As much of the Kurdish material we hold in the library and archives relates to Kurdistan – the area that covers territories within Iraq (Southern Kurdistan), Iran (Eastern Kurdistan), Syria (Western Kurdistan) and Turkey (Northern Kurdistan) – it is sometimes forgotten that there is a large Kurdish diaspora that lives outwith this region, with historically established communities. In this blogpost I am going to look at the newspaper Rya T’eze, which was the first Kurdish newspaper to be published in Latin script.

The Kurds in Armenia

Most of the Kurds in Armenia originally came from Turkey, beginning to settle in numbers around 1828 to escape from fighting during the Russo-Turkish wars, with migration increasing during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Many of them belonged to the Yezidi community, who follow a religion that fuses elements from Islam and the ancient Persian faith of Zoroastrianism.

Over half of the Kurds in Armenia live in the capital city, Erivan, previously known as Yerevan, or ‘Rewan’ in Kurdish. This city, as will be discussed below, has played a significant role in the development of Kurdish culture.

In 1921 Kurds here began to use a Kurdish alphabet that was derived from Armenian characters; this lasted for about eight years before it was replaced by a Latin alphabet, which was created by a Yezidi Kurd named Arab Shamilov (in Kurdish, Erebê Şemo/Ә’рәб Шамилов or Ereb Shemo), working closely with an Assrian named Isaac Marogulov. Born in 1897 in Kars in eastern Anatolia (NE Turkey), Shemo had fled to Armenia with his family after the First World War. His book Xwe bi Xwe Hînbûna Kurmancî [Teach Yourself Kurmanji], was published in 1928 and was the first Kurdish book to be printed using the new Latin alphabet.

Between 1930 and 1937 there was a flowering of Kurdish education and culture in Armenia, with almost thirty Kurdish schools established, children taught to read and write in Kurdish, and a regular stream of Kurdish-language books published each year. Shemo’s novel Sivane Kurd [The Kurdish Shepherd] came out in 1935, followed by his anthology Folklora Kurmanca. It was against this background that Rya T’eze appeared.

Rya T’eze 1930-1937

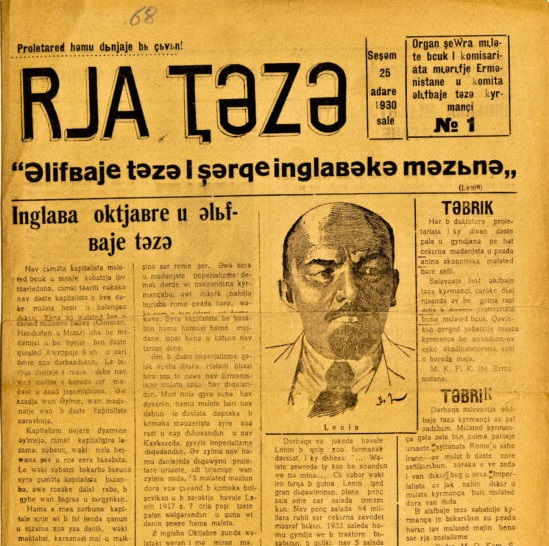

The first issue of Rya T’eze

Рйа Т’әзә or Rya T’eze (sometimes spelled Riya Teze) means ‘New Path’, and the first issue was published on 25 March 1930, printed in Kurmanji Kurdish but using the Latinised alphabet of Shemo-Marogulov. It had four pages and came out twice a week, with a circulation of some 600 copies. Celadet Alî Bedirxan’s magazine Hawar [The Cry] – which began publication in 1932 – acknowledged the importance of Rya T’eze in an article (No.8, 1932), written by Herekol Azizan:

Produced under the auspices of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Armenia, the Supreme Council and the Council of Ministers of the Armenian SSR, Rya T’eze was bound to reflect Soviet ideology, and even though it was written in Kurdish, there is perhaps a disappointingly sparse amount of material on Kurdish culture. At first the newspaper was run by three exiled Armenians who knew Kurdish – Kevork Paris, Hraçya Koçar and literary critic Harûtyûn Mkirtçyan – before Kurdish linguist and author Cerdoy Gênco took over as editor in 1934. That was also the year that the first ever pan-Soviet Congress of Kurdology was held – in Yerevan, naturally – which called for the creation of a Kurdish dictionary and historical grammar. An education academy had already opened in Yerevan with the aim of training Kurdish language teachers.

However, under Stalin’s increasingly tight grip on the Soviet Union there was little place for dissent or devolution, and the resources and freedom open to Kurds in Armenia began to decline. Kurdish-language teaching and publishing were discouraged, and the Cyrillic alphabet was imposed on Kurds to encourage them to learn Russian, Armenian or Georgian (and therefore abandon their own language.) Between 1937 and 1944, Caucasian Kurds were deported to settlements within places such as Uzbekhistan and Kazakhstan in Central Asia, where they faced severe restrictions on freedom of expression and movement. Ereb Shemo was himself among these, and he would not return until 1956. Publication of Rya T’eze was shut down in 1937, and would not resume for almost twenty years.

Rya T’eze 1955-2003

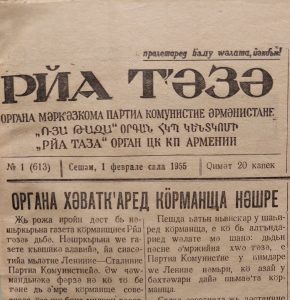

Front page of the revived Rya T’eze, 1 February 1955 – the first issue in our holdings.

Following Stalin’s death in 1953 and the more moderate governance introduced by his successor, Nikita Khruschev, publication of Rya T’eze recommenced in 1955, still in Kurdish but this time printed in a Cyrillic alphabet that had been devised by Heciyê Cindî, another Yezidi Kurd who had worked on Radio Yerevan, and also spent time in exile during the 1940s. Nonetheless, Cindî had managed to complete a doctorate in Kurdish folklore while in exile, and was also the author of a Kurmanji reader and other Kurdish books. The new editor was Mîroyê Esed (1919-2008), who would continue to run the paper until 1989.

This again was another period in which Kurdish culture was able to flourish in Armenia, and the local radio station also began broadcasting in Kurdish in January 1955. Gayané Ghazaryan has written a fascinating blogpost about Kurds in Armenia and the work of Casimê Celîl (who wrote Kurdish poetry for Rya T’eze) and his family for Radio Yerevan that can be read here.

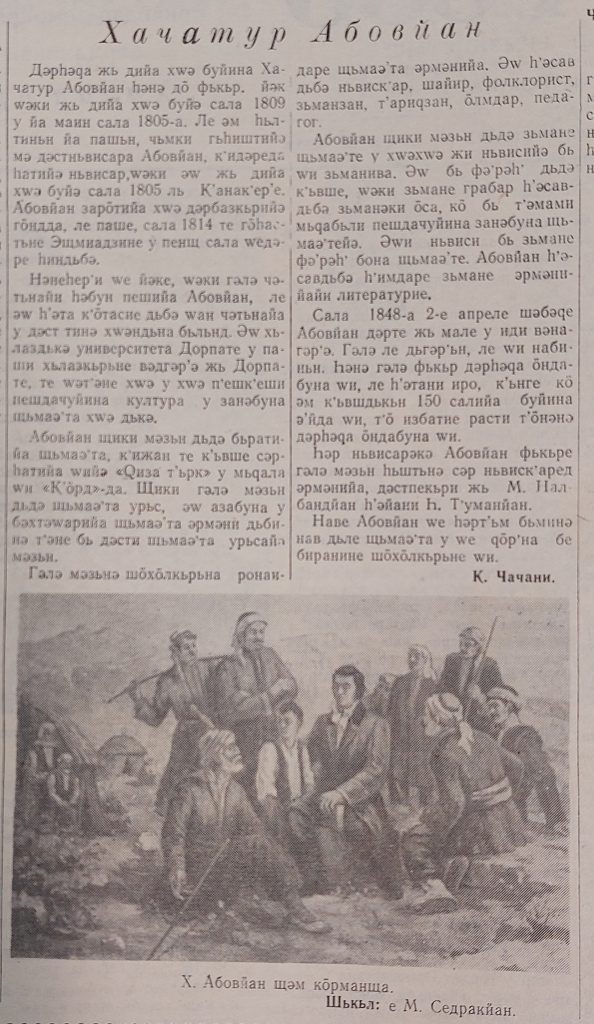

Other Kurdish authors who contributed to Rya T’eze after its relaunch in 1955 included Qaçaxê Mirad, Şekroyê Xudo, Xelîlê Çaçan, Babayê Keleş, Têmûrê Xelîl, Tîtal Mûradov, Egîtê Xudo, Eliyê Ebdilrehman, Hesenê Qeşeng, Pirîskê Mihoyî, Rizganê Cango, Porsora Sebrî, Tîtalê Efo, Karlênê Çaçanî, Şerefê Eşir, Egîtê Abasî, Paşayê Erfût, Letîfê Emer and Gayanê Hovhannîsyan. As before, much of the paper’s content reflected the dominant focus of the Armenian SSR on Soviet politics and history, agricultural and factory production, and so on, but there continued to be articles, poems and other material of Kurdish interest, such as this article from 9 October 1955 p.1 on the Armenian poet Хачатур Абовйан (Khachatur Abovyan, 1809-48), who was a pioneer in the study of Kurdish language and folklore, writing extensively about the Kurds and recording many of their local legends and folk tales. Abovyan laid the foundations for the development of Kurdish studies in Russia.

The article reproduces the famous painting of ‘Abovian Among the Kurds’ by Mkrtich Sedrakyan.

During the 1970s, circulation figures rose from around 2,800 to 5,000 copies, although by the mid-1980s this had dropped back to about 4,000, with occasional changes in the frequency of publication. The death of Erebê Şemo in May 1978 was not overlooked, with a substantial article published on 5 June:

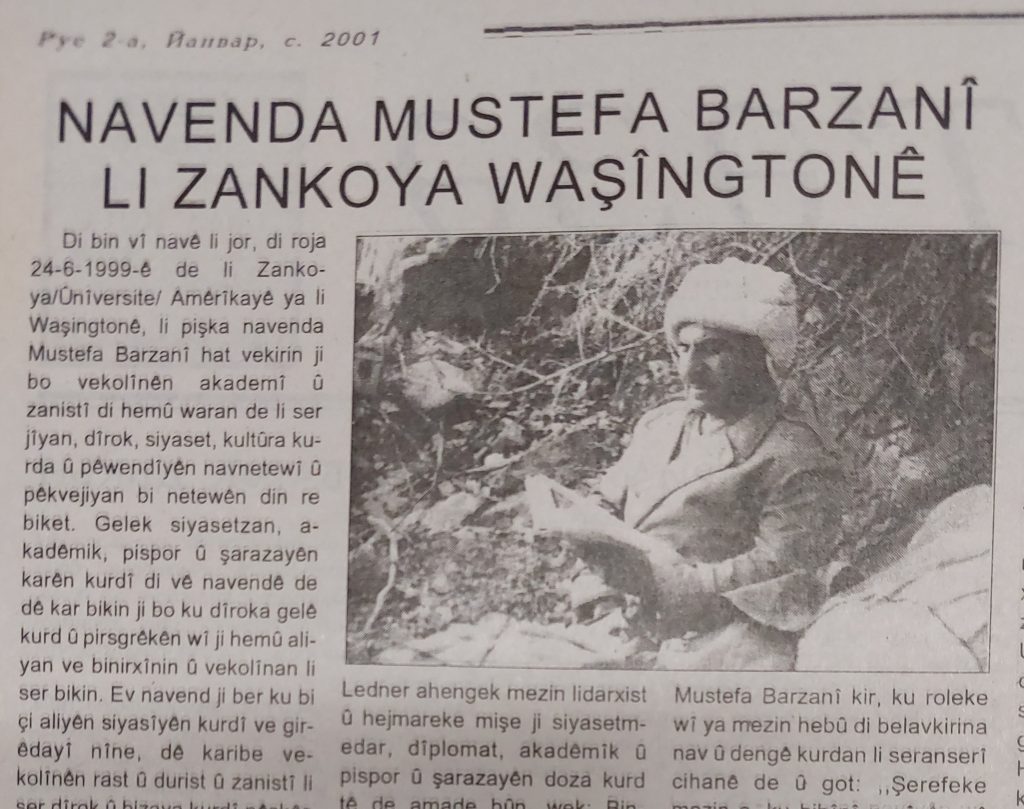

The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1989 placed serious financial pressures on the newspaper, which had been funded by the Armenian SSR and relied heavily on the support of the state. Tîtalê Efo took over as editor from Esed that year, only to be succeeded in 1991 by Emerîkê Serdar, who ran the paper until he was forced to resign due to illness. During this time, the alphabet reverted to Latin in 2001, and the newspaper became a monthly publication with a print run of 500 copies in an effort to reduce production costs.

One positive outcome from the collapse of the Soviet Union was that Rya T’eze began to focus more on matters of general Kurdish interest, rather than adhering closely to the programme of the Armenian SSR. This was probably due in part to the growing reliance of the newspaper on the wider Kurdish diaspora for financial support, but these years saw regular coverage of events in Iraqi Kurdistan.

An article on Kurdish leader Mustafa Barzani from 2001, showing the newspaper’s return to Latin characters and improved coverage on matters of Kurdish interest outside Armenia

However, despite the efforts of the editor and Kurdish donors to keep the newspaper afloat – including an injection of money, the assistance of Kurdish volunteers and support from organisations such as the Lalish Foundation – it was clear that production was no longer financially viable. Publication wound down at the end of 2003, and after a few sporadic issues over the next two years, the press finally closed with No. 4818 in October 2006, which included a review of Dr. Khanna Omarkhali’s book on the Yezidis, Йезидизм (2005) and a tribute to Kurdish writer Emînê Evdal (1906-64), another Yezidi contributor to Rya T’eze during the 1930s and a pioneer in Kurdish language instruction.

Rya T’eze remains a remarkable record of the Kurdish community in Armenia, and is also of particular interest to scholars researching the history of the Yezidis and their culture. Our holdings of the newspaper are probably the most extensive outside the former Soviet Union, and this is a fantastic resource for postgraduate study, either from our own Centre for Kurdish Studies or further afield. Enquiries about access to the newspaper should be directed to Special Collections.