‘I have never met a journalist who isn’t biased about practically anything and, since they aren’t Daleks, this probably shows through in their copy. The idea that a journalist should be unbiased is a curious one. The best ones are very biased indeed.’

– Terry Pratchett, reviewing Publish it Not… The Middle East Cover-Up (London: Longman, 1975) by Michael Adams and Christopher Mayhew MP in The Bath and West Evening Chronicle, 30 August 1975. (EUL MS 241/5/2)

Michael Adams’ career as a journalist spanned almost six decades, during which he established a reputation not only as an expert on the Middle East but also a passionate campaigner on behalf of the Palestinian people living in the Israeli-occupied territories. He was well aware of the potential conflict between these two aspects of his work and his papers offer valuable insights into the internal and external workings of the media. How does a journalist balance personal beliefs against the need to present an equivocal view of events for his audience? How do newspapers and broadcasters balance their desire for editorial independence with their reliance on financial sponsorship and advertisers with their own agendas and vested interests? How can we learn to navigate the complex relationship between media representation, human experience and political reality?

These are issues with which Adams had to wrestle over many years, and which cost him a great deal of personal pain and sacrifice. Like many critics of Israeli policy, he was accused of anti-Semitism and became embroiled in an unpleasant lawsuit trying to defend himself. During a period when sympathy in the UK lay almost entirely in favour with Israel and in opposition to its Arab neighbours, Adam’s reporting upset many and strained his relationship with his editor at The Guardian, Alastair Hetherington. How these events and tensions played out over the years is documented in detail, through correspondence from different parties, personal notes, typed reports and presscuttings.

Although Adams’ name is closely associated with the subject of Israel-Palestine relations, he travelled widely through the Arab world and wrote about many other regions during his long career

Born in Addis Ababa, Adams was educated at Sedbergh School before going up to Oxford, although his time at university was interrupted by wartime service in the RAF. He was shot down and captured in 1940 and spent most of the war in Luchenwald POW camp near Berlin; we have two early typescripts – Solitude and Adventures with Robert Browning – about his experiences as a POW, written in Oxford just after the war (EUL MS 241/5/1). Having obtained his MA in 1948, Adams began working as a BBC scriptwriter, and travelled in Greece, Turkey and American before his appointment as Middle East correspondent for The Guardian in 1956. As Adams admitted in the introduction to his first book, Suez and After (Boston: Beacon Press, 1958): ‘No one could report events in the Middle East for long without becoming to some extent involved in them. Where principles are in conflict, and prejudices heartfelt, only a saint or a cynic could retain his detachment, and I am neither.’

His involvement in these events was deepened in 1967 after the BBC sent him to make a series of radio programmes gauging what Arabs thought and felt about the situation after the Six-Day War. This work took him through the occupied territories of Gaza, Jerusalem and the West Bank, and while his meetings with Palestinian people inspired his book Chaos or rebirth: the Arab outlook (London: British Broadcasting Corporation, 1968), the visit had a profound effect on his own views. Disturbed not only by the brutal treatment of Palestinian families that he witnessed, but also by the failure of British and American media to report on these matters, he committed himself fully to addressing what he perceived to be a biased misrepresentation of the situation in the Middle East.

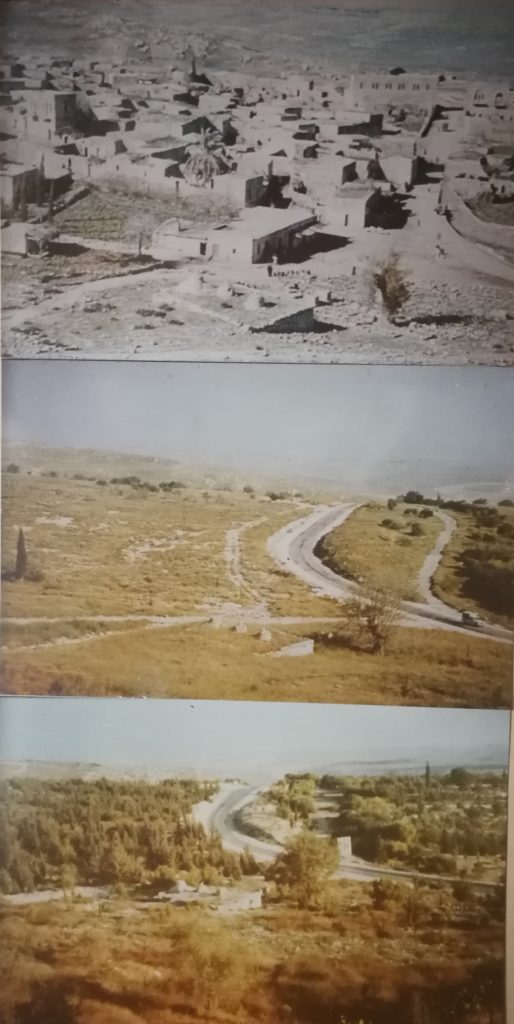

Three photographs of Imwas (Emmaus), taken in (top to bottom) 1948, 1958 and 1968.

EUL MS 241/5/3

One of the events that moved him deeply at this time was the Israeli demolition of three villages (including Imwas, long identified as the biblical ‘Emmaus’) between Jerusalem and Ramla. We have an entire file documenting Adams’ research into the destruction of Imwas, including photographs, maps and letters from former residents of the village (EUL MS 241/5/3). Adams’ persistence in publicising these events led to further difficulties with his editor at The Guardian, who refused to publish the article – it appeared instead in The Sunday Times.

CAABU

In 1967 Adams was one of the co-founders of the Council for the Advancement of Arab-British Understanding (CAABU), which aimed at countering some of the widespread ignorance and prejudice about the Arab World. Among Adams’ papers are some of the original documents relating to the founding of CAABU as well as records of some of the meetings, events, lectures and exhibitions organised during its early years. (EUL MS 241/3) Adams found another platform for his mission to promote a greater understanding of the Arab world when he became the first editor of the magazine Middle East International (MEI) in 1971. The archive holds copies of many of his MEI editorials and articles.

Remaining frustrated by the difficulties faced by those who wished to publish opinions that might be deemed critical of Zionism and favourable to the Arab states, Adams teamed up with Christopher Mayhew, a Labour MP and Foreign Office official, to write Publish it Not… The Middle East Cover-Up (London: Longman, 1975) which presented evidence of systematic media bias in western coverage of matters relating to Israel and Palestine. The book also offered some practical solutions for the future of the peace process – something that Adams continued to think about and actively seek for the rest of his life.

Black September

Perhaps the most striking instance of Adams’ direct involvement in Middle Eastern affairs was the role he played in negotiating the release of hostages following the hijacking of five passenger jets during the Jordanian civil war of September 1970 – a period of bloody warfare known as ‘Black September’ when the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) and the more radical Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) tried to wrestle control of Jordan out of the hands of King Hussein and give greater autonomy of the majority Palestinian population. The hijackings were carried out by the PFLP almost simultaneously, and after one plane was surrendered in London and other blown up in Cairo, the remaining three were flown to Dawsons Field, an airstrip near Zarka in Jordan. Most of the passengers were released, but around fifty Israelis and Americans were detained. Given the chaotic situation and the lack of trust on all sides, negotiations for the release of the hostages proved difficult and Adams flew out to help on behalf of CAABU.

He landed in Amman, the capital of Jordan, where he met Walid Khaled, brother of the imprisoned hijacker Leila Khaled. Subsequent events are recorded in a 52-page diary transcript, which details his meetings with representatives of the PFLP, Jordanian military and British and Dutch ambassadors, as well as the escalating fighting in Amman, the destruction of the planes and the release of various Arab prisoners from European jails – including Leila Khaled – in exchange for the hostages (EUL MS 241/2/1). In addition to Adams’ account there are copies of various communications between the Foreign Office, the UK Ambassador to Jordan and other officials involved in the negotiations (EUL MS 241/2/2).

Some of Adams’ correspondence, including images of Bethlehem sent as Christmas greetings. EUL MS 241/2/5

Any assessment of Adams’ achievements as a journalist and campaigner must rest primarily upon the quality of his research and writing, and our collections contains copies of scores of his articles in both typescript and published versions, in addition to his working notes, diaries, photographs, maps and letters. The collections would be well worth exploring for anyone seeking to understand better the recent history of the Middle East – in particular, the relationship between Israel and Palestine – as well as the role and responsibilities of the media in educating the public and influencing political opinion. The online catalogue can be explored here.