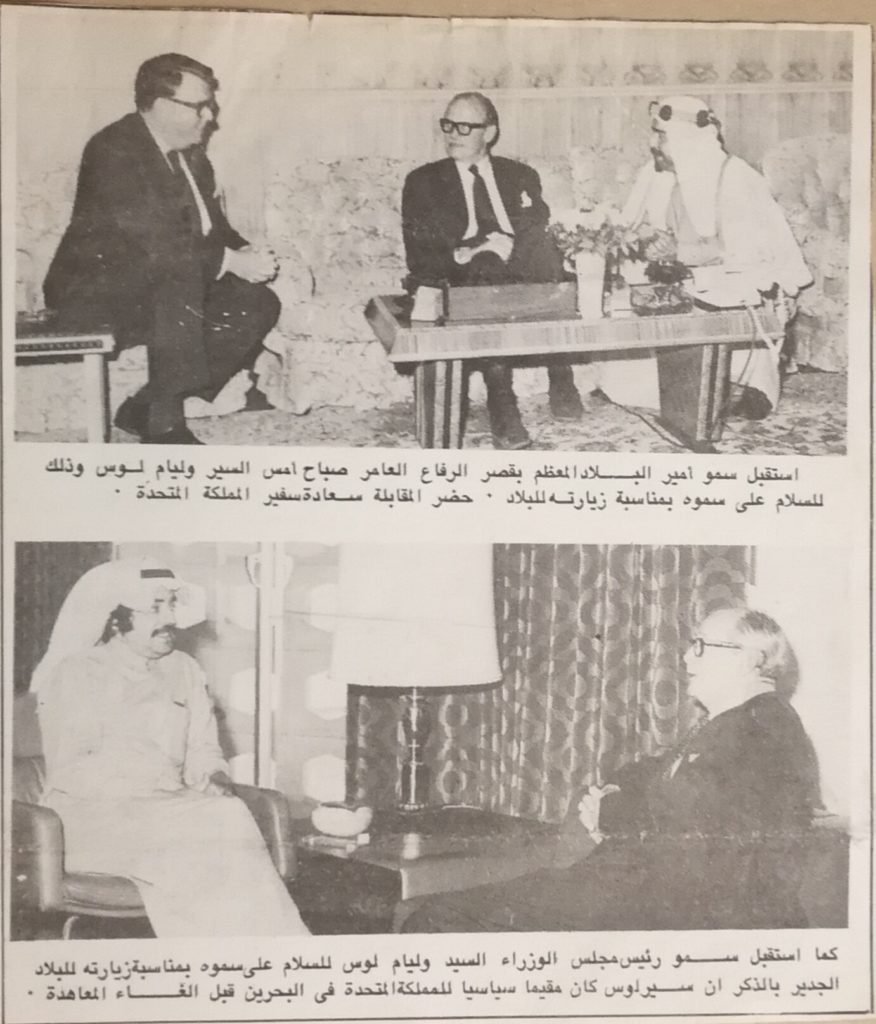

The personal face of diplomacy – Sir William Luce meeting Sheikh Isa of Bahrain in 1977. EUL MS 146/1/4/7

While at Exeter University Glencairn Balfour Paul, one of the founders of the Centre for Arab Gulf Studies (later the Institute of Arabic and Islamic Studies), wrote The End of Empire in the Middle East: Britain’s Relinquishment of Power in Her Last Three Arab Dependencies (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991) in which he paid the following tribute to Sir William Luce’s work as the Foreign Secretary’s Special Representative for Gulf Affairs:

Luce had to deal with the vain and arrogant Pahlavi government in Iran, with suspicious Saudis and anxious Gulf Rulers, not to mention his political bosses in London, some of whom were far from committed to the decision to terminate the British protective presence in the Gulf. He charmed everybody, he persuaded everybody, he was patient, good-humoured (with occasional explosions) and skilful. (xviii)

Some sense of Luce’s personality – and how important it was for his diplomatic work – can be gleaned from the collection of his working papers that are held in our Middle East Archives and have recently been catalogued. Material relating to his earlier career with the Sudan Political Service (1930-55) is held at the University of Durham, while the papers here in Exeter cover the period between his arrival in Aden in 1956 and his final visit to the Gulf States in 1977 shortly before his death.

Following posts as Governor and Commander-in-Chief of Aden (1956-60) and Political Resident in the Persian Gulf (1961-66), he was called back out of retirement in 1970 to act as Personal Representative of the Foreign and Commonwealth Secretary – Sir Alec Douglas-Home – overseeing the arrangements for British withdrawal from the Gulf. His task here was to ensure ongoing stability and the continuation of good relations with the various Arab leaders in the region – he played a vital role in the establishment of Kuwait, Bahrain and Qatar as independent states, as well as the foundation of the United Arab Emirates.

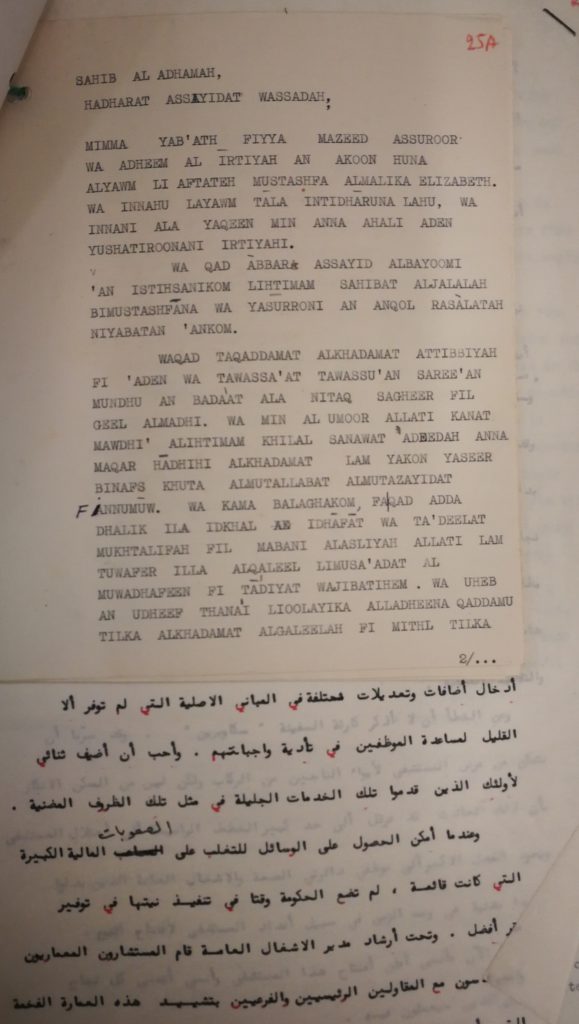

Text of Luce’s speech at the opening of the Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Aden, 28 April 1958. Luce had become a confident speaker of Arabic while in the Sudan, but when giving speeches in Arabic he wrote the text out in phonetic script which he evidently found easier to read. EUL MS 146/1/1/5

Luce’s success in these complex and delicate negotiations was due largely to the personal relationships he had forged over the years, earning the trust and affection of Gulf leaders during a time of great political tension and mutual suspicion. Although the papers held in our collections relate almost entirely to his official activities, they reveal the extent to which diplomatic relations between the Gulf states relied upon human contact between individuals and Luce’s own personal skills and charm. So what can do the archives reveal?

The Luce Papers: personal or political?

The papers held here are a diverse group and include handwritten and typed correspondence, political memoranda, official reports, notebooks and appointment diaries, speeches, presscuttings, offprints and printed works such as pamphlets and journals. Some of the papers were written by Luce for his own use, or to be shared privately with close friends or colleagues, and retain an intimate, informal tone. (It should also be noted here that a large collection of personal papers and correspondence remains in the family’s possession.)

Notes written on cigarette paper during his Gulf visit in January-February 1970 reveal the spontaneous and informal aspects of Luce’s work, as well as reminding us that the concept of ‘winning hearts and minds’ in the Middle East has a long tradition. EUL MS 146/1/3/5

Others were intended for much wider platforms, such as public meetings or print media, and are phrased and framed with this in mind. The fact that these items are in the archive itself indicates a personal choice – that at some point Luce made a decision to keep a particular paper or booklet in his possession. There is a need to be aware not only of the material that is not in the archive – i.e. that related papers might have been discarded, lost or simply rejected for preservation – but also that other material may exist elsewhere in other collections that may complement or contradict the picture presented here. Each of the parties that attended meetings with Luce may well have recorded their own version of events, so that even an official government report must be treated as offering only a subjective and partial view of the topic – something especially pertinent for anyone approaching the complex kaleidoscope of Middle Eastern politics.

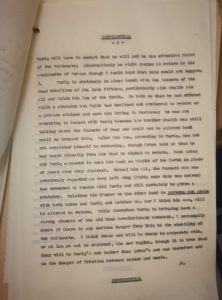

Excerpt from Luce’s confidential report on a meeting he had in Dubai in 1970 with Sayyid Tariq, Prime Minister of Oman. EUL MS 146/1/3/7

The above typed report is from a document entitled Thoughts on Oman and reflects upon conversations Luce had with Sayyid Tariq, Prime Minister of Oman, following the very recent bloodless coup in which Said bin Taimur, the sultan of Muscat and Oman, was replaced by his son Qabus bin Said Al Said. It illustrates the extent to which the wielding of power in the region was part of a tapestry of political allegiances, personal relationships, family history and ancestral relations. Luce’s ability to navigate his way through these complexities relied upon the detailed knowledge he had acquired over the years. The document shows how Luce drew on private discussions in order to advice the Foreign Office on points of strategy.

Personal Representative

Luce had reached the Sudan Political Service’s voluntary retirement age of 48 in 1955 but made it clear to the Foreign Office that he had no intention of ceasing to work. Even after his retirement from the Gulf in 1966 he maintained an active interest in the Middle East, appearing regularly at conferences and discussion groups to make his views known, and writing articles for publications such as Round Table. We have many of these talks and articles in the archive (EUL MS 146/5) as well as related correspondence that reveals the high esteem in which he has regarded within both political and academic circles.

Meanwhile the economic pressures upon Harold Wilson’s Labour administration had forced a reconsideration of foreign policy. In July 1967 Defence Secretary Denis Healey announced that Britain would withdraw its forces from the Gulf within ten years. The following January Wilson announced that this would be carried out by the end of 1971.

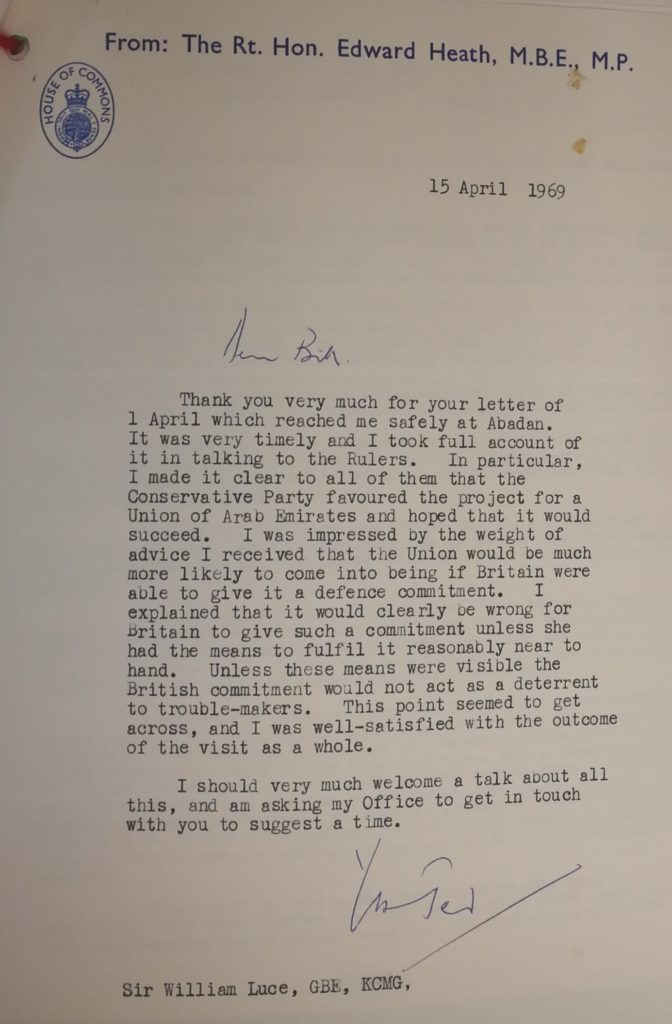

Luce strongly opposed this decision, regarding the announcement of any timetables as detrimental to the government’s position for negotiating terms of withdrawal – a position he had made clear as early as 1966 (EUL MS 146/1/2/2). The Conservative Party opposed Labour’s move in principle and let it be known that they would reverse the policy if re-elected. Following the election of Edward Heath as Conservative Prime Minister in June 1970, Luce was appointed personal representative to the foreign secretary, Sir Alec Douglas-Home, on 27 July 1970. Heath and Luce had almost met the previous year during a tour of the Middle East undertaken by Luce between February and April 1969 in his capacity as a non-executive director of shipping agents Gray Mackenzie & Co., while the then Conservative Party leader was also visiting the region. While Luce thought any attempt to reverse the withdrawal would be unwise, Heath chose to leave that option open, at least in public.

Letter from Edward Heath to Luce, responding to a communication sent to the Conservative Party leader while he was at Abadan in Iran. EUL MS 146/1/2/14

How Luce worked to steer Heath’s cabinet in the right direction is the subject of a large chunk of the archive, which relates to his activities as ‘Personal Representative for Gulf Affairs’ between July 1970 and 1971. He made five major tours of the Gulf during this time, holding meetings with (among many others) the Shah of Iran, King Faisal of Saudi Arabia, Mohammed Fayek, Minister of State for Foreign Affairs in the United Arab Republic, various parties at the Arab League Headquarters in Cairo, Abdul Hussein Jamali, Iraqi Minister of Foreign Affairs, the Prime Minister of Iran, Sayyid Mehdi Tajir (principal adviser to Shaikh Rashid of the UAR), the Amir of Kuwait, the Sultan of Muscat, the rulers of Umm al-Quwain, Ras-al-Khaimah, Ajman and Sharjah, Shaikh Ahmed bin Ali al Thani, Emir of Qatar, and his cousin Shaikh Khalifa bin Hamed al Thani, and the Emir of Bahrain, Shaikh Isa bin Sulman. Each trip is documented by a mass of papers, including draft itineraries, guest lists, arrangements for travel and accommodation, as well as detailed records of conversations, confidential reports based on these conversations, and official government papers showing how this material was then interpreted and communicated for parliamentary debate or cabinet-level discussions. These papers reveal how Luce shuttled from place to place, carefully observing matters of precedence and etiquette in the frequency and sequence of his visits to successive rulers to avoid offence, painstakingly building up agreements and negotiating points in every successive meeting. Early on he had realised that the future of the Gulf Region after the British had left depended upon solidarity between the various Arab leaders, and with that in mind he set about laying the ground for a federation of the nine sheikdoms around the Gulf peninsula. Although he was unable to unite all nine of them – Bahrain and Qatar declared themselves independent states in August and September 1971 – he managed to bring together Abu Dhabi, Dubai, Ajman, Sharjah, Umm Al Quwain and Fujairah to form the United Arab Emirates. The remaining state, Ras Al Khaimah joined the UAE the following year.

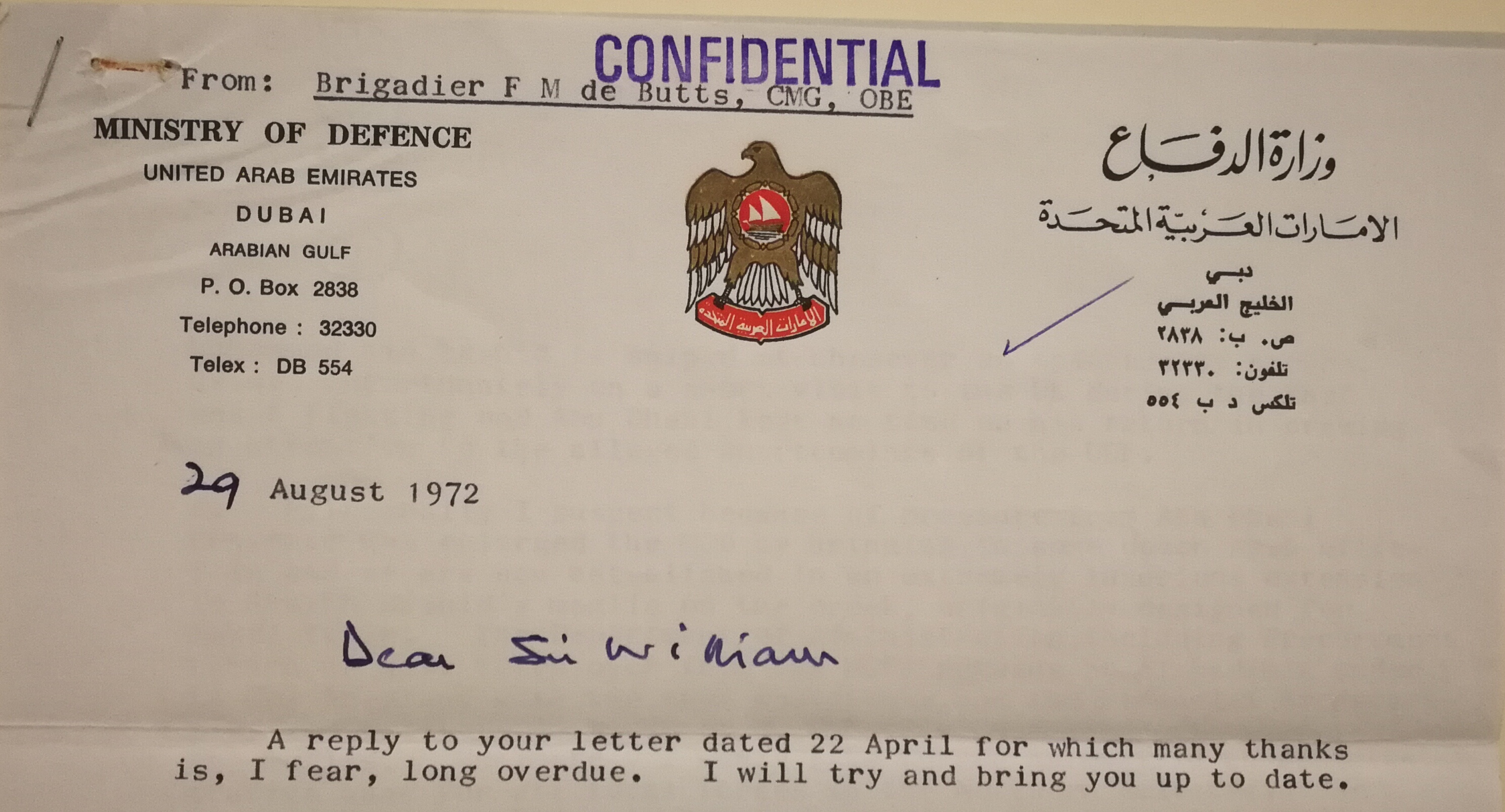

Headed letter from Brigadier F.M. De Butts of the United Arab Emirates Ministry of Defence, to Luce, dated 29 August 1972, and providing an update on various military and security issues. EUL MS 146/1/4/1

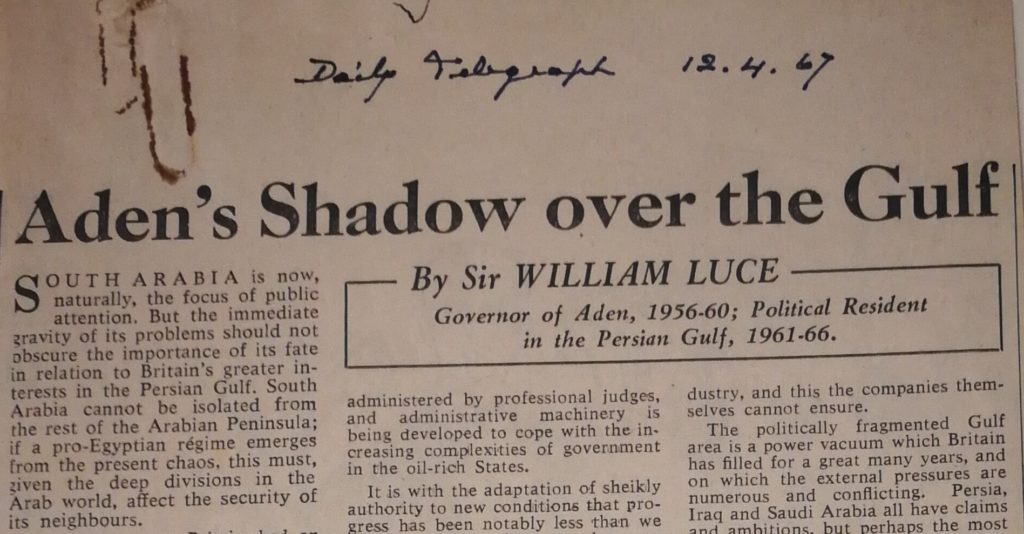

Luce was strongly realistic and pragmatic in his approach to Britain’s involvement in the Persian Gulf and was under no illusions about the historic and political reasons for their presence. Writing in the Daily Telegraph he admitted: ‘It is important today to remember that these Gulf agreements were made on British initiative and primarily to serve British interests. We did not undertake the ‘policing’ of the Gulf for some vague, altruistic purpose; we went there, and remained there, because it has suited us to do so.’

William Luce, ‘Aden’s Shadow over the Gulf’, Daily Telegraph, 12 April 1967. EUL MS 146/1/2/10

Although there is not space to discuss this here, studying the archival records of Luce’s career provide evidence of how his work in the Gulf was shaped by his earlier experiences in the Sudan and Aden. The range of documentation held in the Luce archive provides a fascinating resource with which to explore the wide range of factors that determine how political strategies are both formulated and implemented. While much attention continues to be given to famous and infamous figures in the early history of the British Empire, there is perhaps a need to start focussing more closely on those who played a prominent role in its final stages. The papers of Sir William Luce could provide a bridge for researchers between the contemporary political landscape in the Middle East and its historical roots in the imperial past, as well as illustrating just how much the personal and the political elements of diplomatic life connect and overlap.

Further Reading

Glen Balfour-Paul, The End of Empire in the Middle East: Britain’s Relinquishment of Power in Her Last Three Arab Dependencies.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991

M.W. Daly, The last of the great proconsuls. The biography of Sir William Luce.

San Diego, CA : Nathan Berg, 2014

Luce, Margaret. From Aden to the Gulf: personal diaries, 1956-1966.

Salisbury : Michael Russell, 1987