University of Exeter Special Collections is lucky to have a number of enthusiastic and dedicated volunteers. In this blog post our Volunteer Rhiannon McLoughlin talks about her experiences volunteering with the Ronald Duncan Collection.

When I say I work in a library people often respond with “Oh do you like reading?” Whilst I do like reading this doesn’t tend to be part of the job description! However, my time volunteering at Exeter University Special Collections during 2017 in order to gain some insight into the differences between library and archive work did, I am happy to report, involve a lot of reading.

When I found I was to work alongside Project Archivist Caroline Walter on the Ronald Duncan Collection I was intrigued as he is not an author I had come across before. Caroline kindly loaned me the first volume of his autobiography and I enjoyed getting to know this colourful character alongside the work.

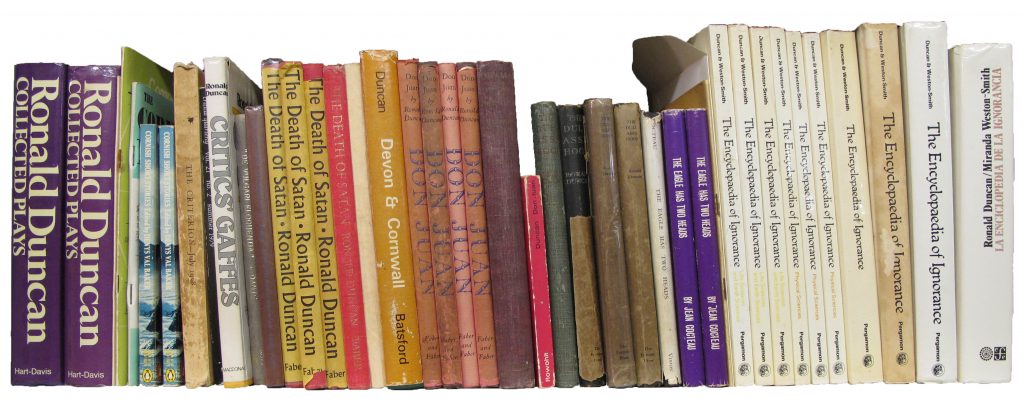

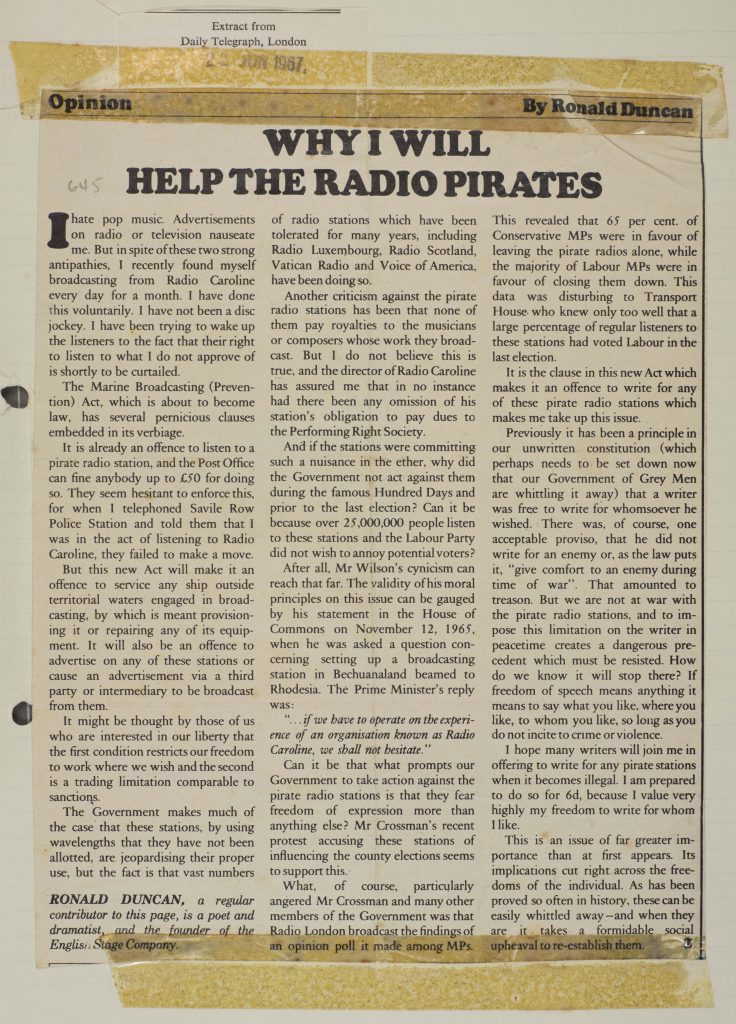

I started out cataloguing the Ronald Duncan book collection. Cataloguing books for an archive is a far slower process than the new library books I normally deal with but can be much more fascinating. I found myself leafing through items looking for anything that made them singular – notes, dedications, markings, edition numbers, or inserts of letters, press cuttings, even a risqué postcard!

I was impressed by the wide variety of writings Duncan produced. Writer, poet, playwright, librettist and editor the collection shows his interests lay in many directions. As a Devonian I particularly enjoyed the local connection and could not help but stop occasionally to read bits and pieces about North Devon life. Whilst his former home and rented buildings may look idyllic now it sounded a far more hardy existence then in wartime and winter months. The tales of pouncing on items washed up on the beach particularly made me chuckle whilst his “Guide to housebuilding and smallholdings” and volume on tobacco farming demonstrated his determination to turn his hand to self-sufficiency.

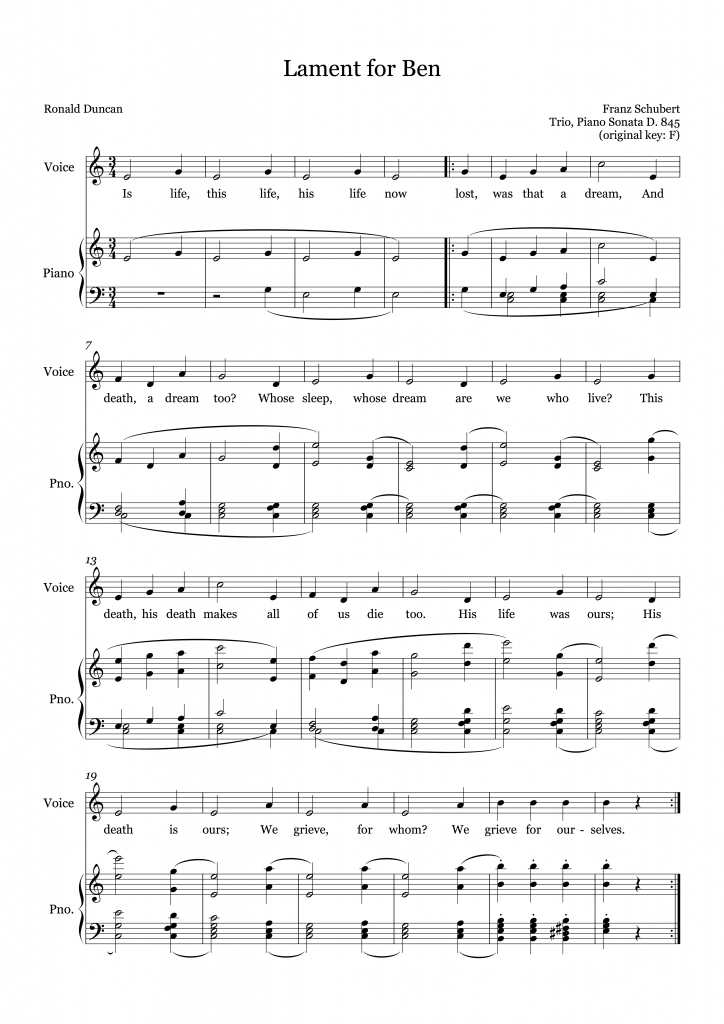

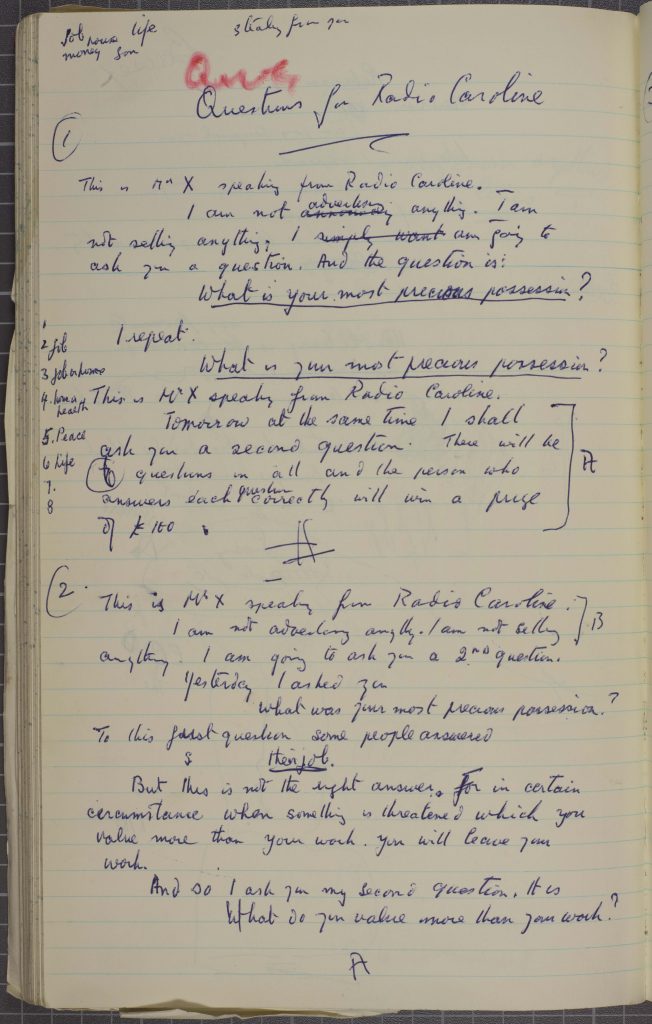

The book collection contains not only his own writing career but writings and responses by others to his work- from letters in journals to student theses about him. There are works in progress, annotated books, proof copies and newsletters pieced together. There are a large number of different literary journals he contributed to and programmes for his plays. There are anthologies where his verse was included – “The site: choose a dry site…” seems a particularly popular choice. There are also items translated into other languages including Polish and Turkish and of course various musical scores and items relating to his work with Benjamin Britten.

I found some of Ronald Duncan’s self-published items by his own Rebel Press to be of especial interest. These are often short limited edition runs such as the volume “Auschwitz” with sobering illustrations and a volume of poems by Virginia Maskell under a pseudonym [Leaves of Silence by Simon Orme].

The book collection indicates the important relationships in Ronald Duncan’s life. Most copies of his own work are signed by him and many are also signed “desk copy” so were clearly his own personal copies – one amusingly “if anywhere else it was stolen”! But many of his books are variously inscribed to friends and family – including a multitude to his wife Rose Marie – usually loving inscriptions but some hinting at more challenging times in their relationship. A particular marker of his friendship with Gandhi are gifts of tiny books of silvery woody paper with Gandhi’s writings – one complete with woodworm holes spiralling throughout.

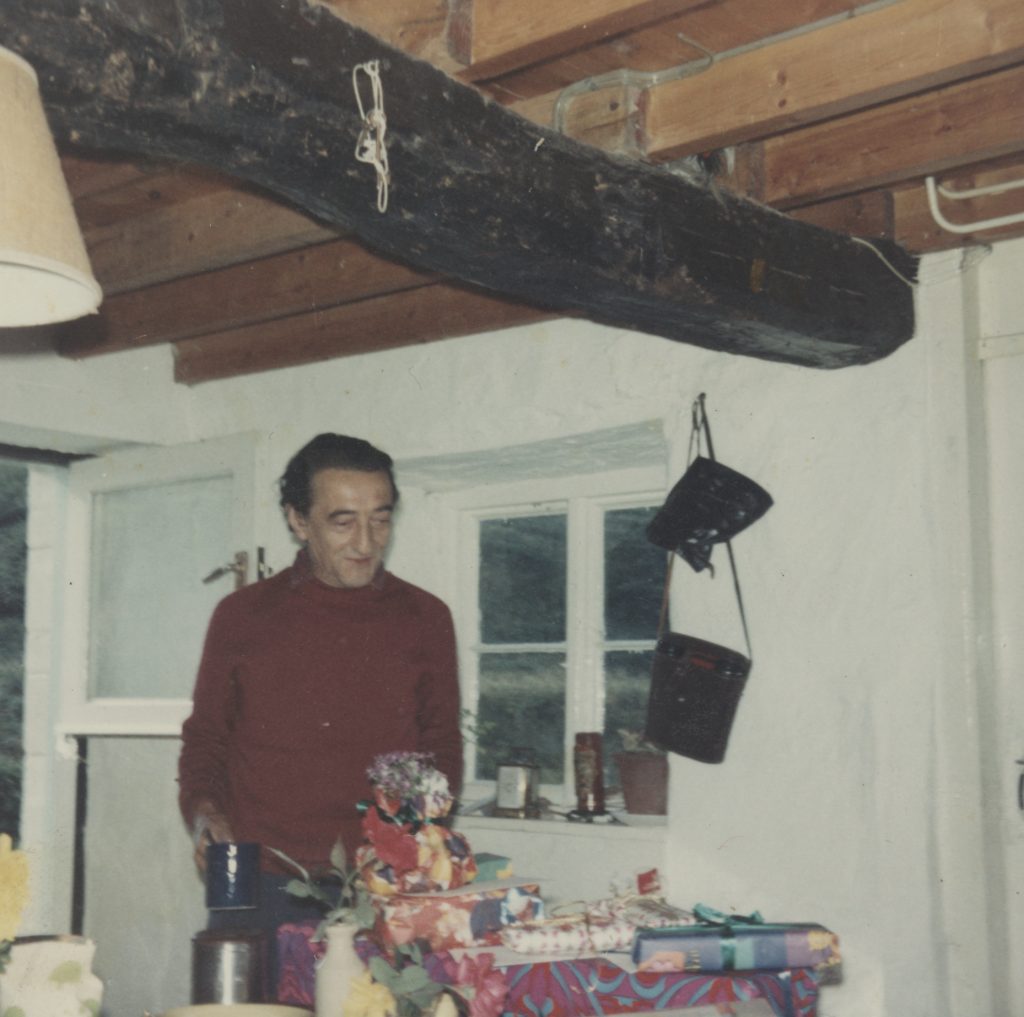

Once I had finished cataloguing the book collection I began to read through some of Rose Marie’s diaries in preparation for digitisation and also to sort photographs into archival wallets. Rose Marie’s diaries are written in a lively and readable style and give a real sense of the challenges of their North Devon lifestyle (including having the band Deep Purple stay in their rental property) and provide a further window onto Ronald Duncan’s work. Repackaging photographs offered pictures of their life I had been getting to know through words – family members, the house, the coast and their beloved horses.

I volunteered to get experience of archival work but found myself equally glad to have gained experience of Ronald Duncan. Working on this collection I got drawn in by the writing and whilst I found myself often having to record that there were signs of damp in the condition note of the books I rather liked the sense that gave of somebody working away at the edge of the sea in his little writer’s hut.