associate company called Petroleum Development (Oman) to run the oil operations in the Sultanate. Wilkinson was appointed first to Qatar in 1958, moving to Abu Dhabi the following year and then on to Trucial Oman before he transferred to work for Shell in 1962. After working in Laos and other locations, he returned to Oman in 1965. Many of his papers, including correspondence and reports, relate to his work for PDO during this time. (See for example EUL MS 119/2/3/1-4 and correspondence files.)

Oman and the Oil Industry

Petroleum Development Oman brochure, EUL MS 119/2/3/4

During the 1950s and 1960s Wilkinson witnessed first-hand how the politics of oil clashed with the Imamate society that inhabited central Oman – a topic that, in its various ramifications, would remain at the centre of much of his scholarly work over the next few decades. However, in order to understand this fully, it is necessary to explain a little more about Oman itself.

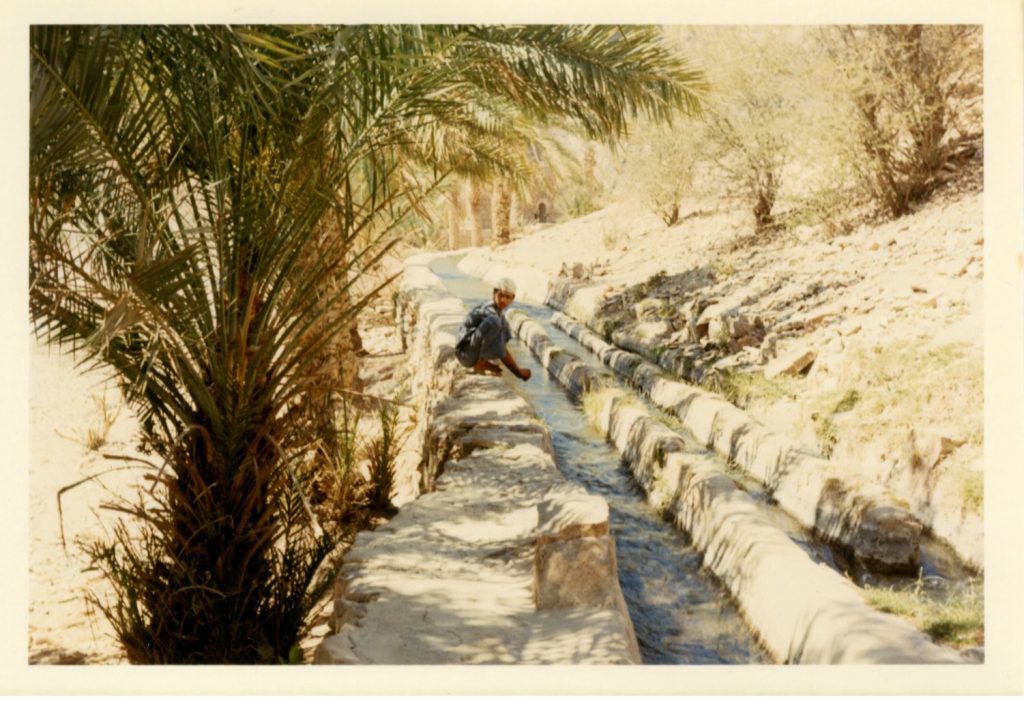

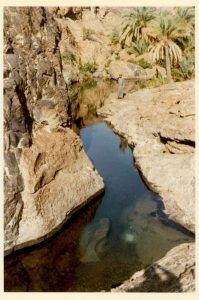

A water channel in Oman, part of the falaj irrigation system, from an official Omani bulletin EUL MS 119/2/2/4

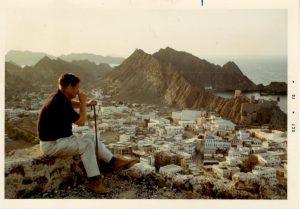

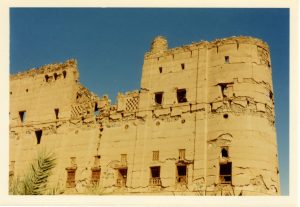

Oman is essentially an island, bordered on two side by the waters of the Gulf of Oman and the Arabian Sea, and on the others by the vast sands of the the Rub’ al Khali desert or ‘Empty Quarter’ that separates Oman from Saudi Arabia, Yemen and the UAE. Furthermore, the country was roughly divided into two separate parts – the outward-looking, secular, seafaring society along the coast which was governed from Muscat, and the closed, more-or-less self-sufficient tribal communities who inhabited the interior region or ‘Oman proper’, who were led by a an elected Imam who followed the tenets of the Ibadi sect of Islam. (This dual nature was reflected by the country being referred to as Sultanate of Muscat and Oman from 1820 until 1970, when the coup (referred to here) simplified the name to just ‘Oman.’) The tribal organisation of the interior was based around the doctrines of Ibadism and the pattern of village settlements that were founded upon the falaj irrigation system, a complex system of channels that distributed water to owners who paid for specific units of time rather than volume of water. In order to penetrate the interior – where the Sultan’s authority was not recognised – the oil companies needed to deal with the Omani tribal leaders, over whom Saudi Arabia claimed a degree of sovereignty. Events in Oman during the mid-20th century are a complex web of rivalries between the British-influenced Sultan and the Saudi-influenced Imam, between the ambition of American oil companies and British diplomatic strategists and between the religious character of the Imamate tribes and the commercial secularism of the maritime coast, much of it muddied by disputes over boundaries that had been drawn up by British diplomats seeking to consolidate their influence in the Gulf region, but which did not correspond with the topographical and cultural realities of the region.

Understanding these complexities was essential for those working in the oil industry, and Wilkinson applied himself carefully to gathering as much information as he could on the region, its history, people and topography, climate, flora and fauna, Arabic etymology, religion and politics. In 1965 he left Shell and returned to Oxford to work on a doctorate under the supervision of Albert Hourani and Freddy Beeston, whose letters are in the archive. The result was a Ph.D thesis with the title Arab settlement in Oman: the origins and development of the tribal pattern and its relationship to the Imamate (1969), a copy of which is held in AWDU.

Abu Dhabi Petroleum Company report EUL MS 119/2/3/5

From 1969 until his retirement in 1997, Wilkinson taught at Oxford University, holding the posts of Lecturer and Reader, as well as Fellow of St Hugh’s College. During this time he consolidated his reputation as an expert on Oman and the Gulf, publishing a stream of important monographs and journal articles on a range of inter-related topics. Many of the papers in the archive formed part of the research materials he gathered for these publications, and include early drafts, conference papers and correspondence with other leading scholars such as Albert Hourani, Bob Serjeant, Freddy Beeston, Dale Eickelman, Calvin Allen, A.K.S. Lambton, Elizabeth Monroe, Ralph Daly and Daniel Varisco. (See for example EUL MS 119/3/14-20).

In order to understand better the nature of this scholarship, a brief overview of some of Wilkinson’s most significant publications may be helpful.

J.C. Wilkinson’s Published Work

Water and Tribal Settlement in South-East Arabia. A study of the Aflāj of Oman (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1977)

Wilkinson’s first major monograph was a remarkable, ground-breaking study of the relationships between water, land, community and religion in Oman. Beginning with an account of the arid climate and topography of the country, Wilkinson proceeds to show the vital importance of the irrigation system known as falaj, how this developed from the earlier Persian qānat system, and how this changed following the arrival of Islam as the tribal society developed under the influence of the Ibadi sect. It is a complex book in which Wilkinson applied his skills as a geographer, historian, linguist and Islamic scholar, and is all the more impressive considering most of his materials were drawn from primary sources and fieldwork. One of his most valuable sources – discussed in detail in Chapter X – was the Malki falaj book, a 19th century manuscript recording patterns of water ownership around the cultivated land around Izki, a village in central Oman.

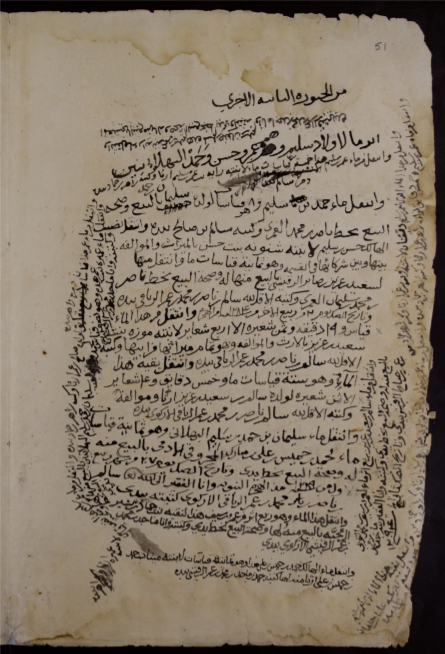

A page from the Falaj Malki manuscript (EUL MS 119/4/1 ) with details of water rights near Izki in the 19th century

The Falaj Al-Malki is divided into seventeen channels that extend over nine miles, distributing to the villages of Al Nazar and Al Yemen and other agricultural areas around Izki. The manuscript has been digitised and can be viewed here.

The Imamate Tradition of Oman (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987)

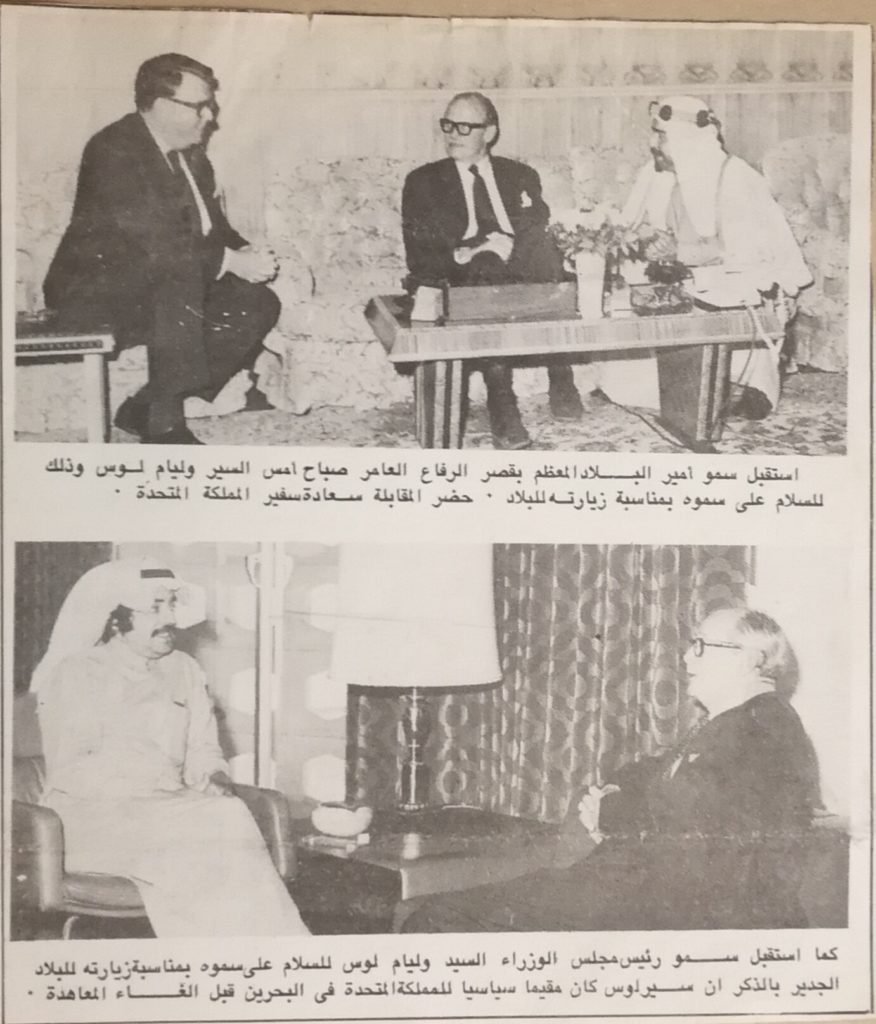

In his introduction to the book, Wilkinson reveals that he intended to write a dramatic account of the rivalry between oil companies caught up in the region’s political struggles, along the lines of Hammond Innes’ novel The Doomed Oasis (1960) – and it is interesting to note that the diaries of Charles Belgrave record Innes’ visit to Bahrain in 1954 to gather background material for his story. As work progressed, however, Wilkinson’s introductory material on the Imamate gradually came to dominate the book and the chapters on the oil industry were pushed to the very end. The Imamate Tradition of Oman covers well over a thousand years of Omani history, exploring the relationship between the Imamate and the tribal system of the interior in terms of a cyclical power dynamic and the tension between centralised authority necessary for statehood and the decentralised nature of the tribal communities, as well as the disastrous consequences of the involvement of foreign powers i.e. Britain. With regard to the latter, Wilkinson’s account of the demise of the Imamate during the 1950s is severe in its criticism of Sultan Said bin Taimur’s rule.

Arabia’s Frontiers. The Story of Britain’s Boundary Drawing in the Desert (London: I.B. Tauris, 1991)

In both the works above Wilkinson discussed Britain’s role in Omani affairs, with reference more widely to efforts by the British government to negotiate boundaries around the Persian Gulf and in Southern Arabia that would protect its sphere of influence. This was a flawed strategy, made worse by the lack of any valid legal framework to support it, that helped give rise to many of the wars and boundary disputes in the region during the 20th century. (Wilkinson’s book was published just after the Second Gulf War, in which Saddam Hussein had justified his invasion of Kuwait on the grounds that it had belonged to Iraq under Ottoman rule, and the British creation of a separate sheikhdom in 1913 was an illegal act of imperialism that had never been ratified.) The book provides a detailed, objective and often sharply critical analysis of British involvement in boundary arbitration, and the legacy this has left for the Gulf. The Wilkinson archive contains numerous boundary maps from the 19th and 20th centuries, while papers relating to the oil concession negotiations provide a first-hand view of how such disputes played out on the ground.

Ibâḍism: Origins and early development in Oman (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010)

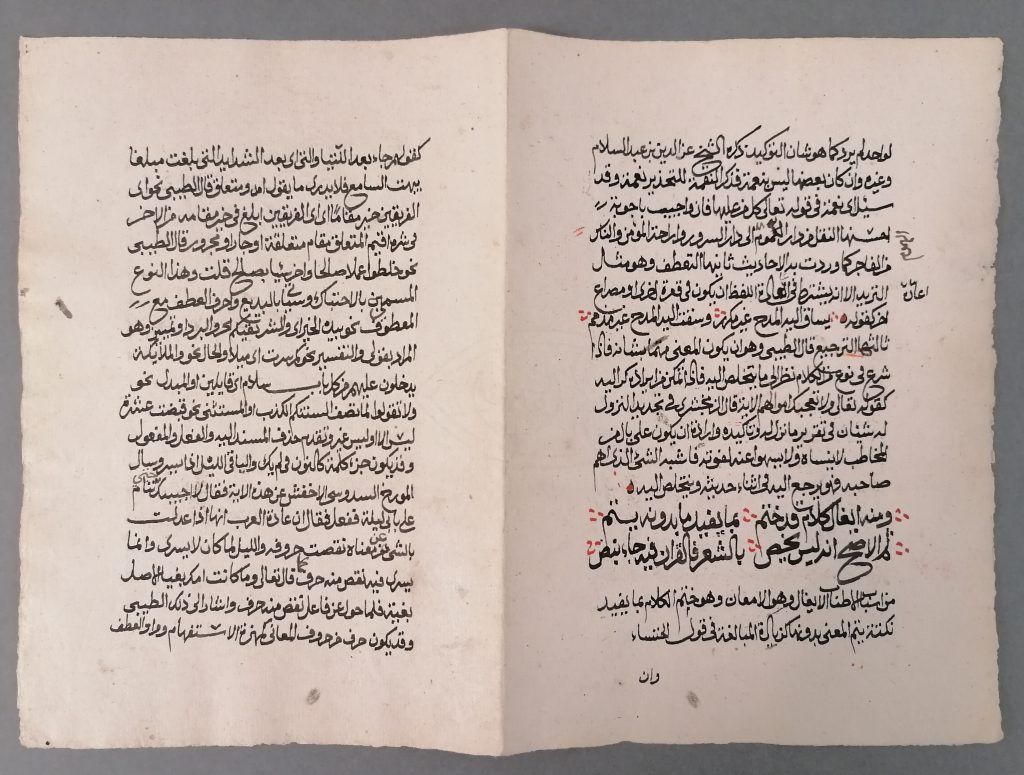

Ibâḍism had been a central element of Wilkinson’s work for over forty years due to its importance in the legal, political and cultural development of Oman, and in this book he revisited some of his earlier research in the light of new sources such as the Kitab ansab al-‘Arab (and other manuscripts made available in the library of the Ministry of National Heritage and Culture following the 1970 change of regime) as well as some of the recent scholarly work done on the history of Ibâḍism since his earlier publications. Dense and detailed, Wilkinson’s Ibâdism uses his encyclopaedic knowledge of the historical framework of the Imamate and Oman to reassess the early origins of Ibâdism during the first six centuries of Islam, beginning in Iraq with the early Ibâdi movement in Basra and tracing its development against a background of tribal migration and settlement through to the twelfth century. The progress of Wilkinson’s thinking on Ibâḍism can be seen in some of his published works on the topic (EUL MS 119/1/1/4) as well as the sources he used, such as the manuscripts EUL MS 119/4/14 and EUL MS 119/4/17. Almost all of Wilkinson’s studies were based at least in part upon careful study of Arabic manuscripts, some from the late medieval period, and his archive contains both original manuscripts and copies in various media forms.

A bifolium legal document in black and red ink, with some marginal annotations (EUL MS 119/3/23)

The Arabs and the Scramble for Africa (Bristol, CT: Equinox Publishing, 2015)

Although much of Wilkinson’s research focused on the interior of Oman, on p.332 of The Imamate Tradition (1987) he mentioned that his ‘current research interests’ were being directed towards the study of Omanis in the Congo, and almost thirty years later the fruit of the research was published. This book charts the involvement of Omani Arabs in East and Central Africa over several centuries, while concentrating on the period between 1820 and 1890 with the demise of the Sultanate of Zanzibar, which had belonged to a branch of the Omani Al Said dynasty since 1698. Utilising a huge range of archival sources as well as half a century’s accumulated knowledge of Omani history and documentation, Wilkinson also drew on his geographical background to emphasise the importance of land, sea, weather and climate in the decisions made by the Omani colonisers of Tanzania, Kenya, Mozambique and the Congo. Among his papers is an annotated 12-page typescript copy of a 1932 article, ‘The Al Bu Said dynasty in Arabia and East Africa’, translated into English [possibly by Wilkinson] from the German of Rudolph Said-Ruete, the son of Emily Ruete (born Salama bint Said), author of Memoirs of an Arabian Princess from Zanzibar (EUL MS 119/1/2/12).

A small selection of Wilkinson’s published work (EUL MS 119/1/4)

Even this brief overview of five major monographs – quite apart from the numerous journal articles and conference papers he has written – will convey a sense of Wilkinson’s erudition across a wide range of interdisciplinary scholarly fields. The papers in this archive provide a rich resource for researchers interested in topics as diverse as the history of Oman, the Persian Gulf, the Indian Ocean and East Africa, the petroleum industry, hydrology, irrigation and agriculture, Ibâdism and the early history of Islam, tribal systems, archaeology, kinship and Islamic law, Arabic manuscripts, geology, maritime history and the flora and fauna of the Middle East. As Professor Wilkinson is still working and writing, permission needs to be sought for access to some of the papers, but the catalogue entries for the Wilkinson archive can be examined here and further enquiries can be directed as usual to the Special Collections department.