The papers of John Digby Shebbeare (1919-2004) are one of the smaller collections in the Middle East Archives, comprising just two small files, a photograph album and an envelope of newspaper cuttings, but they nonetheless provide a unique perspective of Oman’s landscape, both in its political and geographical senses.

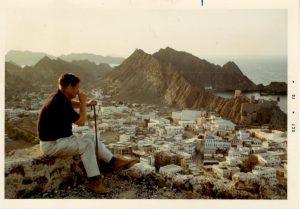

John Shebbeare overlooking the old town of Muscat

John Shebbeare was born in Oxfordshire, one of three sons of the Rev. Charles John Shebbeare, who was Rector of Swerford and later chaplain to King George V. John was educated at Aysgarth Preparatory School, Yorkshire, Highfield Preparatory School in Hampshire and Rugby College. Following training at the Royal Military College, Sandhurst, he obtained a commission in the Indian Army in 1939 and saw service in India, Egypt, Persia and Iraq, serving with the Poona Horse and eventually attaining the rank of Lieutenant Colonel. His older brother Bill was killed in France in 1944. After retiring from the army in 1948, he was admitted to Lincoln’s Inn and was called to the Bar in 1951. He practised as a lawyer firstly in the family chambers in London and then as a legal advisor in the Department of Health. However, having spent so many years in the Middle East, he was keen to return to the region and secured a job in Baghdad as legal adviser to the consulting water engineers Binnie, Deacon & Gourley.

After spending five or six years in Baghdad, Shebbeare studied Arabic at Shemlan in the Lebanon, then moved to a post as District Resident in Beihan in the Aden Protectorate, (now in Yemen.) When the British withdrew from Aden in 1967 he had no wish to leave the Middle East and contacted Said bin Taimur, the Sultan of Muscat and Oman. Following an interview with the Sultan at Salalah, he was offered – and accepted – the post of ‘Secretary in Internal Affairs’. This was an advisory role in which Shebbeare was meant to guide the Sultan on internal affairs as well as using his legal training to monitor the activities of Oman’s wālis [governors] and qādis [religious judges].

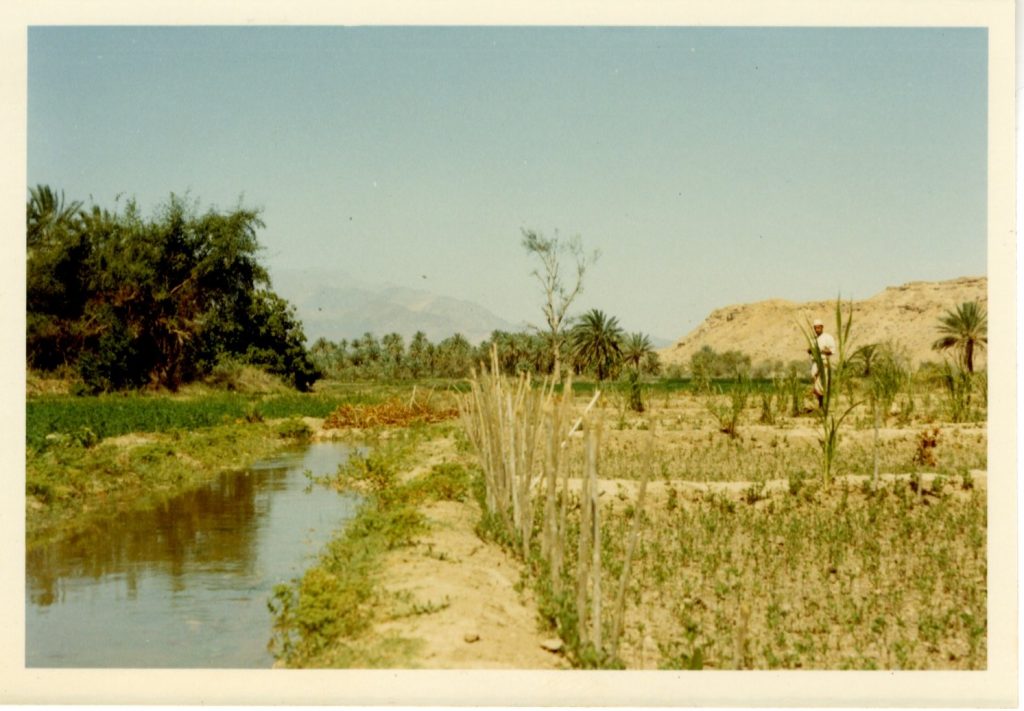

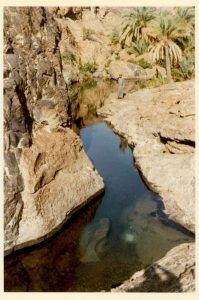

One of John Shebbeare’s many photographs of the Omani falaj system

Oman is a dry and arid country with very low annual rainfall – hence the importance of the irrigation system known as ‘falaj’ أَفْ (plural أَفْلَاج aflāj). In classical Arabic, the word أَفْ has nothing to do with water, but refers to the distribution of shares, and as Shebbeare explains in some of his lecture notes (EUL MS 293/1), these are measured in units of time rather than volume. Usually the falaj is owned collectively, with water flowing out from the main channel into individual gardens, for which each landowner buys the right to so many minutes, or hours, per day or week. A nineteenth century document listing the owners of a falaj can be viewed here.

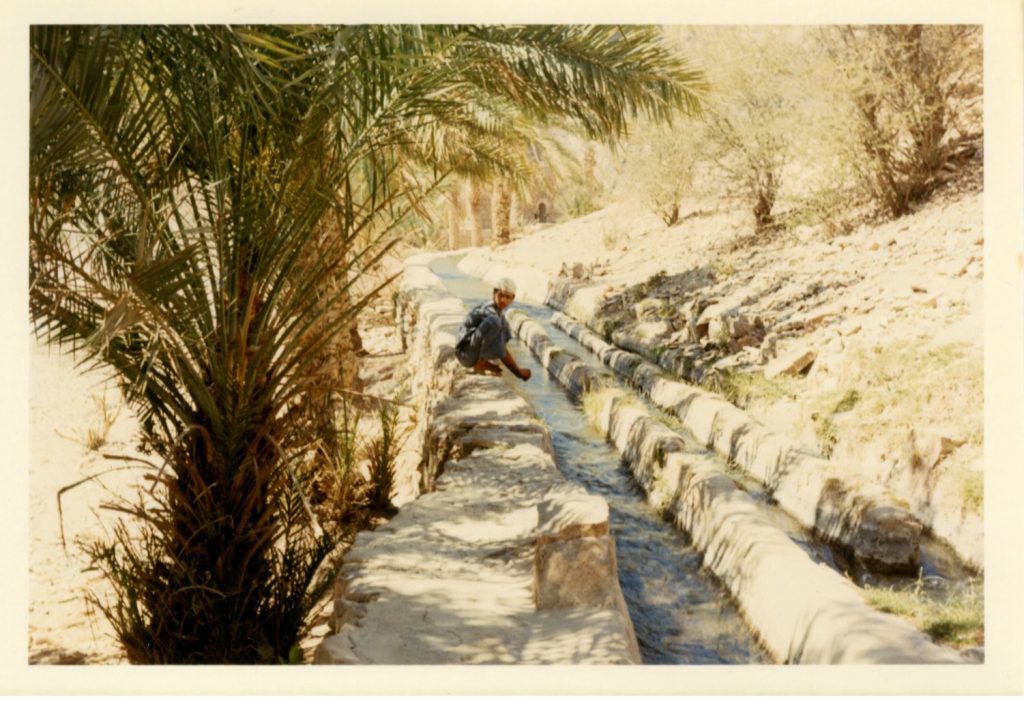

In his notes, Shebbeare describes seeing men cleaning a falaj (an endless talk that has been compared to the proverbial painting of the Forth Road Bridge), as well as some details of their construction, maintenance and ownership. His papers also contain correspondence in English and Arabic relating to a dispute between Seif bin Hamood al Qasimi and the Petroleum Development Oman (PDO) company regarding the reduction of waterflow in the of Falaj al Taibi, – also near Izki – which Seif claimed had been caused by the PDO’s actions in building a pipeline nearby (EUL MS 293/1/). Other papers in the collection relate to a divorce case, offering an insight into the social and marital customs of the region (EUL MS 293/2) within the wider context of village feuds and legal traditions.

Another of Shebbeare’s falaj photos, taken with a camera given to him by Sultan Said bin Taimur

Oman under Sultan Said bin Taimur

Sultan Said bin Taimur (1910-72) had been ruling the country since 1932, when he succeeded his father Taimur bin Faisal as 13th Sultan of Muscat. He inherited a colossal amount of financial debt, owed to Britain and India, as well as a country that was effectively divided into two halves: the cosmopolitan and more secular culture centred on Muscat and the coastal areas, which was controlled by the Sultan, and ‘Oman proper’, the interior region inhabited by tribal groups who were headed by an Imam, the religious leader of the Ibadi sect of Islam. The latter is described in detail in The Imamate Tradition of Oman (Cambridge University Press, 1987) by John C. Wilkinson, whose papers are also held here at Exeter and will be the next collection to be catalogued: watch this space for another blogpost!

Over his 37 year rule Said bin Taimur succeeded in bringing his country out of debt, due in part to the discovery of oil. Extracting this was not easy as the wells lay in areas controlled by the tribes, and tension over the intrusion by oil workers led to violent clashes and a series of armed conflicts between the Sultan’s forces and the tribes. The Imamate finally came to an end in 1959, but this was achieved only through military support from Britain. The Sultan moved his residence 800 km away from Muscat to Salalah, and became increasingly reclusive, refusing to leave his palace and accessible only by appointment or through wireless contact shared with a select few. His determination to avoid returning to debt resulted in decades of financial parsimony, with hardly any investment in infrastructure or technology, an almost complete absence of education, and an isolated, anachronistic society that was described by outsiders as ‘medieval’. Discontent and unrest had been growing since the mid-1950s, especially in the Dhofar region, and the Sultan was increasingly reliant upon the British government for support.

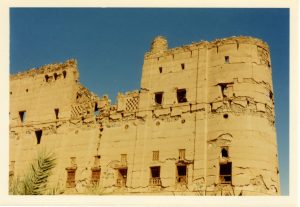

Oman has over 500 castles and forts dotted across its landscape, many of them well-preserved

Suspicious of intrigue among relatives, Said avoided placing significant power in the hands of any senior family members and preferred instead to appoint outsiders – like Shebbeare – to senior positions in his government. Over 60% of the army’s rank and file – and almost all the officers – were British. The post of Minister of Internal Affairs was held by Ahmad bin Ibrahim Al Bu Said from 1939 to 1970, but the Sultan shrewdly limited his power by devolving some of his responsibilities onto Shebbeare, the Governor of Muscat, Shihab bin Faysal, Governor of Al-Sharquiyah, Ahmad bin Muhammad al-Harithi, and Director of Education, Ismail bin Khalil al-Rasasi. Other British officials in the administration included L.B. Hirst, Secretary for Petroleum Affairs, C.J. Pelly, Director of Planning and Development with William Heber-Percy as his secretary. Many of these appointments came in 1967 as oil revenues began to stream in, following the discovery of commercial quantities of oil in 1964.Francis Hughes, Managing Director of Petroleum Development (PDO) wielded more power and influence with the Sultan than many of his senior administrators, to whom Hughes was often asked to pass on official messages.

The Sultan’s distrustful isolationism extended to his treatment of his son Qaboos, who had returned to Oman in 1966 after being educated in England. He was kept under virtual house arrest in his father’s palace, isolated from political activities and contact with government officials except a select few permitted by the Sultan. As Sir William Luce commented in March 1970, the Sultan’s ‘inhuman treatment of his son’ had turned Qaboos into a potential rebel, and his policy of handing all senior posts to British and Indians rather than his own people had made the country ‘ripe for revolution’ (EUL MS 146/1/3/4). Luce (despite accusations made to the contrary) played no part in the forthcoming coup, and his prescient analysis of the situation stemmed from his intimate knowledge of the region and years of experience dealing with Gulf politics and culture.

The Coup of 1970 and Shebbeare’s Departure from Oman

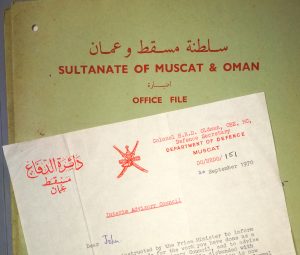

On 23 July 1970 Qaboos forced his father to hand over power in a (relatively) bloodless coup. He was supported in this by the British, including intelligence officer Captain Timothy Landon, who had trained with Qaboos at Sandhurst and had been visiting him in Salalah, and Col. Hugh Oldman, the former commander of Oman’s armed forces who had returned from retirement in February 1970 as Defence Secretary. Said bin Taimur was deposed and sent into exile, spending the last two years of his life in the Dorchester Hotel in London, where he died on 1972. Under Sultan Qaboos the new government was restructured, with most of the British officials – Shebbeare included – losing their posts. Qaboos appointed his uncle, Sayyid Tariq bin Taimur, as Prime Minister of Oman, although such was the extent of the isolation imposed by his father, the two men had never met before. During his preparatory work for the founding of the UAE, Sir William Luce met with Sayyid Tariq bin Taimur at the Bustan Hotel in Dubai on 7 September 1970. He recorded their conversation in detail, and later wrote up a report entitled Thoughts on Oman in which he quotes Tariq as saying: ‘we will keep Oldman, but there are some British officials we do not need’ [EUL MS 146/1/3/7]. Hugh Oldman was indeed one of the few who was kept on, and among the papers in the archive is a letter from him to Shebbeare, dated 20 September 1970, confirming the dissolution of the Interim Advisory Council of which he had been a member. (This had been set up to fill the vacuum created by the departure of the old sultan.)

Letter from Hugh Oldman to John Shebbeare (EUL MS 293/1)

After spending a few months visiting friends in Pakistan, Shebbeare returned to Oman and embarked on a series of travels around the country, walking alone in the mountains as well as exploring regions he had not visited while employed by the sultan. He records these travels in fifty pages of hand-written notes that were used in preparation for a lecture about Oman he gave in the mid-1970s.

Photograph by John Shebbeare

Under Qaboos, Oman embarked on a process of modernization and reform, which included huge advances in education, healthcare and technology. The country’s name changed from ‘Muscat and Oman’ to simply ‘Oman’, and with Sultan Said’s isolationism reversed, friendly contacts were established with other countries in what has proved over time to be a remarkably flexible and well-balanced approach to foreign relations.

Meanwhile, after returning to the UK, Shebbeare became a teacher at Little Hampden Manor School before eventually retiring to East Leigh House in the village of Coldridge near Crediton, in Devon. He retained links with Oman through membership of the Anglo-Omani Society and was also active in local history, being chairman of the Okehampton History Society for many years, attending meetings of the Crediton Area History and Museum Society, and acting as churchwarden and bellringer of St Matthew’s Church, Coldridge. He died in October 2004.

Studying Oman

The next few years are going to be an exciting time for anyone wishing to pursue research into Oman, for a number of reasons:

Sultan Qaboos, now 78, is still the Sultan of Oman, and after 49 years on the throne he is the Arab world’s longest-serving leader. He has no children, and on 3 March 2017 Qaboos issued a royal decree appointing his cousin Sayyid Asaad bin Tariq Al Said as deputy prime minister for international cooperation and the sultan’s special representative – an announcement that was widely seen as indicating Sayyid as his heir and successor. (Sayyid is the son of the sultan’s uncle, former Primie Minister Tariq bin Taimur.) The long reign of Qaboos has been one of relative stability, and it is unclear what the effect might be of a change of ruler. Some have suggested that the Imamate may re-emerge and there have been reports of ‘Ibadi activists’ in recent years seeking to push such an agenda.

Aware of the need to adapt to a rapidly changing world, Oman produced ‘Vision 2020’ in the late 1990s, laying out an ambitious plan for economic diversification, technical development and social equality. Water supply has become a growing concern because of the massive population growth since 1970, with the future development of commodity extraction, environmental issues and the fossil fuel industry all playing a critical role. It will be interesting to see how much of Vision 2020 is realised.

From an archival perspective, 2021 will be of crucial significance as the government papers of Harold Wilson and Edward Heath relating to Britain’s involvement in Oman are due to be released from embargo and should be available for study. These papers could be profitably augmented with work using Exeter’s archival holdings on Oman, of which the Shebbeare papers form just a small part. The catalogue entries can be found here.

My comments or reference is not related to much of this article . Other than that Mr Shebbeare was my history teacher at LHM . He was always such an interesting man and instilled a love of history and natural history in me.

A true Englishman !